There is nothing more mysterious and wonderful than the way in which some bit of language—a clever quip, a pithy observation, a vivid figure of speech found in a book or heard in a conversation—remains fresh in our memory when so many other things we were at one time interested in are forgotten. These days, I look in disbelief at many of the books on my shelves, from thick novels and memoirs to works of great philosophers, wondering whether it’s really possible that I devoted weeks or even months reading them. I know that I did, but only because opening them, I find passages and phrases I’ve underlined, which upon rereading I recall better than the plots, characters, and ideas I encountered in these books; sometimes it looks to me that what has made the lasting impression on my literary taste buds, to use culinary terms, are crumbs strewn on the table rather than the whole meal.

I recall, for example, Flaubert saying that it is splendid to be a writer, to put men into the frying pan of your imagination and make them pop like chestnuts; St. Augustine confessing that even he could not comprehend God’s purpose in creating flies; Beckett telling about a character in his early novel Murphy whom the cops took in for begging without singing, and who was jailed for ten days by the judge; Victor Shklovsky, recounting how he once heard the great Russian poet Mayakovski claim that black cats produce electricity while being stroked; Emily Dickinson saying in a letter, It is lonely without birds today, for it rains badly, and the little poets have no umbrellas; Flannery O’Connor describing a young woman as having a face as broad and as innocent as a cabbage and tied around with a green handkerchief that had two points on the top like rabbit ears; and many other such small and overlooked delights.

Examples of verbal art, of course, are not only to be found in books. One of the most original and entertaining story tellers I ever met was an old Sicilian bricklayer whom I knew in New York more than forty years ago. He’d talk in images: “I came out of the crib gray-haired,” he’d say, or “Every four years we change the president’s diaper.” Writers and conversationalists with a gift for nailing a subject or someone’s character quickly know that a lengthy description is not likely to be as effective as a single, striking image. “What the mind sees, when it grasps a connection, it sees forever,” Roberto Calasso says. “His wife looks like a stork,” I overheard someone say in a restaurant and my imagination swallowed the bait. She’s tall, long-legged, wears short skirts, holds her head high, and has a long thin nose, I said to myself. And that was just the beginning. The day after I heard a wife being compared to a stork, I saw her standing on one leg on top of a brick chimney and then a bit later perched on a gravestone in a small graveyard.

That gravestone reminded me of something crazy the poet Mark Strand thought up many years ago, when he was broke and thinking up ways to make money. He told me excitedly one day that he had invented a new kind of gravestone that he hoped would interest cemeteries and carvers of gravestone inscriptions. It would include, in addition to the usual name, date, and epitaph, a slot where a coin could be inserted, that would activate a tape machine built into it, and play the deceased’s favorite songs, jokes, passages from scriptures, quotes by great men and speeches addressed to their fellow citizens, and whatever else they find worthy of preserving for posterity. Visitors to the cemetery would insert as many coins as required to play the recording (credit cards not yet being widely used) and the accumulated earnings would be divided equally between the keepers of the cemetery and the family of the deceased. This being the United States of America, small billboards advertising the exciting programs awaiting visitors to various cemeteries would be allowed along the highway, saying things like: “Give Your Misery A Little Class, Listen to a Poet” or “Die Laughing Listening to Stories of a Famous Brain Surgeon.”

One of the benefits of this invention, as he saw it, is that it would transform these notoriously gloomy and desolate places by attracting big crowds—not just of the relatives and acquaintances of the deceased, but also complete strangers seeking entertainment and the pearls of wisdom and musical selections of hundreds and hundreds of unknown men and women. Not only that, but all of us who are their descendants would spend the later years of our lives devouring books and listening to records, while compiling our own little anthologies of favorites.

Advertisement

While this invention may strike one as frivolous and irreverent, in my view it deals with a serious problem. What happens to everything we kept in our heads and hoped others would find amusing after we pass away? No trace of them will be left, unless, of course, we write them down. Even that is not a guarantee. Libraries, both private and public, are full of books no one reads any more. Anyone who frequents town dumps has seen yellowed manuscripts and letters thrown out with the trash—papers that sadly, but unmistakably, not even the family of their author wants. Just imagine that Strand’s dream had come true and your dead grandmother is a big hit in some large urban cemetery, passing on her soup and pie recipes to an admiring crowd of young housewives; while your grandpa is telling dirty jokes to boys playing hooky from school. Given their immense local fame, you, too, are regarded with interest by your friends and neighbors, who can’t help but wonder how your everlasting selection is coming along and what inspiring words and vile blasphemies they’ll be hearing from your gravestone.

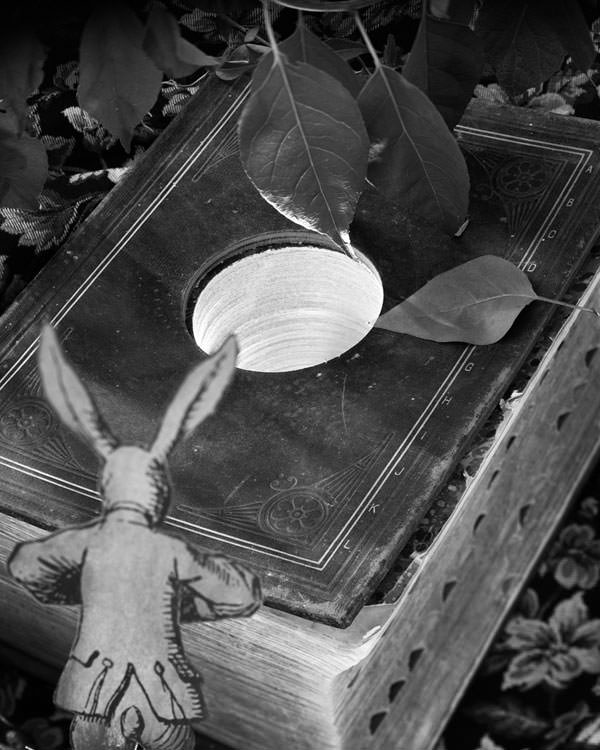

A retrospective of Abelardo Morell’s work, “Abelardo Morell: The Universe Next Door,” is on view at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, February 23-May 18, 2014; a catalog of the exhibition was released by the Art Institute of Chicago and Yale University Press last fall.