Two months into my freshman year at the University of Pennsylvania in the mid-1990s, I took a trip to Howard University’s homecoming by myself so I could catch a glimpse of their marching band. Because my friend forgot to pick up tickets, in those pre-YouTube days, I had to settle for hearing how exhilarating their performance was, how perfectly they timed their choreography to their song choice, by word of mouth.

During my next three years of college, I developed an even deeper longing: to attend the Bayou Classic and watch Grambling University’s “World Famed” Tiger Marching Band battle Southern University’s Human Jukebox, as they do every year on the Friday after Thanksgiving, and then again on that Saturday during the football halftime show.

The roots of this performance stretch much further back, to the post-Civil War period when newly freed African Americans began to experiment with sounds, styles, and what it meant to be an American citizen. In New Orleans, in particular, the fine brass bands drew on a number of traditions, including veteran military bandsmen who fought for the Union Army, first-rate musicians whose only source of income in the Jim Crow era was touring with minstrel troupes and on vaudeville circuits throughout the South, and sons of French creoles who were trained at the French Opera Company. And as more and more colleges were established for African Americans in the segregated South, these schools would hire many of these same military bandsmen or troupe players and enable a new generation to learn from these music masters.

Over the next fifty years, historically black colleges had so perfected this musical fusion and their brass band training that “by the 1960s, the collective style of black college marching bands had firmly taken root as a distinctive performance tradition,” William Dukes Lewis wrote in Marching to the Beat of a Different Drum: Performance Traditions of Historically Black College and University Marching Bands. “That was unlike their predominately white college band counterparts.” Today the Bayou Classic is known for its spirit of synchronicity, virtuosity, and utterly spectacular display of black musical excellence. It has inspired several other “classics” at other historically black colleges and universities, and even the 2002 film Drumline.

But watching the Bayou Classic on television is not enough. The colors and sounds are muted. The body’s own natural rhythms always somehow seem out of step with the dancers, drummers, and brass band musicians that beckon the viewer join them. I suspect even the spectators in the stands miss something, those intimacies that make up the collective: the countless hours of rehearsals, the waiting backstage or on the street corner with a tuba strapped to your hip. The long march away from the stadium. Neither those who had made the trek to New Orleans nor those watching at home are privy to these ordinary, quiet moments that complete the extraordinary portrait of the band.

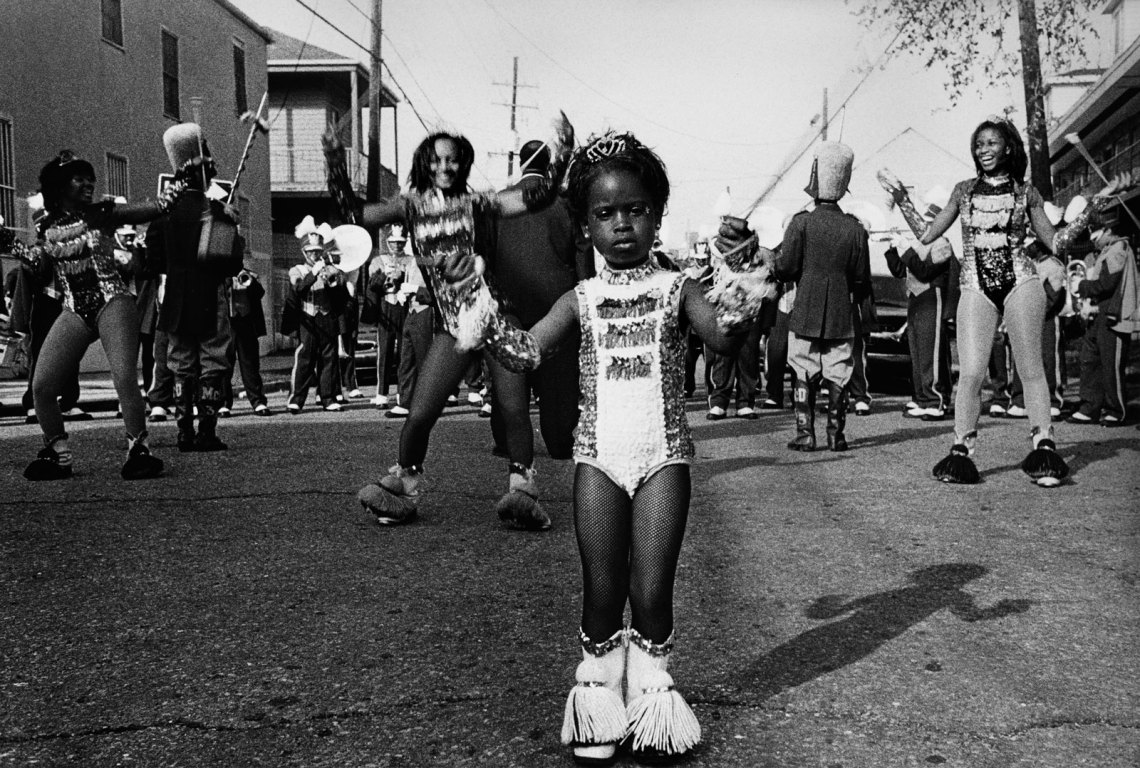

In Jules Allen’s Marching Bands, a stunning collection of social documentary, portraiture, and panoramic photography, he takes us into this behind-the-scenes world of African-American marching bands all over the country. “Whenever a marching band would come through, it would take me to pieces,” Allen has said. “In particular, Morgan State. They were just something else: the rhythm, the movement, the precision, the timing. What I call now the pulse and beat of what they were doing. It all seemed so particular to an African-American sensibility.”

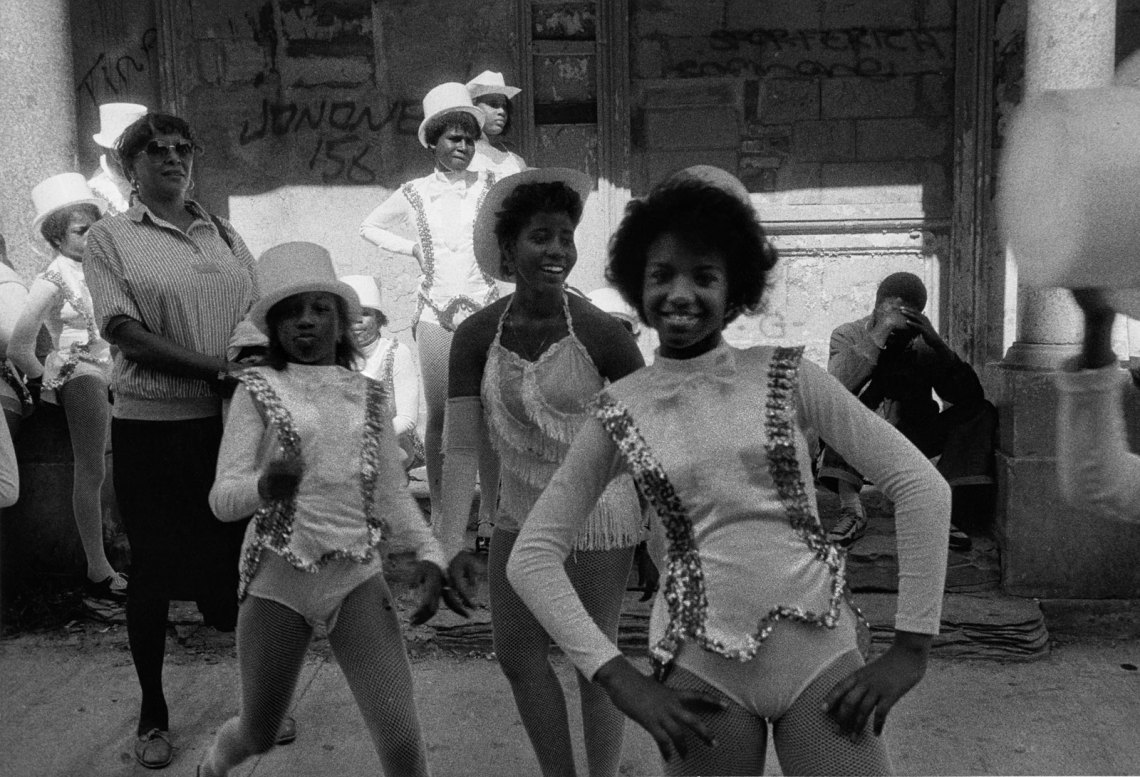

Allen, a photographer and a professor at Queensborough Community College, has previously captured the graceful grit of the boxer and the sacred pose of the nude. To Marching Bands, his fifth book, he brings that same attention to detail, the same focus on enveloping the viewer in the particulars of a world. Wisely, he does not limit us to the business of the spectacle itself, but rather blurs boundaries—between public and private, spectator and performer—seeming to make no distinction between a second line brass band parade in New Orleans, a Chicago drill team, and a Morgan State drum major in Baltimore.

By doing so, he shows how the community was built around these bands. In one of my favorite images, we spy a school marching band in downtown Durham, North Carolina. Flanked by a school bus and a parked car, everyone is in motion—they are either preparing for a parade or getting back on the bus. Drums are littered everywhere, even a trumpet on the ground, while one young man holds his arm up, trombone to his side, as if mentally rehearsing either his first notes or remembering his last ones. Behind him a young trombonist looks on, while to his right, a trumpeter in full costume stares. Band members walk in opposite directions, some smiling, some somber, as a mural, “The Black Wall Street Community,” creates a telling backdrop.

Advertisement

By pulling us closer to ways in which individual performances and styles help shape group expression, Allen shows us a black world that exists beyond and yet inside of the dominant culture. Through that lens, we can then appreciate the private thoughts behind the most public moments: a group of school girls peering out the side of a bus in anticipation, a band marching through the woods, a woman walking, with only a purse and raised umbrella in hand, after a second line parade in the French Quarter. On their own, each image marks a distinct moment in the performance; taken together, Allen gives us a history of black music and movement in the United States.

No Washington, D.C. area marching bands decided to perform at this year’s presidential inauguration. Among the forty historically black colleges and universities invited, only Alabama’s Talladega College Marching Tornadoes accepted, spawning a controversy among alumni and currents students and an online petition against their participation. The fallout not only suggests the centrality of the marching bands to contemporary American life, but how revered these institutions continue to be for African Americans. Allen’s book captures their grandness and communalism, their spiritedness and sacredness, and their power to be sites of political mobilization and cultural expressions in the days and years to come.

Marching Bands by Jules Allen is published by Queensborough Community College Art Gallery.