It’s been a particularly busy season for admirers of the world’s first and greatest consulting detective, Mr. Sherlock Holmes of 221B Baker Street. In November, with the explicit approval of the estate of Arthur Conan Doyle, Anthony Horowitz published his The House of Silk, held back for years by Dr. Watson as one of those cases “for which the world is not yet prepared.” Ever since The Beekeeper’s Apprentice (1994), Laurie R. King has been chronicling the later adventures of Holmes and his young American partner—and wife!—Mary Russell, and in last year’s Pirate King the duo found themselves caught up in a mystery set during the production of a silent-film epic. King also teamed up with Leslie R. Klinger—editor of The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes—to bring out A Study in Sherlock, a collection of new stories about Holmes from distinguished writers, including one by Neil Gaiman (“The Case of Death and Honey”) that has just been nominated for an Edgar Award by the Mystery Writers of America.

In a more academic vein, Doylean scholars Jon Lellenberg and Daniel Stashower, along with Rachel Foss of the British Library, have just overseen the publication of Conan Doyle’s long-lost first novel, The Narrative of John Smith. Laid up with gout, its protagonist reflects on life, literature, and the people around him. Highly autobiographical, the result is fascinating, but it won’t dislodge The Hound of the Baskervilles as anyone’s favorite Conan Doyle novel.

All these books, meanwhile, were overshadowed by the two recent reimaginings of Holmes and Watson for the screen. The BBC Sherlock series starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman brilliantly translates the stories into the present. (The second set of three episodes has just concluded in Britain and will be aired on PBS this spring. Notoriously, Irene Adler—“To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman”—is portrayed as a leather-clad dominatrix.) In Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, the sequel to the 2009 film Sherlock Holmes, Robert Downey Jr. and Jude Law continue their transformation of the Victorian duo into gritty, steampunk action heroes. The movie’s many explosions, elaborately choreographed fight scenes, and double-entendres recall modern superhero comics far more than cerebral mysteries of the hansom-cab era.

Naturally enough, talk about the two filmed versions of Sherlock Holmes dominated the cocktail chatter at January’s meeting of the mysterious Sherlockian literary and dining club, The Baker Street Irregulars. Most Irregulars felt that the screen versions would renew interest in the original adventures and bring younger people to the “Sacred Writings,” that is, the fifty-six short and four long cases also known as “the canon.” Nonetheless, some felt disgruntled by the many liberties taken, and shuddered to think that today’s twelve-year-old would visualize Holmes as either an Aspergerian sociopath or a nineteenth-century version of Indiana Jones. Of course Irregulars have been arguing about every aspect of Sherlock Holmes for more than seventy-five years—from the finest Holmes story (“The Redheaded League”? “Silver Blaze”? “The Final Problem”?) to the best screen interpretation of the detective (Basil Rathbone and Jeremy Brett both have their ardent supporters). But there’s no denying that the BSI welcomes the resurgence of Holmes and Watson: the new interest reminds everyone—and especially a younger generation—that Sherlock Holmes still lives for all those who “keep green the memory of the Master.”

Founded in 1934 by the novelist and critic Christopher Morley, who had virtually memorized the canon during his Baltimore childhood, The Baker Street Irregulars takes its name from the street urchins who sometimes assist the detective because, as he says, they can “go everywhere, see everything, and overhear everyone.” About three hundred invested members—lawyers, doctors, writers, librarians, booksellers, teachers, and businesspeople from all over North America and Britain, not to mention Europe, Japan, Australia—belong to the group, which each year meets in Manhattan in early January. Why January? Because intensive analysis of the stories reveals that Holmes was almost certainly born on January 6, 1854.

Sherlockian “scion societies” exist in most big cities—e.g. The Speckled Band of Boston, The Red Circle of Washington, DC—and welcome anyone with an interest in the sleuth of Baker Street. But investiture in the national organization is reserved for the most active or distinguished followers of the Master. Over the decades members of the BSI have included the mystery novelists Rex Stout and Frederic Dannay (one half of Ellery Queen), two presidents (Roosevelt and Truman), and, more recently, the former chief technical officer of Apple, a retired judge of the New York State Court of Appeals, and the longtime head chef of the Culinary Institute of America. Invested members sport distinctive ties or rosettes containing blue, purple, and mouse (a kind of grey), colors associated with Sherlock Holmes’s various dressing gowns.

Advertisement

They also each receive a name drawn from the canon, usually chosen to allude to a person’s personality or profession. Mine is “Langdale Pike,” a newspaper gossip columnist who appears in “The Three Gables.” At one point in that adventure, Holmes exclaims, “Watson, this is a case for Langdale Pike, and I am going to see him now.” Shortly after my investiture in 2002, I naturally produced a spoof metafiction in which I traced Pike’s involvement in many of the scandals and mysteries of the Victorian and Edwardian era. In “A Case for Langdale Pike,” I was, in effect, “playing the game.”

The “game”? As everyone in the BSI recognizes, Sherlock Holmes actually lived (so far as we know, he is still currently in retirement on the Sussex Downs, keeping bees and working on his masterwork, The Whole Art of Detection); his friend Dr. John H. Watson recorded actual historical events; and Arthur Conan Doyle merely served as Watson’s literary agent. While there may be confusions or discrepancies in the published accounts of the various cases, Irregular scholarship can fill in the gaps and harmonize the apparent inconsistencies. For example, to explain why Watson sometimes refers to being wounded in the left shoulder, and sometimes in the leg, at the battle of Maiwand in Afghanistan, Laurie King determined that the home made bullets used in Jezail rifles had a tendency to split apart. Hence one shot could produce wounds in two places.

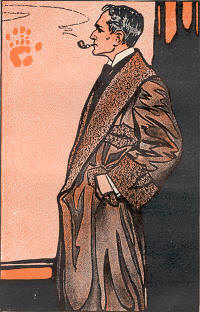

For me, this year’s 2012 BSI Weekend began on Thursday, January 12, when a small group met at The Players for “The Lunch of Steele,” a casual three-hour get-together in honor of Frederic Dorr Steele, the American artist who, early in the last century, gave us the most familiar images of Sherlock Holmes in his illustrations for Collier’s Magazine. That evening, Dr. Lisa Sanders, who writes the Diagnosis column for The New York Times and serves as a technical advisor to House, the Holmesian television series partly inspired by her column, delivered a lecture titled “Is Holmes Crazy Like a Fox, or Just Plain Crazy?” She explained that her early admiration for the detective’s logical reasoning led to her fascination with medical diagnosis. Later that night, at a “Special Meeting,” I was asked to speak about On Conan Doyle, my own new book about the Sherlock Holmes stories and his creator’s many other works.

That was just Thursday, a mere hors d’oeuvres for the continuous eating, drinking and conversation of the next two days. The main focus of the weekend remains the Irregulars-only black tie banquet (other Sherlockians attend the concurrent “Gaslight Gala”). Held this year at the Yale Club, the evening began when Michael Whelan—called “Wiggins” after the leader of the original Irregulars—announced and introduced “the woman” for 2012, a tradition dating back to the days when the BSI was all male. Nowadays “the woman” is often the surprised spouse of a particularly active male Irregular. But the first acknowledged recipient of the honor, back in 1943, was none other than Gypsy Rose Lee. This was in the same risqué era when mystery novelist Rex Stout—whose overweight detective Nero Wolfe just might be the son of Irene Adler and Holmes’s portly and smarter brother Mycroft—notoriously argued, amid much audience participation and outrage, that “Watson was a woman.”

This year’s dinner, by comparison, was a more sedate affair, though the drink did flow steadily during various toasts to Holmes’s landlady Mrs. Hudson, to Mycroft, to the second Mrs. Watson, and to Holmes himself. These were followed by the reading of the BSI’s constitutional “Buy-laws”—so spelled—which famously conclude: “Article 4. All other business shall be left for the monthly meetings. Article 5.”—and here everyone raucously joins in—“There shall be no monthly meetings.”

In the course of the evening, there were musical interludes, including a rendition of the BSI’s much-revered if unofficial anthem: “We Never Mention Aunt Clara.” The complete lyrics, relating naughty Aunt Clara’s sexual conquests, are always included in a special souvenir packet for each member attending the dinner. In this year’s I found, along with much else, the following: a ballpoint pen engraved with the phrase “This pen has been stolen from Mr. Sherlock Holmes.” An “Irregularly Shaped” crossword compiled by Dana Richards, the bibliographer of polymath Martin Gardner. (Gardner’s closest boyhood friend, John Bennett Shaw, was the greatest of all collectors of Sherlockian memorabilia.) A reprint of an American Philatelist article by Robert A. Moss about stamps honoring Holmes and Conan Doyle. The Christmas annual of “The Norwegian Explorers of Minnesota.” A postcard asking support for the campaign to save Conan Doyle’s former home Undershaw. A drawing by C.A. Meyer of “The Poodle of the Baskervilles.” And a small pin, in memory of Tsukasa Kobayashi, co-author of Sherlock Holmes’s London, displaying the address “221B” against a green background.

Advertisement

People sometimes wonder why I belong to The Baker Street Irregulars. The answer, of course, is elementary: friendship, collegiality, fellowship. For a few days, all that matters is one’s devotion to the great detective and his world. But it isn’t just Sherlock Holmes that we cherish, it is the memory of the pleasure we all received as children and teenagers when we first discovered those immortal adventures, when we first copied out the cipher of “The Dancing Men,” when, best of all, we first heard Dr. Mortimer murmur that most thrilling sentence in all of twentieth-century literature: “Mr. Holmes, they were the footprints of a gigantic hound!”

N.B. Authorized information about The Baker Street Irregulars may be found at the website of The Baker Street Journal. The Baker Street Blog is a good source for the latest Sherlockian news and comment.