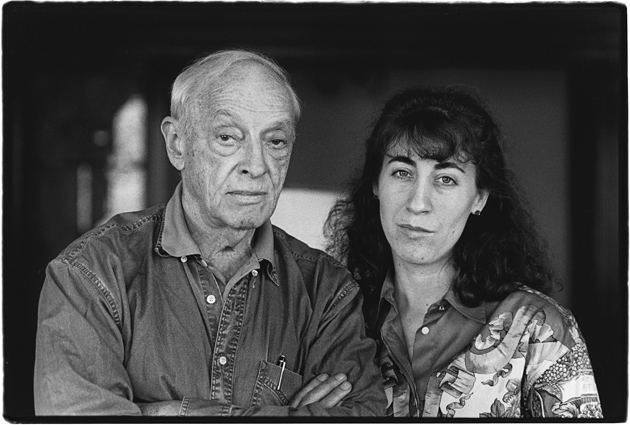

Judith Aronson

Saul Bellow and Janis Bellow, Boston, Massachusetts, 1994; photograph by Judith Aronson, whose portraits of writers and artists have been collected in her book Likenesses: With the Sitters Writing About One Another, published in 2010 by Lintott Press in association with Carcanet Press, UK

The following, the first part of a two-part series, is excerpted from a talk originally given by Saul Bellow in 1988 and now published here for the first time. Footnotes have been added by the editors.

A few preliminary words on the title of this talk: it deals with aspects of my personal history and with the substantiality of the person behind this history. The idea of a substantial person has been subjected by modernist, postmodernist, and postpostmodernist thinkers to tests which make one think of the rude use of effigies by engineers who simulate car collisions and plane crashes—dummies are dismembered before our eyes or devoured by floods of ignited aviation fuel.

The “identity problem” has vexed and plagued the modern intellect. So what business have I, in view of the “new look” for individuals (in a word, for each and every one of us) sponsored by highly influential existentialist, deconstructionist, and nihilist designers, to speak of my personality and my personal history? And the truth is that no such right can be formally defended by a writer—a novelist—who, in any case, would have neither the time nor the metaphysical competency to do the job. All I have to say is that the learned philosophers and critics have raised some questions which perhaps do not have to be raised, sinister questions which I associate with an even more sinister challenge, the challenge, namely, to one’s right to exist in any form.

The philosopher Morris R. Cohen was once asked by a student, “Professor, how do I know that I exist?”

“So?” Cohen replied. “And who is esking?”

Thanks to Professor Cohen I feel that I stand on firmer ground, and can do what I have done all my life: i.e., to fall back instinctively on my first consciousness, which has always seemed to me to be most real and easily accessible. For people who have no access to any such core consciousness, no mysteries exist. Linguistic analysts aim to clear away all mysteries—alleged mysteries, they would say. Facts, however, must be respected, and the fact is that for reasons I can’t explain, my own first consciousness has had a long unbroken history. I wouldn’t know how to defend my faithful attachment to it. All I can say is that it is a fact and I wonder why anyone should feel it necessary to put its reality in doubt. But our meddling mental world puts all such realities in doubt. This world of truly modern, educated, advanced consciousness suspects the core consciousness that I take to be a fact of being inauthentic and probably delusive.

I will ask you for the present to believe that I am right and that what I call the meddling mental world is wrong.

So, in my first consciousness, I was, among other things, a Jew, the child of Jewish immigrants. At home our parents spoke Russian to each other, we children spoke Yiddish with them, and we spoke English with one another. At the age of four we began to read the Old Testament in Hebrew, we observed Jewish customs, some of them superstitions, and we recited prayers and blessings all day long. Because I had to memorize most of Genesis, my first consciousness was that of a cosmos, and in that cosmos I was a Jew. I suppose it would be proper to apply the word “archaic” to such a representation of the world as I had—archaic, prehistoric. This was my “given” and it would be idle to quarrel with it, to try to revise or efface it.

A millennial belief in a Holy God may have the effect of deepening the soul, but it is also obviously archaic, and modern influences would presently bring me up to date and reveal how antiquated my origins were. To turn away from those origins, however, has always seemed to me an utter impossibility. It would be a treason to my first consciousness to un-Jew myself. One may be tempted to go behind the given and invent something better, to attempt to reenter life at a more advantageous point. In America this is common, we have all seen it done, and done in many instances with great ingenuity. But the thought of such an attempt never entered my mind. Thus I may have been archaic, but I escaped the horrors of an identity crisis.

There were, however, other crises to face. As a high school boy reading The Decline of the West I learned that in Spengler’s view ours was a Faustian civilization and that we, the Jews, were Magians, the survivors and representatives of an earlier type, totally incapable of comprehending the Faustian spirit that had created the great civilization of the West, aliens whose adaptive strategies or mimicries were based on blind survival methods or deceits. Thus Disraeli, often called the greatest of nineteenth-century statesmen, didn’t actually know what he was doing.1 He could not naturally enter into the English spirit and he succeeded only by study and artifice.

Advertisement

Reading this, I was deeply wounded. I envied the Faustians and cursed my luck. I had prepared myself to be part of a civilization, one of whose prominent interpreters (Spengler was an international best seller) told me that I was by heredity disqualified. He did not say that I must be put to death, and one might be grateful for that. Yet he did pronounce Jews to be fossils, spiritually archaic, and that was in itself a kind of death. I was, however, an American Jew, not a German or a French Jew, and everything in America was different. My boyish hunch was that America, the enlightened source of a liberal order, might be a new venture in civilization, leaving the Faustians in the rear. So that what Magians were to Faustians, Faustians might very well be to Americans. By such ingenious means, I held Spengler at bay.

Later I discerned a kind of Darwinism in his kind of history—mankind advanced by evolutionary stages. In the natural history museum I couldn’t reconcile myself to the surrounding pterodactyls and ammonites, to standing on a forgotten evolutionary siding. It did no harm to picture myself in a museum. On the contrary, I realized that I didn’t belong there.

Having begun this talk without an adequate perspective, I now begin to see an intent in it. The condition I am looking into is that of a young American who in the late Thirties finds that he is something like a writer and begins to think what to do about it, how to position himself, and how to combine being a Jew with being an American and a writer. Not everyone thinks well of such a project. The young man is challenged from all sides. Representatives of the Protestant majority want to see his credentials. Less overtly hostile because they are more snobbish, the English want to know who he is or what he thinks he is. Later his French publishers will invariably turn his books over to Jewish translators.

The Jews too try to place him. Is he too Jewish? Is he Jewish enough? Is he good or bad for the Jews? Jews in business or politics ask, “Must we forever be reading about his damn Jews?” Jewish critics examine him with a certain sharpness—they have their own axes to grind. As the sons of Jewish immigrants, descendants of the people whose cackling and shrieking set Henry James’s teeth on edge when he visited the East Side, they accuse themselves secretly of presumption when they write of Emerson, Walt Whitman, or Matthew Arnold. My own view is that since Henry James and Henry Adams did not hesitate to express their dislike of Jews there is no reason why Jews, while full of respect for these masters, should not be free to write as they please about them. To let them (the hostile American WASPs) determine once and for all what the American psyche is, not to challenge their views where those views are narrow, or to accept the transmission of European infections and racial poisons would be disloyal and cowardly.

On the other hand one can’t always be heroic, and there were times when shades of Brownsville and Delancey Street surrounded Jewish lovers of American literature and they were unhappily wondering what T.S. Eliot or Edmund Wilson would be thinking of them. Among my Jewish contemporaries, more than one poet flirted with Anglicanism and others came up with different evasions, dodges, ruses, and disguises. I had little patience with that kind of thing. If the WASP aristocrats wanted to think of me as a Jewish poacher on their precious cultural estates then let them.

It was in this defiant spirit that I wrote The Adventures of Augie March and Henderson the Rain King: “I am an American,” etc. But of course I was not so simple-minded as to think I had satisfied certain persistent and deadly questions. Those were repeatedly thrust upon me by everyone including Jewish writers and thinkers whom I held in great esteem. Back in the Fifties I visited S. Agnon in Jerusalem and as we sat drinking tea, chatting in Yiddish, he asked whether I had been translated into Hebrew. As yet I had not been. He said with lovable slyness that this was most unfortunate. “The language of the Diaspora will not last,” he told me. I then sensed that eternity was looming over me and I was aware of my insignificance. I did not however lose all presence of mind and to feed his wit and keep the conversation going, I asked, “What will become of poets like poor Heinrich Heine?” Agnon answered, “He has been beautifully translated into Hebrew and his survival is assured.”

Advertisement

Agnon was of course insisting that the proper language for a Jewish writer was Hebrew. I didn’t care to argue the matter. I was not in a position to dismantle my entire life and start again from scratch in Hebrew. Agnon did not expect me to. Without a trace of ill will he was simply directing my attention to certain chapters of Jewish history. He was sweetly needling me.

Gershom Scholem, whose books I admire, was less gentle with me. I am told that a statement that I was said to have made in 1976 when I won the Nobel Prize put him in a rage. I was quoted in the papers as saying that I was an American writer and a Jew. Perhaps I should have said that I was a Jew and an American writer. Because Scholem is one of the greatest scholars of the century, I’m sorry I offended him, but having made this bow in his direction, I allow myself to add that the question reminds me of the one small children used to be asked by clumsy Sunday visitors in olden times: “Whom do you love better, your Papa or your Momma?” I recognized that I answered the reporters unthinkingly, “writer first, Jew second.”

For easily understandable reasons Scholem immediately placed me among those German Jews who had done everything possible to assimilate themselves and of whom Lionel Abel has written (in The Intellectual Follies), “German culture was the culture of the gentile world” that was the most admirable. The tragedy of the German Jews, says Scholem (for Abel too is in this passage referring to Scholem), was “that they were destroyed by the nationalist political movement in the nation they loved best.”

This, like so many Jewish questions, is deeper and more tragic than it may appear. I shall examine it from my own standpoint, that of an American Jewish writer, and take the discussion back to Agnon, who needled me so sweetly about the vanishing languages of the Diaspora. One’s language is a spiritual location, it houses your soul. If you were born in America all essential communications, your deepest communications with yourself, will be in English—in American English. You will neither lie nor tell the truth in any other language. Without it no basic reckonings can be made. You will not reflect on your own death in Hebrew or in French. Your English is the principal instrument of your humanity. And when the door of the gas chamber was shut many of the German Jews who called upon God for the last time inevitably used the language of their murderers, for they had no other.

Some such recognition lay behind Agnon’s teasing warning. Teasing was his Jewish way of being serious with me. He argued that the soul of the Jew must turn its back on Europe and in the Edenic peace of the Promised Land contemplate Hochma [Wisdom]. Yes, but the Jews can neither bear nor afford to confine themselves to the Promised Land. Not even those who make Aliyah [immigration to Israel] can do without Western science, Western culture, Western financing and technology. How agreeable it would have been to study wisdom at Agnon’s feet. He said as much: he told me in Yiddish that if I had had enough Hebrew to understand him I would have longed to see him again (ihr volt noch mir gebenkgt). After the nightmare torments of Nazism we could settle down together at last to await the restoration of God’s kingdom.

This seemed to me not only a Jewish but also a European Jewish literary vision. In Europe Jews might be welcomed in almost every field of knowledge but as artists they would inevitably come up against a national or racial barrier. Wagnerism in one form or another would reject them. Goethe was infinitely more reasonable and balanced than Wagner, but even he wrote in Wilhelm Meister (third book), “…We do not tolerate any Jew among us; for how could we grant him a share in the highest culture, the origin and tradition of which he denies?” And Nietzsche wrote in Beyond Good and Evil, “I have not yet met a German who was favorably disposed toward the Jews.” He did not mean this to be a compliment to the Germans. And then in 1953 Heidegger, described by many as the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century, was still speaking of “the inner truth and greatness of National Socialism.”

A share in the highest culture, the origin of which the Jew himself denies? But it is rather the traditional culture which does the denying.

In twentieth-century Europe the métèque writers appear in considerable numbers. Métèque is defined in French dictionaries as “outsider” or “resident alien,” and the term is pejorative. The word appears in the OED as “metic,” although it is not in general use here. The novelist Anthony Burgess refers to métèques and makes a strong defense of the métèque writer—the nonnative who, being on the fringe of a language and the culture that begot it, is alleged to lack respect (so say the pundits) for the finer rules of English idiom and grammar, for “the genius of the language.” For, says Burgess, the genius of the English language, being plastic, is as ready to yield to the métèque as to the racially pure and grammatically orthodox:

If we are to regard Poles and Irishmen as métèques there are grounds for supposing that the métèques have done more for English in the twentieth century (meaning that they have shown what the language is really capable of, or demonstrated what English is really like) than any of the pure-blooded men of letters who stick to the finer rules.

Burgess’s Irishman is Joyce, his Pole Joseph Conrad, and we can easily add to his list Apollinaire in French, Isaac Babel, Mandelstam, and Pasternak in Russian, Kafka in German, Svevo in Italian (or Triestine), and for good measure V.S. Naipaul or Vladimir Nabokov. Indeed it is not easy in this cosmopolitan age to remove the métèques from modern literature without leaving it very thin.

I might have asked Agnon how well the Arabic of Maimonides had been translated into Hebrew. I lacked the presence of mind then, and even here my remark is slightly out of place.

In the US, a land of foreigners who may or may not be in the process of forming a national type (who can predict how it will all turn out?), a term like métèque or metic is inapplicable. To renew the purity of the tribe was a French project, and a man whose French is acceptable to the French is, at least in the act of speaking, a claimant to aristocratic status. But gentile New York and Brahmin Boston never dominated American speech, and the aristocratic pretensions of easterners were good for a laugh in the rest of the country. Yet when our own metics, the Jewish, Italian, and Armenian descendants of immigrants, began after World War I to write novels, they caused great discomfort, and in some quarters, alarm and anger.

Irving Howe has noted in a reminiscence of the Partisan Review days that

portions of the native intellectual elite…found the modest fame of the New York writers insufferable. Soon they were mumbling that American purities of speech and spirit were being contaminated by the streets of New York…. Anti-Semitism had become publicly disreputable in the years after the Holocaust, a thin coating of shame having settled on civilized consciousness; but this hardly meant that some native writers…would lack a vocabulary for private use about those New York usurpers, those Bronx and Brooklyn wise guys who proposed to reshape American literary life. When Truman Capote later attacked the Jewish writers on television, he had the dissolute courage to say what more careful gentlemen said quietly among themselves.

Capote said that a Jewish mafia was taking over American literature and New York publishing as well. He was to write in a later book that Jews should be stuffed and put in a natural history museum.2

I owe too much to writers like R.P. Warren, who was so generous to me when I was starting out, and to John Berryman, John Cheever, and other poets, novelists, and critics of American descent to complain of neglect, discrimination, or abuse. Most Americans judged you according to your merit, and to the majority of readers it couldn’t have mattered less where your parents were born.

Nevertheless, a Jewish writer could not afford to be unaware of his detractors. He had to thicken his skin without coarsening himself when he heard from a poet he much admired that America had become the land of the wop and the kike; or from an even more famous literary figure that his fellow Jews were the master criminals who had imposed their usura on long-suffering gentiles, that they had plunged the world into war, and that the goyim were cattle driven to the slaughterhouse by Yids. It was the opinion of the leading poet of my own generation that in a Christian society the number of unbelieving Jews must be restricted.

For a Jew, the proper attitude to adopt was the Nietzschean spernere se sperni, to despise being despised.

However disagreeable the phenomenon may seem at moments of sensitivity it is seldom more than trivial. The dislike of Jews was a ready way for WASP literati to identify themselves with the great tradition. Besides, it is something like a hereditary option for non-Jews to exercise at a certain moment when they discover that they have a born right to decide whether they are for the Jews or against them. (Jews have no such right.) At the beginning of the century it offered an opportunity to stand with distinguished intellectual groups of the right. How nice if you came from Idaho or Missouri to identify yourself with Maurras or the anti-Dreyfusards.

Henry Adams was particularly fond of Drumont, the anti-Dreyfusard journalist. Even the most enlightened minds if you investigate them closely have their kinky corners. As an example of kinkiness I offer the remark W.H. Auden made to Karl Shapiro after the Bollingen Prize was awarded to Ezra Pound: “Everybody is anti-Semitic sometimes.” True enough. We all know it and we are apt to give our favorites a pass, especially favorites on the whole so free from common prejudices as Auden, the most liberating of the modern English poets. He was in every important respect an exception—just as Capote was, in everything trivial, predictably nasty.

“We wanted to shake off the fears and constraints of the world in which we had been born,” Irving Howe said, speaking of the Jewish writers published by the Partisan Review in the Thirties and Forties, “but when up against the impenetrable walls of gentile politeness we would aggressively proclaim our ‘difference,’ as if to raise Jewishness to a higher cosmopolitan power.” As we have seen, the gentiles were not always polite. About the rest, Howe is quite right. He errs only in viewing the Jewish contributors to Partisan Review as a fully united group, identifying them as the “New York writers.” At least two of us thought of ourselves as Chicagoans who had grown up in a mixed district of Poles, Scandinavians, Germans, Irishmen, Italians, and Jews. The New York writers came from predominantly Jewish communities. I did not wish to become part of the Partisan Review gang. Like many of its members I was, however, “an emancipated Jew who refused to deny his Jewishness,” and I suppose I should have considered myself a “cosmopolitan” if I had been capable of thinking clearly in those days.

Delmore Schwartz, whom I looked up to, had written an essay calling T.S. Eliot the “international hero,” the poet who had most aptly defined the modern condition: shrinkage, decay, estrangement, disappointment, decline—civilization seen from the vantage point of classicism and aristocracy, all of it framed by a distinguished historical consciousness. I did not fit into any of this. In fact I would have been, in Eliot’s judgment, part of the decay and part of the reason for his disappointment. It wasn’t that I had any relatives who in the slightest resembled Rachel née Rabinovitch, who tore at the grapes with murderous paws, but I did feel that I would be consigned to a very low place in Eliot’s historical consciousness. Of course I resisted yielding a monopoly to this prestigious consciousness. I suspected that it was untrustworthy, and despite its attractive and glamorous wrappings I believed it to be more sinister than the simple nihilism of the streets. History? Certainly, but in whose version—whom shall we trust to summarize it for us?

I saw, in T.S. Eliot and in Joyce and the other eminent figures of their generation, history as artists since the end of the eighteenth century had understood it—romantic history. Artists, even the most radical, had orthodoxies of their own, and held orthodox views of the history of the West. I saw in art itself, when art was what it could be, a source of new evidence that did not necessarily confirm the judgment on modern civilization as formulated by its most prestigious writers. Art could not be limited by their final judgments. Closed opinions precluding further discoveries resembled, to my mind, a rigged auction.

But I think I may be spending too much time on the culture bosses who dominated writers and ruled over English departments and literary journalism. A genteel dictatorship inspired by T.S. Eliot (with a roughneck faction headed by Ezra Pound) and describing itself as traditionalist was in fact profoundly racist. But such things are ultimately without importance, merely distracting. What is imposed upon us by birth and environment is what we are called upon to overcome. The business of the Jewish writer, as Karl Shapiro rightly says in his indispensable book In Defense of Ignorance, is not to complain about society but to go beyond complaint.

These merely social matters (unpleasant, uncomfortable) are reduced to triviality by the crushing weight of the Jewish experience of our own time.

—This is the first of two parts.

This Issue

October 27, 2011

Energy: Friend or Enemy?

How Doctors Can Rescue the Health Care System

-

1

Spengler does say that the Jews could not understand the course of European history in which they were sometimes actors, but in fact points to Disraeli as an exception, someone who had the material power to act to manipulate the (to him) alien culture of England. See Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, Vol. 2, translated and with notes by Charles Francis Atkinson (Knopf, 1928), pp. 319–320. ↩

-

2

Capote’s text was as follows (“A Day’s Work,” Interview (June 1979), reprinted in Music for Chameleons (Random House, 1980), p. 158):

Mary: …Mr. and Mrs. Berkowitz. If they’d been home, I couldn’t have took you over there. On account of they’re these real stuffy Jewish people. And you know how stuffy they are!

Truman Capote: Jewish people? Gosh, yes. Very stuffy. They all ought to be in the Museum of Natural History. All of them.

↩