I was born in England in 1948, late enough to avoid conscription by a few years, but in time for the Beatles: I was fourteen when they came out with “Love Me Do.” Three years later the first miniskirts appeared: I was old enough to appreciate their virtues, young enough to take advantage of them. I grew up in an age of prosperity, security, and comfort—and therefore, turning twenty in 1968, I rebelled. Like so many baby boomers, I conformed in my nonconformity.

Without question, the 1960s were a good time to be young. Everything appeared to be changing at unprecedented speed and the world seemed to be dominated by young people (a statistically verifiable observation). On the other hand, at least in England, change could be deceptive. As students we vociferously opposed the Labour government’s support for Lyndon Johnson’s war in Vietnam. I recall at least one such protest in Cambridge, following a talk there by Denis Healey, the defense minister of the time. We chased his car out of the town—a friend of mine, now married to the EU high commissioner for foreign affairs, leaped onto the hood and hammered furiously at the windows.

It was only as Healey sped away that we realized how late it was—college dinner would start in a few minutes and we did not want to miss it. Heading back into town, I found myself trotting alongside a uniformed policeman assigned to monitor the crowd. We looked at each other. “How do you think the demonstration went?” I asked him. Taking the question in stride—finding in it nothing extraordinary—he replied: “Oh I think it went quite well, Sir.”

Cambridge, clearly, was not ripe for revolution. Nor was London: at the notorious Grosvenor Square demonstration outside the American embassy (once again about Vietnam—like so many of my contemporaries I was most readily mobilized against injustice committed many thousands of miles away), squeezed between a bored police horse and some park railings, I felt a warm, wet sensation down my leg. Incontinence? A bloody wound? No such luck. A red paint bomb that I had intended to throw in the direction of the embassy had burst in my pocket.

That same evening I was to dine with my future mother-in-law, a German lady of impeccably conservative instincts. I doubt if it improved her skeptical view of me when I arrived at her door covered from waist to ankle in a sticky red substance—she was already alarmed to discover that her daughter was dating one of those scruffy lefties chanting “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh” whom she had been watching with some distaste on television that afternoon. I, of course, was only sorry that it was paint and not blood. Oh to épater la bourgeoisie.

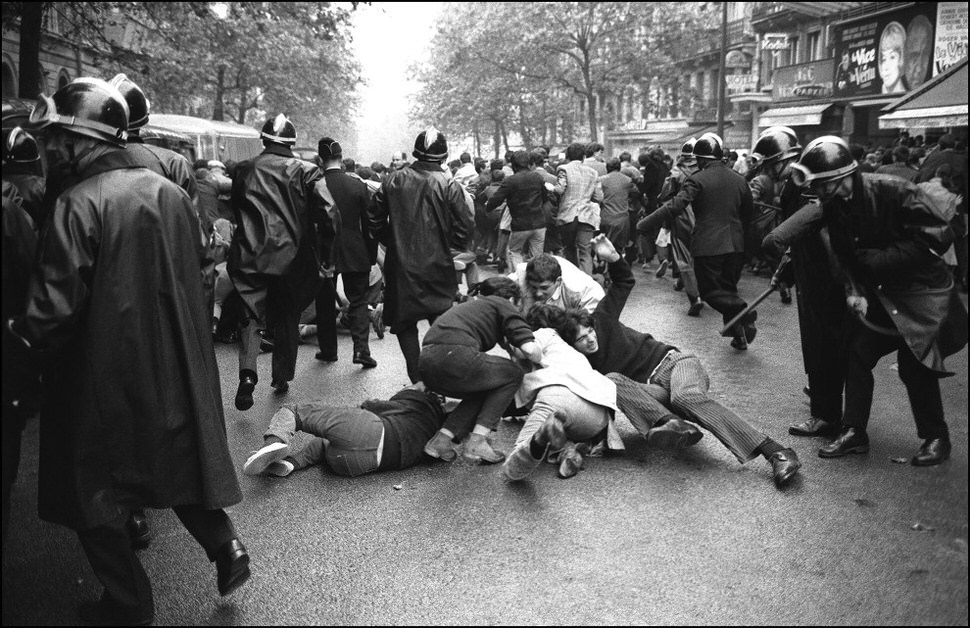

For real revolution, of course, you went to Paris. Like so many of my friends and contemporaries I traveled there in the spring of 1968 to observe—to inhale—the genuine item. Or, at any rate, a remarkably faithful performance of the genuine item. Or, perhaps, in the skeptical words of Raymond Aron, a psychodrama acted out on the stage where once the genuine item had been performed in repertoire. Because Paris really had been the site of revolution—indeed, much of our visual understanding of the term derives from what we think we know of the events there in the years 1789-1794—it was sometimes difficult to distinguish between politics, parody, pastiche…and performance.

From one perspective everything was as it should be: real paving stones, real issues (or real enough to the participants), real violence, and occasionally real victims. But at another level it all seemed not quite serious: even then I was hard pushed to believe that beneath the paving stones lay the beach (sous les pavés la plage), much less that a community of students shamelessly obsessed with their summer travel plans—in the midst of intense demonstrations and debates, I recall much talk of Cuban vacations—seriously intended to overthrow President Charles de Gaulle and his Fifth Republic. All the same, it was their own children out on the streets, so many French commentators purported to believe this might happen and were duly nervous.

By any serious measure, nothing at all happened and we all went home. At the time, I thought Aron unfairly dismissive—his dyspepsia prompted by the sycophantic enthusiasms of some of his fellow professors, swept off their feet by the vapid utopian cliches of their attractive young charges and desperate to join them. Today I would be disposed to share his contempt, but back then it seemed a bit excessive. The thing that seemed most to annoy Aron was that everyone was having fun —for all his brilliance he could not see that even though having fun is not the same as making a revolution, many revolutions really did begin playfully and with laughter.

Advertisement

A year or two later I visited a friend studying at a German university—Goettingen, I believe. “Revolution” in Germany, it turned out, meant something very different. No one was having fun. To an English eye, everyone appeared unutterably serious—and alarmingly preoccupied with sex. This was something new: English students thought a lot about sex but did surprisingly little; French students were far more sexually active (as it seemed to me) but kept sex and politics quite separate. Except for the occasional exhortation to “make love, not war,” their politics were intensely—even absurdly—theoretical and dry. Women participated—if at all—as coffee makers and sleeping partners (and as shoulder-borne visual accessories for the benefit of press photographers). Little wonder that radical feminism followed in short order.

But in Germany, politics was about sex—and sex very largely about politics. I was amazed to discover, while visiting a German student collective (all the German students I knew seemed to live in communes, sharing large old apartments and each other’s partners), that my contemporaries in the Bundesrepublik really believed their own rhetoric. A rigorously complex-free approach to casual intercourse was, they explained, the best way to rid oneself of any illusions about American imperialism—and represented a therapeutic purging of their parents’ Nazi heritage, characterized as repressed sexuality masquerading as nationalist machismo.

The notion that a twenty-year-old in Western Europe might exorcise his parents’ guilt by stripping himself (and his partner) of clothes and inhibitions—metaphorically casting off the symbols of repressive tolerance—struck my empirical English leftism as somewhat suspicious. How fortunate that anti-Nazism required—indeed, was defined by—serial orgasm. But on reflection, who was I to complain? A Cambridge student whose political universe was bounded by deferential policemen and the clean conscience of a victorious, unoccupied country was perhaps ill-placed to assess other peoples’ purgative strategies.

(Magnum Photos)

I might have felt a little less superior had I known more about what was going on some 250 miles to the east. What does it say of the hermetically sealed world of cold war Western Europe that I—a well-educated student of history, of East European Jewish provenance, at ease in a number of foreign languages, and widely traveled in my half of the continent—was utterly ignorant of the cataclysmic events unraveling in contemporary Poland and Czechoslovakia? Attracted to revolution? Then why not go to Prague, unquestionably the most exciting place in Europe at that time? Or Warsaw, where my youthful contemporaries were risking expulsion, exile, and prison for their ideas and ideals?

What does it tell us of the delusions of May 1968 that I cannot recall a single allusion to the Prague Spring, much less the Polish student uprising, in all of our earnest radical debates? Had we been less parochial (at forty years’ distance, the level of intensity with which we could discuss the injustice of college gate hours is a little difficult to convey), we might have left a more enduring mark. As it was, we could expatiate deep into the night on China’s Cultural Revolution, the Mexican upheavals, or even the sit-ins at Columbia University. But except for the occasional contemptuous German who was content to see in Czechoslovakia’s Dubcek just another reformist turncoat, no one talked of Eastern Europe.

Looking back, I can’t help feeling we missed the boat. Marxists? Then why weren’t we in Warsaw debating the last shards of Communist revisionism with the great Leszek Kolakowski and his students? Rebels? In what cause? At what price? Even those few brave souls of my acquaintance who were unfortunate enough to spend a night in jail were usually home in time for lunch. What did we know of the courage it took to withstand weeks of interrogation in Warsaw prisons, followed by jail sentences of one, two, or three years for students who had dared to demand the things we took for granted?

For all our grandstanding theories of history, then, we failed to notice one of its seminal turning points. It was in Prague and Warsaw, in those summer months of 1968, that Marxism ran itself into the ground. It was the student rebels of Central Europe who went on to undermine, discredit, and overthrow not just a couple of dilapidated Communist regimes but the very Communist idea itself. Had we cared a little more about the fate of ideas we tossed around so glibly, we might have paid greater attention to the actions and opinions of those who had been brought up in their shadow.

No one should feel guilty for being born in the right place at the right time. We in the West were a lucky generation. We did not change the world; rather, the world changed obligingly for us. Everything seemed possible: unlike young people today we never doubted that there would be an interesting job for us, and thus felt no need to fritter away our time on anything as degrading as “business school.” Most of us went on to useful employment in education or public service. We devoted energy to discussing what was wrong with the world and how to change it. We protested the things we didn’t like, and we were right to do so. In our own eyes at least, we were a revolutionary generation. Pity we missed the revolution.

Advertisement

—“Revolutionaries” is part of a continuing series of memoirs by Tony Judt, and appears along with two others in the February 25 issue of the Review.