It appears to be an artist’s work station, but with a naturalist’s focus: pencils, markers, and paints are positioned across the desk; a row of books includes such titles as Animal Invaders, Fire Ants, and Snakehead, while watercolors pinned to two corkboards feature delicate renderings of invasive pests. A map hanging between them tracks these different species with colored pins.

There’s a chair pulled up to the desk, with a green sweater draped over it. The scene looks if not interrupted then paused—a set of paints is open, a pencil and paper are laid out awaiting use. The artist must have just stepped out for a lunch break or a smoke. And yet, the sweater is a bit old-fashioned, and the fan on the desk looks vintage. A manual pencil sharpener peeks out from behind a bottle of vitamin pills. What year is it? How long has the artist been working here? How long has he been gone?

With this installation, Harbingers of the Fifth Season (2014)—now on view in “Misadventures of a 21st-Century Naturalist,” Mark Dion’s first US survey at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston—Dion has created a state of almost uncanny suspension: between past, present, and future; between naturalist and artist; between “artifice and authenticity,” to borrow the words of the critic Alastair Gordon describing in the catalogue “the realm that Dion chooses to inhabit.” This portrait of an absent artist who documents invasive species—perhaps a self-portrait—is remarkable not just for the depth of detail embedded in its seemingly simple surface, but for the way it encapsulates Dion’s own career.

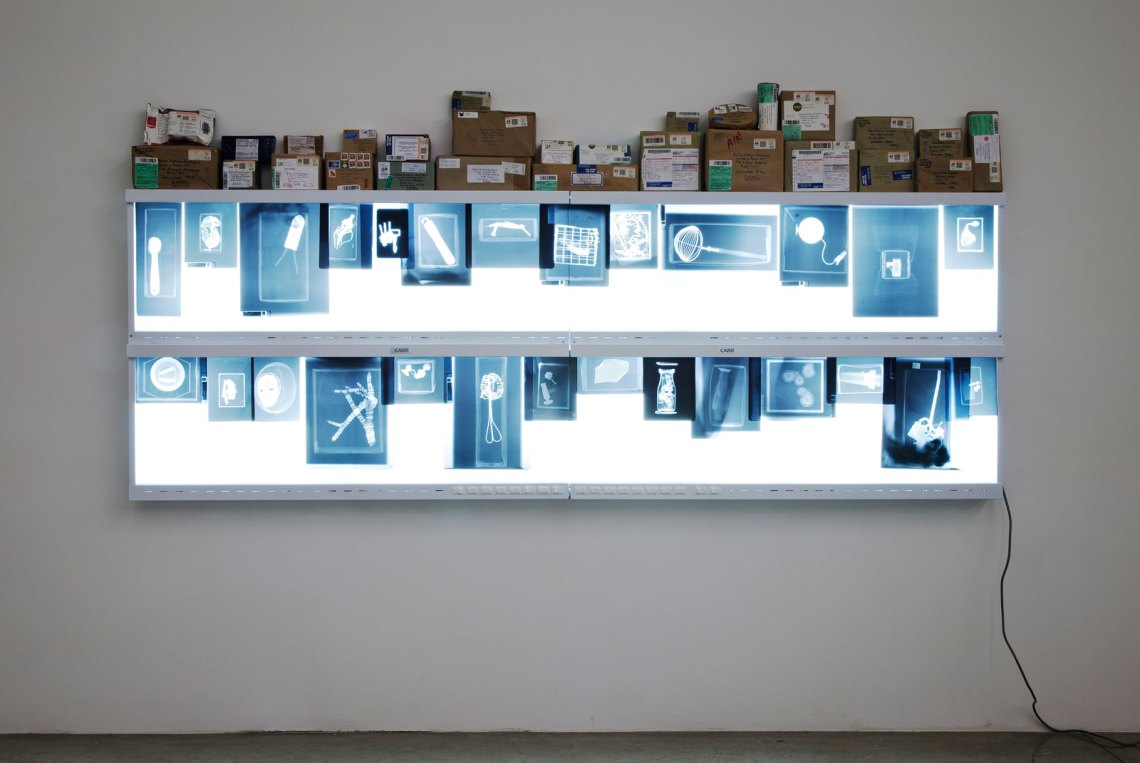

“Misadventures of a 21st-Century Naturalist” isn’t comprehensive, but it offers a good overview of Dion’s art. Viewers get an introduction to his primary method: gathering objects—whether on a DIY excavation or through the more casual means of collecting—and arranging them according to varying logics to create meticulous tableaux, often in the form of cabinets. The objects may be everyday items, like books, seashells, and nature-themed tchotchkes, or scientific specimens, like taxidermized animals; many installations place the two side by side. At the heart of this practice is a challenging but fruitful contradiction: Dion is a dedicated artist and environmentalist who repurposes older methods of museological and scientific inquiry, which are mired in colonialism and anthropocentric belief systems, in an effort to expose them.

To create On Tropical Nature (1991), for example, Dion camped for three weeks in the Venezuelan rainforest, where he collected specimens such as insects, feathers, bark, and soil; each week, he’d send his findings to a Caracas nonprofit art space called Sala Mendoza, where staff would arrange and display them on tables. The following year, in his second solo show at the gallery American Fine Arts, Co., Dion took some of those rainforest specimens and attempted to identify and preserve them under the aegis of the fictional NY State Bureau of Tropical Conservation. He had no formal training in such scientific processes, “eschewing the mantle of the expert” for “the openness and curiosity of the amateur,” writes Ruth Erickson, the lead curator of the ICA Boston show, in its catalogue. Both artworks, then, remind viewers that the methods of science—and the arts, for that matter—aren’t natural; they have always been shaped by the choices of humans.

This is the message that sounds the loudest throughout the exhibition, and it is stated explicitly in Dion’s insightful “Some Notes Toward a Manifesto for Artists Working With or About the Living World,” reproduced in the catalogue:

Just as humanity cannot be separated from nature, so our conception of nature cannot be said to stand outside of culture and society. We construct and are constructed by nature.

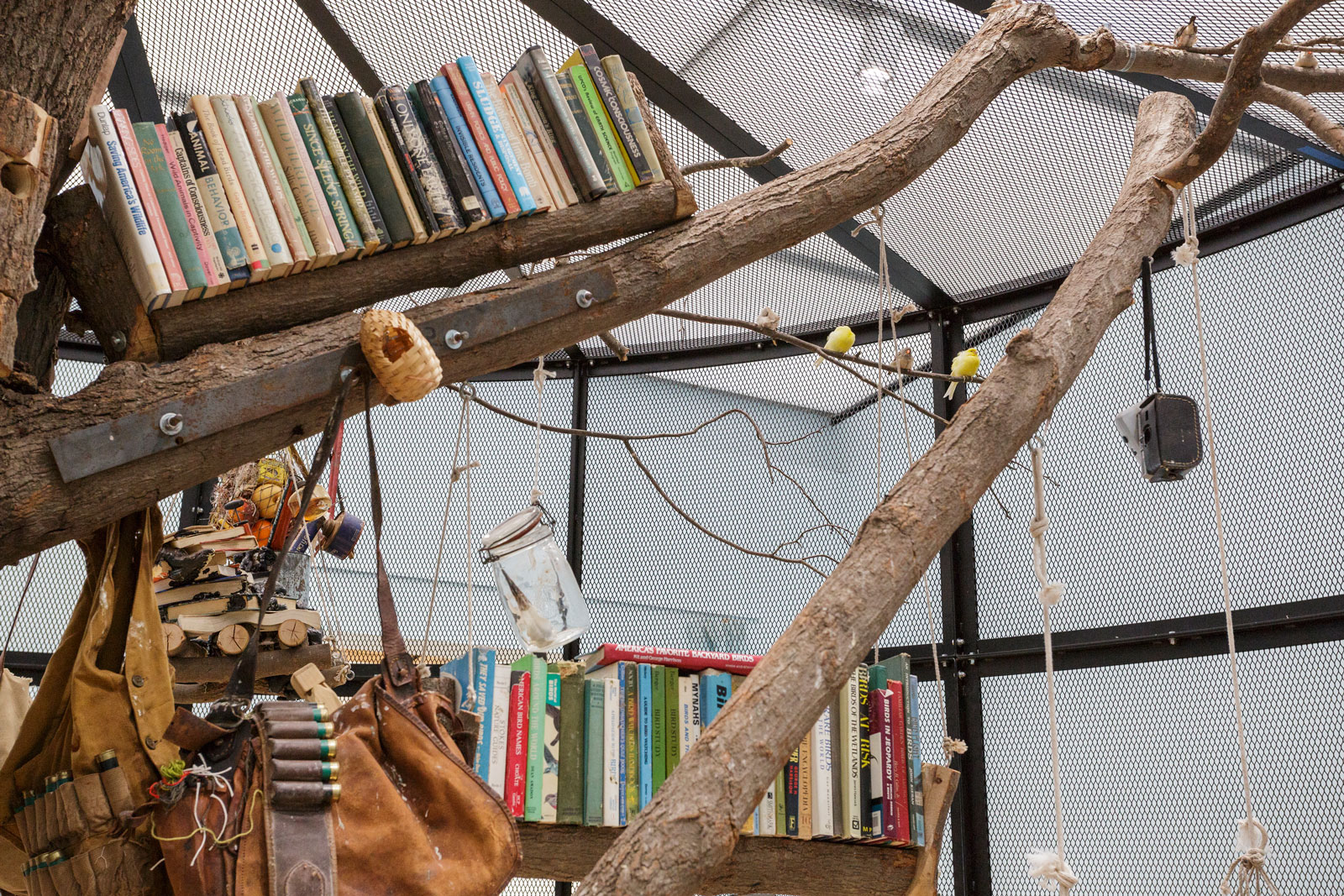

Dion is acutely attuned to this process of construction, and his best works make the viewer aware of it, too—whether they take the form of a fictional kid’s bedroom that’s been rocked by a dinosaur-themed cultural explosion (Toys ’R’ U.S. [When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth], 1994); a series of black-and-white photographs of polar bear displays in various museums (Ursus Maritimus, 1994); or a walk-in, oversize steel cage that houses books about birds and birding accoutrements alongside actual birds (The Library for the Birds of New York/The Library for the Birds of Massachusetts, 2016–2017).

Advertisement

Dion’s interest in the relationship between humans and the natural world extends to climate change, of course, which he represents in a number of powerful works. Landfill (1999–2000) transforms the standard natural-history museum animal diorama into a stunning display of environmental destruction, as gulls and a wolf range over a pile of human-made waste that’s filled with food packaging. Cabinet of Marine Debris (2014) similarly warps a scientific display trope: the curiosities so artfully arranged in this cabinet are colorful pieces of pollutant plastic that Dion gathered from the Pacific Ocean.

Dion is as devoted to form as he is to content, which saves him from veering into didacticism. In fact, at times he seems overly wedded to artifice: a few works in the show, including a series of faux nineteenth-century studio portraits of imaginary female natural-history enthusiasts, feel clever but ultimately distracting—why not seek out the histories of real, forgotten women instead? Still, Dion’s insistence on the possibilities of fiction as a means of illuminating truth sets him apart from many other environmental artists. Dion wagers that building a life-size diorama might help us humans to see our actions in a different way—to gain the perspective necessary to connect the dots between what came before us, what’s happening now, and what the future could be. In doing so, he opens up a space of imagination, where irreparable harm has already been done, but healing might also be possible.

“Mark Dion: Misadventures of a 21st-Century Naturalist” is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, through December 31.