It’s been a beautiful summer, at least in the Northeast, but much about the current election cycle has made it something of a challenge to have any sort of fun at all. How doubly grateful we are, then, to find distraction, humor, entertainment, and pleasure in two museum shows devoted to so much funny, engaging, and ultimately moving evidence of our search for instructive or simply comforting messages from the beyond. The shows—“Imponderable” at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and “Tony Oursler: The Imponderable Archive” at the Hessel Museum at Bard College’s Center for Curatorial Studies—reveal the intriguing connections between the work of video artist Tony Oursler and his encyclopedic and obsessive collection of over 2,500 images and objects. Nearly all of these objects touch on some aspect of the occult or, perhaps more accurately, on beliefs and belief systems that cannot be supported by (or that run counter to) science. They provide evidence of the (often misguided) power of faith, and of our longing to believe in—or our compulsion to disprove—the existence of phenomena that we know to be unlikely, irrational, illogical, or physically impossible.

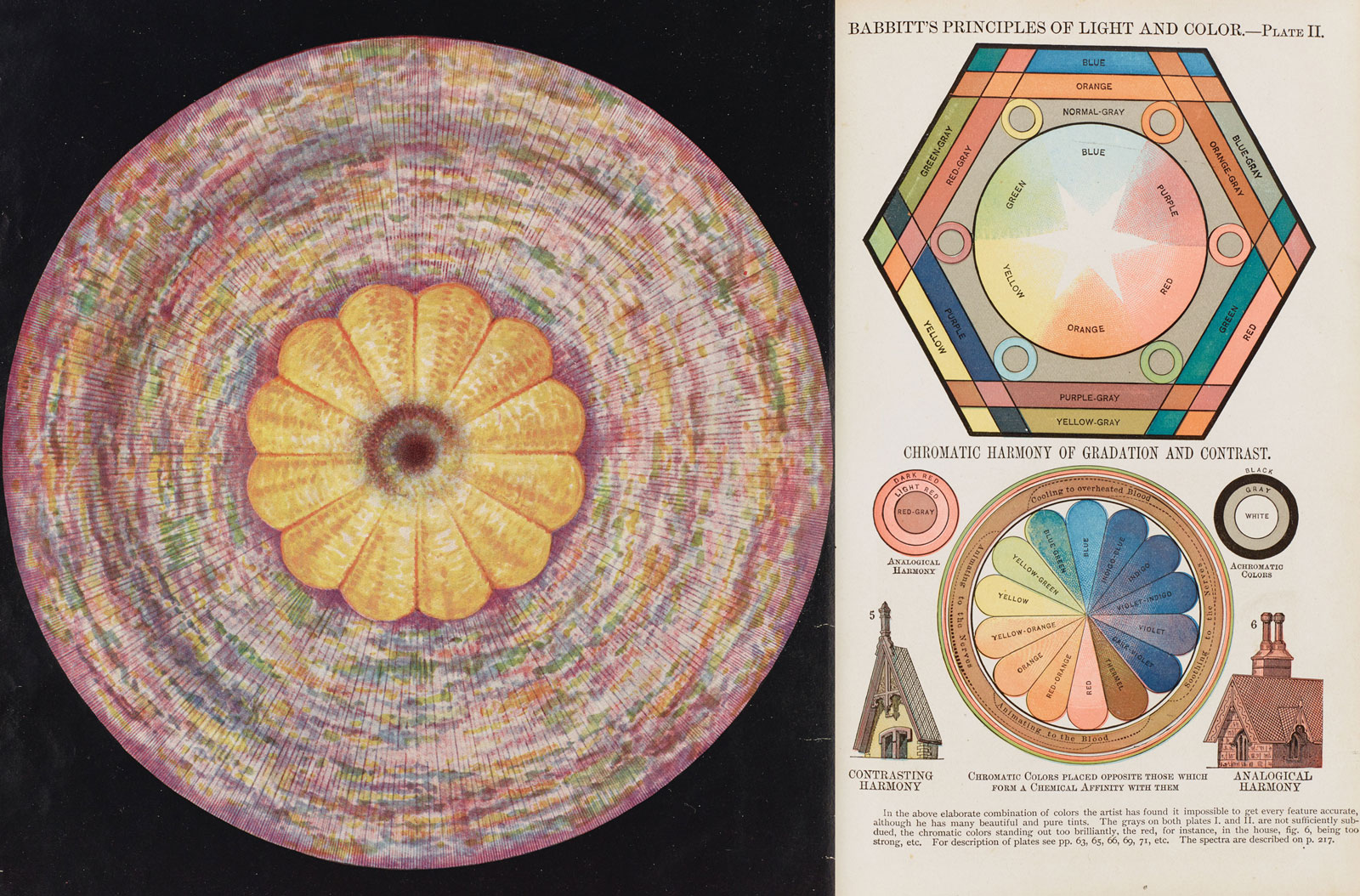

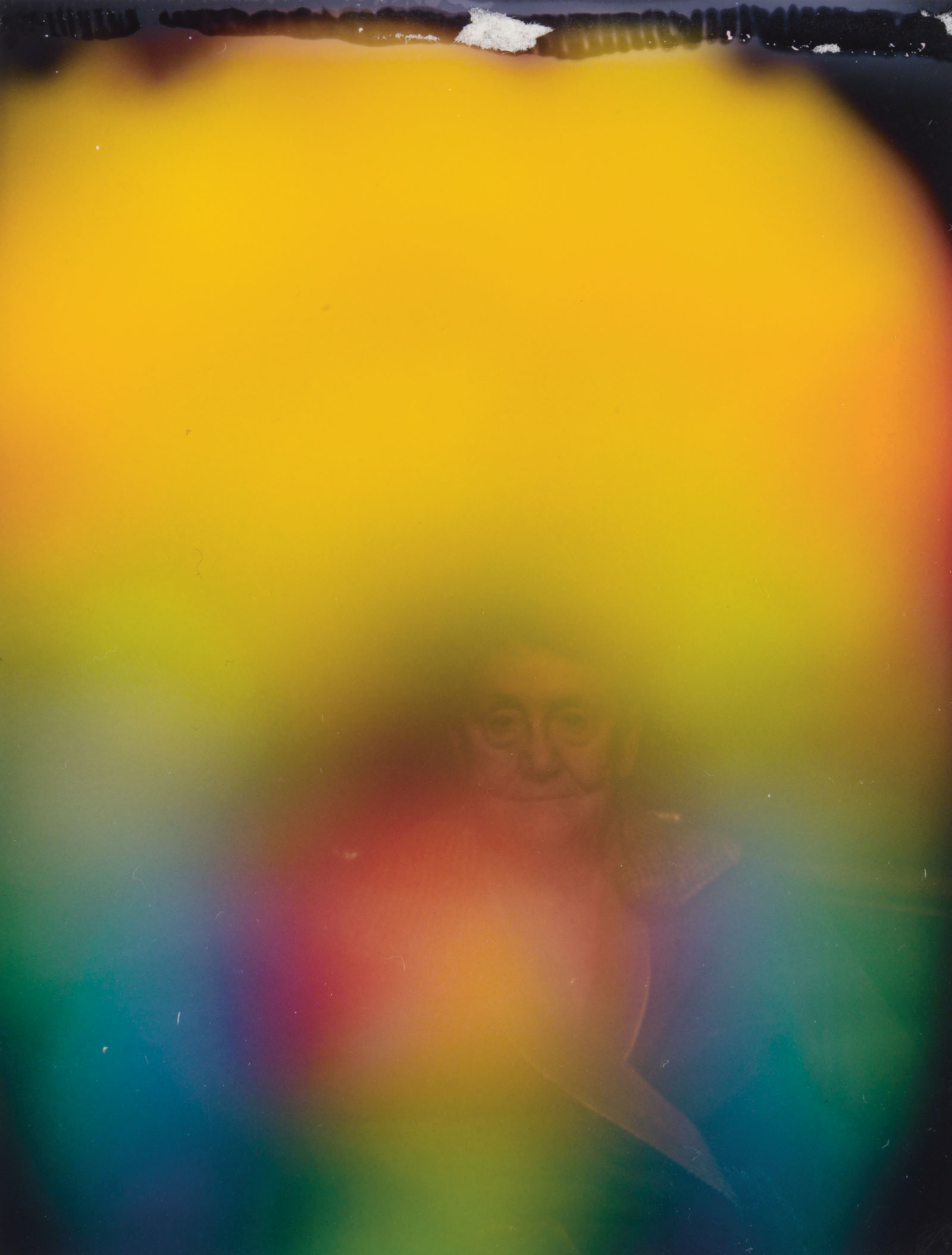

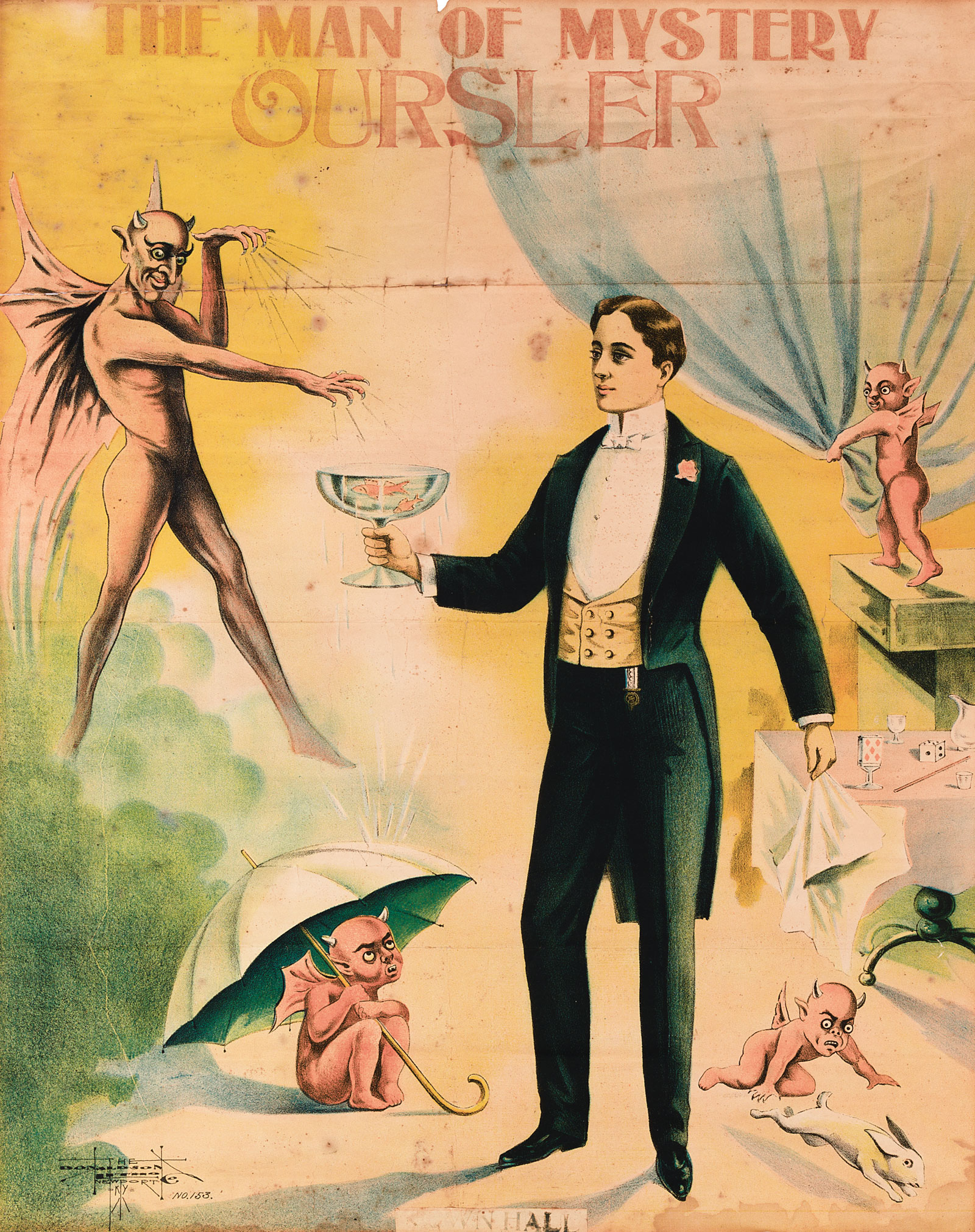

Born in New York in 1957, Oursler attended the California Institute for the Arts, where he met the artist Mike Kelley, another passionate collector. Oursler’s earlier works include a timeline of technologies (beginning with the camera obscura) “that may or may not be used in cultural production,” and installations and sculptures in which videos of expressive human faces are projected onto inanimate forms. The artifacts that Oursler has assembled over his career allude to the miraculous (the figure of the Virgin Mary imprinted on a rose petal), the paranormal (the outlines of Thomas Becket’s ghost visible on a pillar in Canterbury Cathedral), the criminal (newspaper photos of Charles Manson, Jonestown, and Patty Hearst), the quasi-scientific (a portable E-meter from the early days of Scientology; a print of a “Japanese mermaid” that resembles a hybrid of a dinosaur, a chicken, and a fish), and the simply strange (pictures of a psychic who conned trusting senior citizens by conjuring devil’s heads from tomatoes, and of Viennese cult members wearing pacifiers to signify their rejection of adult society). There are voodoo dolls, shrunken heads, tarot cards, reliquaries, shadow puppets, magic lantern slides, astrological charts, palmistry and phrenological diagrams, an antique color wheel, and a wide assortment of stage props and ritual objects. Everywhere are pictures of “natural wonders” (human faces and forms appearing on rocks, in the snow, in the spray from waves; angels sighted in the clouds; the head of Christ materializing in a grove of trees) and of feats performed by stage magicians, hypnotists, and mediums. Many of the film and theater posters, book jackets, and pamphlet covers are small masterpieces of campy but nonetheless striking graphic design, and there are some marvelous ephemera (a series of dream drawings done by Federico Fellini), movie stills (a portrait of Charlie Chaplin as the Great Dictator), and photos of sets from vintage detective and horror movies that testify to the ways in which film blurs the division between reality and illusion. We can easily intuit, but may find it hard to explain, exactly why these items so clearly belong together, especially since the ways in which they resemble one another are, in some cases, more visual than contextual. Thus images of political figures (Jimmy Carter, Senator Joseph McCarthy) being burned in effigy recall dazzlingly bright ghostly emanations, while some rather lovely Rorschach-test blots are not unlike the delicate water colors depicting the heads and faces of spirits. An illustration of “The Crown Chakra” done by the Rit. Rev. C. W. Leadbeater in 1927 vaguely recalls a page from The Principles of Light and Color, by nineteenth-century mesmerist Edwin D. Babbitt, who believed that “all ailments and diseases could be attributed to an imbalance in the individual’s ‘color field,’ or aura.”

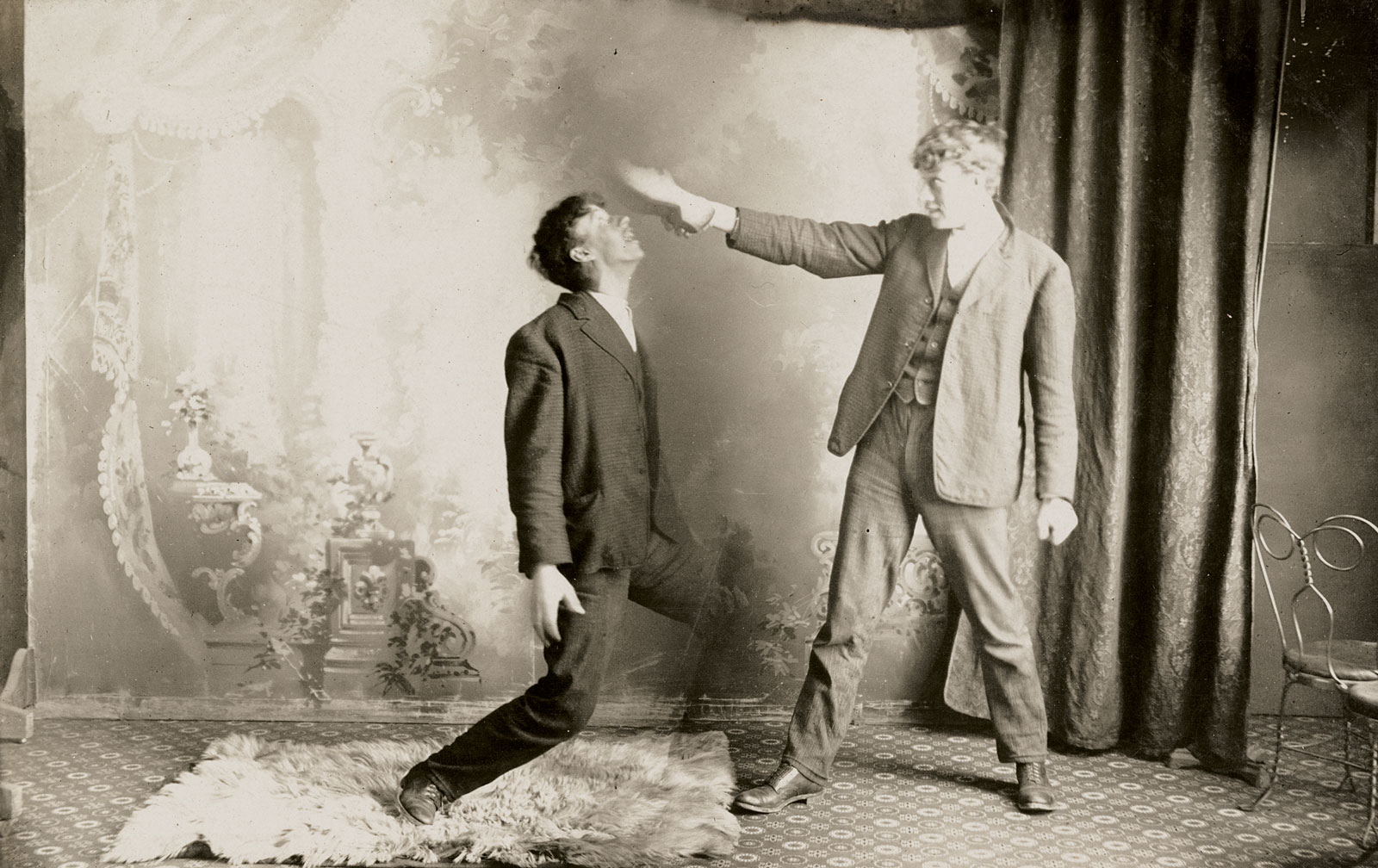

At the MoMA show, organized by Stuart Comer and Erica Papernik-Shimizu, a selection of these artifacts is on view in a gallery just outside the theater showing Imponderable, Oursler’s deadpan, zany, inventive new ninety-minute film. Outrageously costumed and heavily made up, declaiming their lines as stiffly and awkwardly as grade-school thespians, the film’s actors impersonate Harry Houdini, Arthur Conan Doyle, and various mediums, spiritualists, charlatans, specters, and devils, while flames and ethereal bodies (and body parts) cavort among them. The film’s subject, loosely speaking, is the effort of early-twentieth-century rationalists (among them the artist’s grandfather, Charles Fulton Oursler) to debunk Victorian fairy and spirit photographs, séances, and other manifestations of the belief that the dead can be contacted and that our lost loved ones walk among us. The irony is that Oursler employs highly sophisticated technology to produce special effects (including an ingenious approach to “5-D,” utilizing colored lights, the simulation of a breeze blowing, and rumblings emanating from the theater itself) that seem, in their way, fully as mysterious, wondrous, and otherworldly as the gauzy apparitions that haunted Victorian gardens, photo studios, darkened parlors, and gas-lit theaters.

Advertisement

At the Hessel Museum, one can watch two of Oursler’s funny and imaginative video installations, Le Volcan and My Saturnian Lovers(s). But here the artifacts—680 of them—are the stars of the show. Curated by Tom Eccles and Beatrix Ruf, the objects are grouped in thirty-five glass-topped tables that evoke the museums—or, more specifically, the cabinets of curiosity—of an earlier era. The lighting (noticeably lower than we may be accustomed to experiencing in museums) is fittingly atmospheric, and the thoughtful exhibition design perfectly complements the material being displayed. Museum guards pass out booklets identifying the numbered objects on view and providing explanations that are immensely helpful, given that many of the apparitions and complex images would be difficult to see even at closer range and in brighter light. Fortunately, an enormous, ambitious, and handsomely designed catalogue—originally published to accompany the 2015 LUMA Foundation exhibitions in Arles and Zurich, republished for the current shows—allows us to spend the considerable time required to study the images and read the brief, descriptive texts that at least partly satisfy, or further inspire, our curiosity. In case we’re wondering how early-twentieth-century mediums insured that ectoplasmic entities visited their séances, a mini-collection of mesh panels, veils, and gloves, soaked in a fluorescent substance to make them glow in the dark, provides a credible explanation. And how, without help, could we understand what we are seeing in the 1963 news photograph in which “Blonde hypnotist Pat Collins, left, who not only attracts the Hollywood crowd to the Interlude on the Sunset Strip but gets ‘em onstage in droves as well, hypnotizes one of the famous names of the film colony…The young actress [Tuesday Weld], uninhibited normally, was hypnotized into believing she was a stripper.”

Among the intelligent and illuminating texts included in the catalogue are essays on Mesmerism, on UFO photography, on American female mediums, and on the early history of the cinema and its relationship to magic. But perhaps the most interesting articles are those that document Oursler’s ancestry. His grandfather, Charles Fulton Oursler, was a stage magician, a successful Hollywood screenwriter, an editor and publisher of True Detective and True Romance magazines, and the author of the best-selling biography of Christ, The Greatest Story Ever Told. He was also deeply committed to the debunking of the “occult sciences,” of mediums, and of practitioners of spiritualism. Frequently working with Harry Houdini, he took on such figures as Arthur Conan Doyle (a believer in fairy photography) and one of the most celebrated mediums of the 1920s, Mina “Margery” Crandon. A transcribed conversation between Tony Oursler and Crandon’s great-granddaughter, Anna Thurlow, is also included in the catalogue. A passage from that conversation comes close to the heart of what Oursler is doing in his archive and his work, at once “debunking,” gently mocking, and enthusiastically celebrating the fantastic, the surreal, the colorful world of the imagination, and the persistence of the faithful who hold fast to their beliefs despite how effectively and convincingly they are disproved.

“When people ask me about Margery,” Thurlow tells Oursler, “they always say, ‘Was she for real or not?’ And I always thought that was sort of missing the whole point of what she was doing. That the question of ‘fraud or not?’ was just a false question, that it was really more about how she did it, and why she did it, not whether it was real or not…Looking at your work—the projections with their disembodied quality, sort of old and new—there’s a similar feeling that I get from her pictures. She’s in these freakish poses and sometimes they look like a crime photograph. But at the same time, they thought they were doing something so modern, and you have these wild gadgets that they used at the séances…It’s kind of this juxtaposition.”

Advertisement

Carrying on the family tradition, Tony Oursler’s father was the editor of a publication entitled Angels on Earth, a magazine that presented “true stories about God’s angels and humans who have played angelic roles in daily life.” And, quoted in the catalogue, Oursler himself gives us what is perhaps the clearest, simplest, and most useful explanation of his own stance toward what he collects and creates:

Looking at this material, people may get the idea that I’m a believer. I am curious. But I’m not a mystic. Much as I’d like to be a levitator and talk with aliens, I haven’t. My artwork is expressing my great appreciation for all this belief. The joys of making art are my form of belief.

“Tony Oursler: Imponderable” is at the Museum of Modern Art through April 16, 2017, and “Tony Oursler: The Imponderable Archive” is at the Hessel Museum at Bard College’s Center for Curatorial Studies through October 30. Imponderable: The Archives of Tony Oursler is published by JRP|Ringier and distributed by Artbook DAP.