Ramallah, Palestine

Amid the clamorous controversies of this election campaign, what strikes one here on the West Bank of the Jordan is the silences. Though the issue of Palestine promises to have a much more vital part in the volatile, populist politics of the Middle East’s new democracies—whose vulnerable governments actually must take some account of what moves ordinary people—here in Ramallah we have heard virtually nothing substantive about it, apart, that is, from Mitt Romney’s repeated charge that President Obama, presumably in extracting from Israel a hard-fought ten-month freeze on settlement building early on in his administration, had “thrown Israel under the bus.”

In fact, the West Bank is perhaps the place on the globe that has seen the least of President Obama’s promised “change you can believe in.” Nearly fifty years after Israel conquered the territories, its young soldiers are still on patrol, herding millions of Palestinians through and around an increasingly elaborate labyrinth of checkpoints, walls, and access roads, while Israeli settlers, now numbering in all more than half a million, flow over the hills, swelling their gated and fortified towns, creating one “fact on the ground” after another. Even as the land of the long-promised Palestinian state vanishes behind these barricades, the phrase “two-state solution” lives on, hovering like a ghost over the settlements, a remnant mirage of a permanently moribund “peace process” that has produced no agreement of consequence in twenty years, since the Oslo Accords vowed a Palestinian state would be declared no later than 1999.

Governor Romney’s own view of how to achieve Middle East peace is decidedly more modest—indeed, almost Buddhist in its fatalism. As he told guests at the now-infamous Boca Raton “47 percent” fund-raiser:

You hope for some degree of stability, but you recognize that it’s going to remain an unsolved problem…. And we kick the ball down the field and hope that ultimately, somehow, something will happen and resolve it.

Whatever that “something” that will “somehow…happen” might be, it will presumably not come at the initiative of a Romney administration, since, as the governor went on, “The idea of pushing on the Israelis to give something up, to get the Palestinians to act, is the worst idea in the world.”1

Since this attitude mirrors that of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the governor’s former colleague at Bain Capital, it would seem to accord perfectly with Romney’s vow that “the world must never see any daylight between” the US and Israel. Five months after he made these statements, after his return as “ol’ moderate Mitt” in the first debate, Governor Romney declared that he would “recommit America to the goal of a democratic, prosperous Palestinian state living side by side in peace and security with the Jewish state of Israel”2—a “goal” Prime Minister Netanyahu has also publicly embraced, no doubt with like sincerity.

The blanket of near silence cast over the Middle East “peace process” extends south and east, to the United States’ most active current “shooting war”—the undeclared and seemingly permanent covert war being fought mostly with unmanned drones in South Asia and, increasingly, the Horn of Africa. Every day, twenty-four hours a day, American airmen serving their shifts at bases in Nevada, upstate New York, and elsewhere in the United States are “piloting” these lethal flying robots, gazing at computer screens through which they track from above the movements of men on the other side of the world.

Sometimes the men they shadow in Pakistan and Yemen and Somalia are known militant suspects (targets of so-called “personality strikes”), sometimes they are “military-aged” men behaving in ways deemed to fit with known terrorist “profiles” (so-called “signature strikes”). In either case the land-borne pilots, whether working for the Central Intelligence Agency or the United States military, spend their hours and days observing them—and often pulling the trigger that launches the missile that streaks down and kills them. These pilots working quietly on US bases have so far killed several thousand people—credible estimates range as high as 3,500—and perhaps as many as one in four have been noncombatants.3 At least four executed in this manner have been American citizens.

This quiet war, President Obama’s “focused” version of George W. Bush’s Global War on Terror, shows no sign of coming to an end. No doubt some of those killed pose an imminent threat to American citizens—though the definition of what exactly that means, what criteria must be satisfied for our government to order someone’s death, remain classified and unmentioned. But there is much evidence to suggest that many, at least by any reasonable definition of “threat,” do not—indeed, that in as many as 94 percent of the cases the targets are “mere foot soldiers” about whom, according to terrorism expert Peter Bergen, “it’s hard to make the case that [they] threaten the United States in some way.”4 What is not in dispute is that these killings of thousands of Muslims, conducted by remote control by a distant superpower, have caused enormous resentment and hatred of the United States in Pakistan and throughout the Islamic world, a consequence that helps revivify and perpetuate the political sentiments at the root of the war on terror.

Advertisement

More than a decade after the attacks of September 11, one might have thought a great democracy in choosing its leader could have found time at least to consider this ongoing and seemingly endless war: to debate, for example, whether the drone strikes, deeply unpopular as they are among Muslims, might be creating as many terrorists as they are killing; or to ask whether Americans truly believe that their president should have “the unreviewable power to kill anyone, anywhere, at any time”—including their fellow citizens—“based on secret criteria and secret information discussed in a secret process” with no judicial oversight whatever;5 or even to inquire of their leaders, actual or prospective, how many thousands will need to be killed in this manner before the war on terror could finally be declared at an end—if in fact it ever can be. Behind the targeted killings, does the Obama administration have a strategy that will bring this war to some conclusion? Does Governor Romney?

As I write, amid the inescapable racket over what may or may not have happened one afternoon in Benghazi, these basic questions about the drone war, like the question of Palestine, remain unanswered and indeed largely unasked, beneath the ocean of silence. When the moderator of the last debate finally uttered the word “drones,” Governor Romney was quick to say, “I support that entirely, and feel the president was right up to the usage of that technology,” and, having noted earlier that “we can’t kill our way out of this mess,” went on to call for “a far more effective and comprehensive strategy”—focused on education and economic development—“to help move the world away from terror and Islamic extremism.”

If the word “drone” has hardly been uttered—and if, when it finally was, the Republic challenger found himself vigorously supporting their use while spouting faintly progressive-sounding calls for regional development—it is not least because on this question, President Obama has taken a position so strongly in favor of unremitting military violence that he has left his Republican rival, struggle though he may to shoulder his way past him, no place to stand. On the lingering war in Afghanistan and the possible one in Iran, Romney and Congressman Paul Ryan have harshly criticized Obama’s policies even as they have largely embraced them. Caught in a vise of Obama’s devising, the Republicans find themselves pressed on one side by the president’s surge of troops into, and now withdrawal from, Afghanistan, and by his strong sanctions on Iran; and on the other side—should they be tempted to advocate perpetuating the Afghan war or starting a new one against Iran—by the country’s lingering fatigue with the wars begun by George W. Bush.

Obama’s dramatic escalation and prosecution of the drone campaign, his “surge” of troops into Afghanistan, his embrace of many of George Bush’s national security policies (including warrantless wiretapping and military commissions and indefinite detention) that he bitterly criticized during his election campaign, even his failure to investigate and perhaps punish the use of torture, or to pay the political price to fulfill the promise, embodied in his executive order, to close Guantánamo: all these policies, even as they have disappointed and appalled supporters of human rights, have served to fortify the president’s right flank, making him the first Democrat president since Harry S. Truman to enter a reelection campaign with few if any vulnerabilities on national security.

Truman is not a bad place to start if we want to make some sense of what has become the “Libya Scandal” or, simply, “Benghazi.” How could one begin to explain to a visitor from another world that during the campaign to elect the leader of the most powerful nation on the planet the single clamorous foreign policy “debate” concerns the circumstances of the death of a single US ambassador and three US employees in a small backwater city on the Mediterranean littoral? Perhaps one might begin by pointing out that American electoral politics have less to do with policies than with the manipulation of symbols and with the search to find and artfully present that particular complex of symbols that together most powerfully evoke the emotions desired—in this case, a sense of vulnerability, of loss of control, of looming threat, and of panic and fear—that can begin to make plausible the Republicans’ claim that what we were witnessing that afternoon in Benghazi, in the words of Paul Ryan, was “the absolute unraveling of the Obama administration’s foreign policy.”

Advertisement

President Truman would have well understood this, for it was he who in 1949 “lost China”—in the phrase his Republican adversaries coined to describe the Chinese Revolution—and thereby helped to begin a half-century of mostly Republican Party ascendancy when it came to national security and its governing cold war political question: In a world of unremitting danger, who can best keep us safe? In both cases, of course, the threats were real—though al-Qaeda’s terrorism, unlike, say, the Soviet nuclear arsenal, never posed an existential threat to the country. But what matters is extracting from that threat the political gold—fear, the most lucrative political emotion—and artfully inflating, maintaining, and exploiting it.

Out of these cold war origins—the world of “fellow travelers” and “security risks,” of “red-baiting” politicians for their being “soft on communism”—came the lineaments of the politics of fear that we saw reemerge in the War on Terror. Indeed, within ten days of the attacks President Bush was arguing quite explicitly that the two “wars” were continuous, insisting that the terrorists who had attacked New York and Washington were “heirs of all the murderous ideologies of the 20th century.”

By sacrificing human life to serve their radical visions, by abandoning every value except the will to power, they follow in the path of fascism, Nazism and totalitarianism.6

This powerful rhetoric firmly anchored the War on Terror in the familiar political constellation of a four-decade-long cold war that, when it finally ended a decade before, had deprived Republicans of their most potent foreign policy issue. The September 11 attacks restored it, as President Bush’s political Svengali, Karl Rove, pointed out a few months after they took place. “We can go to the American people on this issue of winning the war [against terror],” Rove told the Republican National Committee, “because they trust the Republican Party to do a better job of protecting and strengthening America’s military might and thereby protecting America.”7 And indeed a few months later, President Bush, following the most murderous attacks on America in the country’s history, accomplished what very few first-term presidents had before: he led his party to a decisive victory in a midterm election, winning back control of the Senate (with the help of a notable “terrorist-baiting” campaign against Senator Max Cleland of Georgia, in which a notorious advertisement superimposed the face of the severely wounded Vietnam war hero with that of…Osama bin Laden).

We still know little about the features of Ahmed abu Khattalah or the other leaders of Ansar al-Sharia, the “local militant group determined to protect Libya from Western influence”—in David D. Kirkpatrick’s description in The New York Times—that attacked the US consulate in Benghazi on the evening of September 11, 2012, and after “an intense, four-hour firefight,” burned it to the ground, leaving US Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and three other Americans dead. I daresay if one of Ansar’s leaders proves as photogenic as bin Laden, the airwaves and political advertisements will be flooded with his image soon.8 Whether we’ll ever know more of the facts of what actually happened that night is another matter. As I write they remain murky and disputed, notably regarding who exactly planned the attack and when, whether al-Qaeda really had any hand in it, and precisely how the evolving information about what happened made its way through the American government. Of course, the difficulty of answering definitively these central questions, and the drip drip drip of information emerging day by day, hour by hour, mainly from leaks within various parts of the government with their own interests at stake, are essential to keeping the scandal alive and thriving.

Early reports tell us that members of the group had been angered by the circulation on YouTube of a by-then-notorious “anti-Islam video,” and attacked the consulate in Benghazi. According to The New York Times, there was “some level of advance planning,” but according to Bloomberg News, the raid on the embassy was “a hasty and poorly organized act by men with basic military training and access to weapons widely available in Libya.”9 They assaulted the compound with mortars, rocket-propelled grenades, and, perhaps, an antiaircraft weapon. Unable to breach the consulate’s “safe room,” the militiamen set the building on fire using canisters filled with diesel fuel, trapping the ambassador inside. Looters later found him unconscious, overcome by smoke inhalation, and carried him to the hospital, where attempts to revive him failed.

For all the ambiguities, according to the Times, “Libyans who witnessed the assault and know the attackers” have “little doubt what occurred”:

A well-known group of local Islamist militants struck the United States Mission without any warning or protest, and they did it in retaliation for the video. That is what the fighters said at the time, speaking emotionally of their anger at the video without mentioning Al Qaeda, Osama bin Laden or the terrorist strikes of 11 years earlier.

Which is to say, though there appear to have been demonstrations against the YouTube video in Benghazi that evening, the attack on the consulate did not emerge from those demonstrations, as officials of the Obama administration initially maintained (and as did, it should be said, the Times and other reporters)—and as at least some officials were still maintaining five days after the fact. At the same time, while Republicans asserted with increasing vehemence that the attack was a pre-planned terrorist operation directed by al-Qaeda, they have produced no evidence to support that or to contradict the officials of the CIA’s National Counter Terrorism Center, who told Bloomberg News that “the al-Qaeda groups learned of the assault only after one of the attackers called to boast of it.”

Seizing hold of this rather unpromising germ of sordid violence, the well-tuned scandal machinery of the right—the oversight committees in the Republican-controlled Congress working hand in glove with ardent publicists on Fox News and other outlets—probed and exploited its ambiguities and, with the considerable help of the administration’s own initial mistakes, inflated it into, in Governor Romney’s words, an “attack by terrorists…[that] calls into question the president’s whole policy in the Middle East.” In this task they were helped immeasurably not only by the ongoing inability of intelligence officials and reporters to answer definitively some critical questions—such as the group’s true relationship to al-Qaeda—but by an initial shading of the story by some Obama officials that may have been politically motivated, for the wedge needed to broaden the disputed events of Benghazi into this broad indictment was the implication, and later the assertion, that the administration lied. Though President Obama did refer vaguely to “acts of terror” in his Rose Garden statement the morning after the attack, the insistence by other officials that the attack was “spontaneous, not premeditated” led Republicans to charge what has become necessary for the construction of any respectable American political scandal: a cover-up.

What was being covered up? Since the White House was “trying to sell a narrative, quite frankly, about the Mideast that the wars are receding and that al-Qaeda’s been dismantled,” as Senator Lindsey Graham, Republican of South Carolina put it, acknowledging that “an al-Qaeda-affiliated militia” had attacked the US consulate in “the first successful terrorist attack on our country since September 11, 2001”—the words are Ari Fleischer’s, George W. Bush’s former spokesman—would not only have undermined that story but revealed instead “the absolute unraveling of the Obama foreign policy.” The Republican vice-presidential candidate went on to shape that argument in familiar terms:

What we are witnessing is the projection of weakness. And that projection of weakness emboldens our adversaries and scares our allies. You see, if we look weak, our adversaries are more willing and more brazen [sic] to test us, and our allies are less willing to trust us. It’s a dangerous world. We are at war with terrorists. Let’s not forget that.

The words recall not only President Bush’s 2004 reelection campaign—when Vice President Cheney warned voters that “if we make the wrong choice then the danger is that we’ll get hit again and we’ll be hit in a way that will be devastating”—but echo cold war warnings not to “show weakness” before the monolithic power of the Soviet Union. Governor Romney expanded the analogy in his foreign policy address on October 8:

The attack on our Consulate in Benghazi on September 11th, 2012 was likely the work of forces affiliated with those that attacked our homeland on September 11th, 2001…. These attacks were the deliberate work of terrorists who use violence to impose their dark ideology on others…; who are fighting to control much of the Middle East today; and who seek to wage perpetual war on the West….

This is the struggle that is now shaking the entire Middle East to its foundation…a struggle between liberty and tyranny, justice and oppression, hope and despair.

We have seen this struggle before. It would be familiar to George Marshall. In his time, in the ashes of world war, another critical part of the world was torn between democracy and despotism.

In the face of this challenge, as the governor put it during the second debate on October 16, “the president’s policies throughout the Middle East began with an apology tour and—and—and pursue a strategy of leading from behind, and this strategy is unraveling before our very eyes.”

The logic here is shaky indeed: that Obama officials shaped their early accounts for political motives has by no means been proved; indeed, according to a report in The Wall Street Journal published on the morning of the third and final debate, the president himself “was told in his daily briefing for more than a week after the consulate siege…that the assault grew out of a spontaneous protest.”10 One might expect this information would dim the ardor of Republicans convinced that the administration was trying to cover up the facts. Still, whatever new leaks may or may not tell us in coming days about what the government knew, what happened in Benghazi seems a very far cry from the unraveling of the country’s Middle East policy.

But the terms here preexisted the event; the constellation of words and symbols meant to elicit apprehension and vulnerability and fear have been established by long practice and only await the “content” that will set them in motion. Still, this content, at least what we know of it so far, seems unequal to the task. It is as if a large, mechanical monster, complete with frightful grimace and bared teeth, has been dragged, clanking and clattering, back out on stage, but though the great old beast still engenders apprehension, the figure its masters are hoping to fit inside to reanimate it is simply too small and too puny to put it convincingly through its paces.

The second problem is that in place of Obama’s “unraveling” foreign policy Governor Romney offers little more than…Obama’s foreign policy, after adding a sprinkling of platitudes and a strong dose of nostalgia. A Romney administration would supply not a new initiative in the Middle East—an effort to address the Palestinian issue, for example—but…“leadership,” along with “confidence in our cause, clarity in our purpose and resolve in our might.” In practical terms, this would seem to mean maintaining Obama’s sanctions on Iran, and perhaps tightening them; pursuing Obama’s “real and successful transition to Afghan security forces by the end of 2014” while “evaluat[ing] conditions on the ground”; supplying arms through third parties to some factions of the Syrian rebels, as the Obama administration is reportedly already doing; “reaffirm[ing]” the country’s “historic ties” to Israel; and “deepen[ing] our critical cooperation with our partners in the Gulf.” President Romney would add fifteen new ships a year to the US Navy, doubling the current building program, and would “roll back President Obama’s deep and arbitrary cuts to our national defense”—though these do not in fact exist, having been agreed to with Republicans in a wholly notional budget deal (called “sequestration”). Finally, bringing together all these minute “initiatives,” we have the capstone in Romney’s foreign policy address:

There is a longing for American leadership in the Middle East…. It is broadly felt by America’s friends and allies in other parts of the world as well—in Europe, where Putin’s Russia casts a long shadow over young democracies…. I believe that if America does not lead, others will—others who do not share our interests and our values—and the world will grow darker….

The music is familiar here, the tunes a half-century old, but in the lyrics we find no new ideas, no creative policies—to deal with Egypt, for example, and the other challenges presented by the young, struggling democracies of the Middle East and North Africa. Here a new initiative on the Palestinian issue, vigorously pursued, might actually reduce the influence of extremist forces, and the anti-American sentiments on which they thrive, and help to stabilize struggling moderate governments of countries, like Egypt, that have long been allied to the US. But what we get is only a vague reference to negotiations and the hope, privately expressed and no doubt more sincere, that when it comes to this conflict a President Romney would “kick the ball down the field and hope that ultimately, somehow, something will happen and resolve it.”

Though Obama’s policies in the Middle East, after the grand rhetorical gestures at the start of his term, have been largely improvisational and opportunistic—and though those policies are now dangerously “unraveling”—to replace them Romney can offer only a longing for an imagined past in which aircraft carriers and the “leadership” they convey could keep the old familiar order, autocratic, sclerotic, predictable, firmly in place. Whatever else one can say about today’s Middle East, that order is largely gone. In response to the roiling political struggles that have overtaken it, we hear only a pale conjuring of fear, and behind that only silence.

Against this inarticulate longing stands President Obama and his ferocious prosecution of the war on terror. If the politics of fear has lost its magic for the Republican right it is not least because its methods have been co-opted by the Democrat in the White House, who has been relentless in hunting down terrorists, and those who may look like terrorists, and killing them by the thousands. No one can criticize him for investigating the CIA for torture, for he has conducted no such investigation. No one can attack him for abandoning President Bush’s indefinite detention policy because he has, in the case of the prisoners who “can neither be tried nor released,” regularized and legalized it. And no one can denounce him for closing Guantánamo because Guantánamo has not been closed.11

Indeed, Republicans, who reportedly plan to reinstate “enhanced interrogation techniques against high-value detainees” in a Romney administration, make the plausible claim that the president, after officially halting torture on his second day in office, has in practice avoided the knotty questions of interrogation, “enhanced” or otherwise, by managing during his war on terror to avoid taking prisoners.12 Drones have largely replaced the interrogation room. And our leaders and those seeking to replace them will not debate drone warfare because on this as on other pressing matters raised by our permanent war on terror there is no longer an opposition. Both parties have embroiled themselves full-force in the struggle to be tough, and tougher. If President Obama has made himself largely invulnerable to the politics of fear it is because he has to a great extent taken it over in advance by his cool and ruthless methods, and left little political space for discussion.

This then is the final silence of our election campaign, particularly resonant here in the hills of Palestine. Across eleven years of the war on terror, and two presidents, the politics of fear have not been forestalled, or banished, or defeated. The politics of fear have been embodied in the country’s permanent policies, without comment or objection by its citizenry. The politics of fear have won.

—October 24, 2012

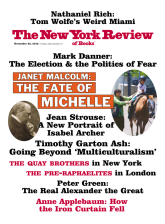

This Issue

November 22, 2012

The Winner: Dysfunction

Election by Connection

-

1

See “Full Transcript of the Mitt Romney Secret Video,” Mother Jones, September 19, 2012. ↩

-

2

“Romney Speech Transcript on Foreign Policy and His Plans for the White House,” Virginia Military Institute, October 8, 2012. The words “ol’ moderate Mitt” are of course former President Bill Clinton’s, in the wake of the first debate. ↩

-

3

ee “Covert War on Terror—The Data,” The Bureau of Investigative Journalism. ↩

-

4

See Greg Miller, “Increased U.S. Drone Strikes in Pakistan Killing Few High-Value Militants,” The Washington Post, February 21, 2011. ↩

-

5

See Rosa Brooks, “Take Two Drones and Call Me in the Morning,” Foreign Policy, September 12, 2012. ↩

-

6

See “Transcript of President Bush’s address to a joint session of Congress on Thursday night, September 20, 2001,” CNN.com. ↩

-

7

Scott McClellan, What Happened: Inside the Bush White House and Washington’s Culture of Deception (PublicAffairs, 2008), pp. 112–113. ↩

-

8

See David D. Kirkpatrick, “Suspect in Libya Attack, in Plain Sight, Scoffs at US,” The New York Times, October 18, 2012. ↩

-

9

John Walcott and Christopher Stephen, “Evidence Points to Hasty Strike on US Compound in Libya,” Bloomberg News, October 16, 2012. ↩

-

10

See Adam Entous and Siobhan Gorman, “Intelligence Stressed Libya Protest Scenario,” The Wall Street Journal, October 22, 2012. ↩

-

11

Today 166 detainees remain in Guantánamo, down from a peak of 779 under George W. Bush and 242 under Obama. See “Guantanamo by the Numbers,” Human Rights First. ↩

-

12

See “Interrogation Techniques,” a campaign policy paper written by former Bush and Reagan officials, which notes that “Governor Romney has recommended for years that a sounder policy outcome is the revival of the enhanced interrogation program” and urges him to “expressly endorse such an outcome during the campaign,” or risk “signaling to the bureaucracy that this is not a deeply-felt priority.” Also Charlie Savage, “Election to Decide Future Interrogation Methods in Terrorism Cases,” The New York Times, September 27, 2012. ↩