Ever since I arrived in Nepal in 1975 as a Peace Corps volunteer, I have been taking photographs of the country. In the 1980s, I traveled the country by foot with a tripod-mounted camera. The photographs I took during this period show village and farm life continuing much as it had for centuries. Nepal has since been transformed by three decades of infusion from foreign development aid; remittances from the millions of Nepalis living abroad in South Asia, the Middle East, and beyond; new motor roads built into the mountains; the 1996-2006 civil war; and finally, the devastating earthquakes of April 25 and May 12, 2015.

Nearly 9,000 Nepalis were killed in the earthquakes, and over 25,000 were injured. Hundreds of thousands are still living in temporary shelters. The United Nations estimates that while 10 percent of the Nepali population—some three million residents—are in dire need of basic resources like food, shelter, and medical care, the Nepali government has made no arrangements to receive and use the $4.1 billion in donations from foreign countries and international agencies.

Through June and July this year, I watched the seasons transition in Nepal, from the blasting sun of the pre-monsoon weeks to the hard rains that come without fail at night and, without warning, during the day. Even then, there were signs of recovery. Schools began to reopen, and groups of young men and women came to Kathmandu and other localities to work, breaking down damaged buildings for the equivalent of seven to ten dollars a day.

The following photos, the first series taken in the 1980s, and the second after the earthquakes, show what has been lost both to time and to natural disaster, and just what an incredible task it will be to rebuild and restore Nepal.

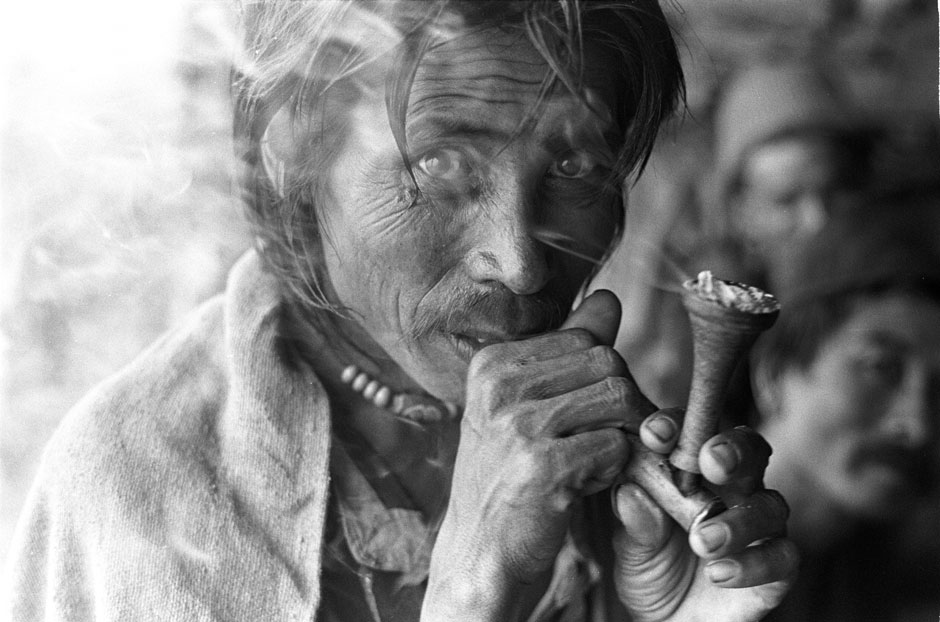

A Tamang porter (an ethnic group living in the high middle hills of Nepal) takes a tobacco break at a teashop in the village of Thare during a monsoon downpour. Before the advent of the motorway in the 1980s, Thare was the midpoint in the two-day walk between Trisuli and Dhunche in the Rasuwa district, directly north of Kathmandu, and all goods had to be portered for several days on people’s backs. This area was severely damaged by landslides resulting from the earthquakes and the deluge of monsoon rain that followed. The road north into upper Nuwakot and Rasuwa districts through Thare was hit with heavy landslides and often closed. This porter would now be in his late seventies, and his grandchildren would have no memory of this region of Nepal before the arrival of the motor road.

The shaman Shing Tchor Tamang on the porch of his house, where he and his family live and where he works, healing and performing exorcisms. Here he displays his shaman bells and drum. He uses the drum’s rhythm, the bells, and dance to induce a trance state for his shamanic practice. The village of Yarsa, which had grown immensely over the decades since 1984, was completely destroyed by the first earthquake.

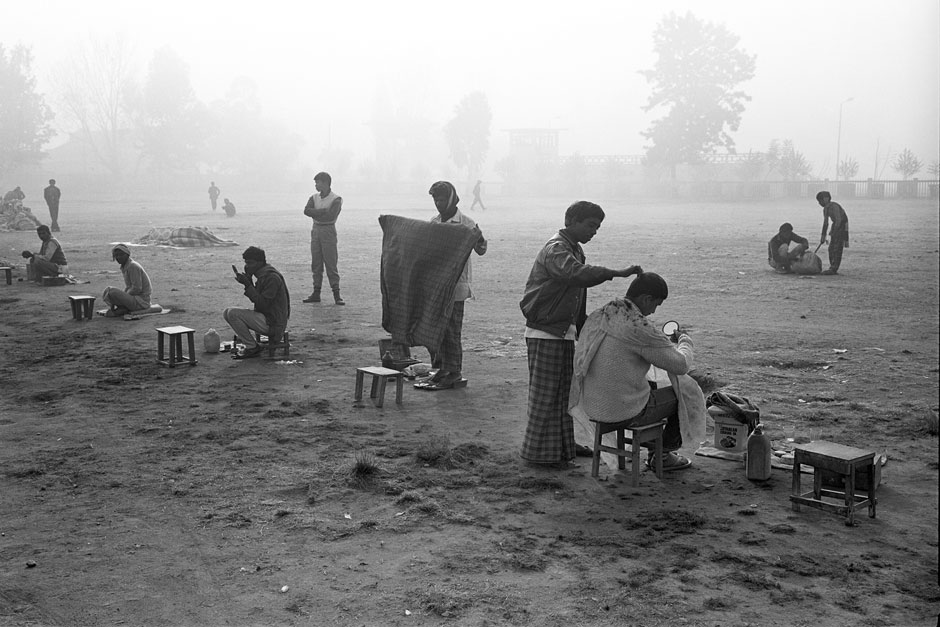

Barbers await clients in the early morning winter fog on the large open Tundikhel field in the center of Kathmandu city. Thought in mythical times to have been a playground for deities, the Tundikhel has been used for commerce, military parades, political rallies, and even rock concerts. Immediately after the earthquakes struck, the Tundikhel became a sprawling tented camp where Kathmandu residents could take refuge away from their damaged homes, unstable and still dangerous during the countless aftershocks, which continued for several weeks after the first earthquake.

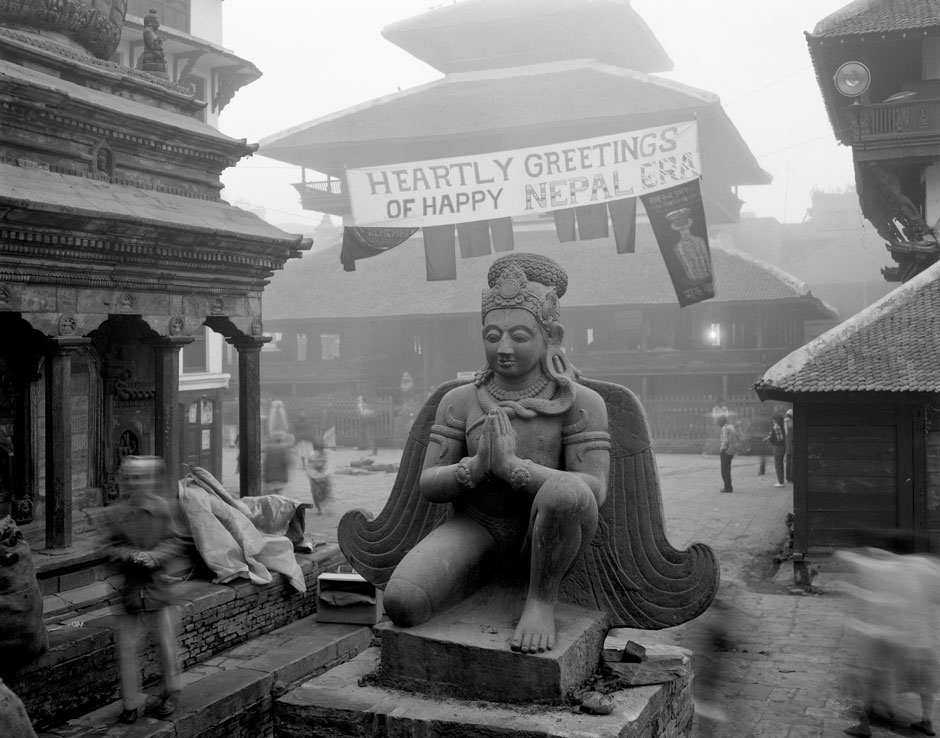

The Garuda statue from 1689, as it appeared in 1985. A representation of Vishnu’s mount with a human body and eagle wings, the Garuda kneels in proud silence in front of Kasthamandap temple in Kathmandu’s Durbar Square early on a winter morning at the time of Newar New Year. The original three-story Kasthamandap, reputed to have been built from one large tree in the twelfth century and then credited to Laxmi Narsingh Malla, who ruled from 1621-1641, was one of Nepal’s largest and most noted pagoda temples and the namesake for Kathmandu. It immediately collapsed on April 25, 2015, in the first earthquake.

Babu Kaji Sarki stands on the ruins of the house where he was born sixty-five years ago in Bungamati town, located in the southwest region of Kathmandu Valley, which includes seven World Heritage Sites—among them Kathmandu Durbar Square, the Buddhist stupas of Swayambhu and Boudha, and the Hindu temples Pshupatinath and Changu Narayan. Babu lived in this house with his wife, their son, and four grandchildren. Though the family survived, all of their belongings and food supplies were buried in the rubble, and they were forced to move to temporary shelter.

Advertisement

In Bungamati, this Newar woman (the indigenous people of the Kathmandu Valley) and her husband lost everything except the footprint of where their house stood. They have cleared away most debris and are attempting to make a safe and secure temporary shelter as they prepare for the birth of their first child.

The foundation stone and brickwork are all that remain of the Trailokya Mohan Narayan temple (completed in 1680) in Kathmandu’s Durbar Square. To the left is the terraced base of the Maju-deval temple (completed in 1690), also destroyed. These two pagoda temples were significant elements of the Kathmandu Durbar Square complex, a UNESCO World Heritage site and focal point for social and cultural daily life in downtown Kathmandu. Large piles of splintered structural and ornamental wood from the three fallen temples in Kathmandu’s Durbar Square are pushed up against the temple foundations; pedestrians and regular traffic now wind through the ruins.

Young men walk down the main street of Charikot Bazaar, the governmental headquarters for Dolakha district, east of Kathmandu. Charikot sits on a ridge with beautiful mountain views, but its positioning was precarious during the earthquakes, each of which had a different axis of motion that contributed to the severity of damage. Charikot is a popular weekend resort getaway for foreign tourists and Nepali visitors with its striking views of the 23,000-foot Himalayan peak of Gauri Sankar. While most of the tall buildings in town suffered damage from the earthquakes, the town is busy with shops and government offices have reopened.

On the road to the Buddhist Boudhanath stupa, people live in a temporary camp of tarpaulin shelters hastily built in a large vacant lot next to the Kathmandu Hyatt Regency luxury hotel. Throughout the mountainous districts of Gorkha, north and east of the capital, most village houses were destroyed or made unsafe for habitation. Of the many thousands of internally displaced villagers who sought refuge in Kathmandu, thousands lived through the monsoon in this temporary camp near the Hyatt Regency.

In the relatively new urban neighborhood of Naya Bazaar in Kathmandu, young men in flip-flops and shorts work with jackhammers and sledgehammers to break concrete from rebar webbing. Bricks are recycled, as are the pieces of rebar. For over two decades a building boom transformed Kathmandu’s skyline from traditional tile roofs and pagodas to high-rise concrete structures. The earthquakes have halted building and many of the construction workers are now earning money as “building breakers.” One common practice is to punch holes through the floors of the buildings so that debris falls through the holes to the lower levels. The work is risky since the structures, initially dangerous from the earthquake damage, are made ever more perilous during the deconstruction process.

At mid-morning laborers take a break from their heavy work tearing down buildings. These four young men came to Kathmandu looking for work after the earthquakes. They live in the building that they are tearing down with eight other friends from villages in the southeastern Udayapur district. These workers, numbering in the several thousands across Kathmandu and other affected areas, are paid by the owners of the properties that they deconstruct. Their numbers will likely increase as funding is released and Nepal moves forward into the long-term reconstruction phase.