In “The Tale of ’Abd Allah of the Land and ’Abd Allah of the Sea” from the Arabian Nights, a poor fisherman fails day after day to catch anything but at last, in answer to his ever more desperate prayers, he feels something heavy land in his net. Joyfully, he hauls it up, only to find a merman, who begs for mercy—and for fresh fruit and vegetables, which are greatly lacking under the sea, he tells his captor. He promises that if the fisherman will bring him the produce and then release him back into the water, he’ll return with lavish recompense. ’Abd Allah of the Land doesn’t believe him, but lets him go anyway out of the goodness of his heart.

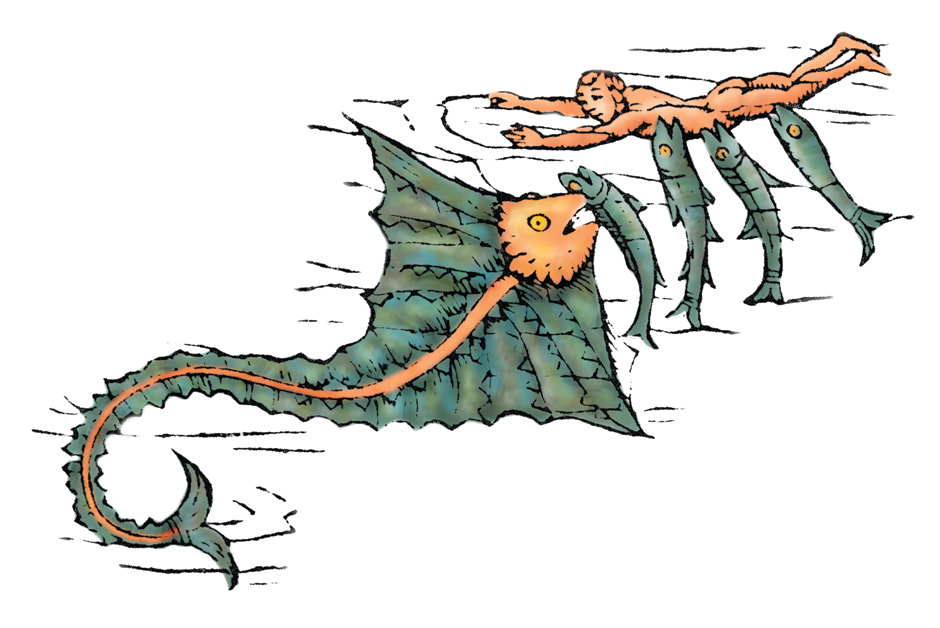

But this is a fairy tale, and so the merman will keep his word and rise again from the depths with basketfuls of fabulous gems from the sea bed—pearls and coral and chrysolites and other precious minerals—for his deliverer. Fruitful exchanges continue between them, and eventually, ’Abd Allah of the Sea invites his earthly friend down into the underwater world where, he tells him, he lives in one of many fine and diverse marine cities, each with its own society and culture. The fisherman protests that he will choke on seawater and drown. But the merman has a remedy: a powerful grease from a monstrous and terrifying fish called a dandan: “It is larger than any animal you have on land and were it to come across a camel or an elephant, it would swallow them up.”

The dandan’s liver—or in some versions of the tale its blubber—exudes a potent ointment that “looked like cow’s grease, golden yellow in colour, with a clean smell.” The substance is indispensable to mer-people for their own survival under the sea, but they cannot harvest it without human help. The monster is ferocious and deadly and voracious for flesh, mer- and other; however, it has a fatal flaw: it can’t abide the sound of a human voice. As the great fish approaches, intent on devouring him, ’Abd Allah of the Land must cry out. The mighty dandan will then keel over and die, and ’Abd Allah of the Sea will be able to harvest the precious secretion.

And so it comes about.

Now properly smeared all over in the wonder grease, ’Abd Allah of the Land is given a full tour of the extensive settlements, where different peoples and creatures dwell under the sea. He learns in amazement of the symbiosis between fish and humans, and then finds himself collected by the sultan of the sea for his cabinet of curiosities. When the merman’s mermaid daughters laugh at the fisherman for being “tail-less,” he’s hurt, and wants to go home and eat something besides raw fish; he is also affronted that the mermaids go about in the water bare-breasted and bare-faced, and speak their views so uninhibitedly. So he leaves the world under the sea.

This kind of fairy tale, as it brings the speculative imagination to play on surmises and glimpses of undersea conditions, strikes notes of delightful preposterousness. Much of the lore surrounding sea monsters exhibits the same wonderful mix of fantasy and observation, in which one can catch glimpses of whales and their valuable products, the vast lacy architectures of coral reefs, marine ecosystems, and pearl fishers’ experiences, all mixed up with sheer fancy. Several of the maps explored in these vivid studies by Chet Van Duzer and Joseph Nigg illustrate, for example, the unfortunate sailors who camp on a colossal fish they mistake for an island: they’ve made a landfall on its back and built a fire to cook themselves a meal, but when the beast feels the heat of the flames, it rouses itself and dives, taking the heedless picnickers to their death in the deeps.

This cautionary tale was so popular that the island-monster was given its own name: aspidoceleon, after its resemblance to a shield turtle, and the scene is widely illustrated and told—in the Romance of Alexander, the tale of Sindbad, and in the legend of Saint Brendan, in which the medieval monk glosses it as a warning that too much pleasure-loving idling and dalliance in this world will take you down to hell (see illustration below). Like other monster stories the aspidoceleon envisions a horrible—comically horrible—possibility, and issues a warning; but above all , it belongs to the literature of astonishment—mirabilia, in Latin, or ’ajaib, as in the Arabian Nights, and its tellers aim to astonish and delight.

Advertisement

The status of monsters is never stable: Are they fact or are they fiction? It is a question that early modern mapmakers do not answer. The two ’Abd Allahs reflect the theory, found in Pliny’s natural history, that “anything which is produced in any other department of Nature, may be found in the sea as well.” This fantasy proved convincing to many, although in the thirteenth century Gervase of Tilbury, mindful that sea creatures need to swim, added a touch of hybridity:

There is no form of any creature found living among us on dry land whose likeness, from the navel upwards, may not be observed among the fish of the ocean off Britain.

The terms sea horse, sea cow, and sea lion still enfold this dream of parallel plenitude, while in the past the catalog of sea creatures included every species: sea snakes, sea pigs, sea hares, and the appealing sea mouse that, according to Pliny, helps whales to see where they are heading by parting the heavy brows above their eyes.

While Chet Van Duzer, in his authoritative, wide-ranging study, and Joseph Nigg, who concentrates his full attention on the masterpiece made by Olaus Magnus between 1527 and 1539, strive to distinguish fantasy and reality in their accompanying texts, the pictures have such living presence (that quality of enargeia, the Greek ideal of vivid, hallucinatory representation) that the possibility of any monster—whale or dragon—remains just as likely as it is unlikely. And it must be said that their unlikelihood adds to the pleasurable curiosity such stories excite and feed, the delight in disagreeable and frightening things that Aristotle puzzles over toward the very beginning of the Poetics.

Both these sumptuously produced volumes about sea monsters place maps at the heart of scientific marine inquiry; the mapmakers attempted accurate documentation and measurement of land masses and coastlines but fill the surrounding seas with marvelous, terrible, and colossal fishes, serpents, sirens, and other creatures from the populous mythological cast—besides sea pigs, sea snakes, and sea horses, they include tritons, sirens, Scylla, Charybdis, the kraken, the remora, the grampus, the prister, each of them colossal, singular, and fearsome.

At the unknown beginnings of the world, gigantic monsters embody chaos and emergence, in Babylonian myth as well as in the fabulous classical zoo that Hesiod set down; he traces our anthropomorphic forebears—the Titans and Cyclopes and Olympians—back to terrifying gorgons and dragons and sphinxes. John Boardman has argued in his book The Archaeology of Nostalgia (2002) that the Greeks were attempting to make sense of dinosaur bones they found in the landscape, and he convincingly compares the bone-white sea monster on a vase, lurking in a cave and ready to pounce on Hesione, with the fossil skull of a Samotherium, or Miocene giraffe, such as was found around Troy.

But rational conjectures of this kind, however entertaining, don’t explain the whole activity of the monstrous imagination, which revels in excess and assemblage; tricephalous and multilimbed, with arthropod and reptilian features such as ruffs, tusks, fangs, tentacles, and jaws, many of these primordial monsters are hybrids defying nature. They belong to dark places, those underworlds under land and sea—volcanoes, ocean abysses—because they embody our lack of understanding, and mirror it in their savagery and disorderly, heterogeneous asymmetries of shape. For this reason, at the same time that Olaus Magnus was making his marine map, artists conjured extremes of physical monstrosity to convey spellbound states, in which perverse desires are spoken and thrilling moral transgressions follow.

The artist and art historian Deanna Petherbridge, with her selection of mostly printed images for the exhibition “Witches and Wicked Bodies,” explores how some of the most powerful artists—from Dürer to Goya, Jacques de Gheyn to Fuseli—combine and recombine grotesque medleys of limbs and disfigure and exaggerate aging female bodies to express the terrors of witchcraft. These expressions of monstrosity stigmatize the flesh, especially old women’s, while also appealing to the viewers’ appetite for thrilling perversity; rather like modern British tabloids, lurid scenes of other people’s sins—night-flying and Sabbath orgies—are titillating even while they purport to condemn. (In the case of Goya, the targets are many, ferocious, and tragic.)

Monsters still fascinate precisely because they express what might lie beyond the light of common day. And as in the case of Goya’s dream of reason, the fear and awe monsters inspire can’t entirely be dispelled by enlightened investigations, neither in the past nor today. The ocean swirls in a condition of mythopoeic duality: it is there, it covers two thirds of the world, it is navigable and palpable and visible, but at the same time, unfathomable, stretching down in lightless space and into the backward abysm of time where every fantasy can be incubated.

Advertisement

Both Chet Van Duzer and Joseph Nigg explore maps as maps, with monsters as the decorative—and instructive—elements in the mapmakers’ repertory, and both bring the story into the present, showing how “the geography of the marvellous” has deeply imprinted the collective imagination and has naturalized ancient sea monsters through different media, including video games. Neither author widens out into relations with the Zodiac or cosmology, or dwells on the mythology of shape-shifting Proteus or the terrifying Old Man of the Sea, nor do they linger on the rich fairy-tale lore of undines and selkies.

Nevertheless, they prove the case for the maps’ importance to the continuing life of myth and, above all, to the present vogue for fantasy in film and fiction. Moby-Dick, the giant squid and other sea monsters in Jules Verne, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, and even the computer-generated mask of glaucous, waving, suckered tentacles that the actor Bill Nighy is condemned to wear in the role of Davy Jones in Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest reveal the near-indestructible longevity of the marine world picture that was crystallized by early cartographic visionaries. It’s also significant that both the volumes under review exemplify a new rich phase in the history of book production: digital magnification and reproduction have made practicable marvelous close-up details from every moment of the maps’ journeys, while the jacket of Nigg’s study unfolds into a full-color poster of Olaus Magnus’s masterpiece, mapping his native Scandinavia.

Olaus Magnus was the Catholic archbishop of Uppsala, who was ousted from his cathedral by the Swedish Reformers and took refuge in Danzig, and he may have been inspired by nostalgic pride in his lost homeland. He truffled the northern oceans with dozens of colossal and polymorphous mythic monsters, as if laying out a deluxe box of chocolates with glorious flavors and varieties, emerald green and crimson, frilled and bulbous, toothy, barbed, and serpentine. In 1555, he went on to add a learned commentary, in which he melded together classical fable and science, lore from bestiaries as old as the Sanskrit Panchatantra, dating to the third century BCE, with observations gleaned from Aristotle, Pliny, and the anonymous Hortus Sanitatis.

Chet Van Duzer’s study begins with the first mappaemundi in antiquity and the early Middle Ages; the author is an encyclopedic scholar of historical cartography, with a magisterial command of comparative knowledge and scrupulous attentiveness to detail, noticing the slightest drollery drawn in the waves. By contrast, Nigg shows a juicier interest in the myths and stories, and provides a useful, gleeful “sea monster key.” (“ZIPHIUS, a horrible sea monster that swallows a black seal in one bite…. ROSTUNGER…somewhat like a sea calf. It goes to the bottom of the sea on all four of its feet, which are very short.”) He also quotes most entertainingly from the anonymous 1568 English translation of Olaus’s commentary, which reads like a cross between Thomas Browne’s Pseudoxica Epidemica, an invention from Borges’s library of Babel, and a recovered gnomic relic of Middle Earth:

And not onely may we understand by sight that there are Images of Animals in the Sea, but a Pitcher, a Sword; Saws and Horses heads apparent in small Shell fish, Moreover you shall find Sponges, Nettles, Stars, Fairies, Kites, Monkies, Cows, Woolves, Mice, Sparrows, Black-Birds, Crows, Frogs, Hogs, Oxen, Rams, Horses, Asses, Dogs, Locusts, Calves, Trees, Wheels, Beetles, Lions, Eagles, Dragons, Swallows and such like: Amongst which, some huge Monsters go on Land and eat the roots of Trees and Plants: Some grow fat with the South wind; some with a North wind blowing.

The monsters teeming in the seas of Olaus’s lost native land, Nigg proposes, might have been aimed at warning off trespassing fishermen—monsters usefully policing the sea roads. This would account for the huge spouting creatures in Scandinavian and Icelandic waters, but the rest of the teeming bestiary displays that fabulist Catholic sensibility that the Protestants deplored as aberrant, and the archbishop’s entry on Sea Swine allegorizes the monster as the Protestant heresy: “the eyes on its scaly body their temptations…and its dragonlike feet the evil that they spread throughout the world.”

The word “monster” encloses a memory of monstrare, to show, as in “demonstrate,” and monsters were interpreted as revealing in many different ways: as in the Arabian Nights, the sea gave evidence of the plenitude and infinite variety of creation and the maps enriched understanding of the Book of Nature and its mirabilia. Artists working for the mapmakers portrayed elements of monstrosity with wonderful ingenuity, shuffling tusks, horns, fins, flippers, flukes, blowholes, tentacles, gills, scales, spikes, tails, and limbs to produce a catalog of jumbled creatures with eyes on their bodies and jaws on their tails and so forth. Many of these are “Poetical Animals,” as Thomas Browne called griffins, but others approximate whales and sharks, polyps and crabs, and in the view of these studies, the mappers were fumbling toward an empirical grasp, and trying to guide and protect navigators.

An echo of monere, to warn, may also sound in the word “monster,” and while sea monsters may have embodied physical dangers, they were also frequently taken to be divine portents—Leviathans to punish the wicked or prophesy doom. Olaus Magnus was facing both ways, backward to medieval allegory, forward to empirical inquiry; but ancient fears still suffuse Melville’s vision of the white whale and Ahab’s pursuit, while recently, when two dead oarfish were discovered in California, one eighteen feet long, the other fourteen feet, they were immediately connected, rather shiveringly, with a local legend that such colossal snaky deepwater fish only surface when an earthquake is pending.

Medieval and early modern mapmakers, before and after Olaus, invoke eyewitnesses, the kind that still report sightings of Nessie in Loch Ness. They are early travelers like Marco Polo, sailors, pilgrims, collectors of curiosities, and the mountebanks who showed wonders and freaks in their shows in Amsterdam, Venice, and London. Petrarch is one of the unexpected authorities—cited by the explorer Sebastian Cabot—for the remora, a monster that, though small in size, attaches itself to a ship, stalls it against wind and current, and sucks it under. In illustrations it looks like a gigantic wood louse.

Magnification and accumulation are the mapmakers’ principles. “The richest collection of sea monsters in any one manuscript” appears in the fifteenth-century Latin version of Ptolemy’s Geographia; Van Duzer has counted them: 476 in all, of which 411 are “generic,” leaving sixty-five “more or less exotic and interesting sea creatures.” These are pen-and-ink doodles, bobbing in a sepia sea of undulating lines; fanciful creatures drawn rapidly, spontaneously, and humorously, they are closer to mischievous marginalia than terrifying scriptural portents. The warnings that monsters issue do call attention to perils and evils, but they can also remind us what relief there can be in fancy, in the spirit of play. “More delicate than the historians’ are the map-makers’ colors,” wrote Elizabeth Bishop, and though the lines don’t describe the rich pigments on display here, they do apply to the light touch of some of the maps’ artists.

In the oceans charted here, the monsters are correspondingly huge: indeed hugeness, an attribute of sublimity, is a defining characteristic of monstrosity—Robert Hooke turned a common flea into a grotesque and terrifying apparition when he drew what he saw through his microscope at approximately 288 times life size. The Bible gave its authority to the existence of sea monsters, with its story of Jonah and the whale, and its blazing poetic invocation of Leviathan in the story of Job:

Who can open the doors of his face? his teeth are terrible round about…. Out of his mouth go burning lamps, and sparks of fire leap out. Out of his nostrils goeth smoke, as out of a seething pot or cauldron…. He maketh the deep to boil like a pot; he maketh the sea like a pot of ointment…. Upon earth there is not his like, who is made without fear.

The colossal sea dragons that blast and spout in the observed sea lanes of Olaus’s and others’ maps owe more to the furious rhetoric of the author of Job than to the sightings of mariners.

The gigantism of the monstrous is also an effect of an imagined, primordial time of emergence and infinite possibility. Even from a post-Darwinian perspective, the sea inspires wonder—and fear. Since the latest of the maps reproduced in these books were made, zoologists have found more and more extraordinary life forms deep in the ocean, with peculiar, rare properties: bioluminescence already has beneficial uses, and more are being researched, while the starfish and other animals’ ability to generate new limbs is being closely studied; the miraculous glass sponge, an intricate mesh of silica, has exceptional tensile strength and durability, and withstands high stress in ways that give new dreams to the architects of Gulf State follies.

Anxiety might be behind the encyclopedic impulse: knowing your monsters can help contain them. One particular section of the Indian Ocean pictured on the Catalan Estense mappamundi (circa 1460) displays three varieties of sirens, including a centaur-like, female hippocampus. With his keen eye, Van Duzer has noticed that blank spaces were left in the sea for a different artist to fill in later, an artist whose speciality would have been sirens. Indeed, Van Duzer reminds us that the majority of old maps do not show monsters—they were expensive and beyond most patrons’ reach. But when they could afford them, patrons wanted them.

Shakespeare, who was writing in the world that Olaus Magnus and his successors were charting, shows every sign of fascination with bestiaries and their legends and lore, and The Tempest, which was first performed in 1611, interestingly conveys this double nature of the monster, perpetually oscillating between illusion and actual presence. Caliban as monster—and a fishy-smelling one—is a phenomenon and a figment; on the one hand, the “savage and deformed slave” of the cast of characters is treated as a sport of nature, whom Trinculo and Stefano plot to capture and exhibit, but on the other, the play also reveals Caliban to be the subject of misprision by those who maltreat him. When Prospero says at the end of the play, “this thing of darkness I acknowledge mine,” his avowal could mean many things. But it patently shows us Prospero recognizing that the darkness belongs to him, too, figuratively.

The development of modern cartography unexpectedly produced a Counter-Enlightenment result: to make monsters real. Both authors assume that the mariners had seen something, which they had mistaken for something else, and then identified the phenomenon with an existing mythical monster—jellyfish are called Medusae, the remora becomes Echidna, zoology constantly poeticized according to prior imaginative construction. Did sex-starved sailors really mistake walruses for mermaids? Or even the swollen, ungainly manatee? A glossary at the back of Nigg’s book tentatively matches some of the marvels tossing in the sea charts to known species: the prister as sperm whale, for example. Cryptozoology, the science of imaginary monsters, only emerges as distinct from zoology and biology after the period covered by the maps that are explored with such rich delight in these two studies.

Some other tales of sea monsters are not so far-fetched, however, which makes them more deeply troubling. For example, when the chronicler Ralph of Coggeshall reported that in the year 1187 a wild man was fished up from the sea off the coast at Orford, in Suffolk, England, what can have happened?

The wild man was completely naked and all his limbs were formed like those of a man. He was hairy and his beard was long and pointed. Around the chest he was very rough and shaggy…he devoured fish raw rather than cooked, squeezing the raw fishes in his hands until all the moisture was removed and then eating them. He did not wish to talk, or rather did not have the power to talk, even when suspended by his feet and tortured….

He survived this treatment over a long period, but eventually “secretly fled back to the sea and was never seen again.” The chronicler concludes, “Whether this was some sort of mortal man, of whether it was an evil spirit inside the body of a drowned man or whether it was some fish in human form, it is not easy to tell….”

Neither author is much concerned with alternative myths of mingling and cooperation. Yet in the far distant past, there were stories told about humans and monsters that promised a mutual alliance: in the Arabian Nights, mortal men fall madly in love with jinn who live under the sea, as in “The Tale of Julnar the Sea-Born”; unlike European legends of man and sea creature (Undine, Rusalka), these interspecies marriages are not doomed.

Today’s sea monsters are less sublime frights than “beguiling” diversions. Yet “why mermaids still swim in our dreams” (as the poet Michael Symmons Roberts asks) leads to more questions about the structure of the minds that produce such marvels, comic and terrible, beguiling and ghastly. In Fishskin Trousers, a lyric drama inspired by the Wild Man of Orford, which was staged in England earlier this year, the playwright Elizabeth Kuti takes up the challenge that the monster from the sea sets us in modern times, when the ignorance he figures is no longer epistemological but ethical, and does not belong to him as much as to his tormentors: scientific overreach, as well as cruelty, exclusion, intolerance. The monstrousness of the monsters can still show us dangers, from the sea and from ourselves.

This Issue

December 19, 2013

Mike

An American Romantic

Gazing at Love