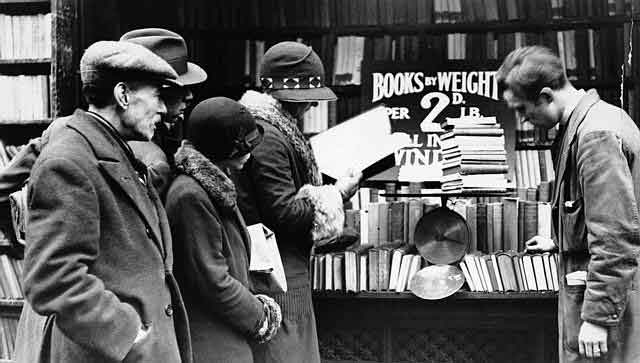

Used-book stores are disappearing in our day at an even greater rate than regular book stores. Until ten years ago or so, there used to be a good number of them in every city and even in some smaller towns, catering to a clientele of book lovers who paid them a visit in search of some rare or out-of-print book, or merely to pass the time poking around. Even in their heyday, how their owners made a living was always a puzzle to me, since typically their infrequent customers bought nothing, or very little, and when they did, their purchase didn’t amount to more than a few dollars. Years ago, in a store in New York that specialized in Alchemy, Eastern Religions, Theosophy, Mysticism, Magic, and Witchcraft, I remember coming across a book called How to Become Invisible that I realized would make a perfect birthday present for a friend who was on the run from a collection agency trying to repossess his car. It cost fifteen cents, which struck me as a pretty steep price considering the quality of the contents.

What made these stores, stocked with unwanted libraries of dead people, attractive to someone like me is that they were more indiscriminate and chaotic than public libraries and thus made browsing more of an adventure. Among the crowded shelves, one’s interest was aroused by the title or the appearance of a book. Then came the suspense of opening it, checking out the table of contents, and if it proved interesting, thumbing the pages, reading a bit here and there and looking for underlined passages and notes in the margins. How delightful to find some unknown reader commenting in pencil on a Victorian love poem: “Shit,” or coming across this inscription in a beautiful edition of one of the French classics:

For my daughter,

make beauty, humanity and wisdom

your lifelong objectives; and in all circumstances

you will know what to do. Happiness will be

the reward for your efforts.

One would either restore the volume on the shelf, or continue lingering over it and delaying the verdict. Of course, every now and then, there would come along some trashy book that one could not resist having, like the biography of Rudolph Valentino, the silent movie heartthrob, I bought last fall, which advertised itself as the sensational, never-before-published truth about the most fiery sex god of our time, and promised to reveal why his first wife left him before dawn on their wedding night.

However, other times there’d be a book I’d start reading and couldn’t put down. Here, for example, is the opening of one called Business be Damned—not a very promising title—by someone called Elijah Jordan, published in 1952 by Henry Schuman, New York, and presented at some unknown date to the library of Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas by its original owner, Dr. Joe Colwell, and subsequently removed from their collection:

There have always been businessmen and business in the world. But never in history till today was business accepted as a morally honorable activity for men; never before was the businessman permitted to dominate the affairs of men. Today the rule of the businessman, accepted, justified and glorified, has become undisputed and absolute.

Until lately, however, the activity of the businessman has always been questioned as to its moral rightness. The formulation of this doubt has been the negative or critical premise upon which every developed moral system and every cultured religious system has been founded. The new fact, therefore, in what is called modern civilization, is the acceptance of business activity as morally honorable, the approval of the capacities and the characteristics of the businessman, and the assumption that these capacities are appropriate for rule and control of human affairs.

This is extraordinary, I said to myself. Jordan (1875-1953), who was a professor of philosophy at Butler University for many years, saw the writing on the wall, pointing out already back then that business had become the dominant force in our lives with all other human interests in this country subservient to it. Religion, politics, government, morality, art were all being asked to acknowledge its absolute right and absolute power to be the final arbiter.

If he came back from the dead today, Jordan would be surprised that his fellow Americans still haven’t caught on that they are being taken to the cleaners. On the contrary, many of them now believe that the solution to all our problems, be it failing schools or expensive healthcare, is to hand over every publicly run institution to profit-seeking private companies, which, thanks to their knowhow and the magic of the free market, will save tons of money for the tax payers. This is what is known as “privatization” today, the scam that makes everything from private prisons, the vast growth of our surveillance state, and our global military presence, a hugely lucrative enterprise. Voters, one can’t help but conclude, no longer seem to have any problem with fortunes acquired dishonestly and at their expense, some of them even going into huge debt to send their sons and daughters to prestigious business schools so they can go to work for these hucksters and emulate their success.

Advertisement

After the demise of used-book stores and libraries, what are the chances that someone will come across a book like Jordan’s? That there are others like him—a few known and others completely unknown—I have no doubt. Not that he and these other truth-tellers made much of an impression on their contemporaries, or on later generations of Americans who’d rather hear fairy tales about us being the envy of all creation, unique as a nation, a country of unlimited potential and opportunity, best in everything, rather than have some loser tell them otherwise. No wonder their books are doomed to perish in the coming years. The fate of these forgotten writers is a sad reminder that this will also happen to many serious works of philosophy, history, fiction, poetry, and all the other books collecting dust on their shelves. As long as they were there, some browser with plenty of time on her hands would have a chance to find a phrase, a bit of description or some little story in one of them, that enriches her life and does her soul good.