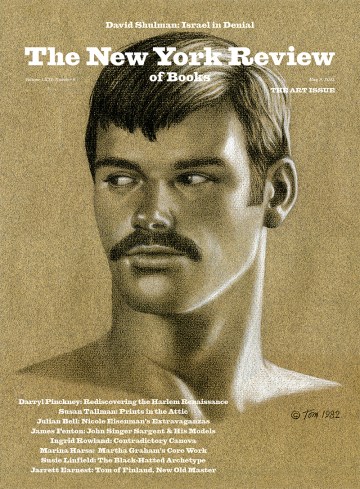

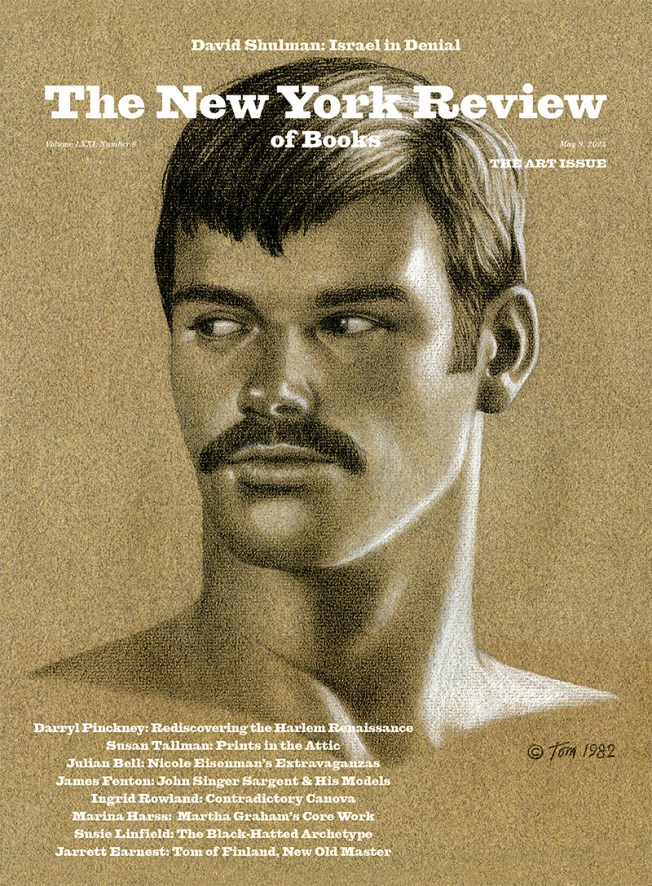

Danny Lyon’s still pictures—the work for which this restless photographer, filmmaker, and writer has always been best known—often center on people hanging out and killing time. Since 1962, when he hitchhiked from Chicago to segregated Illinois to take the first of the incendiary civil rights protest photographs that earned him his initial acclaim, Lyon has spent much of his career making intimate images of marginal, working-class, and outlaw communities. Many of the most striking pictures in the Whitney Museum’s new survey, “Danny Lyon: Message to the Future,” organized by the San Francisco-based curator Julian Cox and overseen by the Whitney’s Elisabeth Sussman, come from these milieus: in one characteristically unhurried shot, two New York City construction foremen lean against the sides of a narrow doorway smoking; in another, a roomful of prisoners pose for the camera—a crowded image in which the central figure is a young, handsome man reclining in a chair, his shirt half-open and his chin turned up. But the greatest revelations in the show come from another body of Lyon’s work Cox and his collaborators have prominently featured—his little-known documentary films.

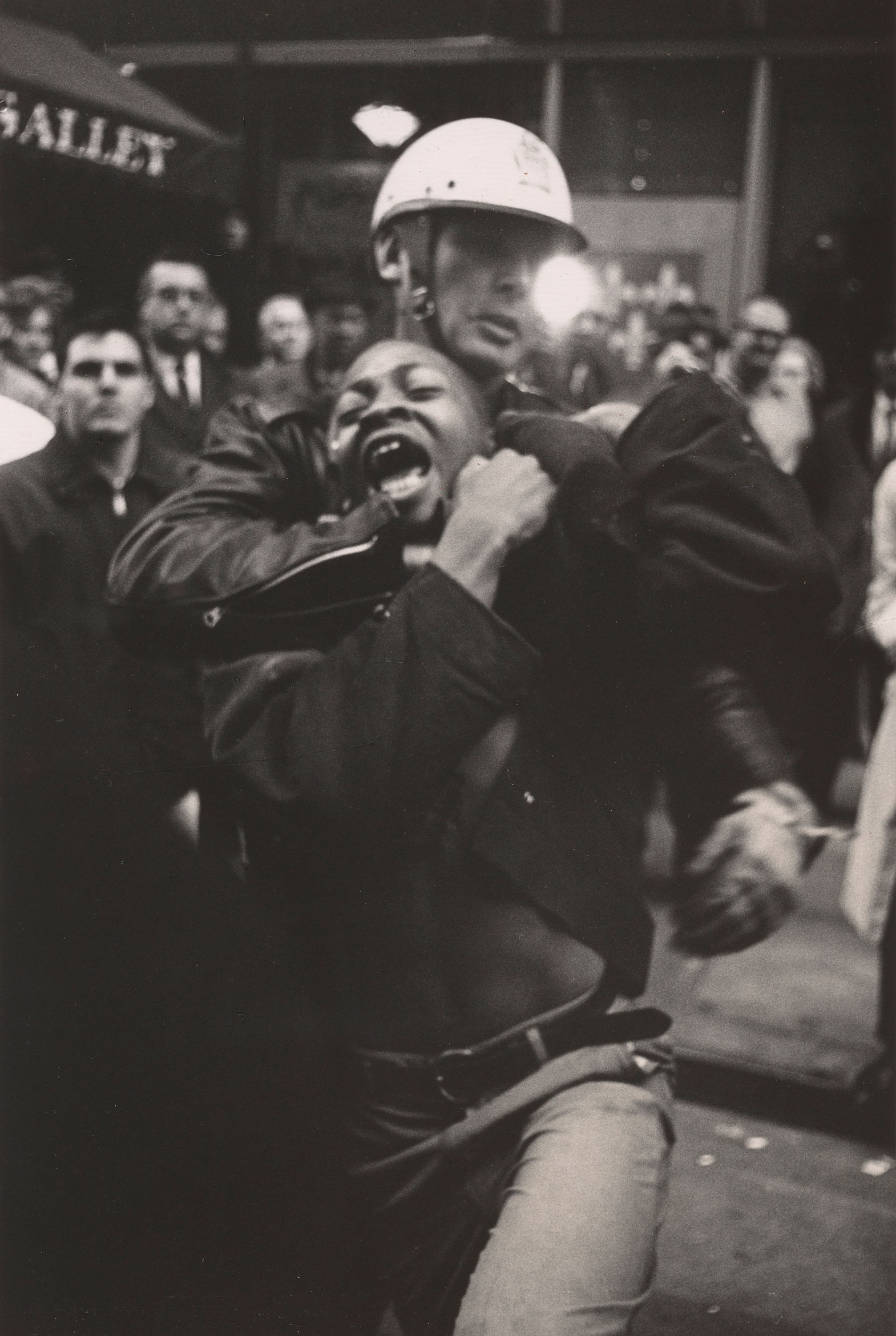

Lyon has always taken risks to earn the status of sympathetic insider in the communities he shoots. The photographs he took across the South in his early twenties were forceful enough visions of outrage and disgust—a group of young black women languishing in the Leesburg stockade; a protestor splayed out in midair as the object of a violent tug-of-war contest between an onlooker and a pack of riot police—that the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) soon made Lyon their staff photographer. (One of his pictures, of a grim-looking cop crossing his arms, appeared on the organization’s posters emblazoned with the slogan “Is He Protecting You?”) Lyon would never align himself so completely with another group’s mission and goals, but most of his subsequent projects have involved a similar degree of intense, life-consuming commitment. To make The Bikeriders (1968), the first book of photographs for which he had sole credit, he spent a year as a member of the Chicago Outlaws; for Conversations with the Dead (1971), his third book, he lived in Texas for still longer taking pictures in the state’s prisons.

Between 1965 and 1973, he photographed poor Appalachian transplants in Chicago, prostitutes and homeless children in Santa Marta, Colombia, trans women of color in Galveston, and undocumented workers in New Mexico, one of whom he helped cross a roadblock while the two of them were building an adobe house. For his picture of a man straddling a prone, semi-nude woman in a field while three bikers crouch predatorily around her—an image included in The Bikeriders but not in the Whitney show—students at Hampshire College accused Lyon of condoning rape. “It made me sick too,” Lyon told Nan Goldin in a 1995 interview for Artforum. But “at that time I thought of myself as a journalist, and when you’re a journalist you intentionally place yourself in situations where most people aren’t, because you’re a kind of witness for them.”

A deeply ingrained curiosity; a readiness to put himself in dangerous or unfamiliar settings; a sometimes ethically perilous refusal to judge—the qualities that emerge in Lyon’s work on view at the Whitney make one wonder how he gained the degree of confidence with his subjects he seems to enjoy. How did this middle-class interloper, who grew up in a German-Jewish family in Queens, get so close to such a range of people predisposed not to trust outsiders? Looking at many of the photographs in the show, you find yourself speculating about the efforts it must have taken Lyon to cultivate a trusting, comfortable rapport with these people—efforts on which the photographs depended but about which they themselves tend not to reveal much. More than the pictures themselves, it’s Lyon’s sixteen nonfiction films that show how his relationships with his subjects have developed haltingly and sometimes tensely over time.

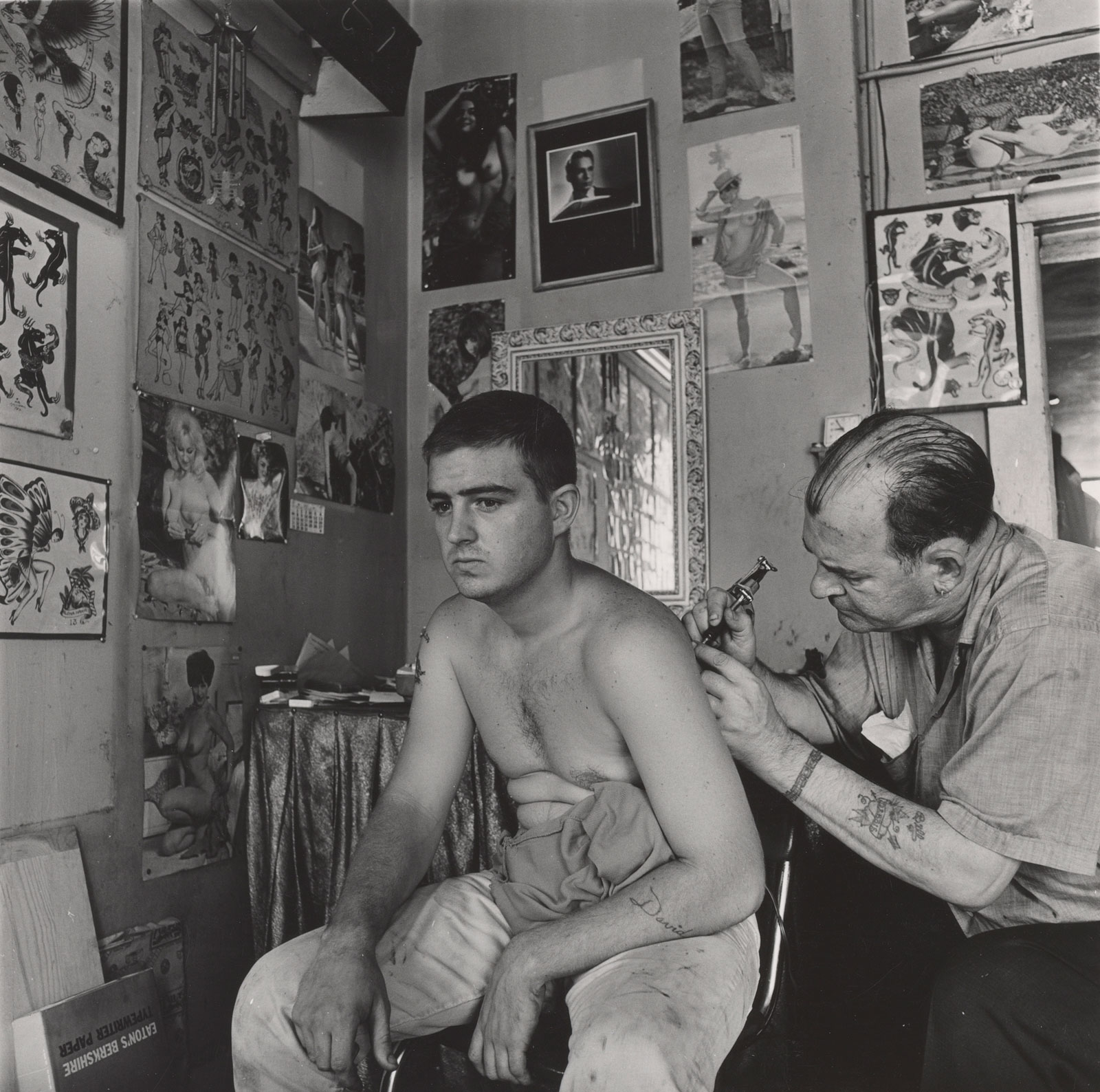

Lyon made Soc. Sci. 127 (1969)—the mischievous study of a Texas tattoo artist that became his first film—using a borrowed 16mm camera and an editing machine he shared with his friend and roommate Robert Frank. As he’d tell Goldin in the Artforum interview, he had just finished Conversations with the Dead and “couldn’t think at the time of how to go beyond” that book. (“I’d put everything into it but live flowers.”) Lyon has kept making photographs over the past three decades—of New Jersey speedways; of coal workers in China; of young men in a not-yet-gentrified Bushwick—but since the early Seventies his films have taken up much of his energy. For Lyon, filmmaking has become a chance to capture the drift and tempo of the hangout sessions, conversations, and daily interactions from which his photographs come.

Advertisement

Character portraits of irregular lengths and digressive shapes, Lyon’s films have never enjoyed as bright a profile as his photographs. And yet they are secret treasures of nonfiction cinema—plainspoken, offhandedly beautiful, rich, and troubling in what they suggest about the filmmaker’s relationship with his subjects. Like Lyon’s photographs, these movies consist largely of characters rambling, whiling away time, and going about their business seemingly unhindered. For the homeless children at the center of Los Niños Abandonados (1975), which Lyon shot in Santa Marta, that business involves sleeping outside churches, collecting leftovers from the tables of cafes, swimming in rivers and cooking what look like chicken feet.

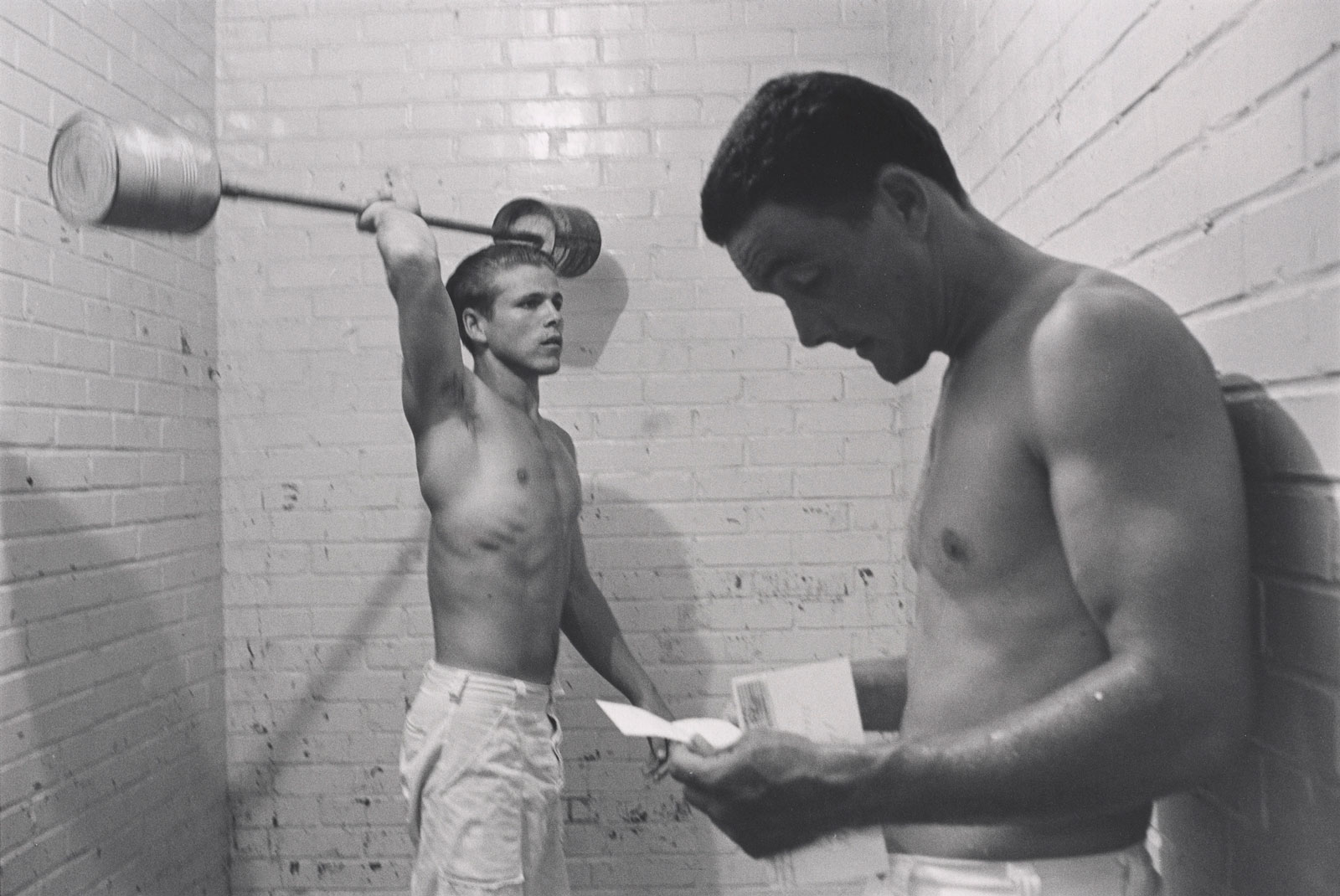

The primary characters in Willie (1985), some of whom Lyon earlier filmed in Llanito (1971) and Little Boy (1977)—a mentally unstable New Mexico ex-convict named Willie Jaramillo, his brother, his young nephew, and the prisoners with whom he served time—spend the film riding in pickup trucks, listening to music, and, in the case of the inmates, lifting weights in a break room Lyon depicts as a chaotic, noisy social center. (The Whitney is showing Willie, Soc. Sci. 127, and Dear Mark (1981), a jokey short view of Lyon’s friend Mark di Suvero making one of his large sculptures, looped in two cordoned-off rooms.)

El Otro Lado (1978) follows a cluster of undocumented migrant workers from their hometown in Mexico to an Arizona farm, where they pick lemons and oranges, sleep in fields, bathe in concrete irrigation ducts and make border crossings in what are actually— we only learn in the film’s closing credits—re-enactments performed by the men themselves. Several of Lyon’s films playfully incorporate fictional elements like this or skip unpredictably back and forth in time. At no point in Soc. Sci. 127, for example, as the critic and curator Ed Halter notes in the Whitney exhibition catalog, are we told that the scenes that bookend the movie of a tattooing class are staged.

With the exception of Willie’s black-and-white flashbacks to Lyon’s earlier footage of its protagonist and the staged scenes in Soc. Sci. 127, these four movies are shot in vivid color, a striking contrast with the sunlit black-and-white that predominates in Lyon’s early photo books. Lyon’s growing interest in color photography, in the mid-Sixties, slightly predated his turn to filmmaking. In 1966 he took a number of magisterial color pictures within and around Colombian brothels, one of which—a portrait of a woman in a bright red dress and matching lipstick squinting into the camera with regal stoniness—the Whitney has chosen in its promotional materials as a kind of emblem for this retrospective.

To a viewer familiar with Lyon’s photographs, what’s startling about the films is their heightened element of tension—their sense that Lyon’s trust with his subjects hasn’t yet hit a stable form. What the critic Belinda Rathbone wrote about Willie in a 1986 article for Aperture applies to several of Lyon’s movies: that it bears “signs of rejection” that his early photographs rarely showed. That film’s title appears over a shot of a hand covering Lyon’s camera, and one of the dominant impressions the film leaves is of Willie’s paranoid distrust over being filmed. When he’s onscreen, his eyes often dart around as if in search of exit routes.

The interview scenes in Los Niños Abandonados often show the movie’s young characters in close-up, visibly uncomfortable, mumbling brief replies to questions they’d rather not answer about their families and pasts. In the autobiographical, essayistic Born to Film (1982), a similar sense of unease pervades Lyon’s conversation with Billy McCune, the psychologically troubled prisoner whose drawings and writings had a central place in Conversations with the Dead. Filmed during McCune’s visit to Lyon’s home in 1982, eight years after his release from prison, the pair’s talk comes off as strained and hesitant. When Lyon intercuts footage of this interview with shots—in fact taken on a different day—of a group of children playing naked in his backyard, it’s as if he’s exchanging his nonjudgmental earlier persona for that of a suspicious, protective parent.

Lyon’s wary tone in that scene is atypical. More often, the energy and drama of his movies come from his efforts to get closer to people who seem to be resisting, evading, or ignoring him. The subjects of Lyon’s early photographs often made charged, direct eye contact; in one of his most arresting portraits, a Chicago woman named Kathy locks eyes with the camera boldly and a little flirtatiously. In contrast, for long stretches of some of his films, including El Otro Lado, his characters barely acknowledge his presence. Intimacy is sporadic and hard-won.

Advertisement

When such moments of intimacy do emerge in these films, they often come by way of group activities—games, dances, songs—with agreed-upon and consistent forms. The field workers in El Otro Lado spend their free time playing cards, and one fragment of the 16mm footage Lyon filmed in the Texas prisons (never publicly exhibited until now) shows inmates playing dominoes. The ribald group sing-alongs that fill El Otro Lado and the ballads that punctuate Los Niños Abandonados—sung directly to the camera by the boy who composed them—are crucial to those movies’ emotional texture, just as the scene of Willie sitting under a bridge in his underwear singing the spiritual “When the Roll is Called Up Yonder” inspires one of his most tender interactions with Lyon in the film he inhabits.

Not all of Lyon’s film work concerns particular characters and communities. He has also made forthrightly autobiographical movies like Media Man (1994) and Born to Film, for which he intercut clips of his young son with footage his father took of him during his own early childhood. Recalling the scrapbook-like photo collages—he calls them “montages”—Lyon has made since the late Sixties, Born to Film is a poignant glimpse of the home life Lyon has sustained amid many trips and re-locations. But it’s pictures like the ones in Conversations with the Dead and films like Willie and Los Niños Abandonados that best suggest what makes Lyon such a thrilling artist: his intense impulse to familiarize himself with lives wildly different from his own.

By Lyon’s own account, this has come in part from an acute feeling of personal responsibility toward his subjects. In his 1999 autobiography Knave of Hearts, Lyon described visiting Willie one day in the mid-Seventies and finding him “a sad and lost young man.” With the camera running, Willie

talked about living in a cabin with a girl and having her read the Bible to him every night. When he turned to me and said, ‘This is my life we’re talking about,’ I knew exactly what he meant. Somehow this mentally unbalanced, unloved, abused, ex-convict tough guy could state, with dignity and beauty in front of my camera, what I couldn’t say myself.

“Danny Lyon: Message to the Future,” is on view at the Whitney Museum in New York through September 25. Excerpts of his films can be found on Lyon’s website, BleakBeauty.com.