Although Black Mountain College, the legendary postwar incubator for the avant-garde, launched the careers of many twentieth-century luminaries who would eventually enjoy international renown, the sculptor Ruth Asawa (1926-2013) never quite became a household name—instead, her oeuvre has so habitually been relegated to the household. When the artist debuted her wire sculptures in New York in the Fifties, critics dismissed them as decorative or housewifely. “These are ‘domestic’ sculptures in a feminine handiwork mode,” wrote one critic in a 1956 ARTNews review. Because Asawa worked with common materials, twisting copper and iron into undulating forms, her art is often scoffingly associated with that art-world anathema: “craft.” And so a three-room exhibition of Asawa’s works at David Zwirner cannot help but feel restorative, an opportunity to reassess both the expansiveness and consistency of her vision.

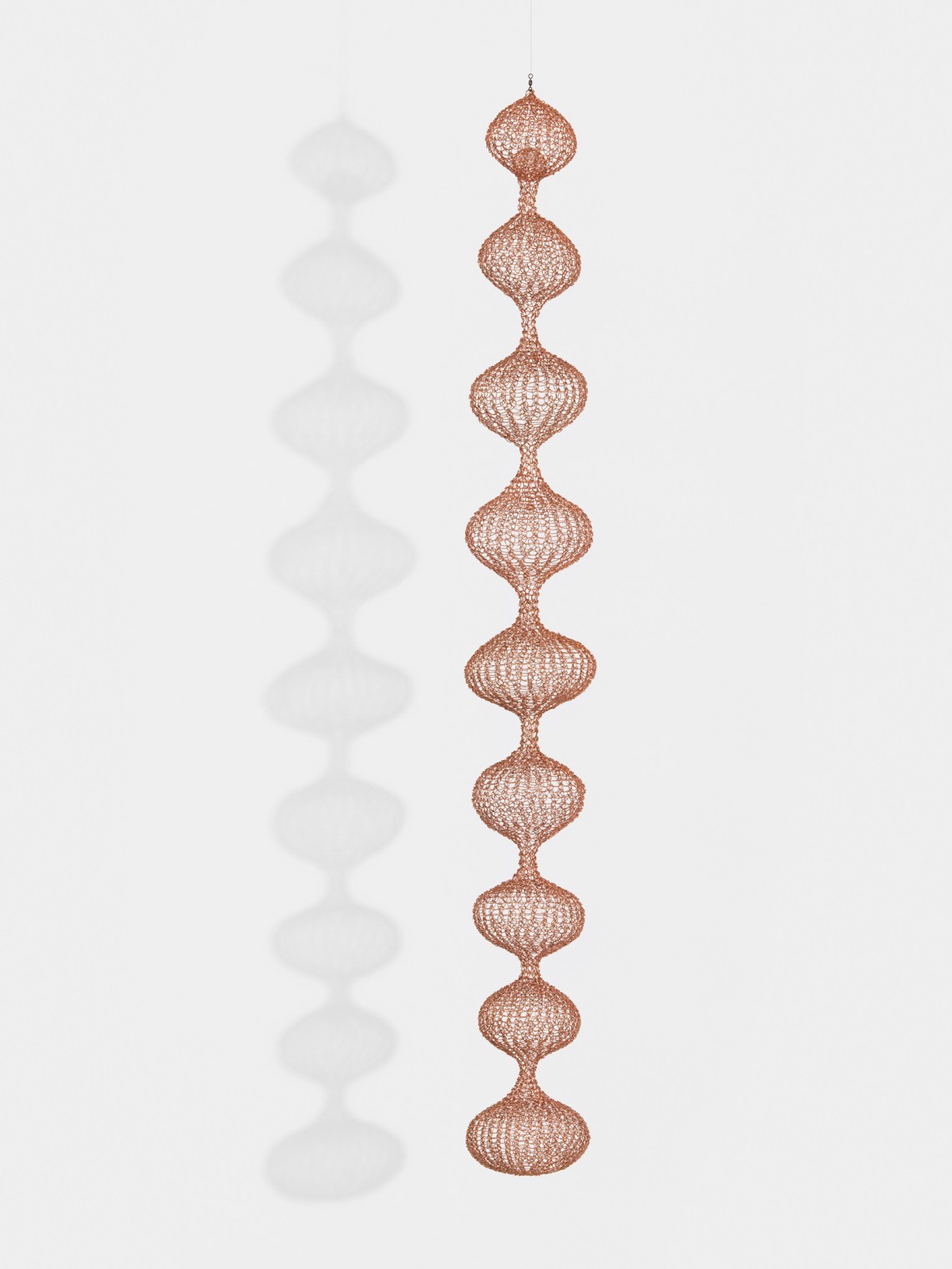

Asawa sought to evoke “transparent geometries” found in nature: the scales of a butterfly wing, a spiderweb, a wasp’s nest, or a reef of coral. Although most of what’s on display is from the mid-century, the show spans four decades. Its focus is rightfully placed on the suspended wire sculptures for which she is known. Made with a looping technique Asawa perfected after learning basketry in Mexico, the sculptures here are given the negative space they need.

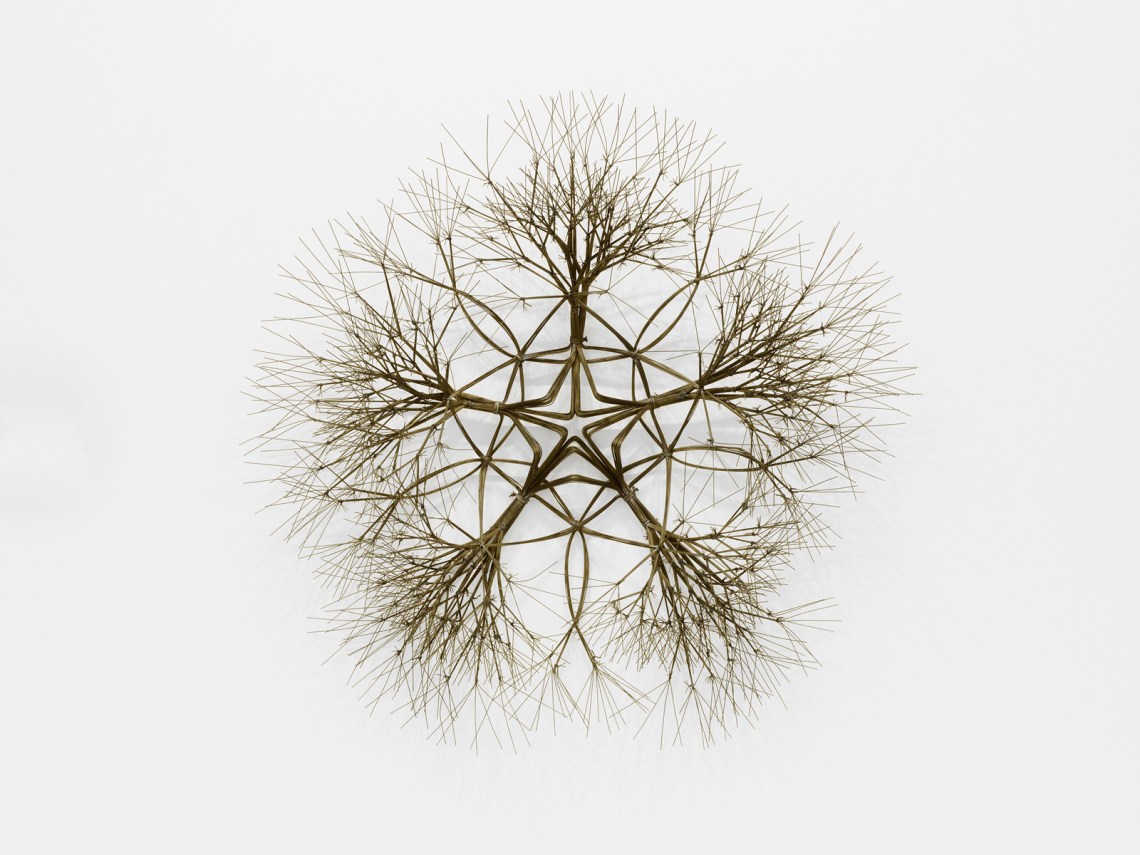

In the largest room, these works hang from the ceiling by wire and appear to levitate over a white, peanut-shaped stage. Included in the exhibition is a handwritten letter from Asawa to her husband, the architect Albert Lanier, in which she thought to mention that she enjoyed biology. “I laugh with the sun, and mist that tries so hard to seduce the mountains,” she wrote. Many sculptures bring to mind the chaotic symmetries and certainties found on an atomic level. Smaller mobiles also hang above the stage: orbs of various crocheted metals—brass, copper, gold-plated—that resemble homemade cosmogonies. Unlike other mobile sculptors like Alexander Calder and Joan Miró, Asawa is rarely considered a playful artist. There is an openness to wonder found in her attitude toward scale. This wonder radiates from two later works—wreaths of prickly brass and bronze festooned in different rooms—that are reminiscent of supernovae, of something from which life could begin.

Yet the universal implications of Asawa’s work are owed to the particularities of her struggle. After government agents tore Asawa’s father away from the family in 1942, the Asawas were relocated to a Japanese-American internment camp in Rohwer, Arkansas. In camps across the nation, detainees were often deprived of furniture, utensils, and blankets, and were forced to produce these items themselves despite the scarcity of materials. For many, craft became a prerequisite for survival. It was at Rohwer that a teenaged Asawa first learned to weave, making camouflage nets to be used in the war.

Asawa graduated from high school as an internee, but, because she was Japanese-American, she could only attend university if she left the West Coast military zone, and so she studied art at what is now the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. After being barred from a student-teaching program because of her ethnicity, she was prevented from earning a degree, and she then enrolled in Black Mountain College in North Carolina. There, under the tutelage of Bauhaus painter Josef Albers, she drew further inspiration from the elemental world. If the college—remembered now for its communal ethos and chronic insolvency—allowed Asawa to refine a style premised on economical forms and a more modern design, it also introduced her to other modes of expression. Among the many instructors she studied with was the experimental dancer Merce Cunningham, and it’s easy to see her own wire works as vaguely figurative, stilled dancers imbued with the possibility of movement.

Asawa’s drawings, along with colorful oil and ink works mostly made in the late Forties, reiterate the primacy of process over product found in her three-dimensional works. Asawa claimed that her sculptures were “drawings in space” and, indeed, one can consider the wefts of wire hung in the gallery to be intricate crosshatches, formed only by a couple of threads of warped metal. One undated pencil drawing looks like a galactic tumbleweed, while a selection of painted shapes offers a subdued whimsy absent in the sculptures.

Advertisement

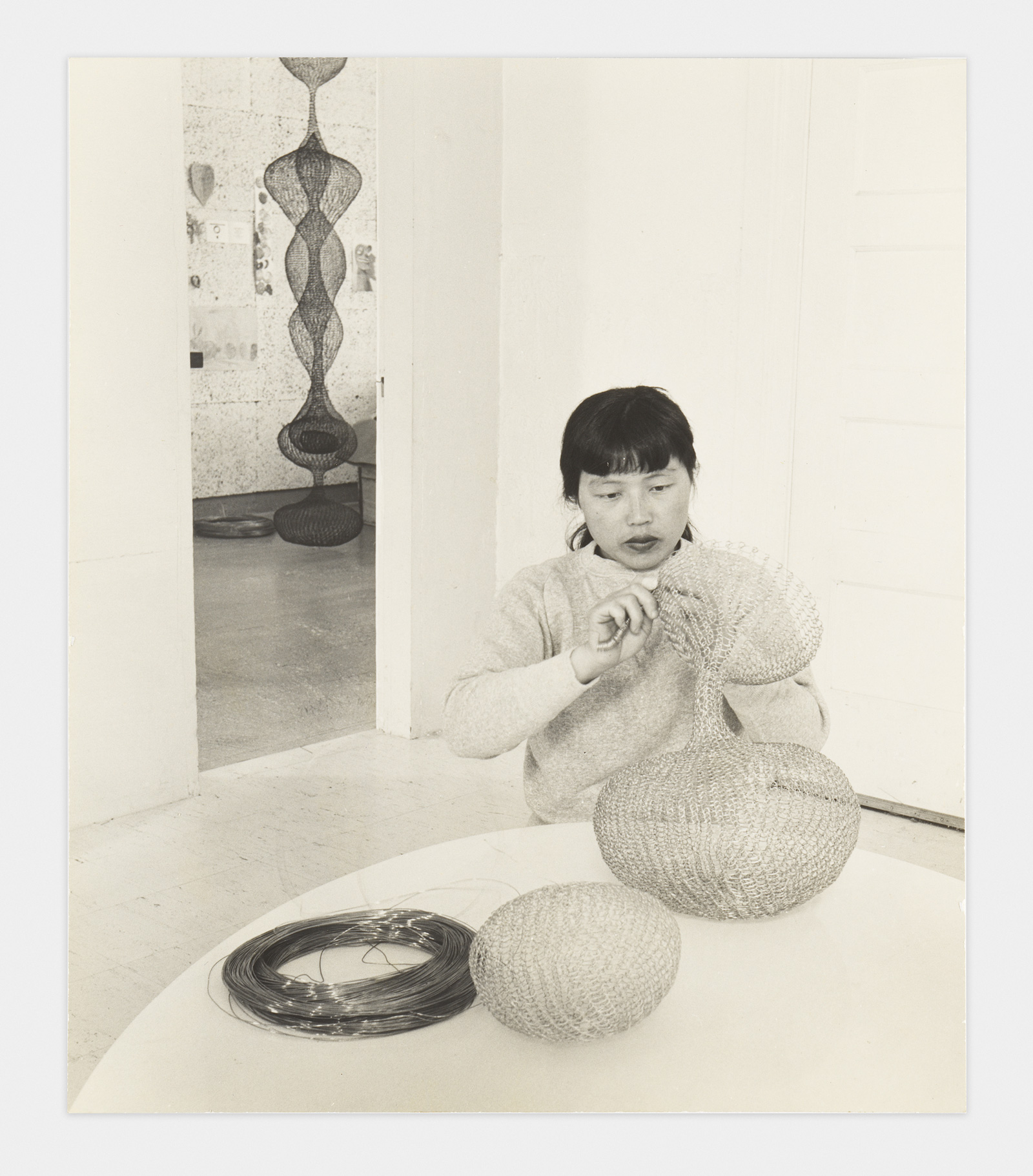

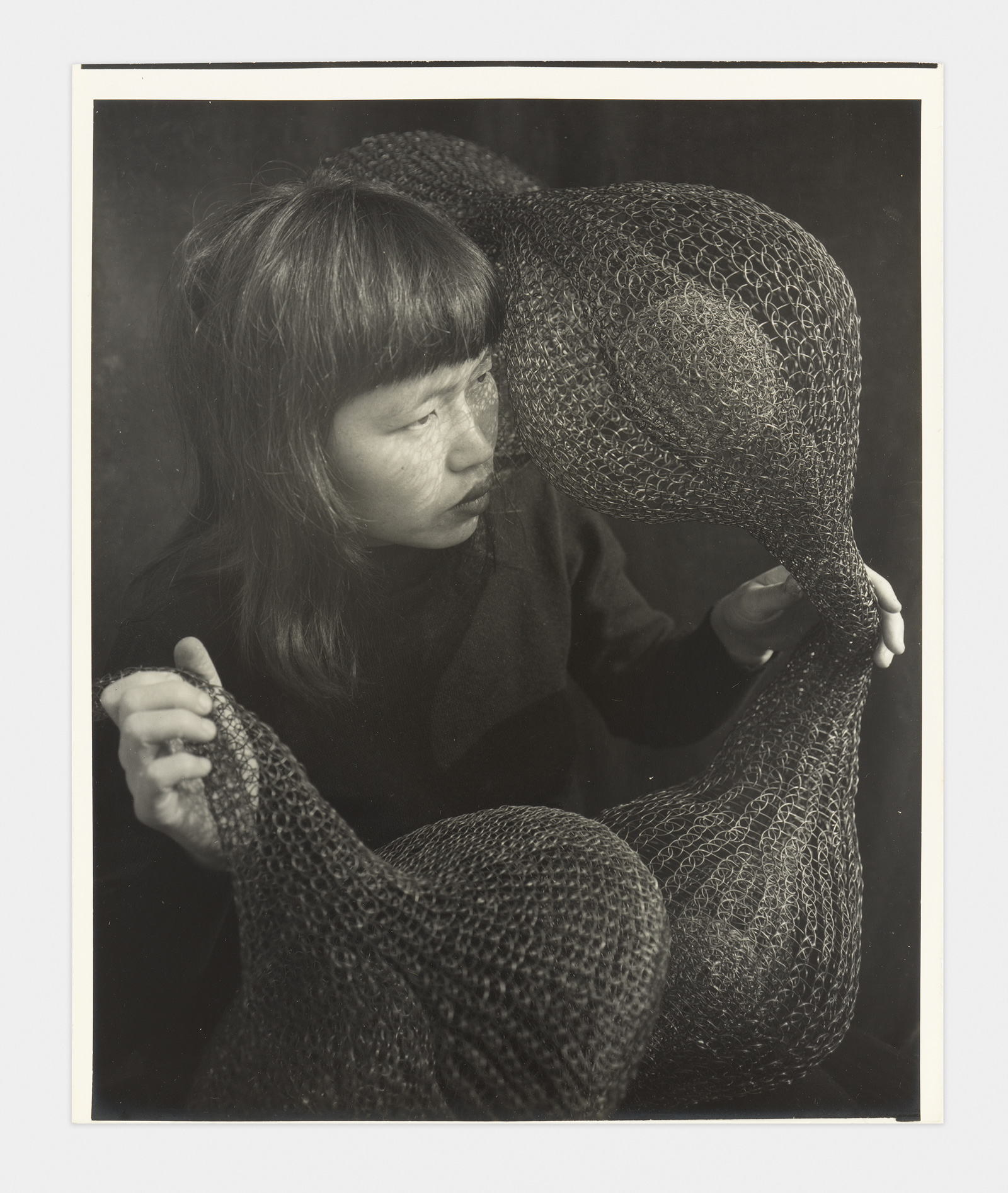

Elsewhere in the gallery, a vitrine showcases photographs of Asawa and her work taken by the photographer Imogen Cunningham, whom she met not long after moving to San Francisco in 1949, and who became a lifelong friend. Asawa’s art presented an ideal subject for the photographer; within these sculptures, the genres Cunningham is most known for advancing—botany and the nude—coalesce. In the pictures she took there never seems to be a moment free of making. Here Asawa crochets metal, cross-legged on the floor surrounded by her children. Here she adjusts a metal tree as others might tend to a garden. These photographs not only illuminate Asawa’s philosophy—the integration of creative labor with daily life—they are remarkable works of art themselves. In one 1952 portrait, Asawa wraps the gourds of a hanging sculpture around herself. The photograph is striking for its gauzy resilience, the way the woven wire reimagines medieval chainmail into something sinuous and vulnerable.

Although the gallery notes that she was a diligent activist, Asawa never identified as one. “Activism is wasteful,” she said in an oral history recorded in 2002. From an artist whose practice is devoted to material thrift, this assertion feels especially damning. Still, a deep social commitment largely defined her art-making and her life. Along with advocating for public art education, she adopted a form of protest that was, essentially, a protest of form. Her artistic project became an act of endurance, as inevitable as nature itself. Perhaps this is why almost everything displayed in the gallery is untitled. Unnamed, Asawa’s works seem to belong not to any institution or individual, but to the very world that inspired them.

“Ruth Asawa” is at David Zwirner Gallery through October 21.