This month, the United States Treasury Department quietly released a new set of regulations rolling back the rights of Americans to travel and do business in Cuba. The move is the latest and by far the most significant by the current administration to deliver on the commitment President Trump made in a speech in June to nullify “the last administration’s completely one-sided deal with Cuba.” Ostensibly pursued to stop the flow of money to the Cuban government until it grants greater freedom to the Cuban people, these new restrictions will have the opposite effect of strengthening the hand of hard-liners in the Cuban government.

On December 17, 2014, when President Obama announced that he was taking steps to normalize relations with the government of Cuba, I watched from the office of my boss at the time, the then-US ambassador to the United Nations, Samantha Power. The announcement had been kept under tight wraps; apart from the ambassador herself, it was news to the rest of us at the US mission to the UN. President Obama argued that while the US was as committed as ever to promoting democracy and human rights on the island, fifty years had made clear that the embargo was not the way to do it. Rather than curbing abuses, the embargo was giving the Castro government a scapegoat for its unfulfilled promises and a pretext for locking up its critics.

The steps Obama laid out that day included reopening the American embassy in Havana and lifting many of the restrictions on US investment and travel. This dramatic shift represented about as much as the executive branch could do to change the US’s Cuba policy, since the 1996 Helms Burton Act ensured that only Congress could end the embargo altogether. The initiative culminated in Obama’s historic visit to Havana in March 2016, when, with Raúl Castro looking on, he did what no sitting US president had done since the Cuban Revolution: make the case for greater freedoms directly to the Cuban people.

Before going to work in the Obama administration, I had covered Cuba as a researcher for Human Rights Watch, when I’d been able to speak to Cuban dissidents only over phone lines tapped by the Cuban government, or by unannounced visits to their homes (which were under near-constant surveillance). By 2015, I could openly receive some of those same dissidents in the offices of the US delegation to the United Nations.

Which is not to say repression on the island stopped. Dissidents continued to be harassed, beaten, and locked up. They still were fired from jobs and saw their kids expelled from school as punishment for the parents’ activism. And other countries continued to be reluctant to speak up about the Cuban government’s ongoing abuses. Every year for the last quarter-century, the UN General Assembly has voted on a resolution condemning the US embargo on Cuba. And every year, nearly all UN member states have voted for the resolution. (In 2015, only the US and Israel voted against it.) When, in October 2016, for the first time in history, Ambassador Power cast a US vote to abstain—rather than oppose—the resolution, the UN General Assembly erupted in applause, and countries from around the world praised the Obama administration for re-engaging with Cuba.

Despite such support, the UN vote also showed how hard it is to get other governments to say in public what they concede in private: that the embargo is far from Cuba’s only problem. At the same time as Ambassador Power acknowledged in her remarks that day that the embargo had done more to isolate the US than Cuba, she also made clear that the Cuban government was one of the greatest obstacles standing in the way of opportunities for its people, and called on other countries to say as much. Almost none did. Indeed, to hear other diplomats speak that day—and not just those from autocracies like Russia, Egypt, and Sudan, but also from democracies like India and South Africa—one would think Cuba was a progressive paragon of rights.

This speaks a deeper truth about the new policy pursued by the Obama administration. While greater US engagement removed one of the main impediments to Cuba’s moving toward greater openness and freedom, it could not by itself bring about that change.

Critics of Obama’s Cuba policy often pointed to this as proof of its failure, as though it were reasonable to expect that re-engagement would instantly produce a democratic transformation in Cuba. Never mind that many of those critics seemed happy to stick with an embargo policy that had failed to produce meaningful progress for more than half a century. What they misunderstood is that engagement was never an end in itself, but a means to build the pressure necessary to put Cuba on a different path. By that measure, Obama’s policy succeeded, as it led to the Cuban government’s decades-old excuse finding fewer sympathetic ears—both on and off the island. It also allowed the US to engage more effectively in other important diplomatic efforts in the region, such as the Colombian peace talks then being held in Havana.

Advertisement

That progress is now in jeopardy. On June 16, 2017, before an audience packed with Cuban Americans in Miami’s Little Havana (who repeatedly interrupted his speech with chants of “USA! USA!”), President Trump said that the Obama administration, “made a deal with the [Cuban] government that spreads violence and instability in the region, and nothing they got—think of it—nothing they got.” Trump said that the steps taken towards normalization had only enriched the Cuban government and had led to more repression on the island. “Effective immediately,” he announced, “I am canceling the last administration’s completely one-sided deal with Cuba.”

Yet, for several months after that, Trump left important elements of the Obama administration’s Cuba policy in place. The US embassy in Havana and its Cuban counterpart in Washington remained open, and cooperation between the countries on issues of mutual interest, such as counterterrorism and disaster response, continued. That began to change when, in August and September, more than twenty employees of the US embassy in Havana reported a series of mysterious illnesses believed to have been caused by sonic attacks. While FBI investigators (whom the Cuban government allowed to visit Havana) have not as yet been able to determine who was responsible, the Trump administration responded by withdrawing diplomatic staff from the embassy, warning US citizens not to travel to Cuba, and expelling fifteen diplomats from the Cuban embassy in Washington.

The Trump administration has said these actions were aimed at protecting US diplomats, but two moves in recent weeks suggest that Trump may be set on unraveling US-Cuba engagement altogether. The first came on November 1, when the UN held its annual vote on the resolution condemning the Cuba embargo and the Trump administration returned the US to voting against the embargo, reversing Ambassador Power’s 2016 abstention. The second came a week to the day after the UN vote, on November 8, when the Treasury Department reverted to the old restrictions on Americans’ right to travel to, and do business in, Cuba. The new regulations will have a swift and significant impact. From January to May of 2017, some 300,000 Americans traveled to Cuba, more than visited in all of 2016. Now Americans who want to visit Cuba will again be limited to tours sanctioned by the US government, permission for which the Trump administration can make as stringent as it wants. Numbers will drop precipitously.

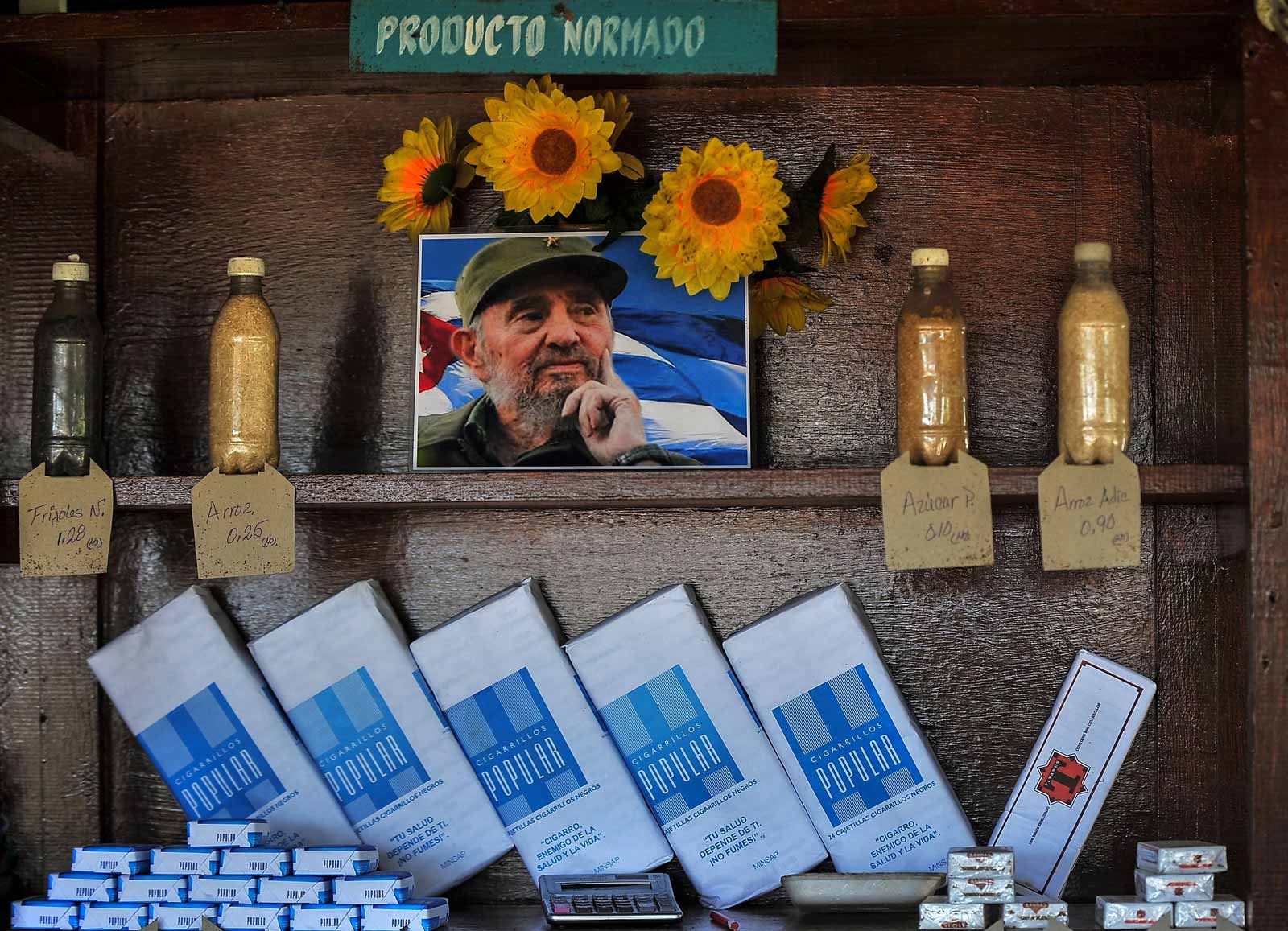

The regulations will also make it tougher for Americans to do business in Cuba. US companies and individuals will be barred from engaging in any economic activity with entities tied to the Cuban military, security, or intelligence services, because, as Trump said in Miami, “We do not want US dollars to prop up a military monopoly that exploits and abuses the citizens of Cuba.”

Trump is right: the Cuban military does exploit and abuse its people. The problem is that Cuba is governed by a military regime, which has a hand in virtually every aspect of the country’s economy, from hotels to farms to rental car companies. Cuba’s private sector, while entrepreneurial and growing, is minuscule by comparison. So not engaging with the Cuban military means barely doing business at all. But as the last fifty years have demonstrated, a US embargo will not starve the Cuban military into submission. Embargoes, like all sanctions, work only if other countries are willing to enforce them (see: Iran), and the rest of the world has no qualms doing business in Cuba.

The reversion to making any changes to the embargo conditional on the Cuban government’s respect for human rights will obstruct the very shift that Trump says he seeks in Cuba, in no small part because it will make it much harder for allies to work with the US on the issue. It will also be an obstacle to addressing other crises in the region on which US leadership is crucial, like Venezuela, where patients are dying the hallways of hospitals that have run out of basic medicines, and the government has cracked down violently on mass protests, tortured its opponents, and systematically dismantled independent checks on its power.

The US disengagement could not come at a less opportune time. Raúl Castro has pledged to retire from his position as president and head of the armed forces in 2018, marking the first time in nearly six decades that the Cuban government will not have a Castro at its helm—a transition sure to have profound implications for the island’s future.

Advertisement

And what’s the reason for the disengagement? Surely not the US administration’s sincere commitment to human rights, as Trump’s embrace of leaders like Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte, and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan demonstrates. On the day the new Cuba regulations were announced, President Trump was in China, where he made no mention of human rights or any desire to promote democracy and fundamental freedoms.

Trump’s Miami speech was, of course, intended to appeal to Cuban Americans—a key constituency in the swing state of Florida, which carries twenty-nine electoral votes. But even as a cynical electoral strategy, the reversal of the Obama administration’s diplomatic opening with Cuba is misguided. In the 1990s, on average, 84 percent of Cuban Americans in Miami supported the embargo. Today, only 37 percent do. Opposition to the embargo is even more pronounced among Cuban-American youth—a population that, like the rest of America, supports greater engagement with Cuba.

But there may be a silver lining. President Obama used his executive authority on Cuba policy because Congress, the only body that has the power to lift the embargo, could never muster the votes to do so. Yet support for lifting the embargo is growing, bringing together an alliance of unlikely bedfellows, all strongly critical of Trump’s reversal on Cuba policy (albeit for very different reasons): from rural farmers and ranchers represented by groups like the American Farm Bureau Federation, to conservative think tanks like the Cato Institute, to progressive faith groups such as US Conference of Catholic Bishops, to rights groups like Human Rights Watch, to business associations like the US Chamber of Commerce.

Increasingly, too, Democrats and Republicans from across the ideological spectrum are lining up together on the issue. A few weeks before Trump’s Miami speech, Senators Jeff Flake (Republican of Arizona) and Patrick Leahy (Democrat of Vermont) reintroduced a bill that would eliminate all restrictions on travel to Cuba by Americans. When it was originally proposed in 2015, the legislation had eight co-sponsors in the Senate. Now it has fifty-five, at a time when marshaling cooperation across the aisle on any issue is almost unheard of. And that was before the Trump administration announced its latest round of restrictions.

By galvanizing a coalition to lift the embargo altogether, Trump may turn out to be the one who fixes the US’s broken Cuba policy after all. Just not in the way he intended.

Yet that possibility is slim, at best. More likely is a return to a status quo favored by the minority of hard-liners in both the US and Cuba, which will each go back to blaming the other for the lack of change. As usual, the ones who stand to lose the most are those whose interests both sides claim to represent, the Cuban people. They will continue to be hurt both by the embargo and by a government that uses them as a fig leaf for quashing rights.