Cave of Forgotten Dreams, a new documentary by Werner Herzog, is a striking and characterful work of art, framing another that is wholly extraordinary. In 1994 three experienced French speleologists, exploring the limestone gorges of the river Ardèche, crawled their way into a large cave system in which Palaeolithic imagery swung into view. Jean-Marie Chauvet, the team’s leader, has described how they were immediately awestruck by the “remarkable realism” and “aesthetic mastery” of the countless animal depictions that sprang out as their torch-beams roved the cave walls. But conscious that cave paintings such as those at Lascaux, discovered in 1940, had soon become infested with the mold carried on visitors’ breaths, Chauvet and his colleagues notified the regional authorities, and within a month, before publicly announcing the discovery, a steel door was installed to seal off the opening in the rock-face. Only the scientifically qualified might pass inside, and those in very small numbers, confining their footsteps to a narrow raised walkway.

Illustrated surveys were published, edited first by Chauvet (after whom the cave got named), and then by Jean Clottes, the presiding archaeologist. Meanwhile lay inquirers such as Judith Thurman, writing about Chauvet for The New Yorker in 2008, had no choice but to report on the paintings at second hand. But Thurman’s piece fired up Erik Nelson, a Los Angeles producer who, having already worked on two documentaries with Herzog, saw fresh cinematic potential here for the veteran Bavarian-born auteur; and Nelson’s company had the smart idea of presenting Herzog to Frédéric Mitterrand, France’s new minister of culture. In Mitterrand (nephew to the late president) they encountered a dedicated cinephile who unhesitatingly made it his business to beat a path open for the filmmakers. For four days, then, during the spring of last year, Herzog and a minimal, three-man crew were granted access to that subterranean walkway.

The project had a powerful hook line. Radiocarbon analyses indicate that charcoal used by painters at Chauvet comes from pines that were alive some 32,000 years ago. It follows that these are easily the world’s oldest known paintings. Long before the eighteenth millennium BCE—the date assigned to Lascaux—a rock-fall had closed off Chauvet’s original entrance, stopping all further incursion into the cave and preserving the imagery within in pristine condition. The only figurative artifacts that we know to predate Chauvet are some slightly older carvings in stone and mammoth ivory dug up from cave floors in Swabia (in southern Germany) and Austria. Herzog brings these sculptures into his film, along with some flutes carved from bone found at the same sites. Looking at these remains, so it strikes him, we are looking at the very roots of art and of music. “It is as if,” he at one point muses, “the human soul had awakened here.” And he presses the archaeologists, as he interviews them outside the cave: “What constitutes humanness?”

This documentary, in other words, cleaves to the customary interests of Herzog’s cinema. As in his previous projects with Nelson he looks for a limit case on what it means to walk the face of the earth: In Grizzly Man, a nature-lover’s notion that he could commune with Alaska’s bears got fatally rebuked, and in Encounters at the End of the World, intruding researchers emerged equally as anomalies, silhouetted against the wilderness of Antarctica. Cave of Forgotten Dreams opens on cultivation: neat vine rows below cliffs bristling with Mediterranean scrub. But from them the camera zooms out and overhead to survey the Ardèche gorge and its staggering natural singularity, the Pont d’Arc, an arch cut through the limestone by the river half a million years ago. The sublime takes priority in Herzog’s world. It was that great spectacle, his commentary suggests, that catalyzed palaeolithic nomads into their burst of artistic expressiveness nearby.

Very soon humans are seen traversing the landscape, step by sweated step: a team of rucksacked archaeologists heading for the steel door. Walkers like these have passed through Herzog’s films ever since 1972’s Aguirre, but here no world-defying zany, Klaus Kinski-style, drives them on. Archaeology nowadays, a practitioner explains to Herzog, deals not in heroics but in high-tech, and his colleagues pass their days coolly among stratigraphic analyses and laser scans. At the same time, a member of the site team, the pony-tailed Julien Monney, turns away from his desktop screen to assert that “I am a scientist, but I am a human being also.” What were you doing before? Herzog asks him. “I was in the circus.” Lion-taming? “Unicycling.”

Prodding and delving like this, Herzog constantly touches on the quaintly ludicrous. The amateur enthusiasts are irresistible. He meets the bearded and reindeer skin-clad Wulf Hein, an investigator into Ice Age technologies, who coyly blows into a pentatonic Palaeolithic flute and comes up with the Star Spangled Banner. Meanwhile the elderly Maurice Maurin roves the Ardèche poking his nose into rockfaces, hoping to sniff vapors emitted by as yet undiscovered caves. Monsieur Maurin presents his olfactory credentials, explaining that he was formerly the president of the Société Française des Parfumeurs. The director, himself in his late sixties, passes a forbearing avuncular comment on Maurin’s “sense of wonder.” He relishes his role as a sage, a mellowed authoritarian: his way with English vowels, as he speculates over prehistoric “seeriemoanies,” (i.e., ceremonies) adds to the sweet-hearted comedy.

Advertisement

But Herzog has a new joke to deliver. Jean-Michel Geneste, Clottes’s successor as head of the research project, clowns to the camera, brandishing a Stone Age spear. It seems to lunge straight into you, for you have been supplied with Hollywood’s favorite gimmick of the past few seasons, 3-D specs. And then the projecting spear-end slips out of frame—presenting you with a bizarre perceptual paradox, Avatar colliding with M.C. Escher. Mocking art-house snootiness by employing the novel medium, Herzog also teases the notion that by this route, film gets to feel “more real.” His own aesthetic (National Geographic meets Theatre of the Absurd, you might say) has always spurned everyday notions of the factual and real in favor of loftier forms of truth—poetic, ecstatic. But it is not just those values that prompted him to jump technologies here, for it turns out that the poetry he is concerned with is crucially reliant on the nature of curving surfaces.

The sequencing takes us in through that cliff-face door, away from sunlit faces and landscapes and down the torchlit shaft leading to the cave’s long chambers. These stretch back some eight hundred feet. The cave’s miracles of geology—the extravagance of its glittering stalagmites and calcite curtains—surpass those of the Pont d’Arc outside. But the chambers also have undulating walls, and it was on these that the ancient artists chiefly worked. We are given a foretaste of their images: we exit; we return to this item, to that; we leave again. “It is a relief to go outside,” Herzog explains: inside the caves we get to feeling “as if we were disturbing,” as if our distant ancestors’ eyes were still upon us. But finally we surrender to the flow of their art, immersed at length in the interplay of torchlight, rippling cave flanks, scorings, charcoalings and red ochre.

It was here, paradoxically, that I felt least at ease with Herzog’s distinctive approach to documentary. As with many a serious artist, he yearns to let something excessive come through. Visual art might be a conduit for that sublime and so might music—which, many times formerly, has transformed the imaginative space of his movies. “There is never anything like ‘background music’ in my films,” he has said. Accordingly he wills miracles to well up from the players he has chosen. Fittingly enough, here we hear a flautist, alongside the haunting, earthy juddering of a violoncello played by the composer Ernst Reijseger. But those are not sufficient. Those putative Palaeolithic “seeriemoanies” must somehow be invoked: cue choirs, cooing high and low in attendance on the art. Their cod-liturgical scat had me muttering that one man’s poetic truth is another man’s gloopy bogosity.

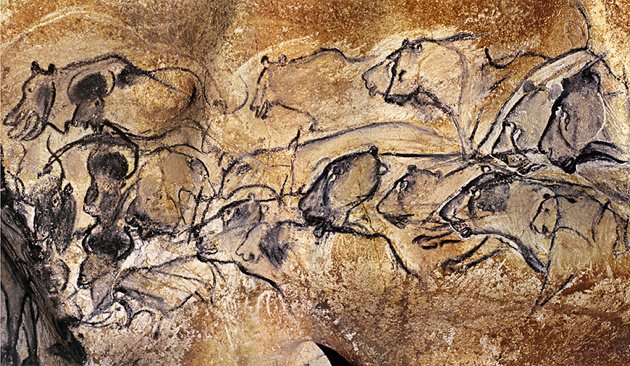

If only Herzog had trusted to the silence that he tells us rules over the caverns! Yet there is no constraining the ravishing visual spectacle. The passages of imagery on which the 3-D camera chiefly feasts lie towards the back of the cave system. They would have been prefaced, had you entered during the Stone Age, by red handprints, then by drawings of bears and of panthers, as the final glimmers of daylight vanished and you took your torch into the deep interior. There, at a fork where two rear chambers head off, a great surge of beasts—reindeer, horses, bison, aurochs, rhinos, spread across some fifty feet—has been summoned from the rock’s convolutions. They spring and tumble across its folds, hurtling, hovering or hiding: across one concavity, two rhinos turn to fight it out, horn to horn. At some points rapid outlines seize beasts by their essences: at others they are colored, fleshly beings, rendered by fine modeling.

Is it right to treat this exultant phantasmagoria by unknown hands as a work of art, when there is so little external evidence to supply it with a socio-cultural context? It’s impossible not to, the more you keep looking. Everywhere a sure grasp of appearances and inspired graphic judgments serve a cohesive dramatic scheme: unlike many another cave wall elsewhere, this is no mere doodle-board. Besides, the researchers that Herzog interviews assure him that one of its climactic images—a group of four exquisitely modeled and individualized horse heads—is certainly the work of a single hand.

Advertisement

Still further in, down one of rear caverns, lies an array of lion heads, equally excessively alive: and beyond them, a dangling pinnacle that tantalizes Herzog. It shows the forequarters of a bison surmounting a woman’s sex. That is the lone glimpse of the human figure that Chauvet offers him, and in a hunt for correlatives he heads off to those Swabian caves, which recently yielded up the world’s oldest known sculpture: the “Hohle Fels Venus,” two-and-a-half inches of ivory carved 35,000 years ago. Her looming breasts, rotated in 3-D, tally with Herzog’s droll voiceover about “visual conventions which extend all the way beyond Baywatch.” Equally, the female-plus-bovine combination reminds him of Picasso. And are not the rolling, torchlit rock-waves of animals—one bison set in motion on eight legs—“almost a form of proto-cinema”? Such ever-present urges, such timelessly immediate techniques, place us in a long continuum: here is “the modern human soul,” as Herzog has repeatedly remarked when interviewed about the film, and on a certain deep level we are at one with these archaic dreamers, whose imaginations may have gained them an evolutionary advantage as they wrested the land from the artless Neanderthals.

Or is it that we understand nothing? A majestically bizarre coda, switching from that subterranean bestiary to a pair of albino crocodiles currently swimming the waters near an adjacent nuclear plant, lets go of the whole tension between Palaeolithic handiwork and twenty-first-century guesswork, poetically proposing that like the twinned freak reptiles, ancient and modern mirror one another, each a form of unreality. That long continuum of human culture ends up bracketed, in Herzog’s vision, within the mythic “dreamtime” of the Australian Aborigines—who, as the ponytailed Monney points out, are our most recent informants on Stone Age philosophy. After all, he and his fellow scientists are presented here, for all their inquisitive rigor, as little but airy and childlike romantics.

That soft agnostic dissolve frustrates me. It’s not that I see much reason to buy a skeptical argument making the archaeological rounds, whispering that the radiocarbon datings are somehow unreliable and that actually Chauvet is little older than Lascaux. All that seems to be behind this is a presumption that Chauvet’s artworks, with their stunning naturalism and graphic assurance, are far too sophisticated to stand at the head of a tradition. But then we have too little to go on—as yet—to know what the substance of that tradition was, or how it developed. All but the merest sliver of Palaeolithic creativity must long since have perished above ground. The heady visual surfeit offered by Herzog’s film leaves me with a nagging hunger for some further nugget that might illuminate the mystery of the art’s meanings. Find me more clues, find me more caves. Keep sniffing, Monsieur Maurin.

Cave of Forgotten Dreams, directed by Werner Herzog, is playing at theaters in London, Chicago, and Los Angeles, and is being shown at the IFC Center in New York through May 12.