A very strange idea has spread in the Western media concerning Afghanistan: that the US military is withdrawing from the country next year, and that the present Afghan war has therefore entered into an “endgame.” The use of these phrases reflects a degree of unconscious wishful thinking that amounts to collective self-delusion.

In fact, according a treaty signed by the United States and the Karzai administration, US military bases, aircraft, special forces, and advisers will remain in Afghanistan at least until the treaty expires in 2024. These US forces will be tasked with targeting remaining elements of al-Qaeda and other international terrorist groups operating from Afghanistan and Pakistan; but equally importantly, they will be there to prop up the existing Afghan state against overthrow by the Taliban. The advisers will continue to train the Afghan security forces. So whatever happens in Afghanistan after next year, the United States military will be in the middle of it—unless of course it is forced to evacuate in a hurry.

As to the use of the word “endgame,” this might be appropriate if next year, upon the departure of US ground forces, the entire Afghan population, overcome with sorrow at the loss of their beloved allies, rolls over and dies on the spot. The struggle for power in Afghanistan will not “end” and US policymakers should not, as in the past, hop away from a swamp they’ve done much to create.

Two major new books, together with a number of lesser works, are crucial to an understanding of Afghanistan, the flaws of the Western project there, the enemies that we are facing, and therefore of possible future policies. Barnett Rubin, senior adviser to the US special representative for Pakistan and Afghanistan in the first Obama term, has been consistently among the wisest and most sensible of US expert voices on Afghanistan. His book Afghanistan from the Cold War Through the War on Terror is a compilation of his essays and briefing papers over the years, framed by passages looking back at the sweep of Afghan history and the US involvement there since 1979.

Peter Bergen is a former journalist and long-standing commentator and writer on the region now working at the New America Foundation in Washington, D.C.1 He has edited and introduces Talibanistan, a frequently brilliant collection of essays by different experts on the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan, including an analysis of the extent to which their past links with al-Qaeda represent an enduring threat to the West, and of how far a peace settlement with them may be possible. Rubin’s and Bergen’s works should be read in conjunction with a fascinatingly detailed new book by Vahid Brown and Don Rassler on the Haqqani network, the insurgent group led by Mawlawi Jalaluddin Haqqani and his son, which operates on both sides of the Afghan–Pakistani border. Its title, Fountainhead of Jihad, is the name of a magazine published by the Haqqanis.

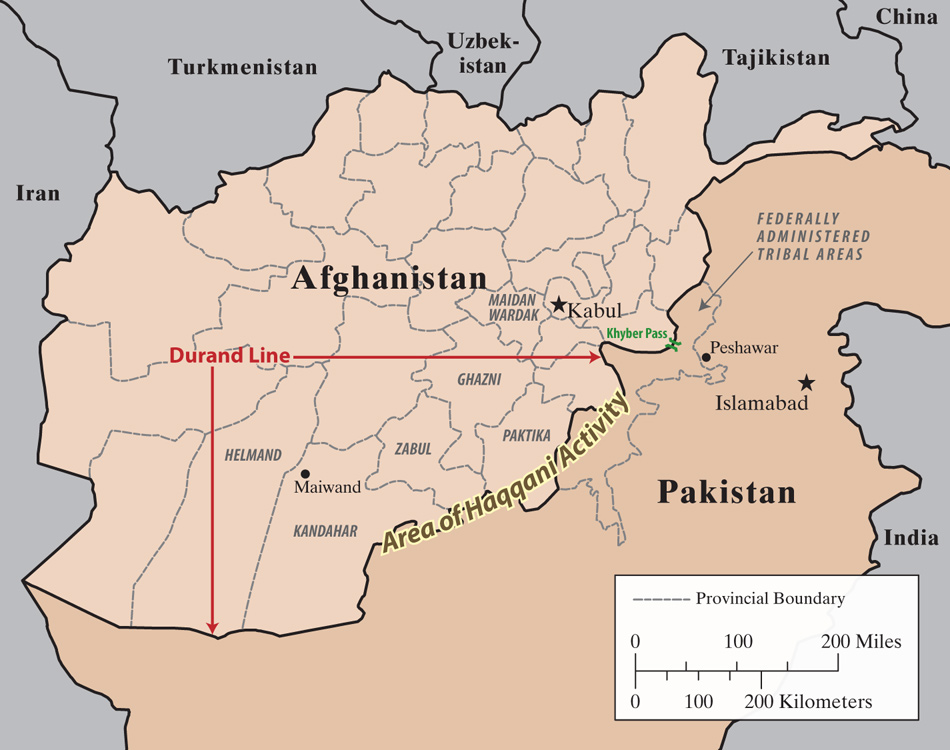

Brown and Rassler bring out the deep roots of the Haqqanis in the history and culture of this region, on both sides of the Durand Line, which was drawn up in 1893 by the British to mark the border between India (later Pakistan) and Afghanistan. As far as the locals are concerned it has always been largely theoretical. In the words of Jalaluddin Haqqani himself, “Our tribes are settled on both sides of the Durand line since ages. Our houses are divided on both sides of the border. Both sides are my home.” Brown and Rassler point out that from this point of view, all the US invasion of 2001 managed to do was “force this [Haqqani] nexus a few dozen kilometers east.”

The authors situate the identity and policies of the Haqqanis with respect to three powerful local traditions: first comes an ancient fight for local tribal autonomy against attempts to impose outside state power. This led the Haqqanis in 1999 and 2000 to clash with Taliban attempts to impose their own version of centralized Afghan rule. Next is a history of revolt in the name of Islam, orchestrated by local religious figures. Finally, there is the region’s long-standing role (in the phrase of the anthropologist James C. Scott) as the location for “shatter zones,” remote, usually mountainous areas that have not been fully penetrated and controlled by states, and that serve as refuges for a variety of fugitives and outlaws from elsewhere, who often create in these regions their own new communities. The refuge given to al-Qaeda can be seen as part of this tradition, as well as reflecting ideological affinities and material benefits.

Brown and Rassler see the very close relationship between the Haqqanis and Pakistani military intelligence, dating back to the 1990s, not as the Haqqanis acting as Pakistani agents, but rather as a pragmatic alliance with practical benefits for both sides. The Haqqanis get immunity from Pakistani attack and a measure of indirect technical and expert help. The Pakistanis gain a source of influence within Afghanistan and, equally importantly, in their struggle to contain their own Pashtun Islamist rebellion. The authors leave open the question of how the Haqqanis would respond to Pakistani pressure to enter into an Afghan peace settlement. Their first concern no doubt would be to preserve their own continued dominance in their own region.

Advertisement

A basic question raised by these books is what the Afghan experience of the past decade can tell us about the United States and its Western allies when they “go abroad in search of monsters to destroy.” Some lessons were taught by the Vietnam War, but then largely forgotten—mainly it seems because they were too offensive to America’s self-image. During the US debate—to give it that name—that preceded the invasion of Iraq in 2003, I was appalled by the extent to which the Vietnam experience had been forgotten: not so much lessons about the nature of guerrilla war and its horrors as about the United States itself.

These include the dangers of demonizing the enemy of the moment, on the basis of a belief that any enemy of the United States must inevitably be evil. Not only does this tendency make pragmatic compromises with opponents much more difficult (and much more embarrassing should they eventually have to be reached), but, consciously or unconsciously, it allows the US government and media to blind the US public, and often themselves, to the evils of America’s own allies.

The US did this again and again during the cold war. In Afghanistan it has done it twice: first in its blind backing of the often murderous and fanatical Afghan Mujahideen in the 1980s against the Soviet occupiers and their Communist allies; then, since September 11, against the Taliban—most of whose Pashtun footsoldiers are descendants of the same ordinary farmers who once filled the ranks of the Mujahideen, and who are now fighting for the same reasons of religious orthodoxy and hostility to outsiders. This is certainly not to say that either the Vietnamese Communists or the Taliban were or are desirable forces in themselves—just that they represent strong elements in their own societies, and from the point of view of many Vietnamese and Afghans, they are no worse than the forces that we support. Rubin, for example, is as aware of the grim treatment of women by the Taliban as anyone else; but he and some of Bergen’s contributors also find many American allies capable of widespread abuses.

The catastrophic difficulties that the Western intervention has faced in Afghanistan have been principally due to the realities of Aghanistan itself; but they have been made far worse by a series of policy mistakes, and the deeper features of Western government and society that they reflect. These began with specific and disastrous decisions by the Bush administration, which are mercilessly dissected by Rubin. The first, from which many of the others stemmed, was also in some ways the most forgivable. This was the decision in the days immediately following September 11 to give the Taliban the shortest of deadlines to hand the old al-Qaeda leadership over to the United States. The haste of the American response was understandable in view of the mood in the US following September 11. The result, however, was to make the US war effort disastrously dependent on warlords from the surviving anti-Taliban opposition, since they had the only armed forces on the ground.

According to Rubin, the hundreds of millions of dollars handed out by US officials to these figures went, among other things, to finance the restoration of the heroin trade, which the Taliban (for their own reasons) had temporarily suppressed. Afghanistan is now the largest producer of opium in the world, and the Taliban forces are deeply involved in its production. The results of this have not been much felt in the US, where heroin is a relatively minor problem—but they are all too apparent in Europe, Russia, and Iran.

These warlords not only were and remain dreadfully flawed figures in themselves but were detested by much of the Pashtun population in particular. This applies in the first instance to most—not all—of the warlords from non-Pashtun ethnic groups, grouped in the so-called “Northern Alliance,” who fought first against the Pashtun Mujahideen of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and then against the mainly Pashtun Taliban in the 1990s. But equally detested were the Pashtun Mujahideen warlords such as Gul Agha Sherzai, who dominated the south and east of Afghanistan after the fall of the Communist government in 1992. It was indeed to get rid of both these groups of forces that so many Pashtuns (and some others) had helped the Taliban to power in the first place. Rubin notes that a Western tendency to turn a blind eye to atrocities committed by anti-Taliban warlords against the Taliban predates September 11, and began with the UN’s indifference to such cases in the 1990s.

Advertisement

As described by Rubin and several of the writers in Bergen’s collection, the return of the Taliban in southern and eastern Afghanistan can be largely explained by the way in which the United States restored these warlords to local power, and then not merely allowed but in many cases actively helped them to eliminate local rivals. In a great many cases, this involved the persecution or even assassination of Taliban figures who had already expressed their desire to reconcile with the Karzai administration. One such former Taliban commander in Zabul province was Hajji Pay Mohammed, who was killed by the new local authorities after he had already agreed to lay down his arms. His body and those of his men were then publicly displayed for several days rather than being given to their families to be buried—an appalling breach of the Pashtun code.

In his chapter in Talibanistan, Anand Gopal writes that

many Taliban did not take up arms simply as an exercise of the principle of jihad or expulsion of foreigners…, but rather because it was the only viable alternative for individuals and groups left without a place in the new state of affairs.

Gopal describes the case of Hajji Burget Khan in the Kandahari district of Maiwand, some 350 miles southwest of Kabul. He was an elderly and respected local figure who had no personal links to the Taliban. US forces raided his house in 2002, killing him and leaving his son a paraplegic—an incident that was crucial in persuading local people to rejoin the Taliban. According to Gopal, “The most likely explanation [for the murder] is that the commanders with whom US forces had allied had seen Khan as a rival.”

I had a taste of this during a visit of my own to Afghanistan in early 2002, soon after the fall of the Taliban. During my trip, I met a lesser warlord known to the population of south Kabul as the “wolf man,” because he supposedly interrogated prisoners with the help of a pet wolf, to whom he then fed their remains. The truth more likely is that the wolf was a large dog and that the wolf man was employing some of the tactics later used by US interrogators at Abu Ghraib. But whatever the truth, he was not liked by local people, and the fact that the new authorities supported by the US had made him a local police chief did not increase public approval of them or their US backers. Resentment at the United States and its allies has grown so strong that on February 24, the Afghan government announced that it would bar American Special Operations forces from working in the strategically important province of Maidan Wardak, which lies just southwest of Kabul and frequently serves as a base for Taliban fighters attacking the capital. Afghans employed by the US military were said to have tortured and killed civilians there.

During the same trip, I met another warlord in Ghazni province who named for me a list of local former Taliban figures who he said had only pretended to accept the rule of Karzai. Mistaking me for a CIA officer, he offered to bring me their heads “packed in salt” in return for $100,000. A number of US officials, it seems, did not decline similar offers. Unfortunately, as I found again and again in Washington during those years, any attempt to urge reconciliation with parts of the Taliban was liable to be brushed away with some variant of the phrases “We don’t negotiate with evil” and “We don’t talk to terrorists.”

This reliance on hideously flawed local allies also, however, reflected two other disastrous features of the Bush administration: Donald Rumsfeld’s belief that wars could be won, and their gains secured, with very limited US forces that thereafter would maintain a “light footprint” in the countries conquered; and the decision—made, it would seem, immediately after the Taliban were overthrown—to attack Iraq. This meant that in the spring of 2002, before the US had even succeeded in driving many al-Qaeda elements from Afghanistan, US troops were already being withdrawn from there to retrain for the invasion of Iraq. At almost every stage thereafter, US ground troops were inadequate to the tasks facing them, and every subsequent increase in US and allied troops was an inadequate reaction to gains made by the Taliban.

Even these errors would not have been so bad had they not been combined with a second project that was utterly incompatible with the “light footprint” strategy. This was the plan to develop Afghanistan as an effective, centralized, modern, liberal, and democratic state. Given the nature of Afghan society and the almost complete collapse of Afghan state institutions, such a project could only have had the remotest chance of success if the West had been prepared to deploy large forces and enormous amounts of money and attention over a period of generations.

The decision to try to create a modern Afghan democracy revealed in part the fundamental flaw in Rumsfeld’s thinking that should be remembered before the US again launches a war to overthrow a regime: namely that, in Colin Powell’s words, if “you break it, you own it.” Having overthrown the Taliban rulers by December 2001, some form of government had to be put in their place. The vast extent of the Western project in Afghanistan was also, however, a result of the Bush administration’s adoption of the “Freedom Agenda” in the Middle East, largely to help justify the Iraq war. As in Afghanistan, the nonmilitary resources that the US was prepared to expend on this agenda were abysmally inadequate to realize its immense ambitions.

Europe bears its own share of the blame for this mismatch. On the one hand, the European Union and America’s NATO allies were pathetically anxious to demonstrate their importance to Washington by “nation-building” in Afghanistan. On the other hand, Europeans’ real commitment was even weaker than that of Americans. I remember in 2002 listening to a German official talking about how by 2006 Afghanistan would have had presidential and parliamentary elections, established a stable democracy, “and we can leave.” When I objected that nothing serious could possibly be achieved in such a time, the response was “Yes, but we have to tell the German voters that we are out of there quickly or they will reject the whole mission.”

Having inherited this mess, and having so far failed to resolve it either through victory or negotiation, how should the Obama administration proceed as it begins its second term? The first work that US officials should read in this regard is the last chapter in Talibanistan, the Afghan expert Thomas Ruttig’s essay “Negotiations with the Taliban”—a model of lucid analysis. As Ruttig writes, central to the problem is the number of forces and persons involved. A short and by no means exhaustive list of these includes, on the anti-Taliban side: the US government and military (which of course have their own serious differences); the Karzai presidency and clan, and their immediate allies; non-Pashtun warlords and other leaders opposed to the Taliban; and Westernized Afghan officials and NGO figures in Kabul.

Among the armed opposition, the list includes the Taliban under Mullah Omar (which also has potentially serious internal divisions); the Haqqani network; the Hizb-e-Islami of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar; the remnants of al-Qaeda in the region; the Pakistani Taliban; and anti-Indian terrorist groups based in Pakistan, some now in rebellion against the Pakistani state, others still allied to it. Then there are the other nations involved: Pakistan, and above all the Pakistani military and military intelligence service, India, Iran, China, and Russia.

Each of these distrusts all the others, including, not least, their own ostensible allies. By the same token, all fear any peace negotiations in which they are not included. Thus Karzai wishes to pursue talks with some Taliban leaders (though, as seems likely, to try to split the Taliban rather than to make a deal with the organization as a whole). But he detests talks between the US administration and the Taliban. Most of these actors are themselves internally divided. All have the capacity to damage peace negotiations, and most can destroy hopes for peace altogether if they choose.

I strongly support the argument of Thomas Ruttig that the first essential step for a US administration is to commit itself fully to a political solution, and not—as has too often been the case up to now—try to use talks to split and weaken the Taliban rather than reach agreement with the organization as a whole. Only a genuine commitment along these lines will allow Washington to play the part of an honest broker between all the forces I have outlined above. In Ruttig’s words:

Instead of the current double strategy of “shooting and talking” at the same time, it [the United States] should concentrate on “talking instead of shooting.” This means turning the tanker round, not steering it a bit more to the east or west. It would redefine the current understanding of “position of strength” away from strictly military terms to political and moral terms. In this framework, military means would be used only for self-defense (which includes defending Afghan institutions and their officials)…. Such a shift in the military approach would also significantly remove a major recruitment factor for the insurgents: civilian casualties.

The commitment then should be first and foremost to Afghan peace. This also serves the vital interests of the United States and its Western allies. For as long as the conflict continues, al-Qaeda will continue to have opportunities to make itself useful to the Taliban and the Haqqani network; and all the different armed actors involved will need to go on taxing the heroin trade in order to support their armed forces.

A peace settlement would also be a considerable boost to America’s image in the Muslim world; and perhaps most important of all, would allow for a reduction of the dangerous level of tension between the United States and Pakistan, which is a major source of radicalization in Pakistan and therefore of terrorist threat to the US and its allies—especially those like Britain that contain large Pakistani minorities.

Certain indications from the Taliban side are encouraging. In July 2012, I was part of an academic group that held conversations in the Persian Gulf with leading figures close to the Taliban.2 They told us that there is a widespread recognition within the Taliban that while they can maintain a struggle in the south and east of Afghanistan indefinitely, they will not be able to conquer the whole country in the face of the Afghan and international forces arrayed against them.

The crucial reason for this belief is that in their own estimate the Taliban have the support of only around 30 percent of the Afghan population. This is in accordance with a recent opinion survey by the Asia Foundation,3 and seems plausible, since it would represent around two thirds of the Pashtuns. We were told that the Taliban therefore recognize the need for compromise with other groups in Afghanistan (which I took to mean groups representing other nationalities such as the Tajiks).

However, they categorically ruled out any deal with the Karzai government, and insisted that there would have to be a national debate including the Taliban on a new constitution—though, interestingly enough, they also said that the constitution that emerged would probably not be very different from the existing one. They said that there can be no return to a pure “government of mullahs” as before September 11 and that any Afghan government would have to include technocrats, and allow modern education (albeit with women and men strictly separated). It is possible that this view reflects a growing awareness of Afghanistan’s mineral and energy wealth, and the need for a technocratic elite capable of exploiting it.

Finally, and most strikingly, they said that the Taliban might be prepared to agree to US bases remaining until 2024. This seems to reflect the greatest fear of the Taliban, and many other Afghans, that the country will fragment into different ethnic warlord fiefdoms backed by different regional powers like Russia and India, as occurred in the early and mid-1990s. Even a prolonged US presence, it seems, may possibly be acceptable if it helps prevent the Afghan National Army from disintegrating along these lines.

All of the figures with whom we spoke said that breaking with al-Qaeda would not be a problem for the Taliban—as long as this was part of a settlement, and not a precondition for talks. They reminded us that the Taliban leaders have repeatedly distanced themselves from international terrorism, and said that ordinary Taliban fighters also see al-Qaeda as non-Afghans who brought disaster on Afghanistan.

The people we talked to became highly evasive, however, when asked whether the Haqqani network would be willing to accept the views they had put forward. Brown and Rassler’s book also gives no definitive answer to this question. However, reading the evidence they present, and drawing upon the historical record of the tribes from whom the Haqqani forces are drawn, my own provisional conclusion would be the following: the Haqqanis will support any settlement that is acceptable to Mullah Omar and to the Pakistani military, and that leaves the Haqqanis in de facto control of their own region on the Pakistan frontier; as part of this they would be prepared to exclude any significant presence of al-Qaeda from that region. But on the other hand, nothing on earth will prevent this region from remaining a haven for smaller groups of assorted outlaws, since this has been the case for many hundreds of years.

The first thing that the Obama administration needs to decide, therefore, is whether it really wants Afghan presidential elections under the existing constitution to go ahead next year, in view of the immense twofold risk involved. First, such an election will make a peace agreement with the Taliban impossible in the short to medium term. Second, repetition of the widespread rigging of the vote of 2009 will render the result illegitimate as far as most Afghans are concerned, plunging the country into a deep political crisis just as US ground troops withdraw.

The alternative would be for the US to acknowledge the deep flaws in the existing constitution (which in truth was imposed on Afghanistan from outside), and to declare that it supports the idea of a new constitutional assembly. This would also help open the way to genuine peace talks with the Taliban. If the Obama administration cannot summon the nerve to take such a step, it will have to decide who it thinks would be the best candidate to be the next Afghan president.

The one thing the Obama administration cannot honorably and realistically do is to walk away from all this with the declaration that it is “a matter for the Afghans themselves.” This might sound modest and democratic, but it would in fact be an abdication of responsibility for an Afghan mess that is to a considerable extent of America’s own making; and responsibility to the American soldiers—the troop trainers and advisers and others—and officials who will be left in the middle of this mess after US ground troops withdraw next year.

This Issue

April 4, 2013

Surrealism Made Fresh

Controlling the Drones

-

1

Of which I am a nonresident senior fellow myself. ↩

-

2

The report of our group was published last year by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London. See Michael Semple, Theo Farrell, Anatol Lieven, and Rudra Chaudhuri, “Taliban Perspectives on Reconciliation,” at www.rusi.org/publications/other/ref:O504A22C99538B/. Subsequent developments suggest that the Taliban continues to hold the views we heard expressed. ↩

-

3

Afghanistan in 2012: A Survey of the Afghan People, published by the Asia Foundation at asiafoundation.org/publications/pdf/1163. ↩