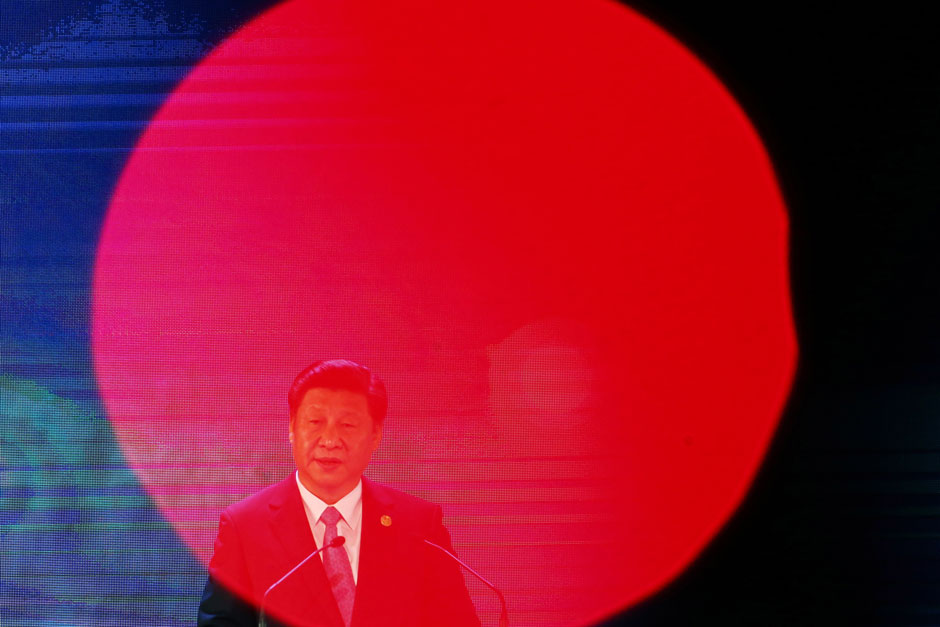

Xi Jinping is often described as China’s most powerful leader in decades, perhaps even since Mao. He has been credited—if sometimes grudgingly—with pursuing a vigorous foreign policy, economic reforms, and a historic crackdown on corruption.

But as Xi completes his third year in office this month, this judgment seems increasingly mistaken, with China trapped by the same taboos that limited Xi’s predecessors. At heart this means a one-party state unwilling to retreat from the commanding heights of the country’s economic, political, and social life. The only area where the government has shown real creativity has been in coming up with new ways of legitimizing its rule—diversions from the real issues facing the country.

This is all the more striking when we consider that Xi is now probably at the peak of his power. He took office as general secretary of the Communist Party and head of the central military commission on November 15, 2012; by now it is no longer useful to think of Xi as a new leader who needs time to implement his ideas. Instead, we have to recognize that he is already reached his point of maximum influence. By the second half of next year, factions will be jockeying for the 19th Communist Party Congress in 2017, which is when Xi’s successor will be picked—the two will serve together for the following five years, just as Xi served under Hu Jintao from 2007 to 2012. (An aside: the iron logic of these dates calls into question the oft-stated claim that China’s leaders are operating on some sort of visionary long-term horizon; instead, they have a political shelf life about equal to most Western leaders.)

But rather than significant innovation, Xi’s overriding goal seems to be preserving the ossified system he inherited when he came to power in 2012. Fundamentally this means state control over most of the economy and society. The state dominates the most important industrial sectors, especially heavy industry and natural resources. The state controls political life and permits no meaningful dissent. The state guides social life. It allows non-governmental organizations but only as providers of services, not as advocates of social change. The idea of a vibrant, critical civil society is unacceptable. As technological innovations arise, for example in social media, free zones may appear, but the state will do everything in its power to close these down.

From the time of his first major appointment in 1982, Xi has worked as a politically savvy organization man. His goal has been to recreate the early years of Communist rule in the early to mid-1950s when his father was part of the ruling elite. Back then, according to official mythology, the party was clean and officials were upright, and the populace was content. Returning to this imagined past means strengthening, not weakening party control.

If we briefly survey Xi’s actions over the past three years, we can see this as the primary goal of his reforms. Most obvious and probably the most disappointing for optimists is the economy. A year after Xi took power, he unveiled an economic reform plan that some heralded as the most ambitious since Deng first announced economic liberalization in the late 1970s.

But three years on, most of Xi’s changes—such as incremental bank rate liberalizations or opening the stock market a bit wider to foreign investors—can more properly be viewed as technocratic tinkering. It’s true that a lot of small repairs can lead to an overhaul, but only if the changes are part of a broader plan with a clear goal. There has been no indication that such a plan exists—at least not one that would lead to a more open economy.

It is possible that Xi might reverse course—perhaps the slow growth rate will force his hand—but signs are not promising. A recent, outstanding piece of fly-on-the-wall reporting in The Wall Street Journal shows that despite Xi’s anger about the slowing economy, the slow growth itself has made him cautious and even less willing to push reforms.

On social policy, too, true innovations have been illusory. The change of the single-child policy to a two-child policy has grabbed headlines, but means little to most Chinese. Many were already able to have two children (because they flouted the rules or live in rural areas or belong to ethnic minorities) and many more find it too expensive to do so. Instead, it might be useful to take officials at their word: back when the one-child policy was implemented it was supposed to be for thirty years and now that period is up. Given the demographic challenges facing the country, relaxing the policy slightly is more of a tweak than a revolution.

Advertisement

In other areas, such as rule of law, or registering NGOs, the policy is similar to the economic reforms: minor adjustments that will streamline the existing system and attract media attention, but not challenge state control.

What of Xi’s crackdown on corruption? On one level, the change is very real. More people, and more senior people, have been arrested than ever before. You can see this even among low-level officials far from Beijing, who are newly wary about going out to lavish banquets or driving cars that they probably shouldn’t be able to afford. An official I know in Shanxi province, for example, has completely stopped going out to eat on weekdays because he is petrified of being accused of a spendthrift lifestyle. Recently, his daughter got married and he insisted she do so in a low-key ceremony with just a few dozen guests—instead of the few hundred that he would have invited a few years ago.

But the very fact that this is being pursued through a “campaign”—rather than by legal reforms or by the creation of more independent controls on government—reveals its limits. For Xi’s anti-corruption program to lead to a cleaner society over the long term would require reforms to create an independent judiciary. Some reforms have been touted, but they are mainly to make the current system slightly more efficient. The Party’s control over the legal system remains intact. This makes it impossible for investigators, prosecutors, and judges to pursue corruption in a sustainable fashion. (And without even a partially free media, corruption often cannot be brought to light.)

By contrast, the government has been adept at finding fresh sources for its sweeping authority. One way has been to build support through nationalism and foreign adventures, such as the reef-building exercises in the South China Sea. Less obvious but possibly more effective has been to sympathize with popular discontent about immorality in society, and support traditional values. It has tried achieving this by blending Communist and traditional virtues into a new paradigm of the upright officials and the moral citizen. This gives primacy to traditional virtues, such as filial piety, thrift, and charity, while suggesting that communism shares these values. In one folk art propaganda campaign that has been running for two and a half years, for example, traditional handicrafts—clay figurines, paper cuts, and landscape paintings—are melded with slogans like Xi’s signature “China Dream.”

This is also apparent even at the most grassroots levels of cultural life. Old Ma, a friend of mine in Beijing, is a retired carpenter who makes beer money by singing traditional ballads. One explains how the gates of the old city got their names, while another tells the history the old town’s famous products: cloth shoes, herbal medicines, kites, roast duck, and double-distilled liquor. One day, he sang me a new tune.

On Marco Polo Bridge

Japanese bandits came

To take this land

But their plans were in vain

This struck me as strange and I asked him where he had learned it.

“It’s an old rhyme but the words are from the Xuanwumen Cultural Bureau. We’re going to perform it in public. We have five or six performances lined up. Three hundred yuan each!”

We were speaking in June, and the government was going to celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the end of the war in early September. Even now, months after the anniversary, China is blanketed in patriotic propaganda. Why would a district cultural office bother writing a song for a couple of retiree street musicians to perform when it had already saturated the country with heroic images?

“Does anyone notice the official propaganda anymore?” he answered. “So here’s some money for us to sing a few patriotic songs at the theater. When we sing it, people listen because they don’t expect it.”

The more I thought of it, the cleverer it seemed. Old Ma and his partner perform at little halls in Beijing’s theater district, or at private events in companies. In this sort of intimate setting, people’s ears are open, and less likely to block out the background noise of a propaganda campaign.

But I can also see the effect of this strategy on Old Ma. In the past, his singing was a genuine passion, something he did in parks and occasionally for money. Now, it has become a business, with the sole paying customer being the state propaganda apparatus.

In recent weeks, when I run into him, he talks about scoring big contracts worth tens of thousands of dollars to perform a series of pieces written by government hacks. He is now working on pieces for Chinese New Year in February. Few of them are overtly political, but as he noted to me last week, all are apolitical and meant to glorify the state.

Advertisement

“I guess it’s a form of stability maintenance,” he said, using a government term, weiwen, that has gained currency over the past decade. “People listen to this, they’re happy, you say the government is good, but mainly they don’t think of other things.”