Jumping the shark is an idiom used to describe the moment in the evolution of a television show when it begins a decline in quality that is beyond recovery. It is synonymous with the phrase, “the beginning of the end.”

—Wikipedia

It is puzzling that there should be no close equivalent in other European cultures for the English country house drama, as known through novel, film, television series, and the stage. English it is—not, for once, more correctly British. A Scottish country house would imply a very different kind of story, while a Welsh country house (on any great scale) is a rarity. The French and the Germans have their country houses in plenty, but they are too discreet to prompt such universal fiction. Steam trains do not draw up at local Spanish or Italian stations, bringing the weekend guests. There are few manservants laying out the clothes before dinner in Belgium. One wonders really how Europe managed at all.

The greatest rival to the English country house tradition is the Russian, with its rich suggestions of a feudal system in decline, and with its great questions hanging in the air: How shall I live to some purpose? How can I reform the world I know? Those who ask such questions may be querulous and ineffectual, but the questions themselves are intelligent and profound, whereas the great questions that hang over the English country house come, for the most part, from the far side of stupid: Can I score a personal triumph at the flower show while forgoing first prize for my roses? Can I secure my lord’s affection by pretending to go rescue his dog? (The answer Downton Abbey offers is yes in both cases.)

Our English stupidity is a point of pride for us. P.G. Wodehouse, whose spirit haunts the corridors of Downton, had the fundamental comic insight, when he made the manservant Jeeves well-read, cultivated, and sly, and his master Bertie Wooster genial, candid, and dim. So that, when Bertie occasionally rises to an apt Shakespearean adage—“And thus the native hue of resolution is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought”—he will always add the modest disclaimer: “Not mine—Jeeves’s.” The clever servant had been a stock figure in comedy way back in antiquity, but the master had never been so completely the servant’s creation as Bertie Wooster was.

Mr. Carson, the butler at Downton (Jim Carter), has a Jeevesian conservatism and sense of the decorums of country house life. Unfortunately, he is not blessed with the Jeevesian gift of total success at thwarting all comers. His master, the Earl of Grantham (Hugh Bonneville), commits the fundamental error of choosing his former batman from the Boer War, John Bates (Brendan Coyle), as his valet. In doing so, he has allowed his heart to influence his head. Bates has a limp and is therefore—as the rivalrous servants almost unanimously believe—unsuitable for the job.

This business, by the way, of officers giving employment to their batmen, their personal military servants, in later civilian life—this is or was a well-known cover for homosexual attachments. One went into the army and formed a passionate liaison with a man from another class. The war over, one brought the batman home, under pretext of valeting requirements. And while we have as yet (at the end of the second season, with a third already promised) no proof of any impropriety in the relationship between Bates and the earl—no eve-of-battle indiscretion on the veldt, no cuddles on the High Karoo—nonetheless we ought to treat with suspicion the bare story that, in some unspecified way, Bates saved the earl’s life in what was referred to as the African War.

Each of the characters in Downton Abbey is accorded a moral leitmotiv. In Bates’s case it is a pathological degree of discretion and loyalty to inappropriate objects. Bates has a foul wife (or had till she was poisoned), who had stolen some regimental silver—a crime for which Bates had nobly taken the rap and gone to prison. His refusal to explain any of this has dogged his limping career and caused unnecessary suffering to those who care for him and wish to help him. This misplaced nobility of spirit is the pudgy-faced Bates’s form of passive aggression. At the end of season two we leave him in prison, sentenced to hang, reprieved, ready for his appeal. A gay back-story could well prove the scriptwriter’s nuclear option.

The elements are already in place. The avowedly homosexual (or as he puts it, “different”) footman, Thomas (Rob James-Collier), felt thwarted when Bates first appeared on the scene. Fresh from a surreptitious affair with the Duke of Crowborough (Charlie Cox), whom he has attempted to blackmail over some love letters, Thomas determines to improve his lot, to rise above his present menial position. But an overambitious and presumptuous attempt at seducing an exceedingly glamorous guest, the Turkish diplomat Mr. Kemal Pamuk (Theo James), goes wrong, and leaves Thomas at the mercy of the randy Ottoman.

Advertisement

To avoid exposure and disgrace, Thomas helps Mr. Pamuk on a night-time expedition to the bedroom of Lady Mary Crawley, the eldest daughter of the earl. Mr. Pamuk presses his suit with irresistible vigor. Lady Mary (Michelle Dockery) yields to his embraces. But in a bold scriptwriter’s move, indeed a masterstroke of surprise, orgasm proves too much for Mr. Pamuk, who dies on the job. The young and the beautiful are not expected to conk out in this way, to take, as it were, the Nelson Rockefeller option. But soap opera scripts require that they do—that they hang from such periodical cliffs and that they sometimes fall from them.

The creator of the series, the actor and writer Julian Fellowes, aka Julian Kitchener-Fellowes, aka the Conservative peer the Baron Fellowes of West Stafford, Lord of the Manor of Tattershall, aka the romantic novelist Rebecca Greville, is married to someone who—were it not for the anomaly of our laws of primogeniture—would be in line to inherit the title of the present (presumably the last) Earl Kitchener of Khartoum. Step out into that blizzard of ancestors and you will understand why, if there is any puzzling detail in Downton Abbey, Fellowes has probably got it right.

I mention this apparently gratuitous detail in order to underline the central point of Downton Abbey. The (fictional) Earl of Grantham has three daughters, none of whom can inherit either the title or the estate or—a detail that may seem recondite—the fortune their American mother (played by Elizabeth McGovern) brought with her when, like Consuelo Vanderbilt, she rescued the said abbey and its impecunious family years back. The American money has been “contractually incorporated into the comital entail in perpetuity.” This entail “endows both title and estate exclusively to heirs male.”

To most people this kind of legal technicality may belong to a remote world. But we may suspect that when the Kitchener-Felloweses sit down to dinner, this theme of injustice (the couple thwarted of any prospect of the Khartoum title) won’t go away. And if you feel from time to time that the television series is attempting to enlist your sympathy for a cause that, in your own life, might rank as a low priority (the perpetuation of a gigantic nineteenth-century house and estate)—that is indeed the case.

Certain values the earl represents (benevolent paternalism toward employees, for instance, or the ability to see when his own inherited attitudes have become outdated and inappropriate) have been carefully chosen. And it is noticeable that the aristocrats in the series, even the ones who are supposed to be the most ridiculous, never lapse into the most offensive kind of upper-class drawl one would expect of them. Great care has been taken to keep them pleasant and approachable, even when the things they say are sometimes shown to be class-bound and unfeeling.

We (the English) look to programs of this sort for a kind of verisimilitude we would not ask of, say, a Shakespeare drama, or even of Jane Austen. We want the food to look like period food, and the kitchen and servants’ quarters (mostly filmed in Pinewood Studios) to be accurate portrayals of servants’ quarters. We are delighted to note that, say, the butler strains the vintage port through a napkin, or that the most fantastic points of servants’ etiquette (no maids, only footmen, serving at dinner) have been resurrected for our amusement. This is the documentary aspect to the drama—something it shares with an older classic series, Upstairs, Downstairs.

But not every visual aspect corresponds to historical reality. The story is set in North Yorkshire, but filmed in the south of England, and nothing we see on screen reminds one at all of the north. The inconceivably grand house is Highclere Castle in Hampshire, built in the nineteenth century by the architect of the House of Commons, an essay in “Jacobethan” (eclectic Italianate) style. The parish church is Bampton in Oxfordshire, and obviously built in Cotswold stone. The locations are used sparingly. For instance, we see park but no flower garden—Lady Mary refuses to show it to a visitor, in the aftermath of the death of Mr. Pamuk.

The misbehavior of Lady Mary—a youthful sin for which she was very unlucky to be discovered—pales in comparison with that of her younger sister, the spiteful Lady Edith (Laura Carmichael), who, learning in the course of time that Mr. Pamuk’s body had been found in her sister’s room and moved back to his own, in the early hours of the morning, by her sister, her maid, and her mother, writes to the Turkish embassy to inform them of this misdeed—thereby ruining Lady Mary’s reputation. The more one thinks about this letter, the less likely it seems that a conventional-minded young woman in her position would have dreamed of writing it, let alone signing it.

Advertisement

Is it here, then, that the series may be said to have jumped the shark—to have taken that crucial, unforgivable step into cheapness and desperation? Not for me, and clearly not for the millions who have loyally followed it and allowed themselves to be manipulated by it—sobbing here, gasping there, anxiously leaving the room, rushing back, cheering Lady Mary on as she moves on her erratic way forward to the right marriage with the middle-class distant cousin who is eventually due to inherit “her” money and estate. We understand that the genre is broad and calls for some broad strokes of the brush—as for instance when the first season begins with the sinking of the Titanic and ends with the declaration of war in 1914. These are clear, broad narrative strokes.

With the Titanic are lost the two heirs presumptive to Downton Abbey, the younger of whom had been due to marry Lady Mary, thereby keeping the whole inheritance question within the family. During the war, when the great house is made into a convalescent home for officers, a character with a horribly scarred face appears and claims, despite having an inconvenient Canadian accent, to be the younger heir presumptive.

Of course the fact that his head is swathed in bandages and anyway disfigured makes it impossible for those who knew the supposedly drowned youth, let alone the viewer, to come to any judgment at all on the evidence presented. It seems a cynical and desperate piece of plot-weaving, all too redolent of the lowest of the low soap operas. It trifles with our sympathies even as it exploits our horror at disfigurement. But what can one do? The Abbey has jumped the shark, and we are still left waiting to see how it all turns out. It’s not the end, but it is the beginning of the end, a reminder of how easy we are to fool. Great television? Good fun, without a doubt. It’s a large sentimental contraption, coming at us, as the first trains came at us in the early Age of Steam, with a man in front, waving a red flag as if to say: you have been warned.

Among the by-products of the series, one book stands out, Margaret Powell’s Below Stairs, which in its latest incarnation bears the subtitle “The Classic Kitchen Maid’s Memoir That Inspired Upstairs, Downstairs and Downton Abbey.” Powell was born in 1907, and what she describes in this memoir is an early life in service in the years after World War I, in London and on the south coast of England (nothing nearly as glamorous as Downton Abbey). First published in 1968, this appears to be a very honorable example of the editor’s art (the copyright line is shared with the dedicatee, Leigh Crutchley).

A tribute, too, to the achievements of adult education. Powell had as a child won a scholarship that her parents’ poverty prevented her taking up. Work as a kitchen maid came as a prelude to marriage and motherhood. The impulse to resume her education came from the desire to keep up with the conversations of her children, simply to understand what they were discussing when they talked about history, astronomy, or French. Clearly Powell had narrowly missed, in early life, the chance to become a teacher. So this is a book about class. Clearly, too, wherever her education had taken her, she would have been forced to choose between marriage and a job. Married women simply didn’t go out to work, then, she reminds us:

Working-class husbands bitterly resented the very thought that their wives should have to work outside the home. It seemed to cast a slur on the husband and implied that he wasn’t capable of keeping you.

So this memoir can also be seen as a product of 1960s feminism.

This Issue

March 8, 2012

Schools We Can Envy

Work, Not Sex, At Last

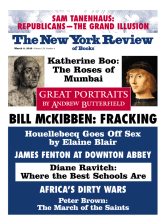

Why Not Frack?