1.

Can President Barack Obama end the “war on terror”? As a purely semantic matter, it began in September 2001 when George W. Bush first used those words, and it ended in March 2009, when the Defense Department replaced the term with “Overseas Contingency Operations.” But the latter term has never caught on. The main reason is not that President Bush’s label sells more newspapers, or flows more easily off the tongue, but because the war itself goes on. We continue to fight al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and their ever-morphing “associated forces,” in Afghanistan and beyond. We continue to hold alleged enemy fighters in indefinite detention, effectively as “prisoners of war”—many for more than a decade now. The CIA and the military continue to kill people without hearings or trials, using unmanned drones. And as we have recently learned, the National Security Agency has dramatically expanded its surveillance activities, at home and abroad, in the name of gathering intelligence about our clandestine foes.

The “war on terror” was always a misnomer. Bush claimed that we were fighting all “terrorist organizations of global reach.” Shortly after September 11, at a time of national trauma, he asked Congress for an open-ended license to use military force “to deter and pre-empt any future acts of terrorism or aggression against the United States.” But Congress declined. Instead, it authorized military force against those who carried out the terrorist attacks and those who harbored them—al-Qaeda and the Taliban. Still, the conflict with al-Qaeda has lasted more than twelve years, and when we withdraw from Afghanistan in 2014, al-Qaeda will continue to exist. Even if not quite as limitless as Bush’s proposed war, this conflict is sufficiently ill-defined and endless to justify its still-popular label as the “war on terror.”

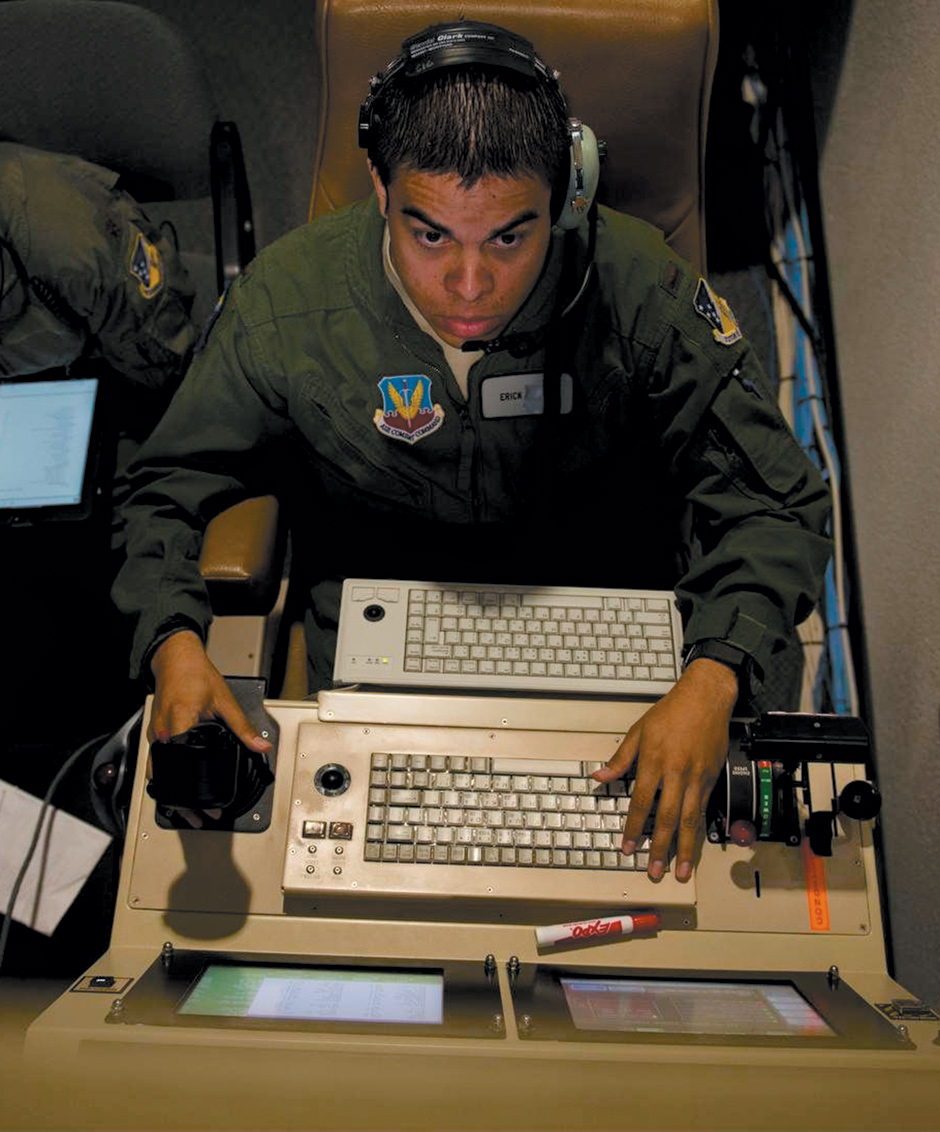

Some have suggested that this is a permanent state of affairs, and we might as well get used to it. As al-Qaeda continues to “evolve” and to inspire others to attack, the United States will continue to use military force to respond. Drones in particular can, at relatively low cost, monitor suspects remotely for months and then deliver bombs to execute them with the push of a computer button half a world away. They seem well suited to fighting clandestine, nonstate terrorist groups. When it works, the drone allows for the surgical elimination of threats without risking widespread loss of civilians’ or soldiers’ lives. (The number of civilians killed by drones is a matter of speculation and debate, but drones arguably cause less collateral damage than virtually any other form of warfare.) The pace of drone attacks has slowed in the last year and a half, partly because of increasing recognition of the resentment and backlash they provoke from local populations, but they are still an important weapon. When the US learned in late July of an apparent plan by the Yemen-based al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) to take action against US embassies overseas, the administration launched five drone attacks in Yemen in the course of two weeks.

Military detention also continues, with no apparent termination point. There are still 164 men held at Guantánamo. Many have been “cleared for release,” but Congress has erected substantial barriers to their transfers. The administration said in 2010 that there were forty-eight detainees who were too dangerous to let go but too difficult to try. A hunger strike in the spring brought the detainees renewed attention for a time, but in the past year, the administration has released only two of them.

As for surveillance, now that the NSA has developed the technological capacity and asserted the legal authority to collect, store, and search the “metadata” from all of our phone calls, and to collect and analyze the content of international e-mails, phone calls, and other electronic communications, why would it give that up—particularly as it claims that this has helped disrupt dozens of terror plots? Has the endless threat of terrorism brought us endless war?

Not if you believe what President Obama told the nation on May 23, 2013, when he addressed the subject of fighting terrorism at the National Defense University in Washington, D.C. In what could prove to be the most important speech of his tenure, Obama rejected the notion of “perpetual war,” quoting James Madison’s warning that “no nation could preserve its freedom in the midst of continual warfare.” Obama announced that he intends to bring the war on al-Qaeda and the Taliban to an end. Indeed, he claimed, “our democracy demands” it. Even as he threatens military strikes in Syria, this promise is apparently on his mind, and was reportedly one of the factors that led him to seek congressional authorization before taking action against Syria, thereby avoiding, for now, a resort to force. If Obama can make good on his intention to end the war with al-Qaeda, his Nobel Peace Prize of 2009 may be seen as prescient after all.

Advertisement

2.

What would it take to end the war with al-Qaeda? The first step is conceptual, but may be the most difficult: we must acknowledge our limitations. The end of the war will not be marked by the elimination of terrorism, or even of al-Qaeda. Nor does anyone expect a peace summit. Rather, the war against al-Qaeda will come to a close when whatever threat al-Qaeda continues to pose is manageable through nonmilitary measures. President Obama suggested that we are nearly there:

Today, the core of al-Qaeda in Afghanistan and Pakistan is on the path to defeat. Their remaining operatives spend more time thinking about their own safety than plotting against us. They did not direct the attacks in Benghazi or Boston. They’ve not carried out a successful attack on our homeland since 9/11.

The threat of terror certainly continues, as this summer’s closure of twenty-two US embassies in the Middle East and North Africa reminded us. The important point is that the continued existence of a threat, and occasional violence, do not necessitate a war. As Obama put it:

Neither I, nor any President, can promise the total defeat of terror. We will never erase the evil that lies in the hearts of some human beings, nor stamp out every danger to our open society…. We must be humble in our expectations that we can quickly resolve deep-rooted problems like poverty and sectarian hatred.

Humility has never come easily to the United States or its presidents. But that humility is the foundation of peace.

Terrorism is sometimes referred to as the price of living in an open society. But it is more fundamental than that: it is simply impossible to eliminate all terrorist threats, no matter what sacrifices we make. As Obama conceded in his NDU remarks, “Force alone cannot make us safe.”

Instead, we must learn to manage the risk of terrorism, just as we manage other unavoidable risks, including natural disasters, economic catastrophes, violent crime, and traffic accidents. It means arresting and trying terrorists, not simply killing them—as we must do with serial killers, rapists, and would-be assassins. It involves intelligence-gathering, diplomacy, foreign aid, and working to alleviate the underlying grievances that drive human beings to kill innocent people for political ends. As Malise Ruthven recently wrote in these pages, for example, these grievances may include those of traditional tribal groups on the periphery of the Arab world who feel that their ways of life are threatened.1 A multifaceted policy that sought to prevent terrorism through law enforcement, intelligence gathering, and diplomatic measures would not mean renouncing the use of force altogether, but limiting it to situations where it is truly necessary.

3.

The second step in resuming a peacetime footing is more tangible. It would require forgoing certain kinds of tactics that are available in an armed conflict, but not in peacetime—in particular, preventive detention and killing based on status. In wartime, an enemy fighter can be detained or killed merely because he is a member of the enemy’s fighting force, regardless of his conduct. In peacetime, by contrast, preventive detention is sharply restricted, and intentional killing is forbidden except in limited circumstances where necessary to prevent the loss of life or serious harm to another.

Thus, were President Obama to end the war with al-Qaeda, he would need a plan for closing Guantánamo and a more restrictive drone policy. Prisoners of war need not be released the day the war ends, but the justification for detention of anyone not charged with a crime would no longer exist, so a transition to release would be required. And while the US could still use drones in situations of true “self-defense,” it could not use them with anything like the frequency with which they have been deployed in recent years.

President Obama’s May 23 speech suggested that he is already moving in this direction. He reaffirmed his commitment to closing Guantánamo—not just formulaically, but in the strongest terms:

I know the politics are hard. But history will cast a harsh judgment on this aspect of our fight against terrorism and those of us who fail to end it. Imagine a future—ten years from now or twenty years from now—when the United States of America is still holding people who have been charged with no crime on a piece of land that is not part of our country. Look at the current situation, where we are force-feeding detainees who are being held on a hunger strike…. Is this who we are? Is that something our Founders foresaw? Is that the America we want to leave our children? Our sense of justice is stronger than that.

But of course he has wanted to close Guantánamo from the outset of his presidency and has not managed to do so. Obama has now taken some concrete steps, including lifting his own moratorium on repatriating detainees to Yemen, which was put in place after the foiled Christmas Day underwear bombing plot in 2009. Fifty-six of the eighty-four detainees already “cleared for release” at Guantánamo are from Yemen, as are many of those not yet cleared. The presence of AQAP in Yemen undoubtedly complicates the matter. But if we can support Yemen’s capacity to contain the threat that the detainees might pose upon return, a large portion of the Guantánamo population could be freed.

Advertisement

The president has appointed Cliff Sloan, a highly respected and able Washington lawyer, to coordinate detainee transfer for the State Department. But it’s no easy task. Other countries are understandably not lining up to take Guantánamo detainees off our hands, and Congress has imposed unrealistic restrictions on transfers, requiring assurances of no future harm that are extremely difficult to make.

The biggest challenge, however, is not Congress, or finding other countries to take detainees, but what to do about the forty-eight men whom the Obama administration identified as too dangerous to release but too difficult to try. In his speech, Obama expressed confidence that their cases could be resolved, but offered no specifics. Some may be subject to prosecution in other countries. Others may have become less dangerous. But if they can’t be convicted of criminal activity, we must release them when the war with al-Qaeda is declared to have ended. We must then live with the risk their freedom poses. Obama will not find it easy to take that risk. But prisoner-of-war detention must end with the war.

Some critics have cited the prospect of these men’s release as if it’s a rationale for continuing the war—but that is the tail wagging the dog. The war may authorize the detentions, but the detentions cannot authorize the war. The world will always contain dangerous individuals. The prospect of an additional several dozen is no excuse for extending a war that has for all practical purposes otherwise concluded.

4.

Limiting drone strikes may prove less difficult than closing Guantánamo, but no less crucial. Former State Department legal adviser John Bellinger has suggested that US drone policy has become “Obama’s Guantánamo.” Leaving aside whether Guantánamo itself is also now “Obama’s Guantánamo,” the drone policy has provoked nearly as much international criticism as the prison base. Dennis Blair, Obama’s first director of national intelligence, has argued that drone strikes have stirred so much resentment in Pakistan that they are counterproductive even if they hit their targets. Former CIA director Michael Hayden, retired general Stanley McChrystal, and former vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff James Cartwright have expressed similar concerns.2

But drones are not going away. Their ability to target enemy fighters in a surgical fashion is a significant tactical benefit.3 What is essential, however, is that their use be tightly constrained, precisely because they allow nations to bypass many of the pragmatic factors that have historically limited their resort to hostile force. In particular, in the absence of a war, drones may not be used to kill except where strictly necessary as a matter of self-defense.

The good news is that the Obama administration seems already to have moved toward a more restrictive and legitimate “self-defense” rationale. In his NDU speech and a “Presidential Policy Guidance” that he signed the previous day, Obama stated that he would authorize nonbattlefield drone strikes only where: (1) they are necessary to respond to individuals who pose a “continuing and imminent threat to the American people”; (2) capture is not feasible; (3) the host country is unwilling or unable to countermand the threat; and (4) there is a “near certainty that no civilians will be killed or injured.” This is a demanding standard, possibly even more demanding than the law of war, which does not require a near certainty that no civilians will be injured, but only that collateral damage be reasonably limited.

Nonetheless, serious questions remain. The policy is classified, save for a summary statement, as are almost all the details regarding actual strikes. Now that the administration has admitted it has a drone program, it is unclear why it can’t make public the precise standards and procedures it uses, as well as provide an accounting of its past—and future—killings, including civilian casualties. The power to kill without a hearing or trial, if it is to be lawful at all, must be subjected to transparent review.

And the administration still seems to be using an Orwellian redefinition of the concept of an “imminent threat,” the critical threshold to any exercise of self-defense. In past speeches and a “white paper” disclosed this year on the killing of Anwar al-Awlaki, a Yemen-based US citizen said to be an operational leader of AQAP, administration officials suggested that individuals may pose a “continuing and imminent” threat even if they are not engaged in or planning any particular attack at the time they are killed.

But the concept of a “continuing and imminent” threat seems in many instances to be a contradiction in terms. If a threat is truly imminent, it is unlikely to be “continuing” for very long.And a threat that continues for weeks or months hardly seems imminent. Al-Awlaki, killed in a drone strike in 2011, was on the “kill list” for more than a year before he was actually killed. What does “imminent” mean if someone can pose an “imminent” threat for more than a year?

And how exactly does the administration assess whether a suspect’s capture is “feasible”? Feasibility is not a static fact. If we had invested more resources in the Yemeni security forces, might it have become feasible to capture al-Awlaki? And there is a disturbing possibility that the advent of the drone may itself alter the assessment of what’s feasible, precisely because it makes it so much easier to kill than to capture. The fact that the Obama administration has killed thousands with drone strikes, while capturing only a handful of terrorists outside Afghanistan, has raised concerns that it has been too quick to deem capture infeasible.

Still, the number of drone strikes has dropped dramatically in the past year, suggesting that the administration may already be employing a more demanding standard than in prior years. In October, US forces captured a leading al-Qaeda figure in Libya and conducted an amphibious raid in Somalia in an unsuccessful attempt to capture an al-Shabab leader there. In both instances, the administration attempted capture rather than resort to drones. Ending the war on al-Qaeda would mean no more targeted killing of individuals based solely on their status as members of al-Qaeda or its “associated forces,” and instead limiting drone strikes to truly imminent threats of attack. Here, too, Obama seems to be moving in that direction.

5.

The implications of the resumption of peace for other controversial government policies are less clear. With respect to surveillance, we don’t even know the scope of the government’s programs, much less to what extent any surveillance is predicated on the existence of an armed conflict. The NSA programs that Edward Snowden has revealed, for example, rely on laws that are not limited to war, but broadly authorize the gathering of foreign intelligence in times of peace and war alike. And the Drug Enforcement Agency has reportedly been trolling an even more extensive set of phone call data than the NSA. On the other hand, it is likely that the impetus for some of the ongoing surveillance programs is the ongoing armed conflict. Thus, it is possible that the cessation of war might lead to reduced surveillance.

But it is just as likely that the war’s end will lead to greater surveillance. If we forgo the tools of war but continue to confront a threat of terrorism, intelligence will become even more critical. As we have seen, the end of war means that the government would no longer be empowered to take action against suspected terrorists based solely on their status as members of a group, and would instead have to develop specific evidence that they had committed a crime. That need may well put an even higher premium on surveillance.

The principal challenge that surveillance poses stems not from the pressures of war, however, but from the exigencies of the digital age. Before computers, if the government wanted to know what books we were reading, what products we had purchased, what we said in our correspondence with others, with whom we associated, and where we went, it would have had to either obtain a search warrant or spend considerable resources following us. It could not do that to large numbers of people, both because searches require specific showings of probable cause and because it would simply be too costly.

Today, by contrast, virtually everything we do leaves a digital trace that is easily accessed, collected, and analyzed. The books we download or purchase with a credit card, the newspapers and magazines we read online, the e-mails we send, the documents we store in “the cloud,” the places we go while carrying cell phones or GPS devices—all of this is recorded digitally. The Supreme Court has ruled that we do not have any expectation of privacy with respect to information we share with a third party—which includes phone companies, banks, credit card companies, and Internet service providers. As a result, the government can constitutionally obtain such information from those “third parties” without having any basis for suspecting anyone of any crime. And technology has made it cheap and efficient to collect and analyze vast amounts of such data—giving new meaning to the term “dragnet search.”

This will still be true when the war is declared over. Nevertheless, the end of the war may make it more possible to engage in the reasoned public debate necessary to decide to what extent and how our private information should be protected from government oversight.

Another persistent feature of the war has been the absence of transparency and accountability. Virtually all of the United States’ most controversial initiatives were begun under cover of secrecy, and only revealed because someone leaked their existence to the press. This is true of the CIA’s black sites, the use of torture and cruel treatment to interrogate suspects, the drone program, and the NSA’s electronic surveillance.

In wartime, there is understandably greater need for secrecy. But as the war winds down, that need should diminish. In addition, admitting wrongs inflicted on one’s enemy is extraordinarily difficult while the combat rages. It may be somewhat easier afterward. As the fog of war lifts, we may relearn the importance of transparency and accountability.

Indeed, some encouraging efforts to achieve accountability have already begun. The Washington-based Constitution Project, a private group, established a blue-ribbon, bipartisan task force to examine and assess our treatment of war detainees. In April 2013, it issued a persuasive five-hundred-page report unanimously concluding that “it is undisputable that the United States engaged in the practice of torture,” and that “the nation’s most senior officials…bear ultimate responsibility for allowing and contributing to the spread of illegal and improper interrogation techniques.” The task force also found that there was “no firm or persuasive evidence” that the use of harsh interrogation tactics “produced significant information of value.”

The task force did not have access to classified evidence. The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence does have such access. It has conducted an even more extensive investigation of the same subject, culminating in a six-thousand-page report that is likely the most thorough examination of the interrogation program yet (and probably ever). There’s one hitch: the report is not public. Because it was based on classified intelligence, substantial parts of it are likely to remain secret for some time. But with the war’s end, the Senate committee and the Obama administration should press the CIA to declassify as much of the report as possible. If the nation is to learn from the mistakes made in the wake of September 11, it is essential that as much of the report as possible be made public.

6.

The ultimate question in assessing whether President Obama can end the war with al-Qaeda is whether the nation will stand behind him. The American people have long favored withdrawal of our armed forces from Iraq and Afghanistan and showed very little inclination for military intervention in Syria. But because the conflict with al-Qaeda, once we are out of Afghanistan, is likely to be fought principally with drones, it is less clear that Americans will press for its termination. Polls consistently report that Americans favor the drone program—at least as long as it’s not directed at themselves.

Is the country ready to resume a peacetime response to terrorism? Joseph Margulies’s eloquent new book, What Changed When Everything Changed: 9/11 and the Making of National Identity, provides helpful guidance. Margulies, a professor at Northwestern Law School and an eminent Guantánamo habeas lawyer, views our response to September 11 as an ongoing struggle over the meaning of what he calls “the American Creed.” By this, he means the core commitments that define us as a nation—to liberty, equality, democracy, checks and balances, and the rule of law.

Margulies acknowledges that the meaning of these terms is subject to considerable debate. In his more pessimistic moments, he contends that the values are so malleable that they do not actually constrain or guide our conduct at all. Instead, he argues, we simply reinterpret them to conform to whatever “social arrangement” we prefer at a given time. But his own nuanced account of the decade since September 11 shows that in fact the nation’s response was shaped in considerable part by the American Creed. Those who openly preach against Islam itself have remained marginalized; their messages conflict with the nation’s commitment to religious toleration. Senator John McCain successfully challenged the CIA’s use of torture and cruel interrogation tactics by insisting that “this isn’t about who they are. This is about who we are. These are the values that distinguish us from our enemies, and we can never, never allow our enemies to take those values away.” And President Bush’s claims of unilateral executive power were largely rejected because they were at odds with commitments to the rule of law and divided power.

Almost as if he had read Margulies’s book, President Obama’s NDU speech similarly appealed to the “founding documents that defined who we are as Americans, and served as our compass through every type of change.” He is right as a strategic matter to frame the argument in that fashion, and correct as a substantive matter that ending the war would be consistent with those values. But both sides can play this game. Bush and Cheney sought to invoke American values of strength, independence, and liberty, and their supporters continue to beat the drums of war, loudly condemning efforts to use the criminal process instead of military force against terrorists.

In polling data about torture and Islam, and in Congress’s opposition to the closing of Guantánamo, Margulies sees troubling signs that the party of perpetual war is in the resurgence. I am not so sure. Widespread public and congressional skepticism suggests that Americans may be tired of war. But Margulies is certainly correct that the dispute over how to respond to terror is ongoing, and ultimately is about nothing less than what constitutes us as a nation.

This Issue

November 7, 2013

Love in the Gardens

Gambling with Civilization

On Reading Proust

-

1

See “Terror: The Hidden Source,” The New York Review, October 24, 2013. ↩

-

2

Scott Shane, “Debate Aside, Number of Drone Strikes Drops Sharply,” The New York Times, May 21, 2013. ↩

-

3

See Mark Bowden, “The Killing Machines: How to Think About Drones,” The Atlantic, September 2013. ↩