When Martin Gusinde was ordained as a priest in Germany in 1911, he hoped to travel to New Guinea to work as a missionary among exotic tribes. Instead, his superiors sent him to Chile to teach at the German school in Santiago. Within a few years, however, he found his calling at Chile’s Museum of Ethnology and Anthropology, carrying out expeditions to Tierra del Fuego in the far south of Chile and Argentina. Gusinde’s haunting photographs of the Selk’nam, Yamana, and Kawésqar peoples—now collected and published in The Lost Tribes of Tierra del Fuego—present a way of life that was already on the brink of extinction when he visited the region in 1918–1924 and that has since ceased to exist.

Gusinde first went to Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego in December of 1918, filled with (in his own words) “indescribable enthusiasm” and “youthful dreams” of an encounter with archaic tribes. The young Charles Darwin, on his famous voyage to South America in 1832, was shocked by the primitive state of Isla Grande natives: “One can hardly make oneself believe that they are fellow-creatures, and inhabitants of the same world,” he wrote.

Yet when Gusinde arrived in the mission settlement of La Candelária, his illusions were “shattered” and “demolished.” By that time, the once populous Selk’nam (some 4,000 inhabited the region in the 1880s) had been reduced to a few hundred living in poverty around the mission. In addition to the fatal scourge of measles and smallpox that decimated other Amerindian groups, the Selk’nam were singled out in the 1890s for a campaign of genocide: Romanian engineer Julius Popper paid bounties for Selk’nam heads and ears and organized hunting parties to clear them from the territory to make way for miners and ranchers.

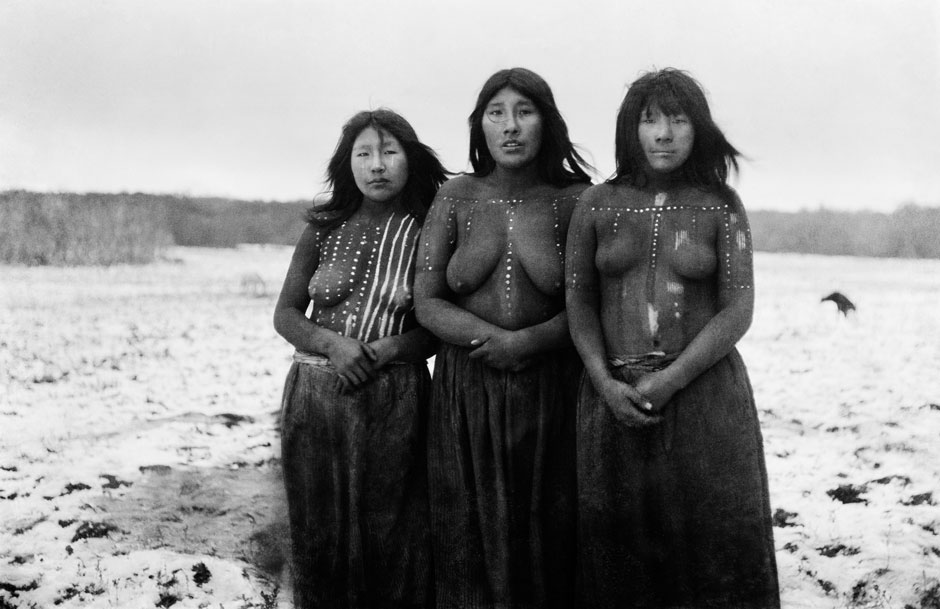

Photography was an important aspect of Gusinde’s scientific and humanistic endeavor, and The Lost Tribes of Tierra del Fuego is the first book to address this aspect of his work in its own right. Comparing his field notes with the 1,200 images preserved in mission archives and digitized by the book’s editors, it became clear that many of his photographs did not so much record daily life and ritual, but rather, reconstructed, recreated, and reenacted traditions that had already been abandoned. “As these people disappear, so does their uniqueness,” he wrote. “The most urgent thing, right now, is to save what is left.”

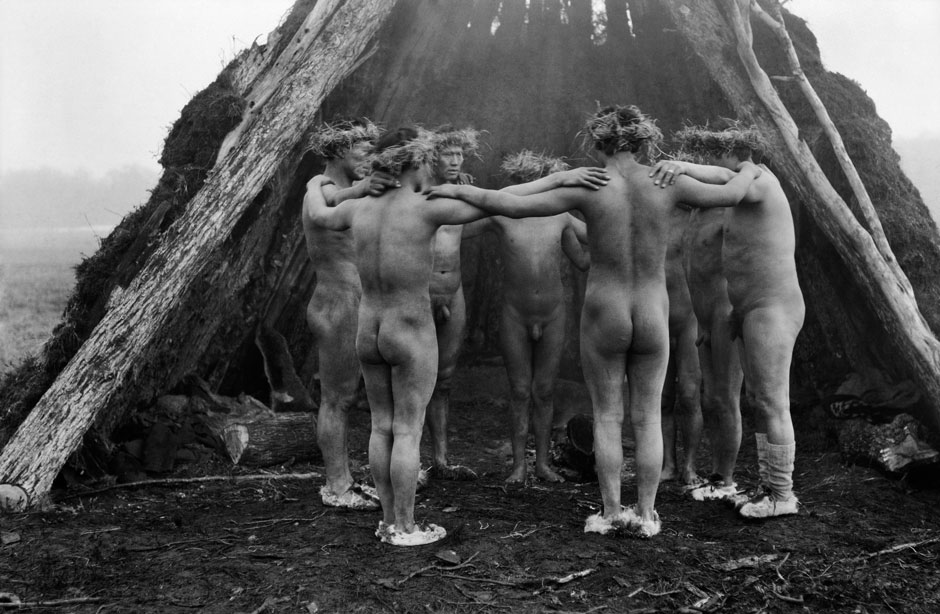

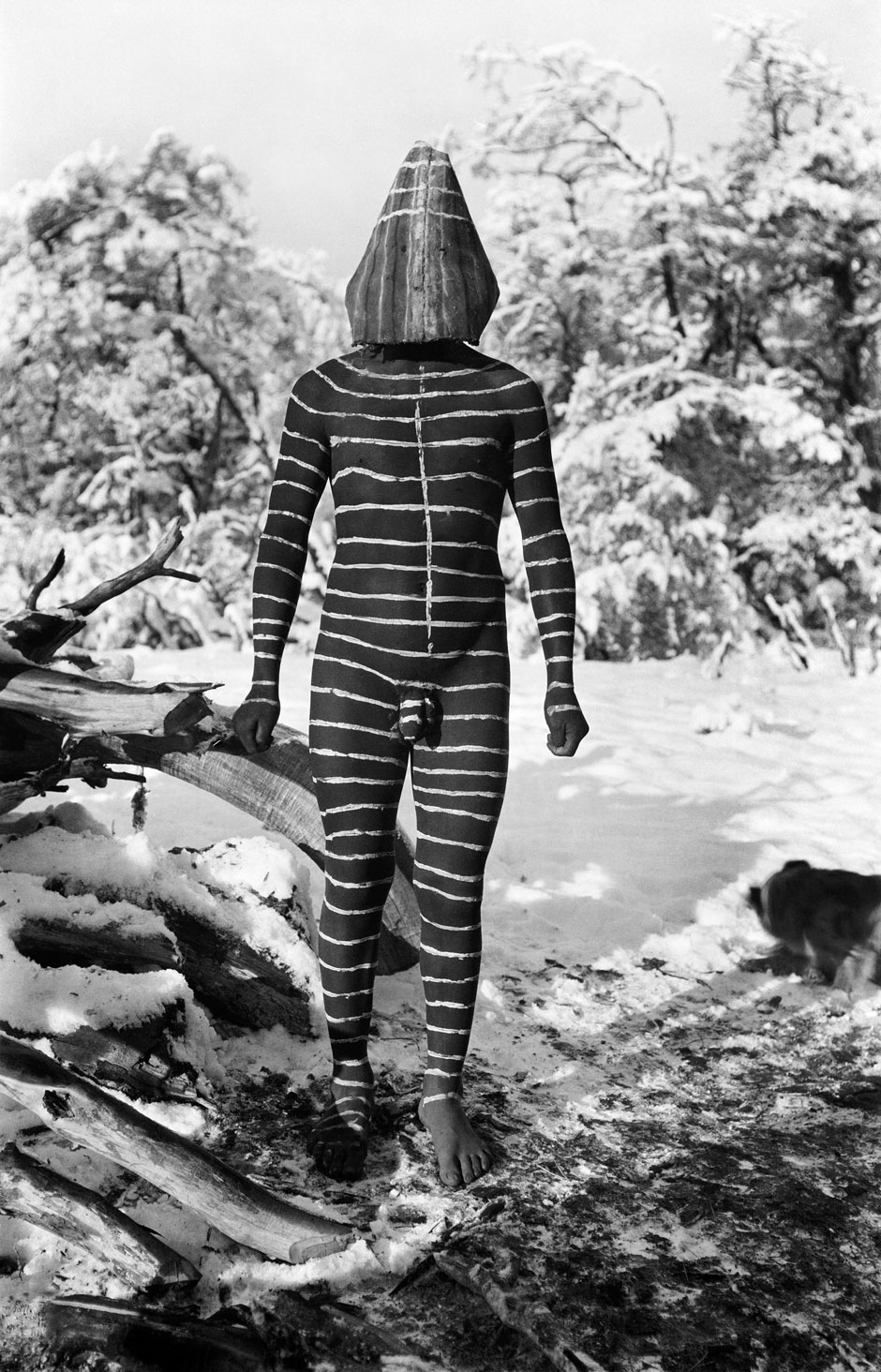

There is something bewitchingly surreal about his photographs of the Hain initiation ceremony, in which young Selk’nam men are hazed by a pantheon of spirits that are revealed, in the final moments (forbidden to women), to be kinsmen in elaborate masks. Several photos show naked male figures standing barefoot in the snow, their bodies painted in bold white stripes on dark ochre and wearing eerie, phallic headdresses. An image of a snowy field strewn with corpse-like forms—according to the caption, initiates enacting a passage through the underworld—evokes uncanny echoes of the actual Selk’nam genocide. White bone-dust covering the skin and conical masks of Kawésqar initiates gives them a spectral, hallucinatory quality.

Another series of photographs depicts traditional Selk’nam clothing, archery, dwellings, and wrestling. Despite their staged, documentary nature, these images stand out nonetheless as intensely intimate and personal, each individual identified by full name and kinship in Gusinde’s detailed field notes, which inform the book’s captions. His portraits especially reveal a tension between Gusinde’s ethnographic training and his humanistic (and artistic) instincts. A few sad photos demonstrate the poverty of these peoples’ contemporary lives in shacks around missions.

Gusinde was one of the first twentieth-century ethnographers to break with the tradition of detached observation and identify personally with the societies he studied: he himself was initiated into the secretive Selk’nam and Yamana rites of manhood. In 1923 he photographed the last Hain ritual before the Selk’nam were decimated by a final wave of measles and forced to assimilate.

The last fluent Selk’nam speakers died in the 1980s, and Herminia Vera, who spoke the language as a child, lived until 2014: at ninety-one, she was born the same year Gusinde photographed the final Hain ceremony documented in this book. But Joubert Yanten, a linguistically talented mestizo man, has sought to encourage a cultural revival. When he discovered as a teenager that he was descended from the Selk’nam, he set out to learn the language. Adopting the tribal name Keyuk, he studied a 1915 lexicon and listened to recordings made by anthropologist Anne Chapman in the 1970s. Now Keyuk is a media star in Chile, composing lyrics in Selk’nam and performing with an “ethno-electronic” band.

In a recent interview with The New Yorker Keyuk explains the etymology of the group’s name: “The word ‘Selk’nam’ can mean ‘We are equal,’… though it can also mean ‘we are separate.’” Gusinde’s camera captures the essence of this fundamental enigma of the ethnographic encounter.

Advertisement

The Lost Tribes of Tierra Del Fuego is published in English by Thames & Hudson, and in French and Spanish by Editions Xavier Barral.