It’s hard to believe, but just twenty years ago China was on the verge of abandoning the market reforms that have since propelled it to its current position as a world power. Conservatives had used the 1989 Tiananmen massacre to reverse the country’s economic direction. Many felt that China needed to return to a more Soviet-style economic system, with stronger central planning and tighter regulation of people’s personal lives.

But China had a first-among-equals, Deng Xiaoping, who would have none of it. Although already an old man—he would die five years later aged ninety-two—he launched a brilliant guerrilla campaign. Almost surreptitiously, he left the capital in early 1992 for China’s freewheeling south, making speeches that extolled reforms. He declared that China’s biggest threat was from the left, not the right, and is credited with uttering the credo of China’s early reform era: to get rich is glorious. When conservatives blocked official media from carrying his remarks, he used his influence to publish his pro-reform message in regional newspapers. Eventually, the center’s resistance crumbled and Deng put economic reformers in key positions of power, unleashing a twenty-year boom. Political change remained off-limits, but almost anything else went; and it is defensible to say that China was freer and more dynamic than at any point in its modern history.

All of which brings us to today. Economic and political reformers are again on the defensive, with the economy increasingly dominated by pro-state forces that are squeezing private enterprise. The economy is slowing, with housing prices falling, foreign investment down, and consumer sales sluggish. Many economists advocating reforms of Chinese statism have been stifled—censors have banned the press and television from using the word “monopoly” in describing state enterprises. Socially, rising expectations mean people aren’t as easily satisfied with the Deng-era emphasis on achieving prosperity and enlarging personal opportunities; many also want to have more say over how their lives are shaped. But calls for political or social reform are blocked by a sophisticated “stability-maintenance” apparatus that keeps a lid on the tens of thousands of protests that beset the country each year and punishes outspoken critics of the regime.1

The new group of leaders, which takes over later this year, might have a raft of reforms in mind, but optimists are wary. Ten years ago most China experts proclaimed the incoming team of Party Secretary Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao to be laden with reformers; they turned out to be technocratic caretakers.

The difference between the stasis now and then is that China lacks a paramount leader like Deng who can challenge the logjam of competing interests, bureaucracies, and regions. Lacking the legitimacy that would be conferred by democracy or tradition, China’s current rulers must seek consensus, leaving them unable to challenge entrenched interests. Today’s China features Deng’s political repression but without his era’s dynamism—a country still hurtling forward, but its speed slowing and direction unclear.

Stagnant China? This isn’t the story that became accepted over the past decade. No country growing at double-digit rates could be thought of as declining; surely the label better describes sclerotic Europe or the politically paralyzed United States. The past ten years have seen a constant drumbeat of stories about China—either as the world’s next great thing or the next great enemy—but all repeating the mantra that China is changing, as if this were unique among the world’s nations. China fever peaked in 2008, first with Beijing hosting the summer Olympics and, after the global economic crash later that year, with China as the last bastion of global economic growth. Few then described it as beset by structural issues that would seriously hobble its rise.2

And yet this view is now widespread inside China, even at the highest echelons. Top leaders regularly invoke the need for systemic reforms, while Chinese economists say the next decade will be more important than the past three, when reforms were launched and China took off. The topic is also slated to be discussed at the upcoming Party congress, when China’s leadership for the next decade is to be appointed. A recent study by the World Bank and the Chinese government’s Development Research Center declared in uncharacteristically bold language that China risked crisis if it didn’t reform its system, adding that “calls for reform within the country have never been louder.”3

How China got to this point is the subject of three new books focusing on economics and business. All are written by highly qualified observers eager to make sense of China’s growing malaise. They come at it from different angles—one is a leading American essayist and journalist, another a Chinese government insider, and the third works at a Washington think tank—but their conclusions are strikingly similar: China needs more than a few tweaks to regain the dynamism of past years and reach a new level of development. All implicitly or explicitly make clear that most of all, China’s economic challenges are political.

Advertisement

The most ambitious of the three is James Fallows’s China Airborne. That might seem odd because Fallows focuses on one particular industry, aviation. But he uses it as a window on China’s effort to change its economy, something it must do during its next phase. Aimed at a general audience, it eschews many of the technical arguments found in the other two books, but for most readers it is an excellent one-volume look at the economic and political challenges of the post–China fever era.

One of Fallows’s great strengths is his impartiality and fair-mindedness. He starts out with sensible caveats, which too many—even those of us living in China—forget when speaking of this vast country of 1.3 billion. He says that what struck him most about living in China is how diverse it is, with regions as different from each other as many countries:

Such observations may sound banal—China, land of contrasts!—but I have come to think that really absorbing them is one of the greatest challenges for the outside world in reckoning with China and its rise.

His focus on aviation stems from his passion for flying—an earlier book of his discusses the aviation industry’s mess.4 This leads him to experience firsthand many memorable scenes. In one, he copilots a Cirrus propeller plane from an inland province to the coast. In between is a mountain range but air traffic controllers don’t respond to their requests to change altitude—a good example of the poor training and low standards that still are widespread in many professions. (Eventually, a commercial jet heard the pleas and relayed them to the controllers, who finally responded.)

Chinese aviation is a particularly telling subject. The country’s current five-year economic plan, which started in 2011, has China spending the equivalent of $200 billion on new airports, navigation systems, and planes. The country’s fleet is to increase to 4,500 planes from 2,600—representing half of new passenger plane sales in the world. The need is equally great: China has only 175 airports, compared with one thousand commercial airports in the United States, not to mention four thousand airstrips for enthusiasts and private pilots.

And here we begin to see China’s problems. China has a stunted civil aviation sector, not so much because of its level of development, but because of its authoritarian political system. Airspace is controlled by the military, with small corridors doled out to civilian use. In 2006, the military ordered Shanghai’s Pudong airport to shut down for several hours with no reason given—analogous, he says, to the US Air Force arbitrarily ordering Los Angeles’s LAX closed. The corridors are so narrow that flights pile up, while military restrictions force planes to fly at fuel-wasting low altitudes. This is a leading reason why Chinese domestic flights use twice the fuel per kilometer than the international standard, meaning that China could double its air traffic at no additional environmental cost if it simply adopted international norms. It’s one of the many fascinating facts that Fallows reveals, capturing at once the country’s hobbled civil society but also the opportunity for improvement.

Fallows also dissects China’s quest to build a passenger jet. The only manufacturer, the Commercial Aircraft Group of China, is in government hands. It has produced two models, mostly based on foreign technology, but neither is commercially usable, owing to their cost and weight. The lay reader may wonder why China can’t pirate a Boeing 737—an older model that is still a workhorse for many airlines. Fallows explains this by showing how much of China’s economic prowess is due to customers being “happy with crappy”—most don’t care that China’s products aren’t first-rate because they’re much cheaper. In the aircraft industry, this is less workable—how many airlines buy cheap but unreliable Russian planes?

China’s production methods are also unsuited to building ultra-complex machines: when assembling an iPad or a running shoe or even a car, if the first batch is defective, the manufacturer can adjust the production line and toss out the lemons. This works for much production in China but, obviously, wouldn’t work with aircraft. That leads Fallows to another memorable quote: “The Chinese can go to the moon long before they build an airliner.” A moon shot is a one-time event and requires brute engineering, while a jetliner is an immensely sophisticated amalgam of hardware and software that has to work flawlessly for decades.

Advertisement

Fallows argues that achieving this level of competence isn’t a given. To explain why, he detours to China’s education and political systems. Like the United States for many years after the September 11 terrorist attacks, today’s China is in a state of “permanent emergency,” in which the security apparatus is constantly cracking down. A string of events have convinced authorities that they are under siege: the 2008 Tibet and 2009 Xinjiang riots, the award of the Nobel Prize to Liu Xiaobo in 2010, last year’s Arab Spring, and now the leadership transition. Although many—probably most—Chinese remain happily ignorant of China’s parallel society of jails and guobao (secret police) agents, they sense it indirectly. Access to foreign websites in China, for example, is painfully slow because of the regime’s filtering software—a far cry from the 1990s, when China was ahead of the United States in cell phone networks, the then-cutting-edge telecommunications infrastructure. Once they are on the Internet, users will find that almost all foreign social media sites are banned.

Not getting onto Facebook might seem trivial, but it is a reminder to many Chinese—especially those educated abroad who might return home—that China is one of a handful of countries (the others are Iran, North Korea, and Syria) that permanently block this site, as well as YouTube and Twitter (most Google sites are accessible but often subject to cyber-harassment, such as slow loading speeds). The upshot, Fallows says, is that entrepreneurs will come to China to make money in such industries, but “this is not the place you’ll want to work if you want to be competing with the best.” And indeed most of China’s Internet platforms—Baidu, Weibo, Youku—are copycats of Western sites that are banned or hobbled in China. They are big and mostly profitable but not innovative.

As for China’s universities, they get high rankings in surveys that apparently don’t value academic freedom.5 But Fallows notes that few in the country who have a choice—not even Politburo members—want their kids educated there; if they can, they send their children abroad, especially to the United States. Meanwhile, a decade after joining the World Trade Organization, the country makes only minimal efforts to protect intellectual property, while the rule of law is often ignored. His conclusion: “A China capable of creating its own Boeing, its own Airbus, would have to be a transformed China from the one we know now.”

That isn’t the government’s view, of course. Along with energy, telecommunications, and defense, aviation is a sector over which the government has announced it will maintain “absolute control.” (It also says the state will maintain “strong influence” over automobiles, machinery, information technology, steel, metals, and chemicals.) In most of these sectors, state-owned firms enjoy monopolistic or oligarchic positions. Private firms, if they exist, face significant discrimination.

Such state planning has a long history in China, which we are reminded of when reading Justin Yifu Lin’s Demystifying the Chinese Economy. Born and raised in Taiwan, Lin is probably China’s most famous economist. For reasons still unclear, he swam over to China from a nearby island controlled by Taiwan in 1979 and was feted as a patriot. (In Taiwan, where he had been on military service, Lin is still officially a deserter and cannot return without facing arrest.) He became an advocate of market reforms and cofounded a research center at Peking University. He recently retired as the World Bank’s chief economist.

Lin’s book requires a fair amount of patience, not because it is particularly technical but because one has to plod through pages of politically correct mumbo-jumbo to get to the interesting bits. The history section is all but useless; his explanations are so flawed as to be interesting only if one wants to be reminded how official Communist historiography is a sequence of gloss-overs and half-truths. We learn nothing about land reform or Mao’s disastrous decision to emulate the Soviet economic model. Instead, Lin blithely concludes that “copying the Soviet model was a smart and practical option.” Even though the book is based on his lecture notes at Peking University, he pulls more punches than most economists inside China. At least for a foreign reader, the book comes across as painfully circumspect.

But another way of looking at his book is that—even though published by a prestigious academic publishing house—it isn’t meant to be a rigorous study; instead it’s to be read between the lines. And indeed with the help of a bit of Pekingology, it has value. His main point is that China first followed a “Comparative Advantage Denying” strategy but under Deng began to follow a “Comparative Advantage Following” strategy. This is Lin’s code for rejecting and then embracing market economics. It’s only toward the end that Lin gets to his point:

Since 2003 the Chinese government has been using macro controls to cool the economy, but it has not worked. Why? For a simple reason: the government failed to take radical action to tackle the cause, the increasingly inequitable distribution of income in recent years.

That has led to a wealth gap that is among the largest in the world, “with the unemployed and retired left behind.” The result is that “discontentment and grievances have begun to simmer in the community.” Policies over the past decade, he implies, have been of the old “Comparative Advantage Denying” variant; in other words, a turning back of the clock to state control.

After making these refreshingly clear statements, Lin then meekly prescribes a few general fixes without discussing the political implications—essentially begging the question of why these issues have languished for a decade. His main prescription is that state enterprises need to be privatized once they are “viable,” although he doesn’t say if most state enterprises are or when this might happen. He has nothing to say about fostering creativity or innovation.

Far more vigorous and systematic is Nicholas Lardy’s take on the past four years. Lardy, one of the preeminent economists working on China and a fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, has written a fairly technical book aimed at people who really care about the Chinese economy. Like Fallows, Lardy ends up pointing to the country’s political dysfunctionality.

Lardy starts by praising Premier Wen’s team in an opening chapter that will give pause to many China skeptics. He takes aim at foreign criticism of China’s 2008–2009 stimulus package, calling it “early, large, and well designed.” China rolled out a $586 billion stimulus in 2008, months before the Obama administration’s measures were passed into law. He notes approvingly that it was relatively much larger: the US package was $787 billion but for an economy two and a half times larger than China’s. Also, the Chinese plan almost completely focused on infrastructure projects—James Fallows’s airports, for example. By contrast, a third of the US stimulus measures were in the form of tax cuts, which households predictably put toward paying down debt—sensible for individuals but ineffective in stimulating demand. The result is that while the US and the rest of the world plunged into recession, China’s economy chugged along, somewhat slower but avoiding catastrophe.

China was better able to afford its hefty stimulus, he argues, because it had low levels of debt. Households and enterprises hadn’t been sucked into dangerous debt quagmires because China resisted Western advice to introduce fancy derivatives and other poorly understood financial products. Derided as too cautious, China’s mandarins began to look pretty smart—something worth keeping in mind when considering today’s predictions of doom.

Having praised China’s economic policymakers, Lardy proceeds to damn them. He writes that China’s leaders are aware that their policies are unsustainable. In 2007, Premier Wen told parliament that “China’s economic growth is unsteady, imbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable.” But it was precisely during Wen’s time in office that China’s economy went awry. Lardy points to political reasons: the leadership, he writes, is “focused on maintaining political stability by keeping inflation low and ensuring steady growth of nonagricultural employment.” These aren’t bad goals but instead of achieving them through reforms, Wen and his advisers resorted to sleights of hand.

Shortly after Wen took office in 2002, for example, China began holding down the rates paid on bank deposits, which kept credit cheap for the state-owned enterprises that get most bank loans. In addition, the exchange rate was held artificially low. Although the yuan has appreciated against the dollar in recent years, on a trade-weighted basis it only moved slightly.

From the government’s perspective, these policies funneled cheap capital (not to mention subsidized power and land) to state enterprises, which kept employment up and prices down. They also had the benefit of solidifying the role of state enterprises in a broad array of industries, which made conservative planners happy. The low exchange rate benefited export industries, which are located in China’s wealthy and politically powerful coastal provinces. This allowed China’s factories to hire the surplus labor that flows out of the countryside each year. All of this was designed to tamp down social unrest.

But as Lardy shows, these policies had many serious costs. Households began to earn an ever-shrinking share of China’s economic output. The low interest rates alone, he estimates, cost Chinese families the equivalent of $100 billion between 2002 and 2008. Unable to earn much by keeping money in the bank, many Chinese put their money in real estate, causing a huge property bubble that has yet to deflate. Other assets, from Yunnanese tea to contemporary art, also exploded in value, rippling across global markets.

Some government measures tried to help households. Over the past decade, China has set up a welfare and health insurance system and abolished many rural taxes that caused local unrest. But he shows that much of this has been eaten up by a “repressive” banking system and is too limited in scope. These measures were politically easy ways to spend money because they did not challenge vested interests.

If policymakers knew these problems were brewing, why didn’t they take course corrections? Lardy is typically succinct:

The emergence of a collective leadership system and the rise of special interest groups is a much more compelling explanation of China’s failure to pursue economic rebalancing policies more aggressively since 2004.

And yet the implication of this statement is bleak: surely no one can wish strongman rule on China. Perhaps, one wonders, the looming crisis may focus minds? These books were written before the current political crisis, when a member of the Politburo was suspended and his wife held on suspicion of murdering a foreign businessman. This Chinese leader, Bo Xilai, symbolized the confluence of statist economics and repressive social politics. In theory, his removal could weaken those forces, allowing the incoming leadership team of Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang to push through a Deng-style revolution. It is possible, but it is equally likely that Bo’s removal will force the new leadership to placate leftists. Already, state propagandists have hit back at economists who propose reforms. That many of them are politically liberal is no coincidence.

Fallows’s book provides an example of what could happen in China if it tries to muddle through. Instead of Boeings or Airbuses, China could produce the equivalent of Russian Tupolevs—second-rate airplanes that will only sell among captive customers at home or client states abroad. Is this China’s fate? Taking the long view, Fallows reminds us that we’ve been asking this question for decades:

The contradictory signals from China…make us eager for the choice to emerge, clearly and definitively, to end the suspense that has been building for forty years, since Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit, so we can know whether to regard China as friend or foe.

Wisely, he refuses to predict.

This Issue

September 27, 2012

Pride and Prejudice

Cards of Identity

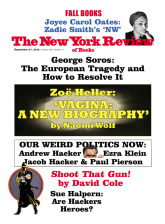

Are Hackers Heroes?

-

1

The exact numbers are impossible to ascertain but one estimate, by the Chinese scholar Sun Liping, puts the total number of “mass incidents” at 180,000 in 2010. This does not mean that China has five hundred riots a day, but it does mean that disturbances are widespread and, compared to previous estimates, that the number has increased significantly.

The country’s stability and security apparatus costs in excess of $100 billion, according to government figures, slightly more than the defense budget. ↩ -

2

Two notable exceptions are Gordon G. Chang’s The Coming Collapse of China (Random House, 2001) and Minxin Pei’s China’s Trapped Transition: The Limits of Developmental Autocracy (Harvard University Press, 2006). ↩

-

3

China 2030: Building a Modern, Harmonious, and Creative High-Income Society (World Bank, 2012), p. 65. ↩

-

4

Free Flight: From Airline Hell to a New Age of Travel (PublicAffairs, 2001). ↩

-

5

See, for example, www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/world-university-rankings/2011-2012/top-400.html. ↩