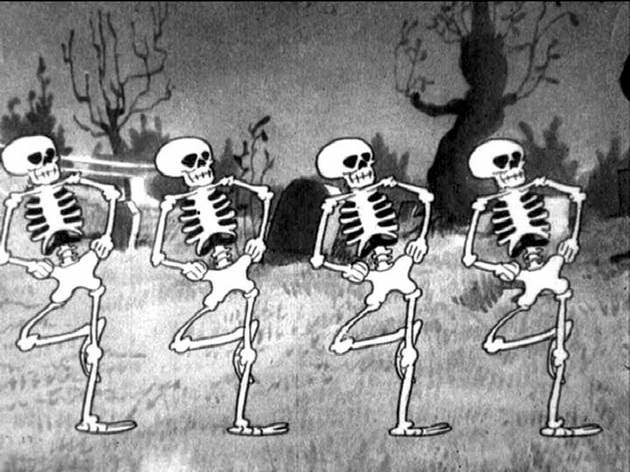

Not long ago, I found myself having a Twitter conversation with a rotating skull. Its picture shows a skull turning around and around against a black background. Its handle is simply @rotatingskull. Its self-description is cryptic: “I am a skull that rotates.” When I asked it how I might make my own head rotate in this attractive manner—something I have always longed to do, as it would be a visual description of my state of mind in the mornings before caffeine—it told me I should view The Exorcist backwards while sprinkling holy water. Then it sent me a YouTube of itself in younger days, when it still had a skeleton, featuring as the prima ballerina—or ballerino—in the 1929 Disney Silly Symphony, The Skeleton Dance.

“Impressively nimble,” I replied. Then I hesitated. Wait a minute, I thought. You’re losing all perspective. You’re talking with a skull. You have no idea who this is. Would you let a skull pick you up at a bus stop?

Definitely not. But on Twitter you find yourself doing all sorts of things you wouldn’t otherwise do. And once you’ve entered the Enchanted E-Forest, lured in there by cute bunnies and playful kittens, you can find yourself wandering around in it for quite some time. You might even find yourself climbing the odd tree—the very odd tree—or taking refuge in the odd hollow log—the very odd hollow log—because cute bunnies and playful kittens are not the only things alive in the mirkwoods of the Web. Or the webs of the mirkwoods. Paths can get tangled there. Plots can get thickened. Games are afoot.

When I first started Twittering, back in 2009—you can read about my early adventures in a NYRblog post I wrote two years ago—I was, you might say, merely capering on the flower-bestrewn fringes of the Twitterwoods. All was jollity, with many a pleasantry being exchanged. True, some of those doing the exchanges represented themselves in masks, or as pairs of feet, or as rubber ducks, or as onions, or as dogs—quite a few dogs. But having had an early career in puppetry and a somewhat later phase during which I amused small children by giving voices to the salt and pepper shakers, I was aware of the fact that anything can talk if you want it to. My Twitter friends were not only sportive but helpful, informing me about Twitpic, letting me in on the secrets of acronyms such as “LMAO,” analyzing the etymology and deep symbolic meaning of “squee,” and teaching me to make many an emoticon, such as the vampire face, represented thus: >:>} (Though other vampire-face options are available.) They led me to extra-Twitter adventures: a live chat on DeviantArt, a website where I found the cover for my book, In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination. To this day I rely on my Twitter followers for arcane information, most recently some updates on the vernacular speech of the young. Who knew that “sick” is the new “awesome,” and that “epic” is the rightful substitute for “amazing?” Twitter knew.

It was not long however before those with more serious purposes sought me out. Some were bent on my destruction, because I was a left-wing Red Emma, or, conversely, a wicked right-wing apologist for capitalism. Others wanted me to sign petitions or lend them support—all kinds of petitions, all kinds of support.

Signing petitions and lending support can get me into difficulties. One fracas—a “flame war,” Twitterers called it, appending gleeful LOLs—resulted in my writing an opinion piece for the Toronto Sun after it had attacked me on various fronts. In this piece I said I would vote for a turnip if it was “accountable, transparent, a parliamentary democrat, and listened to people.” I chose the Turnip rather than, say, the flighty Tomato or the flamboyant Squash, because turnips are modest, down-to-earth, and blunt-speaking.

Twitter and Facebook immediately wanted The Turnip to run for Prime Minister. It had a moment of fame, during which it got its picture taken in a fancy purple cabbage suit and red-framed glasses. But, being a vegetable and rather slow to act, it is still considering its options. It may yet get in by acclamation. And—BTW—it has had several phone calls from distraught Republicans of an older generation who long for the restoration of a more civil political discourse. The Turnip feels their pain.

More recently, Twitter involved me in the still-famous 2011 “War of the Toronto Library System.” This came about as follows. Toronto elected a mayor called Rob Ford, who promised to get rid of the gravy in the Toronto budget while avoiding both tax raises and service cuts. As this was not possible, he then proposed to raise taxes and cut services. Among the latter was the Toronto Public Library, much loved and much used in all areas of Metro Toronto—in fact, the most used system per capita in North America. I retweeted a petition about this, and so many of my followers piled onto it that it crashed the site.

Advertisement

A news item ensued, in which my name featured. The Mayor’s brother, Doug—a city councilor, and attached to the Mayor at the hip—stated he didn’t know what I looked like, and if I wanted to have an opinion I needed to get elected and go down to City Hall—a peculiar concept of free speech in a democracy. I was in the wild woods, out of e-contact, but when I got back it was to Atwood For Mayor graffiti and buttons, the news that a platoon of citizens had attended a City Hall meeting wearing printouts of my face, and many smiles and waves, and shouts of “Margaret! We know what you look like!” On Twitter, many Tweeted their happy, snuggly, or saved-my-life library anecdotes. The story shot around the world via social media and newspapers; the library and City Hall both were deluged with letters and messages; and councilors became quick to declare their enduring love for libraries. It’s clear from this and many more sharp-edged manifestations—such as Tahrir Square and Occupy Wall Street—that Twitter and its online siblings do not merely reflect the news: they also create it.

Which is why many governmental attempts are being made, globally, to curb, control, and curtail. The US’s proposed Stop Online Piracy Act, or SOPA, was draconian. Canada’s proposed Bill C30 would have permitted governmental e-snooping without a warrant. Both aroused so much online ire that their proposers are currently re-thinking. But ordinary folks should not have to choose between theft and Big Brother: surely the hive mind is creative enough to write its own fair rules, ones that protect both creators’ rights and consumer privileges. If it doesn’t write fair rules and enforce them itself, someone, sooner or later, will write unfair rules for it.

And we’ll all be less free if that happens. For the e-forest is not a street, nor is it a meadow. It is not yet tame. It’s still the merry wild greenwood, where—as in the plays of Shakespeare—enchantments may happen. True, there are sometimes trolls: that’s what makes the woods wild. And every sword has two edges, the one you cut with and the one that can cut you: no-holds I-spy cyber wars are raging up there in the Clouds. But cages for all would surely be worse. Anyway, on Twitter, there’s always the magic charm UNFOLLOW, and the even more dire BLOCK.

As for @rotatingskull, who knows what lurks behind that white, enigmatic, gently twirling facade? So far, only the Rotating Skull itself knows. On Twitter, playland of masqueraders, we are what we choose to divulge. Or to conceal. It’s nice to have some choice left, about something.