I was faintly apprehensive when I clambered up the curving staircase of the Courtauld Gallery to see “Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album.” Outside, in the courtyard of London’s Somerset House, the fountains were flashing in clear April sun: approaching these drawings of magic, madness, and age I was leaving spring for autumn and winter, going into darkness, inside Goya’s imagination—not a place I was sure I wanted to be. But as soon as I was face to face with his powerful, irreverent sketches, I was both horrified and entranced. The small dancing figures linger in my eye. Once seen, never forgotten.

The sketches themselves tell a story of survival, with strange twists and turns. Over thirty-five years, from around 1794, when Goya, still in Madrid, was recovering from the devastating illness that left him permanently deaf and forced him to abandon grand court painting, to his death in Bordeaux in 1828, aged 82, he put together a sequence of eight “albums” of brush and ink drawings. Often he added a laconic, ironic caption in black chalk. After his death the books were unbound and over time many images were scattered. Despite this, experts have been able to calculate the contents of each of the albums (which have been lettered A through H).

The Courtauld show reunites all twenty-two drawings, gathered from private and public collections, from Album D, the “Witches and Old Women” album. It’s an ambitious project, the first time this has been done. (A fascinating essay in the catalog describes the technical research behind this reconstruction.) Most of the drawings date from 1819 to 1820, when Goya was in his early seventies. In 1819 he had bought his house in the country, where he covered the walls with his terrible “Black Paintings,” like Saturn Devouring his Son, full of the fear of madness and the cruelty of the world. The “Witches and Old Women” album provides a key to his dark imaginings. These are private drawings, seen by a few friends, in which Goya could be rude, macabre, bitter according to mood, unfettered by constraints of patrons or politeness. The captions are minimal: “Monk,” “Nothing is known of this,” “I can hear snoring.”

These eerie sketches are unfamiliar, which makes them all the more intriguing. Better known works come from the second Madrid album, several of whose fantastical drawings—“Sueños” (“Dreams”)—attacking ignorance and intellectual prejudice, corruption and superstition, were later etched as Los Caprichos. The most famous, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, with its sinister owls and bats swooping up from behind the dreamer, is displayed here to give a context to the beginnings of Goya’s experimental, reflective graphic work, and its later development. Other Caprichos surround it, including the naked witches on their broomstick and the ghastly trio of old women spinning, like the Fates, with a bunch of tied-up babies behind them.

Moving into the room devoted to the “Witches and Old Women” album, single figures, or groups of one or two, rarely more, float on the page, with no setting behind them, the brushstrokes swirling and darting, as if alive. It isn’t only the witches—the dark, demonic cast—who are horrifying but the whole chorus of the aged, clinging to life. The small faces, brilliantly drawn, reveal bony bumps of skull, thinning hair, toothless jaws, furrowed brows. Gender vanishes—it’s hard to tell a decrepit, balding man from an old crone. Death is near: you can smell sickness.

Most of Goya’s witches are female, with one or two men as partners, or victims. They fly, copulate, and struggle in the air, as in They descend quarrelling, where one airborne hag drags her screaming opponent by the hair. They play their tambourines and flutes, as in old Inquisition accounts of witchcraft trials, magical music for a deaf man. There is nothing here so bitterly harsh as his earlier Disasters of War etchings, made in response to the devastation of the Napoleonic Wars, but ghoulish visions do appear. Witches carry off their prey, like the dark-browed woman in Unholy Union, striding toward us, gripping a man bound with snakes on her strong shoulders. There are gruesome allusions: newborn babies tied to poles; a bald, grinning witch all set to gnaw an infant’s limb. A man awakes kicking from his dreams, mouth open, limbs twitching. Elsewhere, in a drawing simply captioned “Nightmare,” a figure hurtles downward from a great height, hair on end. Is this Goya himself?

Mysterious as the drawings seem, his friends would have picked up the references. Several are openly anti-clerical—a monk or priest in cap and bells, the costume of a traditional fool. Others feature the old procuress, Celestina, a figure of Spanish comedy since the late fifteenth century, fingering her rosary while she swills down the booze. Yet Goya does not always associate piety with Celestina-like hypocrisy. He can be touchingly compassionate, as he is in She won’t get up till she’s finished her prayers, the sketch of an old woman intent on her rosary, the placing of the drawing low on the page making her seem lost in her isolation. The skill in this unassuming study is extraordinary, the light bathing her cape from above, the shadow of her hood over her brow, the focus on her hands and beads.

Advertisement

Not all old women are witches. Goya’s old biddies can be exuberant. They argue and tussle and push. They talk fondly to their cats. Though scrawny and bent, they still dream of marriage. They sing and dance and lust. A woman in the frilly carnival dress of an Andalusian gypsy sails off the ground, strumming her guitar and belting out a song, while another below, dressed as a nun, peers up her petticoats, smiles and holds her nose. Nearby, an upright pestle protruding from in its mortar adds sexual to scatological innuendo. Two comically deft studies in the introductory room applaud lively old age. In Content with her lot, an old woman clicks her castanets and dances with her shadow. In Showing off? Remember your age, she tumbles down the stairs, legs in the air, stockings awry, a would-be acrobat gone wrong.

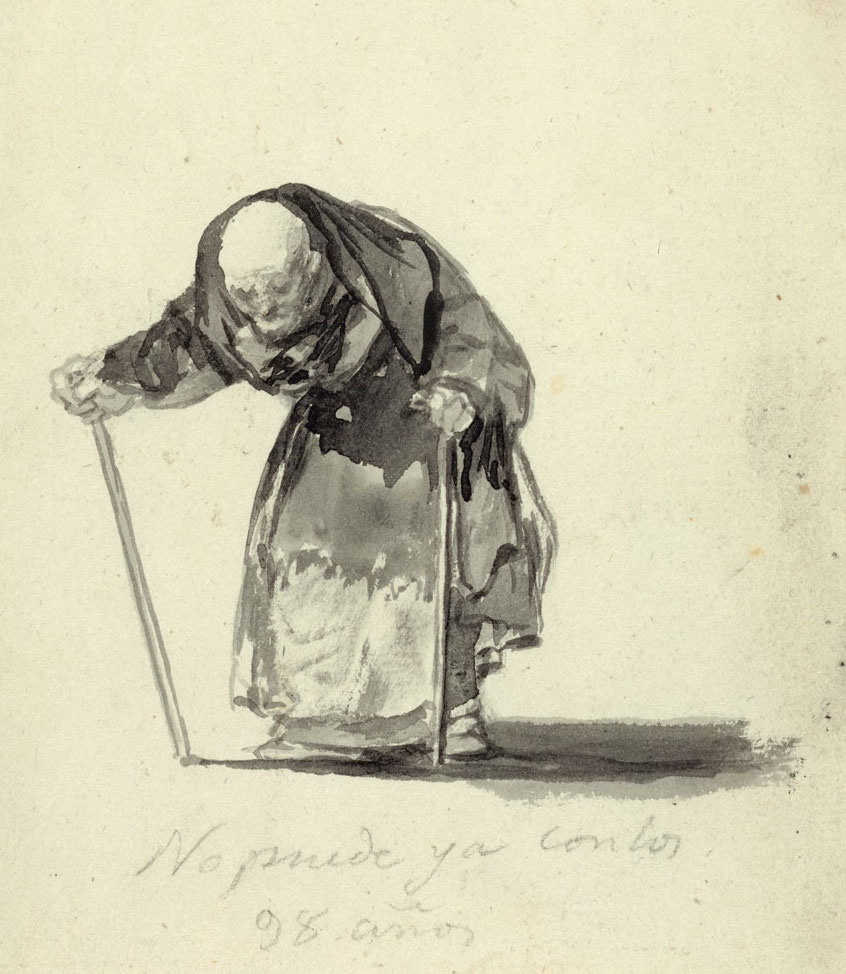

One of the most disturbing elements in the witches sequence is their weightlessness. Like the old gypsy singer, they lose touch with solid ground, as if cut free from sense, reason, comfort. Instead they soar into the sky or plunge into the depths. These sketches were drawn in an uncertain time, when Goya was filled with doubt about his own old age and angry despair about the future of his country: he would leave Spain for good in 1824, moving to Paris, and ultimately Bordeaux. In France he filled a final two volumes (albums G and H), with yet more sketches of age and sensuality, madness and vanity, their subjects, like the ancient winged couple of They love each other very much, still swirling up into the skies. Goya’s drawings may leave us too, up in the air, filled with a disquieting unease. Yet in the end, the witches and old people are tokens of life, not death—even the tired, ancient man shuffling on his sticks, mockingly captioned Just can’t go on at the age of 98. Evil they may be, black at heart, but they won’t relinquish their hold.

“Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album,” is on view at the Courtauld Gallery in London through May 25.