In April 2014 I received a letter from the University of Tehran, inviting me to deliver the keynote address to the first Iranian Shakespeare Congress.

Instantly, I decided to go. I had dreamed of visiting Iran for a very long time. Many years ago, when I was a student at Cambridge, I came across a book of pictures of Achaemenid art, the art of the age of Cyrus and Darius and Xerxes. Struck by the elegance, sophistication, and strangeness of what I saw, I took the train to London and in the British Museum stood staring in wonder at fluted, horn-shaped drinking vessels, griffin-headed bracelets, a tiny gold chariot drawn by four exquisite gold horses, and other implausible survivals from the vanished Persian world.

The culture that produced the objects on display at once tantalized and eluded me. A Cambridge friend recommended that I read an old travelogue about Persia. (I had completely forgotten the name and author of this marvelous book, forgotten even that I had read it, until the great travel writer Colin Thubron very recently commended it to me: Robert Byron’s The Road to Oxiana, published in 1937.) Byron’s sharp-eyed, richly evocative descriptions of Islamic as well as ancient sites in Iran filled me with a longing to see with my own eyes the land where such a complex civilization had flourished.

In the mid-1960s, this desire of mine could have been easily satisfied. Some fellow students invited me to do what many others had been doing on summer vacations: pooling funds to buy a used VW bus and driving across Persia and Afghanistan and then, skirting the tribal territories, descending through the Khyber Pass into Pakistan and on to India. But for one reason or another, I decided to put it off—after all, I told myself, there would always be another occasion.

By the time the letter arrived inviting me to Tehran, it was difficult fully to conjure up the old dream. I knew from Iranian acquaintances that, notwithstanding some highly sophisticated and justly praised films—many of them shown only abroad—censorship of all media in Iran is rampant and draconian. Spies, some self-appointed and others professional, sit in on lectures and in classrooms, making sure that nothing is said that violates the official line.

Support for basic civil liberties, advocating women’s rights or the rights of gays and lesbians, an interest in free expression, and the most tempered and moderate skepticism about the tenets of religious orthodoxy are enough to trigger denunciations and arouse the ire of the authorities. Iranian exiles have detailed entirely credible horror stories of their treatment—pressure, intimidation, imprisonment, and in some cases torture—at the hands of the Islamic Republic. A small number of aid organizations, such as the Scholars at Risk Network and the Scholar Rescue Fund, have struggled tirelessly, though with painfully limited financial resources, to help the victims escape from imminent danger and begin to put their lives together again.

If I went to the Iranian Shakespeare Congress, it would not be with the pretense that our situations were comparable or that our underlying values and beliefs were identical. Sharing an interest in Shakespeare counts for something, as a warm and encouraging phone call from the principal organizer amply demonstrated, but it does not magically erase all differences. A simple check online showed me that one of the scholars who signed my letter of invitation had written, in addition to essays on “The Contradictory Nature of the Ghost in Hamlet” and “The Aesthetic Response: The Reader in Macbeth,” many articles about the “gory diabolical adventurism” of international Zionism. “The tentacles of Zionist imperialism,” he wrote, “are by slow gradation spread over [the world].” “A precocious smile of satisfaction breaks upon the ugly face of Zionism.” “The Zionist labyrinthine corridors are so numerous that their footprints and their agents are scattered everywhere.”

Did my prospective host—someone who had presumably grappled with the humane complexity of Shakespeare’s tragedies—actually believe these fantasies reminiscent of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion? Was he simply trying to get ahead any way that he could, or did he really think, as he wrote, that “Washington is under the diabolical spell of the Zionists” and that “every step they take is in fact weighed and decided by the Zionist lobby within the US ruling system, and as the Persian saying goes, they are not even allowed to drink water without their [Zionists’] permission”?

If I were to ask him directly—which I did not propose to do—I assume he would distinguish, as the Iranian government does, between Zionists and Jews. But why should I confidently expect that this distinction would actually hold? True, he did not know that, as an eleven-year-old at Camp Tevya, in the New Hampshire woods, I fervently sang “Hatikvah.” But from my writing he had to be aware that I was Jewish, and he could have easily learned from my acknowledgments that I have frequently visited Israel, lecturing at its universities and collaborating with its scholars. What did it mean then that he was sending a letter of invitation to me, of all people?

Advertisement

Just after the revolution, the leader of the Iranian Jewish community, Habib Elghanian, was arrested on charges of “contacts with Israel and Zionism,” “friendship with the enemies of God,” and “warring with God and his emissaries.” Elghanian was executed by firing squad. Following this execution, large numbers of Iranian Jews emigrated, and those who stayed are mindful of the fact that “contacts with Israel and Zionism” remain a serious offense. Foreign travelers with any evidence in their passports of visiting Israel are denied admission to Iran. Yet in my case, Shakespeare, it seemed, somehow erased the offense and bridged the huge chasm between us.

Perhaps there was no bridge at all: the invitation was signed by more than one person, and I considered the possibility that there were different positions among the organizing committee and that the more hard-line members had signed off on the invitation in the belief that I would never come or, alternatively, that I would never receive a visa. As it happened, though I was invited in April and duly submitted my visa application, I heard nothing from the Iranian authorities. Months passed. I had almost given up hope and then in November, the day before my scheduled flight to Tehran, the visa was issued. There was no explanation for the delay.

I found myself then on a Lufthansa jet listening to an announcement, just before we touched down at Imam Khomeini Airport, reminding all female passengers that in the Islamic Republic wearing the hijab—the headscarf—was not a custom; it was the law. “Women on board,” the flight attendant put it, “must understand that it is in their interest to put on a scarf before they leave the plane.” And there, waiting for me when I deplaned at 1:00 AM, was none other than the author of the articles denouncing the secret Zionist investors who controlled the world. He was smiling, gregarious, urbane. Quickly establishing our shared interest in movies, we chatted happily about Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon, Ermanno Olmi’s The Tree of Wooden Clogs, and the 1957 classic western 3:10 to Yuma.

We drove into town, past the omnipresent billboards of Ayatollah Khomeini and of the current Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei. It was well after two when we reached the hotel, a former Sheraton rechristened (if that is the right word) the Homa. Though I knew that the conference would begin first thing in the morning, I found myself too wound up to sleep. I lay in bed staring up at an aluminum arrow embedded in the ceiling to show the direction of Mecca. I was anxious about the keynote I was scheduled to deliver. I did not want to stage a provocation: I was less concerned for myself than I was for the organizing committee and the students, since I presumed it would be they who would bear the consequences. But at the same time I did not want to let the occasion simply slip away without somehow grappling with what it meant.

I entered a hall filled with eager faces—everyone rose and applauded as I walked down the aisle. Many held up their phones and took pictures. All the women, of course, wore hijabs; some of them wore chadors. The young men were casually dressed; the faculty wore jackets without ties. I also noticed among the men a few who stood apart and did not seem to be either students or faculty. It was not difficult to imagine who these might be. There was a long prayer, accompanied by a video featuring soft-focus flowers and dramatic landscapes, and then the national anthem, followed by an implausibly long succession of introductions. I felt weirdly nervous as I got up to give my talk.

What did it mean that Shakespeare was the magic carpet that had carried me to Iran? For more than four centuries now he has served as a crucial link across the boundaries that divide cultures, ideologies, religions, nations, and all the other ways in which humans define and demarcate their identities. The differences, of course, remain—Shakespeare cannot simply erase them—and yet he offers the opportunity for what he called “atonement.” He used the word in the special sense, no longer current, of “at-one-ment,” a bringing together in shared dialogue of those who have been for too long opposed and apart.

Advertisement

It was the project of many in my generation of Shakespeare scholars to treat this dialogue with relentless skepticism, to disclose the ideological interests it at once served and concealed, to burrow into works’ original settings, and to explore the very different settings in which they are now received. We wanted to identify, as it were, the secret police lurking in their theater or in the printing house. All well and good: it has been exciting work and has sustained me and my contemporaries for many decades. But we have almost completely neglected to inquire how Shakespeare managed to make his work a place in which we can all meet.

This was the question with which I began. The simple answer, I said, is encapsulated in the word “genius,” the quality he shares with the poets—Hafez, for example, or Rumi—who are venerated in Iran. But the word “genius” does not convey much beyond extravagant admiration. I proposed to my audience that we get slightly closer perhaps with Ben Jonson’s observation that Shakespeare was “honest, and of an open and free nature; had an excellent fancy, brave notions, and gentle expressions.”

Jonson’s praise of Shakespeare’s imaginative and verbal powers—his fancy, his notions, and his expressions—is familiar enough and, of course, perfectly just. But I proposed to focus for a moment on terms that seem at first more like a personality assessment: “honest, and of an open and free nature.” That assessment, I suggested, was also and inescapably a political one. Here is how I continued:

Late-sixteenth- and early-seventeenth- century England was a closed and decidedly unfree society, one in which it was extremely dangerous to be honest in the expression of one’s innermost thoughts. Government spies carefully watched public spaces, such as taverns and inns, and took note of what they heard. Views that ran counter to the official line of the Tudor and Stuart state or that violated the orthodoxy of the Christian church authorities were frequently denounced and could lead to terrible consequences. An agent of the police recorded the playwright Christopher Marlowe’s scandalously anti-Christian opinions and filed a report, for the queen of England was also head of the church. Marlowe was eventually murdered by members of the Elizabethan security service, though they disguised the murder as a tavern brawl. Along the way, Marlowe’s roommate, the playwright Thomas Kyd, was questioned under torture so severe that he died shortly after.

To be honest, open, and free in such a world was a rare achievement. We could say it would have been possible, even easy, for someone whose views of state and church happened to correspond perfectly to the official views, and it has certainly been persuasively argued that Shakespeare’s plays often reflect what has been called the Elizabethan world-picture. They depict a hierarchical society in which noble blood counts for a great deal, the many-headed multitude is easily swayed in irrational directions, and respect for order and degree seems paramount.

But it is difficult then to explain quite a few moments in his work. Take, for example, the scene in which Claudius, who has secretly murdered the legitimate king of Denmark and seized his throne, declares, in the face of a popular uprising, that “There’s such divinity doth hedge a king/That treason can but peep to what it would.” It would have been wildly imprudent, in Elizabethan England, to propose that the invocation of divine protection, so pervasive from the pulpit and in the councils of state, was merely a piece of official rhetoric, designed to shore up whatever regime was in power. But how else could the audience of Hamlet understand this moment? Claudius the poisoner knows that no divinity protected the old king, sleeping in his garden, and that his treason could do much more than peep. His pious words are merely a way to mystify his power and pacify the naive Laertes.

Or take the scene in which King Lear, who has fallen into a desperate and hunted state, encounters the blinded Earl of Gloucester. “A man may see how this world goes with no eyes,” Lear says; “Look with thine ears.” And what, if you listen attentively, will you then “see”?

See how yond justice rails

upon yond simple thief. Hark,

in thine ear. Change places

and, handy-dandy, which is

the justice, which is the thief?

Nothing in the dominant culture of the time encouraged anyone—let alone several thousand random people crowded into the theater—to play the thought experiment of exchanging the places of judge and criminal. No one in his right mind got up in public and declared that the agents of the moral order lusted with the same desires for which they whipped offenders. No one interested in a tranquil, unmolested life said that the robes and furred gowns of the rich hid the vices that showed through the tattered clothes of the poor. Nor did anyone who wanted to remain in safety come forward and declare, as Lear does a moment later, that “a dog’s obeyed in office.”

That Shakespeare was able to articulate such thoughts in public depended in part on the fact that they are the views of a character, and not of the author himself; in part on the fact that the character is represented as having gone mad; in part on the fact that the play King Lear is situated in the ancient past and not in the present. Shakespeare never directly represented living authorities or explicitly expressed his own views on contemporary arguments in state or church. He knew that, though play scripts were read and censored and though the theater was watched, the police were infrequently called to intervene in what appeared on stage, provided that the spectacle prudently avoided blatantly provocative reflections on current events.

Still, such interventions were not unheard of. It is astonishing that in King Lear Shakespeare goes so far as to show a nameless servant rising up to stop his master, the powerful Earl of Cornwall, who is the legitimate coruler of the kingdom, from torturing someone whom he suspects—correctly, as it happens—of treason. “Hold your hand, my lord,” the servant shouts:

I have served you ever since I was a child;

But better service have I never done you

Than now to bid you hold.

The original audience must have been as shocked by this interference as the torturer Cornwall. Though the servant is killed by a sword thrust from behind, it is not before he has fatally wounded his master. And what is most shocking is that the audience is clearly meant to sympathize with the attempt by a nobody to stop the highest authority in the land from doing what everyone knew the state did to traitors. Here there is no cover of presumed madness, and though the setting is still ancient Britain, the circumstances must have seemed unnervingly close to contemporary practice.

How could Shakespeare get away with it? The answer must in part be that Elizabethan and Jacobean society, though oppressive, was not as monolithic in its surveillance or as efficient in its punitive responses as the surviving evidence sometimes makes us think. Shakespeare’s world probably had more diversity of views, more room to breathe, than the official documents imply.

There is, I think, another reason as well, which leads us back to why after four hundred years and across vast social, cultural, and religious differences Shakespeare’s works continue to reach us. He seems to have folded his most subversive perceptions about his particular time and place into a much larger vision of what his characters repeatedly and urgently term their life stories. We are assigned the task of keeping these stories alive, and in doing so we might a find a way, even in difficult circumstances, to be free, honest, and open in talking about our own lives.

My talk took more than an hour, and when I brought it to a close, I expected there to be a rush for the exit. But to my surprise, everyone stayed seated, and there began a question period, a flood of inquiries and challenges stretching out for the better part of another hour. Most of the questions were from students, the majority of them women, whose boldness, critical intelligence, and articulateness startled me. Very few of the faculty and students had traveled outside of Iran, but the questions were, for the most part, in flawless English and extremely well informed. Even while I tried frantically to think of plausible answers, I jotted a few of them down:

In postmodern times, universality has repeatedly been questioned. How should we reconcile Shakespeare’s universality with contemporary theory?

You said that Shakespeare spent his life turning pieces of his consciousness into stories. Don’t we all do this? What distinguishes him?

Considering your works, is it possible to say that you are refining your New Historicist theory when we compare it with Cultural Materialism?

In your Cultural Mobility you write about cultural change, pluralism, and tolerance of differences while in your Renaissance Self-Fashioning you talk about an unfree subject who is the ideological product of the relations of power: Renaissance Self-Fashioning is filled with entrapment theory. How can an individual be an unfree ideological product of the relations of power and also at the same time an agent in the dialectic of cultural change and persistence?

What the questions demonstrated with remarkable eloquence was the way in which Shakespeare functions as a place to think intensely, honestly, and with freedom. “Do you believe,” one of the students asked, “that Bolingbroke’s revolution in Richard II was actually meant to establish a better, more just society or was it finally only a cynical seizure of wealth and power?” “I don’t know,” I answered; “What do you think?” “I think,” the student replied, “that it was merely one group of thugs replacing another.”

2.

And the Iran I had so longed to see, some fifty years ago? My visa permitted me a few days’ stay after the conference, and the principal organizer, an exceptionally kind and hospitable woman, helped me arrange for a car and driver, along with a guide—Americans, I was told, were not permitted to travel unaccompanied. (It was just as well, since I had only learned two or three words of Farsi.) Hussain, the driver, had no English, so I was unable to express directly the admiration I had for the astonishing skill with which he negotiated the insane Tehran traffic.

Hassan, the guide, had at least an uneven smattering of English. He was born, he told me, in the year of the Revolution and did not like to think of what Iran was like before then, when women did not wear the hijab and everyone drank alcohol. (He seemed genuinely shocked when I told him that my wife and I had a glass of wine almost every night with dinner.) At least by the admittedly lax standards to which I am accustomed, he was quite religiously observant. He prayed multiple times a day, often in the “prayer rooms” that are a feature of all hotels and other public buildings. In the mosques he joined the crowds of the faithful who ardently kiss the metal railings around the tombs of the saints and then rub the blessings over their faces. He had a serious cold.

Hussain managed to dodge and feint and bully his way through the vastness of Tehran, most of whose twelve million inhabitants seemed to be on the road. The palatial mansions in the north of the city gave way to seemingly endless miles of office blocks, apartment complexes, factories, shopping malls, and huge army barracks. Hassan warned me not to take pictures of the barracks—I was not inclined to, in any case—or of the huge, sinister Evin prison. There were security cameras, he said, that could detect whether anyone in passing cars was trying to take photographs. Billboards advertising computers, detergent, yogurt, and the like alternated with inspirational images of the Ayatollah Khomeini, political slogans, satirical depictions of Uncle Sam and of Israel, and many, many photographs of “martyrs” from the Iran–Iraq war.

There were martyrs along the avenues, in traffic circles, on the sides of buildings, on the walls around the buildings, on overpasses and pedestrian bridges, everywhere. On the light poles, the martyrs’ images were generally in twos, and the pairings, which may have been accidental, were sometimes striking: a teenager next to a hardened veteran, a raw recruit next to a beribboned high-ranking officer, a bearded fighter next to a sweet-faced young woman.

It took forever to get out of Tehran, but once we crossed the last martyr-festooned overpass, we were suddenly on a highway through an utterly deserted wasteland that extended all the way to Kashan, 150 miles to the south. Kashan is a celebrated carpet city—we had a Kashan rug in our dining room when I was growing up—but my goal was not the crowded bazaar. I wanted to see the late-sixteenth-century Baghe Fin, one of the walled enclosures that in old Persian were called “paradises.” (Other English borrowings from Persian include the words peach, lemon, and orange, along with cummerbund, kaftan, and pajama.) Paradise, in this case, was a relatively small, dusty, square garden with very old cedar trees lined up in rows along very straight paths.

For someone whose taste in gardens runs to Rome’s Doria Pamphili or London’s Kew or New York’s Central Park, so rigid a structure was hard to love, but it made sense against the background of the bleak, parched desert through which we had passed. The crucial feature was water arising from a small nearby natural spring, and for the first time I fully grasped the hyperbolic extravagance of the garden in Genesis, harboring the headwaters of no fewer than four great rivers. The garden in Kashan, emphasizing the pleasures of rationality and control, directed its precious water into straight, narrow channels and a perfectly square pool lined with turquoise tiles. The water also supplied an attached historic hammam, or bathhouse, where a nationalist hero in the nineteenth century was killed by an assassin (another word English has borrowed from Persian).

A twinge of disappointment is built into the fulfillment of any desire that has been deferred for too long, so it is not surprising that my experience of paradise, in the form of the Bagh-e Fin, was a slight letdown. So too Shiraz, the fabled city of nightingales and wine, turned out to have more than its share of traffic and dreary 1970s architecture—and, of course, enormous photographs of the Ayatollah Khomeini and the omnipresent martyrs.

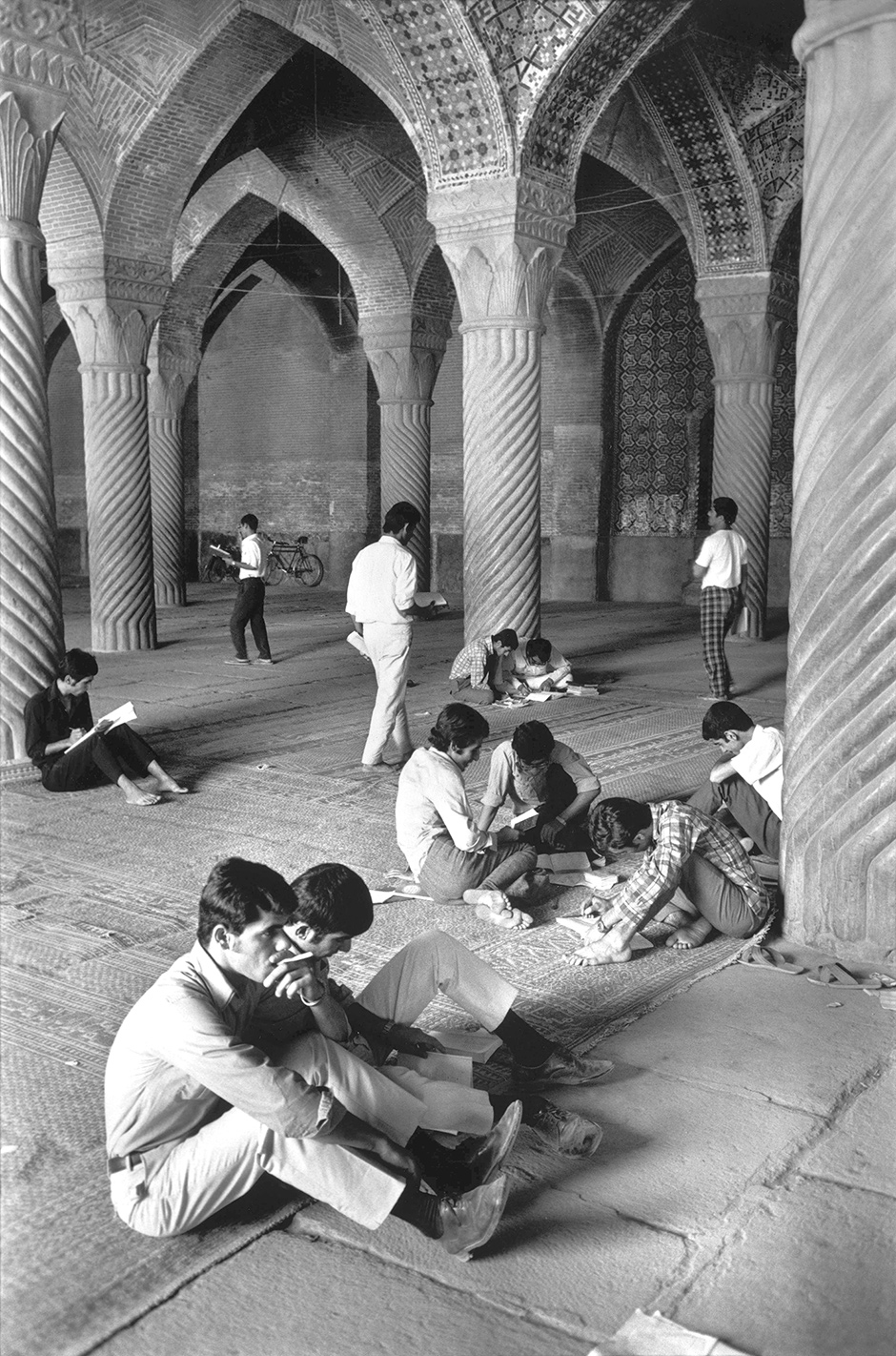

The grand exception to the melancholy that lingered over much of my visit after I left Tehran, and the true fulfillment of my old dream of Iran, was Isfahan. There too, along with a striking absence of tourism, there were the usual grim icons of the Islamic Republic. But the city was largely spared modern architectural depredations. The broad Zayandeh River is spanned by majestic ancient bridges that traditionally featured teahouses. The zealous guardians of morality, fearing that the spaces encouraged the young to flirt with one another, recently shut the teahouses down, but even without them the bridges were full of happy life. And the mosques and gardens and public squares were fantastically beautiful.

Near the close of a long day of sightseeing, Hassan proposed to take me to a church. I thanked him but said that I would be willing to forgo that visit. I was Jewish, and what I would love to see, I told him, was the synagogue that was indicated on my map. He seemed taken aback for a moment, but he quickly recovered and said that in Mashad, the city in which he was raised, he once knew a Jewish family, but they had moved away. We went in search of the synagogue, which seemed from the map to be located on a street adjacent to the city’s labyrinthine covered bazaar, but we did not find it. Hassan began to ask shopkeepers and passersby who looked at us quizzically but were unable to help. As we ventured further into a quiet neighborhood—the bazaar had given way to narrow lanes—he knocked on doors and shouted the question up to shuttered windows. Finally, an old lady said that there had once been Jews who had lived in that area, but they were all gone now. She did not know what had happened to the synagogue.

I do not imagine that there was much I would have seen, certainly nothing comparable to the palaces and madrasas, the hammams and the mosques around me. The most beautiful of all was the mosque of Sheikh Lotfollah, on one side of the immense central square where Persian nobles once played polo. The mosque’s dome is surprisingly off-center from its elaborate entrance portal, so that you reach the sanctuary by passing through a narrow, winding hallway. I gazed in astonishment at the swirling color of the glazed tiles, their turquoise, green, and ochre drawn into magical patterns of intertwining foliage, elegant arabesques, and kaleidoscopic lozenges. Each of the niches formed by the supporting arches was surrounded by cobalt-blue tiles bearing Koranic verses in the Arabic script that seems to me the most beautiful of all written languages.

I looked up into the dome where I saw suspended from its highest point a magnificent, shimmering gold chandelier. It was only slowly that I realized that there was no chandelier there at all; the gold tiles in the dome were picking up and reflecting the natural light from the sixteen windows that circled its base. For once there was another tourist in the space with me, and I walked over to share my sense of wonderment at what we were witnessing. He was a young, very tall, very thin Dutchman, and we chatted while we both tried to capture the magical effect with our cameras. He had, he told me, quit his job in a bank in Amsterdam and had biked to Iran all the way from Holland. He hoped, he said, to make it to Pakistan. This was a level of adventurousness far beyond anything I had imagined for myself in the 1960s, and I was happy to bequeath to him, so much braver or more reckless than I, the last vestiges of the dream of an honest, free, and wide-open world that I had once cherished and that Shakespeare continues to embody.

This article will appear in a different form in the forthcoming Shakespeare in Our Time: A Shakespeare Association of America Collection, edited by Dympha Callaghan and Suzanne Gossett (London: Bloomsbury Arden Shakespeare Publishing Plc, 2016).