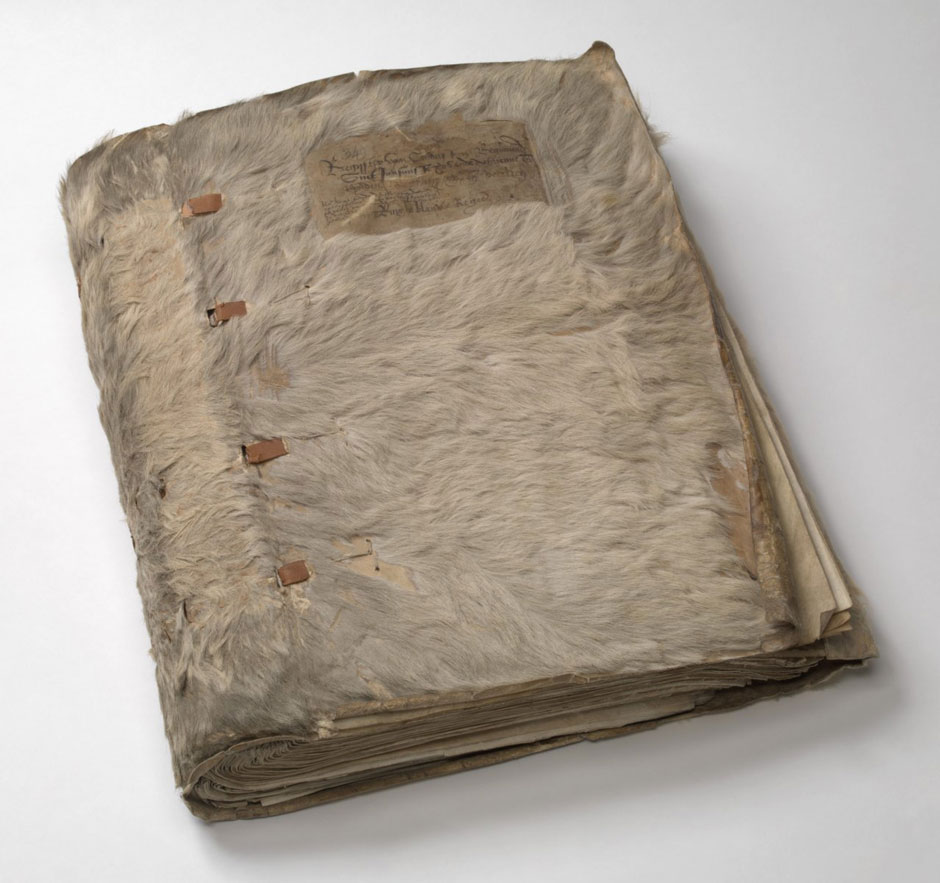

For a thousand years, the societies of the Western world transmitted and preserved much of their written cultures on and between the skins of beasts. Cows and calves, rams, ewes, and lambs, camels, deer, and fauns, goats, gazelles, and horses, seals and walruses, perhaps cats and dogs on occasion were rendered into scrolls and codices, bindings and booklets, charters and mezuzot. A large part of our written inheritance survives as a great mass of animal remains.

Parchment, a medium that came into widespread use beginning in late antiquity, has for many centuries held a special place in the cultural imagination. “When you want to have the love of whatever woman you wish,” advises a medieval necromancer’s manual, “first you must have a totally white dove and parchment made from a female dog that is in heat.” In the Talmud parchment comes in for extended discussion, much of it devoted to the ritual treatment of animal skins. Tractate Shabbath, the Talmudic book that deals with rules for the Sabbath, contains rigorous rabbinical debates over the suitability of certain kinds of membranes for sacred use: the perforated skins of birds, the split hides of cows and sheep. “Can teffilin be written on the skin of a clean fish?” a rabbi asks at one point. No, answers another–but only because of the smell.

Late medieval writers such as the anonymous author of the Middle English “Charter of Christ” likened the tortured body of Christ on the cross to a width of parchment stretched on a wooden frame, inscribed with the blood of the Passion. Shakespeare surely had such analogies in mind when writing Jack Cade’s Blackheath sermon in Henry VI, Part 2, in which the rebel leader addresses men assembled to revolt against the king. In Shakespeare’s dramatization, the leader purposefully conflates animal medium and legal message: “Is not this a lamentable thing, that of the skin of an innocent lamb should be made parchment? That parchment, being scribbled o’er, should undo a man?”

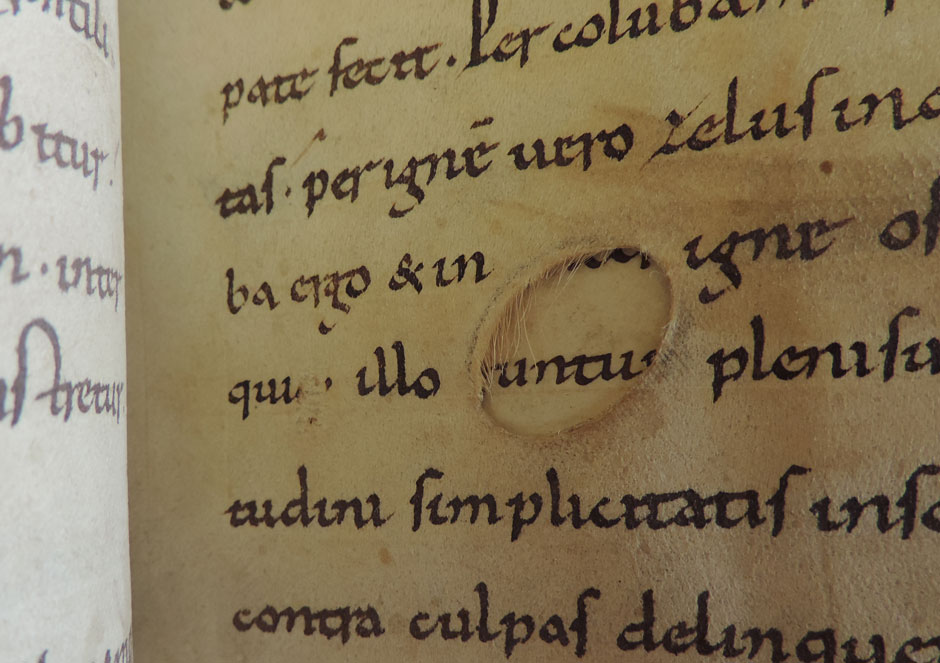

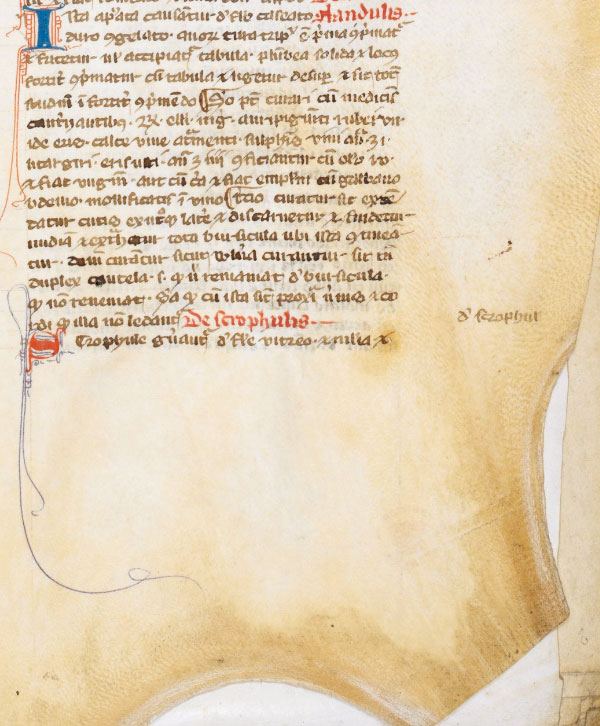

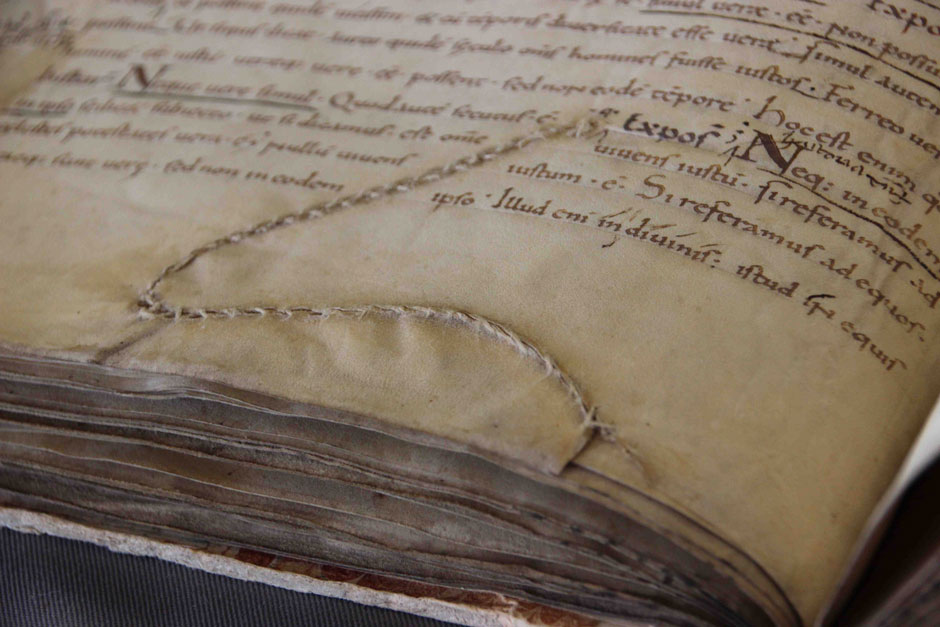

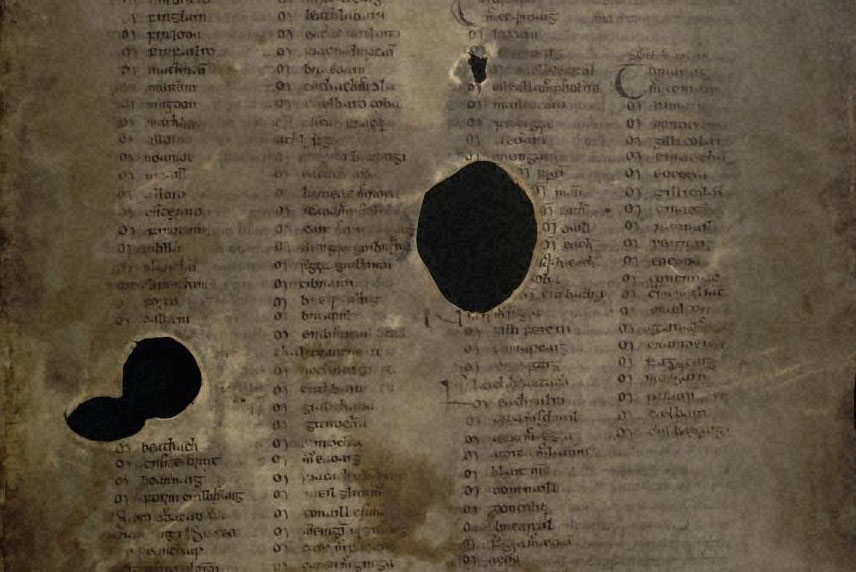

Not everyone held parchment in high esteem. Irish and Icelandic scribes complain about the poor quality of the skins (I might as well be writing on wool!), and often must content themselves with rough, uneven scraps in times of scarcity. We get a wonderful rant against the creaturely properties of parchment in the writings of Abū ʿUthmān ʿAmr ibn Baḥr al-Jāḥiẓ, a theologian, traveler, and jack-of-all-trades who died in Basra in the late 860s. Like many writers in the early Islamic world, al-Jāḥiẓ favored paper over its membrane counterpart. “Tell me why you extol writing on skins and urge me to use parchment when you know that skins are thick in bulk and heavy in weight,” al-Jāḥiẓ demands in one of his surviving letters. Skins, he avows, “have a more fetid odor” than paper. “They are aged to remove their odor and to clear away the hair. They have more knots and bulges, more troughs and dips.”

Contemporary parchment makers are all too familiar with the smelly, greasy side of their arcane craft. Jesse Meyer, a leading parchment artisan in North America, works in the family tannery in Montgomery, New York, pungent with calf hides purchased from slaughterhouses in the area and stacks of curing deerskins brought in by local hunters. In the United Kingdom, parchment is made on a more industrial scale at William Cowley, the favored purveyor to Her Majesty’s government. Remarkably, English law still requires that official copies of Acts of Parliament be printed and preserved on animal skin, inspiring occasional debates in Westminster over the ethics and economy of the parchment trade. A recommendation by the Administration Committee this session may bring the venerable tradition to an end, much to the consternation of the conservation and book arts communities.

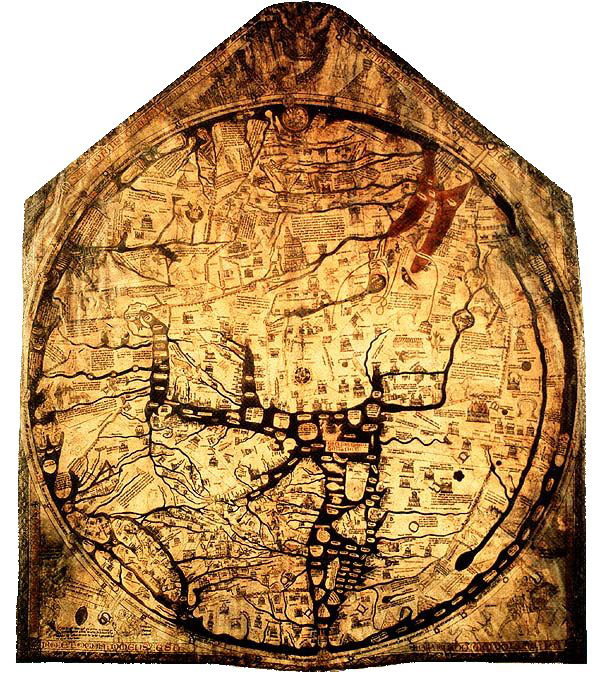

Those wanting a glimpse at the vast parchment inheritance of the premodern world can browse a nearly limitless array of membrane books and documents in digital form, now freely available through such specialized databases as Irish Scripts on Screen and The Digital Walters as well as online portals hosted by the British Library, the Bodleian Library, and even the Vatican, which is in the process of digitizing some eighty thousand of its medieval books. The latest entrant into this crowded field is the Priory Library of Durham Cathedral, which has just announced that it will be digitizing a collection of books owned and used by the Benedictines of Durham over many centuries.

Advertisement

The scholarly analysis of this sprawling resource has spawned an entire field called digital palaeography, currently in a state of glorious chaos. Its leaders—Peter Stokes, Benjamin Albritton, Ainoa Castro, Ségolène Tart, Stephen Nichols, and Martin Foys, among others—are developing rigorous new tools and methods for visualizing, annotating, and understanding this online archive in all its vastness and complexity. Foys has been working with the British Library and the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies at the University of Pennsylvania to develop an online resource for the study, annotation and linking of digital manuscript images. As Foys tells me, “The state of a manuscript as it survives today is often only the latest of several permutations. We are slowly developing the technological capacity to represent this ‘deep time’ of a manuscript digitally—how its content or material form shifts over the centuries of its existence, providing us with not a singular manuscript object, but a lived matrix of what it has been.”

Of course, none of these scholars would suggest that digitized manuscripts, however delightful or democratizing, can or should replace the real thing. Zooming in on a high-resolution magnification of a folio from the Beowulf manuscript can give an impression of breathtaking intimacy with hide and scribe alike, and emerging technologies will undoubtedly continue to yield discoveries of great importance. Yet your computer screen will tell you very little about the heft and scent of a codex, nor can your iPhone quite replicate the distinctive crinkle of a parchment folio, let alone that peachy fuzz of fine vellum on the thumb. The sensual richness of the written record confronts us like nothing else can with the sobering animality of our archive: the ghost of a spine, the curve of a haunch; patterns of scar tissue, hair follicles, sutures snaking across flayed skin; bindings as fuzzy as a cat. The written record is a vast storehouse of creaturely remains that continue to claim our attention and wonder.