In the summer of 1874, Claude Monet was living in Argenteuil, a suburb on the Seine some seven miles north of Paris, and Édouard Manet was spending time at his family’s property in nearby Gennevilliers, just across the river. Two paintings made by Manet that summer are the subject of Willibald Sauerländer’s new book, Manet Paints Monet: A Summer in Argenteuil, which Colin B. Bailey reviews in The New York Review’s April 23 issue. Monet’s influence is crucial to what Sauerländer considers to be Manet’s “conversion” to Impressionism. Yet their acquaintance was not always amiable.

We present below a series of paintings by Manet, Monet, and Renoir, with commentary drawn from Bailey’s review.

—The Editors

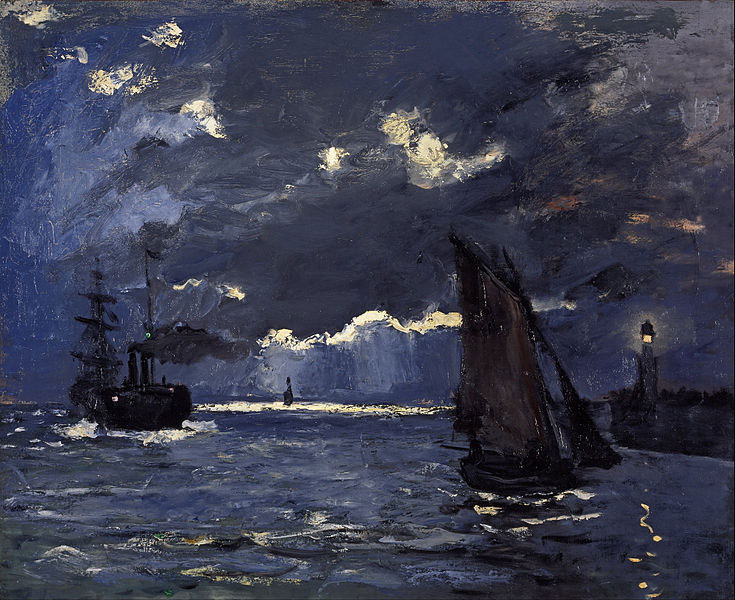

Monet had first crossed Manet’s path at the Salon of 1865, where confusion resulted owing to the regulation of hanging works alphabetically by artists’ names. There Manet showed his highly controversial nude Olympia.

At the Salon, Monet’s two large seascapes had been placed near the older artist’s work, and the Monets were much admired. Infuriated at being congratulated for Monet’s seascapes, Manet apparently exclaimed, “Who is this rascal who pastiches my painting so basely?”

Monet, for his part, was dismissive of Manet’s Woman with a Parrot—Zola considered it the best of his recent paintings—writing to Frédéric Bazille in June 1867 that “La Femme rose is bad, his earlier work is better than what he is doing at the moment.”

Yet there can be no doubt of Manet’s artistic and affective complicity with Monet at Argenteuil in the summer of 1874. Dazzling and virtuosic, Manet’s painting Argenteuil is louche and playful at the same time, with its lusty canotier balancing his companion’s parasol over their adjacent laps, her millinery confection, as T.J. Clark has written, a “wild twist of tulle, piped onto the oval like cream on a cake.” Routinely identified as the “drill sergeant” of the Impressionists—despite his refusal to participate in any of their exhibitions—it is clear that Manet now intended to come out (as it were) and show solidarity with the fledgling avant-garde, including such painters as Monet and Renoir.

The second Argenteuil boating picture, also likely completed in the summer of 1874 but held back until the Salon of 1879, suggests something of a withdrawal from Monet’s shimmering chromatic language.

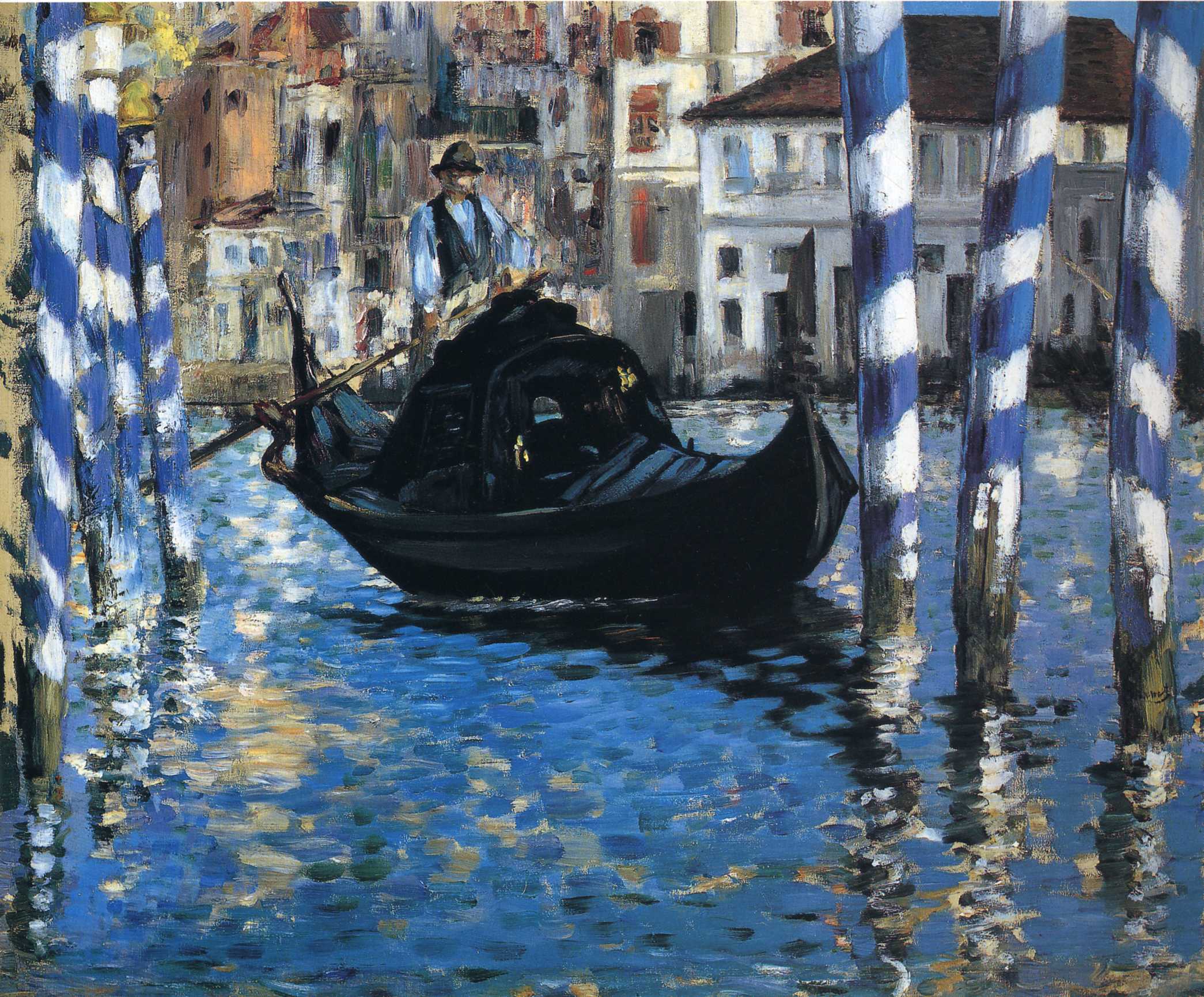

Paradoxically, Manet’s most fully realized Impressionist landscapes—done far from Argenteuil and Monet—are the two dazzling views of Venice’s Grand Canal, painted in Tissot’s company in the autumn of 1875

On July 23, Manet had been invited to paint en plein air in the garden of Monet’s rented villa on the rue Pierre Guienne (a house that Manet had found for him three years earlier). In a vibrating, high-keyed canvas, Manet portrayed Camille Monet and their seven-year-old son Jean seated on the lawn, with Monet in his painter’s smock tending to the flowers behind them. As Sauerländer observes in one of his most endearing insights, a cock, hen, and chick line up in the left foreground, affectionately paraphrasing the family as in an animal fable.

While Manet was at work, Renoir arrived, borrowed paints, brushes, and a canvas from Monet, and executed a vivid close-up of Camille and Jean, joined by the rooster. Irritated by Renoir’s intrusion, Manet is reported to have told Monet, “He has no talent, that boy. Since he’s your friend, you should tell him to give up painting!”