Throughout December, the US and some of its allies along with the Bashar al-Assad regime in Damascus stepped up their bombing campaign against the ISIS stronghold in the city of Raqqa, in northern Syria (although 97 percent of air strikes in Syria were carried out by the US). Along with the US, those engaged in bombing include the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Western countries such as Britain, France, and Australia that are also part of the US coalition against ISIS—“Operation Inherent Resolve”—are only willing to take part in strikes in Iraq. Other countries are helping in more limited ways and are sending military and other supplies. </p?

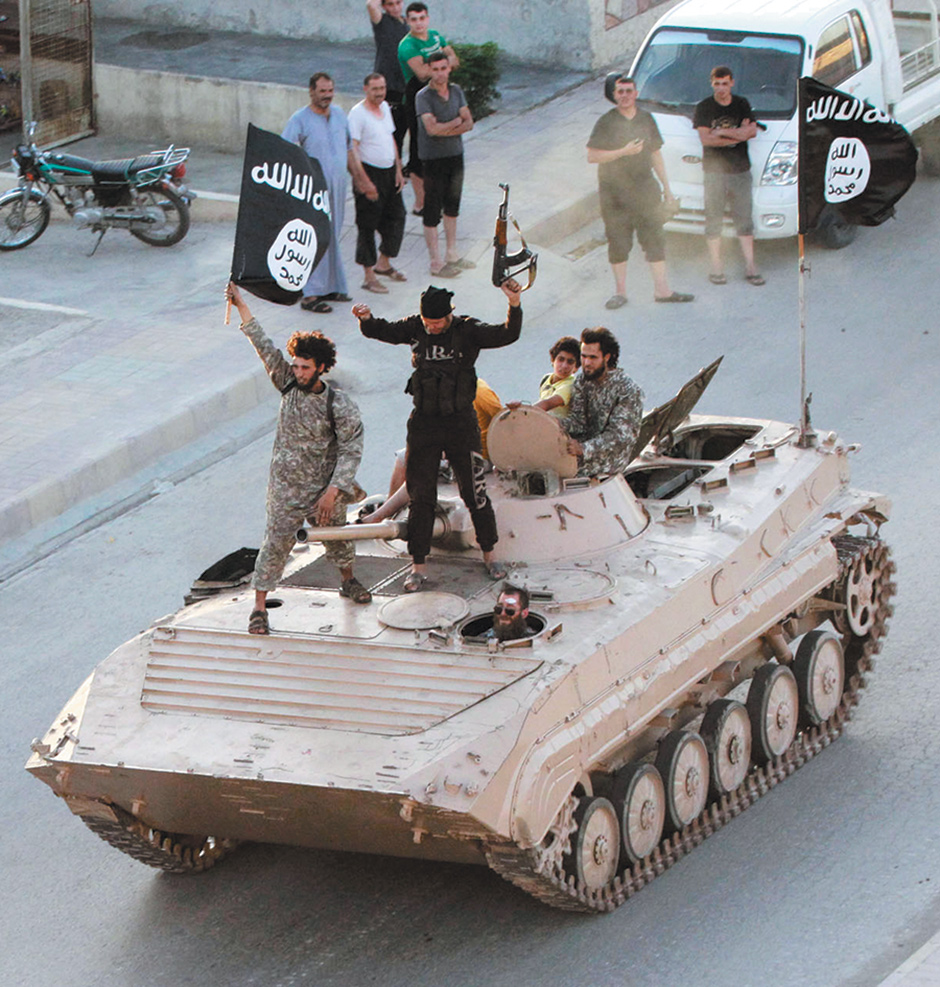

The jihadist organization has long been secretive about where its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and other senior members are based—locals say they move around between Iraq and Syria—but Raqqa is usually referred to as the “capital” of ISIS’s self-declared caliphate, the city most identified with it. To judge from images distributed by the group, Raqqa is at once a utopian Islamic state and an extremist hotbed whose inhabitants crave a radical version of Islam, enjoy public executions, and fervently support their ruthless black-clad overlords. The beheading of the American journalist James Foley—and of several other hostages—was filmed on a hill on its outskirts.

In its statements, ISIS claims that such executions of American and British victims are revenge for the American bombing of ISIS in Syria. Like many of ISIS’s acts, they are a gruesome attempt to project its power and horrify the West. Yet there is little about this provincial center with a population of, according to different estimates, between 250,000 and 500,000 people that might have suggested such jihadist or even Islamist tendencies. In fact, Raqqa did not even become engaged in the Syrian conflict until 2013.

Living in Damascus before the war, I visited Raqqa on several occasions, and I was struck by how ordinary it was. A dusty place far from the country’s other major cities, it offered few amenities and most Syrians I knew complained about it, if they chanced to visit. It was true that the local population, a mixture of tribes and settled Bedouins, was almost entirely Sunni Muslim, but unlike such western Syrian cities as Hama and Aleppo, it didn’t have a tradition of Islamist activism. As a resident of al-Tabqa, a town near Raqqa with an air base that was captured by ISIS in August, put it: “The irony is we were famous for not praying!”

But Raqqa’s relative lack of importance to the Syrian regime—which led to it ceding control of the city—its substantial size, its proximity to Iraq, and its relative distance from the main front lines have been critical to ISIS and its aim of creating a large and highly centralized state. Its forces, after intensive bombing attacks on them and their bases and equipment, have been pushed back from Kobane on the Syrian–Turkish border, but they have gained or consolidated their grip on territory elsewhere including at Heet and Ramadi in Iraq, and they still have firm control of Raqqa.

Since ISIS took over Mosul, Iraq’s second-biggest city, on June 10, some analysts think that it has become the group’s new capital—after all, ISIS is at heart an Iraqi organization, having grown out of al-Qaeda in Iraq, and almost all its top leaders, including Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, are Iraqi. But in Mosul, which has a population of more than a million people, there is still a degree of power-sharing with other Sunni groups, including former Baathists from Saddam Hussein’s regime and some tribesmen. In Iraq ISIS faces more military threats than in Syria—from Shia militias, the Kurdish Peshmerga, the ragtag Iraqi army, and some Sunni tribes, as well as the US-led coalition.

By contrast, even before ISIS gained control of eastern Syria, starting with small villages and towns, then Raqqa in June 2013, and finally the greater territory in June 2014, the Syrian regime had largely abandoned the region to focus on controlling the more populated western areas of the country. It left ISIS mostly undisturbed once the group was in power, since its growth was helpful to Damascus’s efforts to portray the opposition as “terrorists.” Syria’s rebels, who originally took Raqqa from the regime in April 2013, are a hodgepodge of groups, far weaker than ISIS. Although supportive countries such as America, Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia have become more coordinated in their funding of some Syrian rebel groups, those groups are fragmented. The Islamist groups, even those who rely on private donors, are stronger than the more secular American-backed fighters—and even they pale into insignificance when compared to ISIS.

For ISIS’s foreign recruits, the majority of whom have crossed into Syria from southern Turkey (Turkey has since tried to tighten its border), Raqqa is also relatively easy to reach. Although air strikes by America and its Arab allies and the Assad regime’s recent raids have recently made life for ISIS more difficult, the city has become a crucial power center in a territory that is now bigger than many countries and includes some six million to eight million people in Iraq and Syria. “There is still the sense that Raqqa is the capital,” said Sarmad Jilani, a Turkey-based Syrian exile and coordinator of Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently, an activist group that has correspondents in the city.

Advertisement

ISIS occupies several buildings in Raqqa such as the governor’s palace, the municipal building, and the Armenian Catholic Church of the Martyrs, and it wields tight control over areas outside the city such as Division 17, a former army base, and oil installations. Many of these locations have been targeted by US air strikes. And many of the group’s Western and other hostages who were subsequently executed or released for ransom were held in these out-of-town locations. ISIS’s leaders include a number of former Iraqi Baathist military men such as Abu Ali al-Anbari, once a major general under Saddam Hussein, who today is said to be a deputy to al-Baghdadi.

The leaders have constructed a hierarchical, disciplined organization. According to Abu Hamza, a Syrian defector from the group’s intelligence services whom I talked to in southern Turkey this fall, at the top is a group of some twenty men, who have made a division between ISIS’s military and civilian arms. Specific leaders are responsible for ISIS’s military and security forces; there are civilian ministries run by ministers, although they appear not to have physical central locations. Each Syrian province that ISIS controls, Abu Hamza told me, has an emir with military and civilian deputies; they oversee organizing the local administration. The group has set up new courts, local police forces, and an extensive economic administration, while taking over the existing education, health, telecom, and electricity systems (with some utilities still run by the Syrian government).

According to ISIS’s strict interpretation of sharia law, women must wear a niqab, men must not have pictures on their T-shirts, smoking is banned, shops must shut for the five prayer times (as happens in Saudi Arabia), and only women can work in women’s clothing shops. Since August 2014 women need a mahram, a male companion, to go out. Adherence to the rules is monitored by an all-female brigade called al-Khansa and a male Hisbeh force. Two women from the city told me that Saudi members of ISIS, who come from a country with religious police and a version of Islam closest to the ISIS worldview, are often the most vocal about moral transgressions.

Raqqa has also been a model for ISIS’s system of taxation: shopkeepers from Raqqa I talked to in southern Turkey told me the group takes 2.5 percent of their revenue, deemed zakat, the alms payment in Islam, and a monthly fee of 1,500 Syrian pounds (SYP), or roughly $8.30; it is never described as a tax. ISIS now collects around 400 SYP per month for telephone lines, even though the costs are borne by the Assad regime. Locals also report that salaries are regularly paid to both civilian workers and fighters, who get $400 or more per month. In the name of consumer protection, ISIS regulates the price and quality of goods.

All this would have been difficult to imagine as recently as two years ago. Although there had been some protests when the Syrian uprising began in March 2011, the residents of Raqqa had remained fairly loyal to the Assad regime, partly because of Damascus’s patronage of local tribes, partly because the large number of displaced Syrians who came to the city during the opening years of the conflict were not intent on rebellion. In March 2013, however, mainly Islamist rebel militias, including the devout Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra, al-Qaeda’s Syrian branch, seized Raqqa from the Assad regime. The takeover came from outside and many locals were unhappy about this.

When I visited the city two months later, in May 2013, the black flags of Jabhat al-Nusra were hanging along the street close to the governor’s office, which it then occupied, but no single group controlled the city. The militias and rebel groups were keen on gaining support from locals rather than simply imposing their rule; they competed for space with local moderate activists who held workshops about matters such as women’s rights and religious tolerance and pushed for elected local bodies such as the city council.

I could still be aware of the tolerant outlook Syria had been known for; for example, I met an Alawite nurse who was open about her sect although the Alawite minority in Raqqa was closely associated with the Assad regime. (In Raqqa today, she would be beheaded just for her sect.) Locals who were keen to make sure the city continued to function set up a municipal council headed by a lawyer, and it was having considerable success keeping city services going, ensuring that street cleaners were paid, and maintaining an ambulance system. Many young people reveled in their newfound freedom from control by the Assad regime. Graffiti and art projects were everywhere.

Advertisement

But competition between armed groups and lack of consistent funding to the council (which came in spurts from foreign countries including France and Qatar) prevented a full-fledged local government from taking shape. This gave ISIS an opportunity to capture a major city and started it on the road to creating a so-called Islamic state.

At the start of Syria’s war, seeing an opportunity, al-Qaeda in Iraq’s leaders had sent a group of jihadists to Syria to create the group that became Jabhat al-Nusra. In April 2013 Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, then leader of the Islamic State in Iraq, al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Iraq, decided to claim the connection and declared that the two groups would merge and be known as ISIS—or the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (Greater Syria). But Jabhat al-Nusra’s leader, Abu Muhammad al-Julani, a Syrian, refused the merger.

Unlike Jabhat al-Nusra, ISIS immediately made clear that its primary aims were not to fight Assad but to hold territory and immediately impose sharia rule, and it was willing to use more brutal tactics—particularly in killing civilians—than al-Qaeda to achieve them. (Al-Qaeda’s central leadership had long criticized its Iraqi affiliate for being too brutal, and after the dispute between Baghdadi and al-Julani, ISIS split from al-Qaeda, leaving Jabhat al-Nusra as the group’s affiliate in Syria.)

In August 2013, ISIS forces launched a brutal attack on other rebel groups in Raqqa, rapidly taking control of the city as the other militias withdrew. Now ISIS controlled a provincial capital rather than just small villages and towns, and it became the group’s de facto headquarters. The details of who directed what are unclear, but the group set up bases in Raqqa, manned by Syrians and Iraqis as well as numerous foreign fighters. More flocked in as the city gained notoriety. They have continued to come since ISIS, renaming itself the Islamic State, declared its “caliphate” after taking Mosul in June 2014.

There is still a question, which preoccupies American officials, of why ISIS has attracted so many fighters—the most rapid mobilization of foreign fighters so far, outstripping recruitment in the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan and the war against Saddam Hussein in Iraq, according to jihadist experts. The answer may lie in part in ISIS’s unprecedented use of social media to attract people, the relative ease of getting to and living in Syria, and coming at a time at which governments in the region and in the West lack convincing ideologies and are seen as corrupt by their inhabitants, Muslim or otherwise.

It is unclear how much support ISIS enjoys in Raqqa, but it is certainly less than in Iraq where disgruntled Sunni groups entered an alliance with ISIS after they were marginalized by the Shia-led government in Baghdad following the fall of Hussein. During the initial phase of ISIS rule, locals told me they disliked the excesses of the Islamic State, but some were pleased that the corruption and chaos of rebel rule by the likes of Ahrar al-Sham as well as by less devout groups had ended. One businessman from Raqqa who now lives in Turkey told me that though he hated the group, it was easier to ship goods through ISIS territory because the checkpoints did not take bribes, as other rebel groups did. Some locals, keen to work with whoever was in power, backed ISIS. The ISIS leaders were also pragmatic in running municipal services in Raqqa, keeping expert employees in position, including in government-run services such as the phone network, but making clear to them that they now work for the Islamic State.

Schoolteachers are allowed to continue to teach, but with an altered curriculum in which such subjects as chemistry and French have been removed and Islamic studies added. A junior doctor in her twenties who went into exile in September told me how the department heads in her hospital in Raqqa had been replaced by Islamic State men—complete with titles such as “emir of general medicine.” Female doctors were now only allowed to treat female patients, and in full niqab. “How am I meant to operate in black gloves and with barely my eyes showing?” the doctor asked me.

It quickly became clear that ISIS’s ability to maintain power depended overwhelmingly on outright repression. Although the beheadings of two American journalists and one aid worker, as well as two British aid workers, have made headlines, far more Syrians and Iraqis have been murdered by the group and scores have been tortured. One UK-based Syrian human rights–monitoring group reckons that ISIS has killed 1,880 people since it declared its caliphate in June. That number includes 1,177 civilians and at least 120 of its own fighters who may have wanted to leave the group.

Abu Hamza, the defector, told me that the will of the state is primarily imposed by security services, just as it was under the Baathist regime in Iraq and continues to be in Assad’s Syria. ISIS’s security forces, he said, are a mix of nationalities but include enough Syrians who know the pasts of fellow Syrians. “They look at all the threats to Islamic State, from Bashar al-Assad to America and the other rebels—but their number one enemy is the rebels,” he said, referring to the many groups operating in Syria, ranging from Ahrar al-Sham to American-backed outfits.

Residents said they were terrified of the group’s horrific punishments. In a central square in Raqqa, heads are posted on spikes with a sign above them indicating what transgression was involved. The square used to be called Sahat al-Naem, or paradise, but is now called Sahat al-Jaheem, or hell; the doctor I met told me she took a route to work that took three times as long just to avoid it.

None of the Raqqans I talked to was sure whether ISIS’s sharia courts actually listen to evidence, but several noted that gruesome punishments are sometimes meted out on the spot to instill fear. A former teacher from Manbij, an ISIS-controlled town northeast of Aleppo, told me, almost in disbelief, how he watched the beheading of a man who had accidentally driven into ISIS territory while smoking and then tried to claim it was not banned in Islam after being caught. Militants then jumped into the man’s car and ran over his head, he told me.

Though ISIS is unable to electronically monitor the phones and Internet controlled by the Syrian regime, the group gathers information about everyone else, does spot checks on phones, beheads anyone caught filming (hence the dearth of images from the city), and has members monitoring goings-on in public places. Many Syrians told me they had deleted photos and music from their phones for fear of being caught.

Months ago people in Raqqa began describing how foreign jihadists were bringing in their families, or marrying Syrian or foreign women—who, like men, have been drawn to ISIS in greater numbers than to any previous jihadist movement. Many have been impressed by the actual setting up of a “caliphate” and some benefits of living there. The Islamic State distributes housing to fighters, and according to some accounts, widows receive welfare benefits based on how many children they have. ISIs sees children as important to ensuring its future. Although parents told me that ISIS does not force children to go to school, it recruits young people under eighteen into its ranks, runs Koranic lessons and events for children, and, parents told me, likes to make sure children witness beheadings and violence so as to get accustomed to it.

Footage filmed by a woman who hid her phone in her niqab showed French women in an Internet café telling their families they would not be coming home. In a city where once neighbor knew neighbor, now many can’t even speak the same language, the doctor told me. “By the time I left I no longer recognized Raqqa as a Syrian town.”

It is unclear where the Islamic State’s videos and English-language magazine Dabiq are created, but residents in Raqqa describe high-tech equipment in the city—local shops sell satellite Internet connections since that is the only way to get online. Abu Hamza told me that an Icelandic filmmaker was among the recruits to the group (Iceland’s government says none of its citizens has joined ISIS), and that he was one of those responsible for the professional videos used to attract new recruits and frighten Western viewers. In one of those videos, the quotations from Dabiq’s fluent articles suggest that the magazine is written and edited by native English speakers. You see, for example, passages discussing speeches by American politicians such as John McCain and, in the latest edition of Dabiq, a discussion of global economics in an article about ISIS’s plans to bring in its own currency.

Despite all this expertise from abroad (Abu Hamza also told me there are Chinese experts on drones and Egyptian hackers, among others), several people from Raqqa said that ISIS is failing at ruling, particularly since air strikes by the US began this fall. A mother of two from the city told me in southern Turkey this autumn that “electricity comes almost never so everyone uses a generator, water is scarce when there is no power for pumps, medical care is worsening, most schools are shut, and rubbish lies on the street.”

American-led air strikes appear to be doing more damage to ISIS’s ability to govern than to its military strength (although it can no longer run convoys across the desert openly without worrying about being hit). The air strikes have hit at least sixteen oil refineries, compromising a main source of funding of the Islamic State—but only in Syria, because the Iraqi government doesn’t want to ruin its oil infrastructure. The people from Raqqa told me that in the days after the first American air strikes ISIS fighters melted back into the population, making them harder to target, but relieving some of the repressive apparatus, such as checkpoints, in the city. Only in the evenings did the group come back out, to tell residents that America’s campaign was a war against Islam.

Some Raqqa residents said that until the US-led air strikes, you were safe if you followed the rules, however perverse, that were posted on walls and circulated quickly by word of mouth. But the air strikes have made ISIS more paranoid and prone to kidnapping people randomly, the women told me. At the same time, some say ISIS’s core Iraqi leadership appears to be trying to entrench the group’s control of the local population by “Syrianizing,” i.e., finding local leaders, as they have done in Iraq.

Abu Hamza, who formerly led ISIS training sessions and joined its intelligence ranks, said that the prospect of getting promoted to positions of responsibility within the group has helped it attract more Syrians—he admitted this had been appealing to him when he joined ISIS. In addition, Jilani, the exile from Raqqa I spoke to in Turkey, told me that since late November when the Assad regime began bombing Raqqa—mainly civilian areas rather than ISIS bases—locals have become more sympathetic to the group, seeing them as the only defense against Damascus.

Many people wonder why those under ISIS rule don’t revolt. After all, Raqqa’s earlier history under the Assad regime and during the initial months of rebel control suggests that much of the city’s native population would be keen to throw off ISIS’s rule—some residents told me it was worse than Assad’s. Moreover, the prospect that the Sunnis will rise up against ISIS is, after air strikes, central to the US strategy. But the people I met from Raqqa said they are too afraid to engage in open opposition. They point out that local protests both against the Assad regime and then, in the months after the group’s takeover of the city, against ISIS ended in massacre. When an estimated seven to nine hundred members of the Shaitat tribe mounted an attack in August against ISIS in Deir Ezzor province, to the east of Raqqa and abutting Iraq, they were slaughtered, but no one paid any attention. Many Raqqans have left and, as foreigners arrive in large numbers to join ISIS, the population of the town is becoming more loyal to ISIS.

The Western-backed opposition, meanwhile, has been eliminated in ISIS-controlled areas and is being snuffed out elsewhere thanks to a lack of support and funds. The US-led coalition’s plan to train vetted Syrian rebels to act as a ground force against ISIS will not start until sometime in 2015 and US officials say it will not be in full effect until 2016.

Syrians rebels, meanwhile, say any support must also allow them to defeat Assad, their original enemy. (Although US officials say Assad is the root of the problem, there is little attention now being paid to his ongoing crimes. And since the US is attempting to strike a nuclear deal with Iran, which has supplied arms and money and trained a paramilitary force for Assad, it is unlikely to want to anger Tehran.)

Some Syrians living under ISIS rule told me they believed that all they could do now was silently resist, much as they had under Assad. They carry on whispered conversations in houses, watch “un-Islamic” television programs at home, put on music as soon as they leave ISIS territory. When I asked a grandmother from Raqqa whose sons had fought with the mainstream rebels whom she would choose between Assad and ISIS if they were the only options left, she said neither—she, like many, has subsequently left the country for good. Abu Hamza, by contrast, said ISIS was rapidly becoming the only option for Sunnis in Syria who didn’t want to reconcile with the regime. ISIS may be failing in its attempt to govern, but for such people there is nothing else in sight.

—January 7, 2015