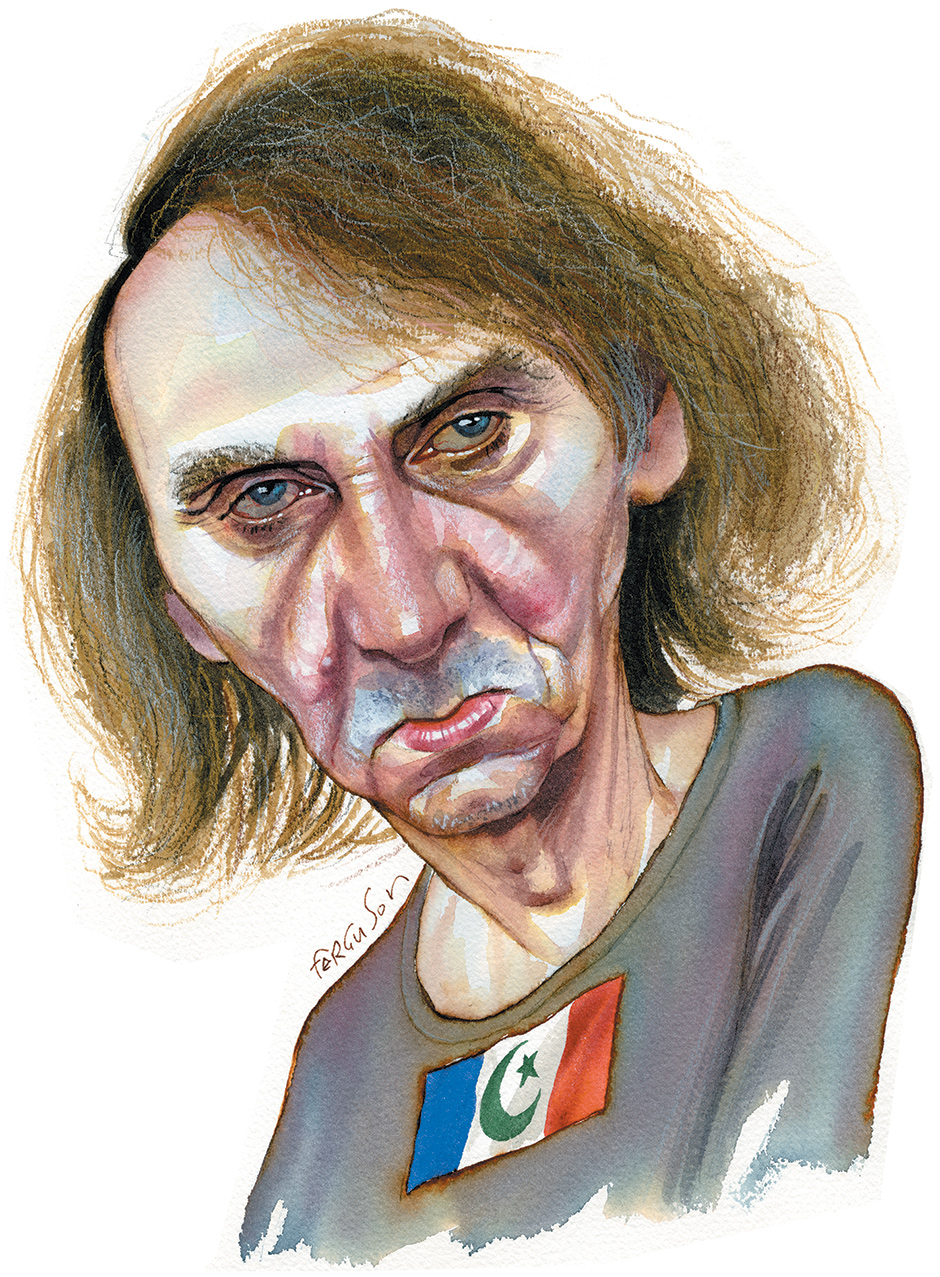

The best-selling novel in Europe today, Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission, is about an Islamic political party coming peacefully to power in France. Its publication was announced this past fall in an atmosphere that was already tense. In May a young French Muslim committed a massacre at a Belgian Jewish museum; in the summer Muslim protesters in Paris shouted “Death to the Jews!” at rallies against the war in Gaza; in the fall stories emerged about hundreds of French young people, many converts, fighting with ISIS in Syria and Iraq; a French captive was then beheaded in Algeria; and random attacks by unstable men shouting “allahu akbar” took place in several cities. Adding to the tension was a very public debate about another best seller, Éric Zemmour’s Le Suicide français, that portrayed Muslims as an imminent threat to the French way of life.1

Zemmour’s succès de scandale ensured that Soumission would be met with hysteria. So was the fact that Houellebecq had gotten into trouble a decade ago for telling an interviewer that whoever created monotheistic religion was a “cretin” and that of all the faiths Islam was “the dumbest.” The normally measured editor of Libération, Laurent Joffrin, declared five days before Soumission appeared that Houellebecq was “keeping a place warm for Marine Le Pen at the Café de Flore.” The reliably dogmatic Edwy Plenel, a former Trotskyist who runs the news site Mediapart, went on television to call on his colleagues, in the name of democracy, to stop writing news articles on Houellebecq—France’s most important contemporary novelist and winner of the Prix Goncourt—effectively erasing him from the picture, Soviet style. Ordinary readers could not get their hands on the book until January 7, the official publication date. I was probably not the only one who bought it that morning and was reading it when the news broke that two French-born Muslim terrorists had just killed twelve people at the offices of Charlie Hebdo.

The irony was beyond anyone’s imagination. And it was doubled by the fact that the cover of the Charlie published that day had a feature mocking Houellebecq as a masturbating drunkard. It was tripled when it was revealed that one of Houellebecq’s close friends, the left-wing economist and Charlie contributor Bernard Maris, was among the victims. (Maris had just published a book, Houellebecq économiste, calling his friend the deepest analyst of life under contemporary capitalism.) Houellebecq appeared on television, devastated, then broke off his publicity tour and disappeared into the countryside. A few hours earlier Prime Minister Manuel Valls, in his first interview after the attacks, felt obliged to say that “France is not Michel Houellebecq. It is not intolerance, hate, and fear.” It is hardly likely that Valls had read his book.

Given all this, it will take a long time for the French to read and appreciate Soumission for the strange and surprising thing that it is. Michel Houellebecq has created a new genre—the dystopian conversion tale. Soumission is not the story some expected of a coup d’état, and no one in it expresses hatred or even contempt of Muslims. It is about a man and a country who through indifference and exhaustion find themselves slouching toward Mecca. There is not even drama here—no clash of spiritual armies, no martyrdom, no final conflagration. Stuff just happens, as in all Houellebecq’s fiction. All one hears at the end is a bone-chilling sigh of collective relief. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come. Whatever.

François, the main character of Soumission, is a mid-level literature professor at the Sorbonne who specializes in the work of the Symbolist novelist J.K. Huysmans. He is, like all Houellebecq’s protagonists, what the French call un pauvre type.2 He lives alone in a modern apartment tower, teaches his courses but has no friends in the university, and returns home to frozen dinners, television, and porn. Most years he manages to pick up a student and start a relationship, which ends when the girl breaks it off over summer vacation with a letter that always begins, “I’ve met someone.”

François is shipwrecked in the present. He doesn’t understand why his students are so eager to get rich, or why journalists and politicians are so hollow, or why everyone, like him, is so alone. He believes that “only literature can give you that sensation of contact with another human spirit,” but no one else cares about it. His sometime girlfriend Myriam genuinely loves him but he can’t respond, and when she leaves to join her parents, who have emigrated to Israel because they feel unsafe in France, all he can think to say is: “There is no Israel for me.” Prostitutes, even when the sex is great, only deepen the hole he is in.

Advertisement

We are in 2022 and a presidential election is about to take place. All the smart money—then as now—is on the National Front’s Marine Le Pen winning the primary, forcing the other parties to form a coalition to stop her. The wild card in all this is a new, moderate Muslim party (the Muslim Brotherhood) that by now attracts about a fifth of the electorate, about as many as the Socialists do. The party’s founder and president, Mohammed Ben Abbes—a cross between Tariq Ramadan and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan before he took power—is a genial man who gets along well with Catholic and Jewish community leaders who share his conservative social views, and also with business types who like his advocacy of economic growth. Foreign heads of state, beginning with the pope, have given him their blessing. Given that Muslims make up at most 6 to 8 percent of the French population, it strains credibility to imagine such a party carrying any weight in ten years’ time. But Houellebecq’s thought experiment is based on a genuine insight: since the far right wants to deport Muslims, conservative politicians look down on them, and the Socialists, who embrace them, want to force them to accept gay marriage, no one party clearly represents their interests.3

François only slowly becomes aware of the drama swirling around him. He hears rumors of armed clashes between radical right-wing nativist groups (which exist in France) and armed radical Islamists, but newspapers worried about rocking the multicultural boat have ceased reporting such things. At a cocktail party he hears gunfire in the distance, but people pretend not to notice and find excuses to leave, so he does too.

As expected, Le Pen wins the presidential primary but the Socialists and the conservative UMP don’t have enough votes between them to defeat her. So they decide to back Ben Abbes in the runoff, and by a small margin France elects its first Muslim president. Ben Abbes decides to let the other parties divide up the ministries, reserving for the Muslim Brotherhood only the education portfolio. He, unlike his coalition partners, understands that a nation’s destiny depends on how well it teaches young people fundamental values and enriches their inner lives. He is not a multiculturalist and admires the strict republican schools that he studied in, and that France abandoned.

Except in the schools, very little seems to happen at first. But over the next months François begins to notice small things, beginning with how women dress. Though the government has established no dress code, he sees fewer skirts and dresses on the street, more baggy pants and shirts that hide the body’s contours. It seems that non-Muslim women have spontaneously adopted the style to escape the sexual marketplace that Houellebecq describes so chillingly in his other novels. Youth crime declines, as does unemployment when women, grateful for new family subsidies, begin to leave the workforce to care for their children.

François thinks he sees a new social model developing before his eyes, inspired by a religion he knows little about, and which he imagines has the polygamous family at its center. Men have different wives for sex, childbearing, and affection; the wives pass through all these stages as they age, but never have to worry about being abandoned. They are always surrounded by their children, who have lots of siblings and feel loved by their parents, who never divorce. François, who lives alone and has lost contact with his parents, is impressed. His fantasy (and perhaps Houellebecq’s) is not really the colonial one of the erotic harem. It is closer to what psychologists call the “family romance.”

The university is a different story. After the Muslim Brotherhood comes to power, François, along with all other non-Islamic teachers, is prematurely retired with a full pension. Satisfied with the money, indifferent, or afraid, the faculty does not protest. A golden crescent is placed atop the Sorbonne gate and pictures of the Kaaba line the walls of the once-grim university offices, now restored with the money of Gulf sheikhs. The Sorbonne, François muses, has reverted to its medieval roots, back to the time of Abelard and Heloïse. The new university president, who replaced the woman professor of gender studies who had presided over the Sorbonne, tries to woo him back with a better job at triple the pay, if he is willing to go through a pro forma conversion. François is polite but has no intention of doing so.

His mind is elsewhere. Since Myriam’s departure he sinks to a level of despair unknown even to him. After passing yet another New Year’s alone he starts sobbing one night, seemingly without reason, and can’t stop. Soon after—ostensibly for research purposes—he decides to spend some time in the Benedictine abbey in southern France where his hero J.K. Huysmans spent his last years after having abandoned his dissolute life in Paris and converted to mystical Catholicism in middle age.4

Advertisement

Houellebecq has said that originally the novel was to concern a man’s struggle, loosely based on Huysmans’s own, to embrace Catholicism after exhausting all the modern world had to offer. It was to be called La Conversion and Islam did not enter in. But he just could not make Catholicism work for him, and François’s experience in the abbey sounds like Houellebecq’s own as a writer, in a comic register. He only lasts two days there because he finds the sermons puerile, sex is taboo, and they won’t let him smoke. And so he heads off to the town of Rocamadour in southwest France, the impressive “citadel of faith” where medieval pilgrims once came to worship before the basilica’s statue of the Black Madonna. François is taken with the statue and keeps returning, not sure quite why, until:

I felt my individuality dissolve.… I was in a strange state. It seemed the Virgin was rising from her base and growing larger in the sky. The baby Jesus seemed ready to detach himself from her, and I felt that all he had to do was raise his right arm and the pagans and idolaters would be destroyed, and the keys of the world restored to him.

But when it is over he chalks the experience up to hypoglycemia and heads back to his hotel for confit de canard and a good night’s sleep. The next day he can’t repeat what happened. After a half hour of sitting he gets cold and heads back to his car to drive home. When he arrives he finds a letter informing him that in his absence his estranged mother had died alone and been buried in a pauper’s grave.

It’s in this state that François happens to run into the university president, Robert Rediger, and finally accepts an invitation to talk. Rediger is Houellebecq’s most imaginative fictional creation so far—part Mephisto, part Grand Inquisitor, part shoe salesman (those look great on you!), his speeches are psychologically brilliant and yet wholly transparent. The name is a macabre joke: it refers to Robert Redeker, a hapless French philosophy teacher who received credible death threats after publishing an article in Le Figaro in 2006 calling Islam a religion of hate, violence, and obscurantism—and who has been living ever since under constant police protection. (Needless to say, no journalists donned “Je suis Robert” buttons to show support for him.) President Rediger is his exact opposite: a smoothie who writes sophistical books defending Islamic doctrine, and has risen in the academic ranks through flattery and influence-peddling. It is his cynicism that, in the end, makes it possible for François to convert.

To set the trap Regider begins with a confession. It turns out that as a student he began on the radical Catholic right, though he spent his time reading Nietzsche rather than the Church Fathers. Secular humanistic Europe disgusted him. In the 1950s it had given up its colonies out of weakness of will, and in the 1960s generated a decadent culture that told people to follow their bliss as free individuals, rather than do their duty, which is to have large, churchgoing families. Unable to reproduce, Europe then opened the gates to large-scale immigration from Muslim countries, Arab and black, and now the streets of French provincial towns looked like souks.

Integrating such people was never in the cards; Islam does not dissolve in water, let alone in atheistic republican schools. If Europe was ever to recover its place in the world, he thought, it would have to drive out these infidels and return to the true Catholic faith. (The websites of French far-right identitaire groups are full of this kind of reasoning, if it can be called that, and the parallels with radical Islamism, which Houellebecq highlights throughout the book, leap out.)

But Rediger took this kind of thinking a step further than Catholic xenophobes do. At a certain point he couldn’t ignore how much the Islamists’ message overlapped with his own. They, too, idealized the life of simple, unquestioning piety and despised modern culture and the Enlightenment that spawned it. They believed in hierarchy within the family, with wives and children there to serve the father. They, like he, hated diversity—especially diversity of opinion—and saw homogeneity and high birthrates as vital signs of civilizational health. And they quivered with the eros of violence. All that separated him from them was that they prayed on rugs and he prayed at an altar. But the more Rediger reflected, the more he had to admit that in truth European and Islamic civilizations were no longer comparable. By all the measures that really mattered, post-Christian Europe was dying and Islam was flourishing. If Europe was to have a future, it would have to be an Islamic one.

So Rediger changed to the winning side. And the victory of the Muslim Brotherhood proved that he was right to. As a former Islam specialist for the secret services also tells François, Ben Abbes is no radical Islamist dreaming of restoring a backward caliphate in the sands of the Levant. He is a modern European without the faults of one, which is why he is successful. His ambition is equal to that of the Emperor Augustus: to unify the great continent again and expand into North Africa, creating a formidable cultural and economic force. After Charlemagne and Napoleon (and Hitler), Ben Abbes would be written into European history as its first peaceful conqueror. The Roman Empire lasted centuries, the Christian one a millennium and a half. In the distant future, historians will see that European modernity was just an insignificant, two-century-long deviation from the eternal ebb and flow of religiously grounded civilizations.

This Spenglerian prophecy leaves François untouched; his concerns are all prosaic, like whether he can choose his wives. Still, something keeps him from submitting. As for Rediger, between sips of a fine Meursault and while his “Hello Kitty”–clad fifteen-year-old wife (one of three) brings in snacks, he goes in for the kill. As forbidden music plays in the background, he defends the Koran by appealing—in a brilliant Houellebecqian touch—to Dominique Aury’s sadomasochistic novel The Story of O.

The lesson of O, he tells François, is exactly the same as that of the Holy Book: that “the summit of human happiness is to be found in absolute submission,” of children to parents, women to men, and men to God. And in return, one receives life back in all its splendor. Because Islam does not, like Christianity, see human beings as pilgrims in an alien, fallen world, it does not see any need to escape it or remake it. The Koran is an immense mystical poem in praise of the God who created the perfect world we find ourselves in, and teaches us how to achieve happiness in it through obedience. Freedom is just another word for wretchedness.

And so François converts, in a short, modest ceremony at the Grande Mosquée de Paris. He does so without joy or sadness. He feels relief, just as he imagines his beloved Huysmans did when he converted to Catholicism. Things would change. He would get his wives and no longer have to worry about sex or love; he would finally be mothered. Children would be an adjustment but he would learn to love them, and they would naturally love their father. Giving up drinking would be more difficult but at least he would get to smoke and screw. So why not? His life is exhausted, and so is Europe’s. It’s time for a new one—any one.

Cultural pessimism is as old as human culture and has a long history in Europe. Hesiod thought that he was living in the age of iron; Cato the Elder blamed Greek philosophy for corrupting the young; Saint Augustine exposed the pagan decadence responsible for Rome’s collapse; the Protestant reformers felt themselves to be living in the Great Tribulation; French royalists blamed Rousseau and Voltaire for the Revolution; and just about everyone blamed Nietzsche for the two world wars. Though a minor work, Soumission is a classic novel of European cultural pessimism that belongs in whatever category we put books like Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities.

The parallels are enlightening. The protagonists in all three novels witness the collapse of a civilization they are indifferent to, and whose degradation leaves them unmoored. Trapped by history, Mann’s Hans Castorp and Musil’s Ulrich have no means of escape except through transcendence. After listening to unresolvable debates over freedom and submission in his Swiss sanatorium, Hans falls in love with a tubercular Beatrice and has a mystical experience while lost in the snow. Ulrich is a cynical observer of sclerotic Hapsburg Vienna until his estranged sister reenters his life and he begins having intimations of an equally mystical “other condition” for humanity. Houellebecq blocks this vertical escape route for François, whose experience at Rocamadour reads like a parody of Hans’s and Ulrich’s epiphanies, a tragicomic failure to launch. All that’s left is submission to the blind force that history is.

There is no doubt that Houellebecq wants us to see the collapse of modern Europe and the rise of a Muslim one as a tragedy. “It means the end,” he told an interviewer, “of what is, quand même, an ancient civilization.” But does that make Soumission an Islamophobic novel? Does it portray Islam as an evil religion? That depends on what one means by a good religion. The Muslim Brotherhood here has nothing to do with the Sufi mystics or the Persian miniaturists or Rumi’s poetry, which are often mentioned as examples of the “real” Islam that radical Salafism isn’t. Nor is it the imaginary Islam of non-Muslim intellectuals who think of it on analogy with the Catholic Church (as happens in France) or with the inward-looking faiths of Protestantism (as happens in northern Europe and the US). Islam here is an alien and inherently expansive social force, an empire in nuce. It is peaceful, but it has no interest in compromise or in extending the realm of human liberty. It wants to shape better human beings, not freer ones.

Houellebecq’s critics see the novel as anti-Muslim because they assume that individual freedom is the highest human value—and have convinced themselves that the Islamic tradition agrees with them. It does not, and neither does Houellebecq. Islam is not the target of Soumission, whatever Houellebecq thinks of it. It serves as a device to express a very persistent European worry that the single-minded pursuit of freedom—freedom from tradition and authority, freedom to pursue one’s own ends—must inevitably lead to disaster.

His breakout novel, The Elementary Particles, concerned two brothers who suffered unbearable psychic wounds after being abandoned by narcissistic hippy parents who epitomized the Sixties. But with each new novel it becomes clearer that Houellebecq thinks that the crucial historical turning point was much earlier, at the beginning of the Enlightenment. The qualities that Houellebecq projects onto Islam are no different from those that the religious right ever since the French Revolution has attributed to premodern Christendom—strong families, moral education, social order, a sense of place, a meaningful death, and, above all, the will to persist as a culture. And he shows a real understanding of those—from the radical nativist on the far right to radical Islamists—who despise the present and dream of stepping back in history to recover what they imagine was lost.

All Houellebecq’s characters seek escape, usually in sex, now in religion. His fourth novel, The Possibility of an Island, was set in a very distant future when biotechnology has made it possible to commit suicide once life becomes unbearable, and then to be refabricated as a clone with no recollection of our earlier states. That, for Houellebecq, would be the best of all possible worlds: immortality without memory. Europe in 2022 has to find another way to escape the present, and “Islam” just happens to be the name of the next clone.

Despite the extraordinary circumstances in which Soumission was published, and the uses to which it will be put on the French left (Islamophobia!) and right (cultural suicide!), Michel Houellebecq has nothing to say about how European nations should deal with its Muslim citizens or respond to fundamentalist terror. He is not angry, he does not have a program, and he is not shaking his fist at the traitors responsible for France’s suicide, as Éric Zemmour is in his Le Suicide français.

For all Houellebecq’s knowingness about contemporary culture—the way we love, the way we work, the way we die—the focus in his novels is always on the historical longue durée. He appears genuinely to believe that France has, regrettably and irretrievably, lost its sense of self, but not because of immigration or the European Union or globalization. Those are just symptoms of a crisis that was set off two centuries ago when Europeans made a wager on history: that the more they extended human freedom, the happier they would be. For him, that wager has been lost. And so the continent is adrift and susceptible to a much older temptation, to submit to those claiming to speak for God. Who remains as remote and as silent as ever.

—This is the third of three articles.

-

1

See my review of Zemmour’s book in these pages, March 19, 2015. ↩

-

2

On Houellebecq’s earlier work, see my “Night Thoughts,” The New York Review, November 30, 2000. ↩

-

3

As if on cue, though, a small Muslim party, the Union des Démocrates Musulmans Français, has recently been formed and will put up eight candidates in the March departmental elections. ↩

-

4

Huysmans was not alone in this. In the decades before and after World War I there was an epidemic of conversions and returns to Catholicism among French writers and intellectuals: Jacques and Raïssa Maritain, Charles Péguy, Max Jacob, Francis Jammes, Pierre Réverdy, and Gabriel Marcel, among others. ↩