I left the New Museum’s “The Last Newspaper”—a show that sets out to explore the relation between newspapers and art at the end of the print era—with my fingers black from printer’s ink, just as they used to be years ago when I read the Times every morning on the subway. I can’t remember when they were last begrimed that way, and don’t know whether that is more reflective of the fact that newspapers today use higher-quality inks, or that I tend to read the news online more often than on paper, or that I no longer ride the subway to work. Some of the museum’s ink came from the two newspapers that are published at the exhibition itself and constitute works in the show: the broadsheet New City Reader (edited by Joseph Grima and Kazys Varnelis) and a tabloid, edited by the Barcelona-based curatorial office Latitudes, that has been variously called The Last Post, The Last Gazette, and The Last Register.

The broadsheet is concerned with “architecture, public space, and the city” and its poster-size dimensions (15½” x 23″ folded) and epic layouts are intended for wall display. The tabloid, which focuses on newspapers, as well as on the show itself, is rather more puckish. The Last Gazette includes, for example, a record of a quixotic attempt by Ines Schaber to approach the underground facility in western Pennsylvania where the photo agency Corbis keeps its archive of some 70 million pictures. The story evokes the cold-war espionage genre—an unremarkable setting masks a culture of such militant secrecy that the best the author could manage is a murkily distant photo of the facility’s parking lot. Its meandering text and bland snapshots, on the other hand, evoke the whimsical record-keeping of 1970s conceptual art, which is rather more in keeping with the spirit of the show. There were, indeed, many aspects of the New Museum exhibit that reminded me of Information, the 1970 show at the Museum of Modern Art, conceived by Hans Haacke and curated by Kynaston MacShine, with its polls, suggestion boxes, and works in which text dominated the visual content, all of which had alternately beguiled and frustrated me as a 16-year-old.

The exhibit’s third-floor entry appears to be a hive of activity. A jumble of tables hold the two in-house newspapers’ minimal editorial offices, interactive installations by the Center for Urban Pedagogy and by StoryCorps, the compilers of oral history for public radio, and a station where visitors are encouraged to tear up newspapers and creatively pin the resulting scraps on a board—”Create your own news stories!” On the day I visited, the board held a handful of ragged items, the tables hosted a number of people clicking on laptops, and Urban Pedagogy’s set-up entertained a few children with its brightly colored plastic bricks, meant to illustrate either zoning or the affordability of housing.

But many of the show’s participatory ambitions appeared unfulfilled. No one was discussing the issues of the day on the large blue circular rug provided for the purpose on the fourth floor, and, three weeks into the show’s term, no one had yet taken advantage of the free advertising offered by the two papers. Clearly, such stabs at eliciting dialogue, as well as the piles of newsprint given out for free (which also include Old News, a project the Swedish artist Jacob Fabricius has been spearheading since 2004, in which artists from various countries are asked to compile stories and photographs from their local newspapers, the results of which are then reprinted), nod to the theme of potlatch that has been prominent in the art world since the late Cuban artist Félix Gonzàlez-Torres invited gallery visitors, in 1991, to take candies from an enormous pile. Many of the interactive features of this show, however, suggest a setting other than a museum exhibit—a three-day conference, perhaps, or a permanent installation in some public space, in any case someplace that bears repeated visits, rather than a show costing $12 per ticket.

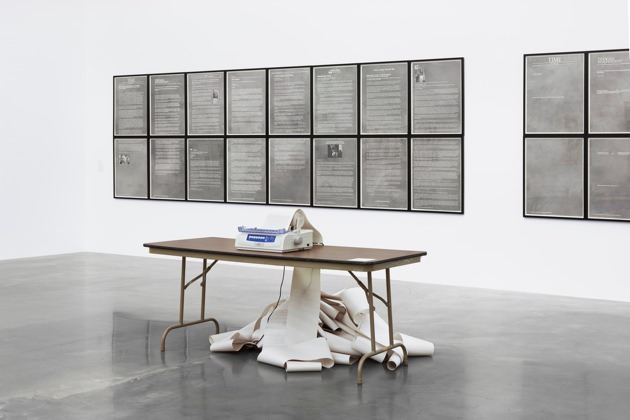

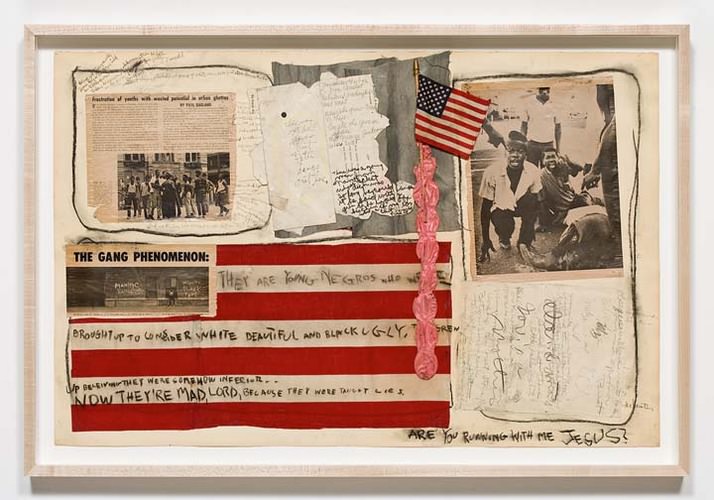

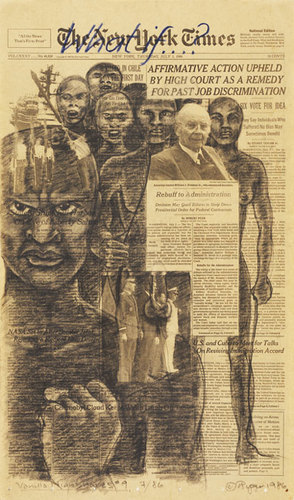

The conceptual pedigree of the exhibit is illustrated by its key historical work, News (1968) by the artist and investigative provocateur Hans Haacke, which consists of a teletype machine spitting out the latest stories from the wire services, its ribbonlike paper piling into a small mountain on the floor. No one consulted the feed while I was there—and why should they, since they could obtain the same information with less trouble from their phones? In 1968 the piece may have had a raw immediacy that bridged the gap between a sacrosanct museum space and a turbulent outside world, but in the present day its obsolete technology reduces it to the status of historical curiosity. Few other works date back to the time when newspapers were vital. A pair of collages by Judith Bernstein from 1967-68, including race-war photos and scrawled rants, evoke the angry layouts of the underground press. Sarah Charlesworth’s 1979 series, concerning the death of an American TV cameraman at the hands of Somoza’s forces in Nicaragua, isolates blurry photocopied news items on acres of gray background and looks at once agitated and modish in a very 1979 way. Adrian Piper’s Vanilla Nightmares, which dates from 1986, is a series of drawings of angry African-American figures done directly on Times front pages that feature race-relations stories.

Advertisement

But this is not a historical survey of newspaper art. There are no Cubist collages or Warhol tabloid pages or Rauschenberg wire-photo assemblages. The show is primarily about the present day, which means that the pieces are more concerned with appearance than with substance. One of the few exceptions to this rule is Wolfgang Tillmans’s Truth Study Center, which occupies yet another set of tables on the third floor. It is an ongoing, intermittently updated work in which Tillmans juxtaposes cut-out news items with his own photographs and lays them out under glass, addressing a variety of political issues—human rights, religious violence—in a way that is genuinely provocative. Yet the display that stayed with me was a single item that covered a whole table, Naomi Wolf’s “Fascist America, in 10 Easy Steps,” published in The Guardian in 2007.

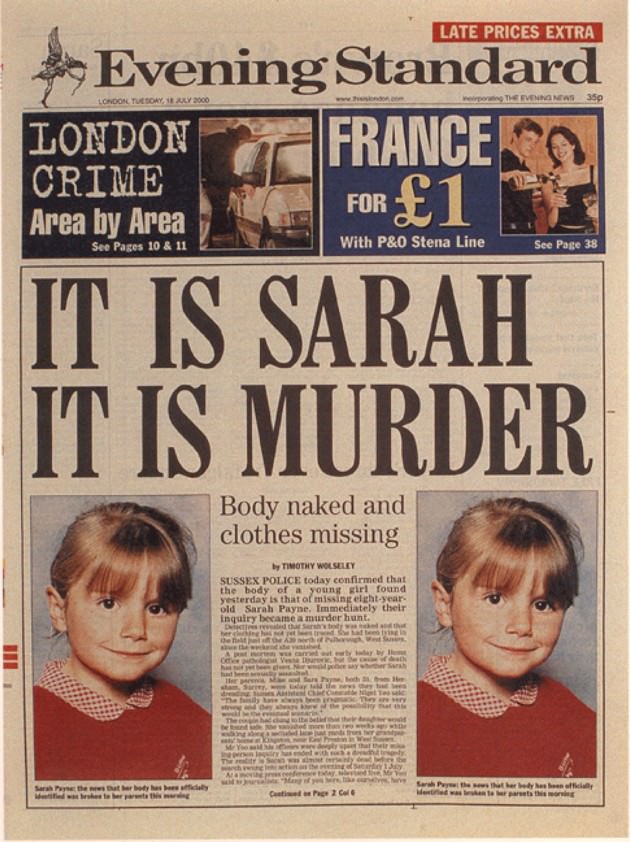

Elsewhere, Thomas Hirschhorn covers evening gowns with a variety of newspaper headlines and photographs—some current and others unplaceable. Pierre Bismuth reprints various front pages with the lead photo doubled, apparently to suggest its intensity. Nate Lowman, who describes himself as an “image thief”—as who isn’t nowadays?—makes attractive silkscreens from sundry clipped-out bits and bobs. The late Dash Snow framed a series of hyperventilating New York Post front pages on the subject of Saddam Hussein, having first crumpled them and covered them with glitter. Aleksandra Mir makes oversized copies of Post front pages in a cartoonish freehand style—which actually manage to look barely more cartoonish than the actual Post front pages.

Perhaps a more focused show might simply have let a selection of artists run amok with the Post, and in fact you could probably populate a fairly substantial exhibit with works on that subject going back to when Rupert Murdoch first bought the paper. If the show also included all the band flyers, record jackets, and T-shirt designs that have been filched from the Post over the years, it might fill the entire museum.

“The Last Newspaper” wants to be urgent, immediate, and democratic at the same time as it is chic, cutting-edge, and art world-savvy. While it may have enough of the right names to satisfy the second part of this ambition, its attempt at the first is no more successful than the regular efforts made by whoever curates the Whitney Biennial. For all that numerous artists and curators genuinely believe themselves to be engaged, the art world is too rich, too hermetic, and too pleased with itself to have any more rapport with what is happening “on the street” than did the art establishment Hans Haacke and cohorts were trying to overturn circa 1968. But then, in taking on the lame-duck medium that is the newspaper, the show is even further insulated from actuality.

Newsprint still manages to connote urgency, at least in the way that Che Guevara’s stenciled face persists in connoting revolution, but the connotation here stands bereft of real context. While the show conveys an appreciation for the newspaper as object, as texture, as semiotic marker, most of the works on display are so far from engaging with the idea of the newspaper as vital carrier of immediate information that the exhibit might as well date from a time long after the final passing of the medium. The show’s primary message seems to be that since the flavor of the newspaper—so piquant, so gritty, so salt-of-the-earth—is on the verge of disappearance, it may be the last time that an aesthete can experience the bouquet of printer’s ink: ash, black pepper, cordite, with a hint of brimstone.

The Last Newspaper is on view at the New Museum in New York through January 9, 2011.