From October 8 to December 3, 2017, Room Six in John Russell Pope’s West Wing at the National Gallery of Art played host to fourteen of Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s “fantasy portraits,” and for those eight weeks, it was transformed into one of the most beautiful galleries in the world. These celebrated half-lengths (and one three-quarter-length), done in 1769 (and perhaps the following years), are among the most inspired paintings produced in eighteenth-century Europe. Expressive and virtuosic in their handling, and said to have each one been painted “in an hour’s time,” they offer an affectionate collective of handsome men and women portrayed in the act of writing, composing, performing, or merely posing. All but one are shown in historical dress, referred to at the time as “Spanish costume,” which did not resemble contemporary Spanish apparel in any way. The beautifully produced catalogue leaves a permanent record of the bonhomie and exuberance of these dynamic canvases, last brought together in even greater number just under thirty years ago at the great Fragonard retrospective held at the Grand Palais in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The Washington, D.C., exhibition and catalogue celebrate the thirty-seven-year-old Fragonard as a practitioner of “pure painting”—an action painter avant la lettre. His rainbow palette is “parrot colored”—to use a term that was applied to Renoir in the heyday of Impressionism—and consists primarily of lemon yellows, creamy whites, scarlets, saffrons, and duck-egg blues. Fragonard presents his amiable and dashing cast of characters as if they had stepped out of a masquerade set in the reign of Henri IV. His men are wigless and gloved; they carry swords; and some wear chains of honor. The women sport Medici collars and lightly powdered, bejeweled coiffures. Each figure is posed behind a stone parapet and against an indeterminate background of scumbled browns and grays, illuminated from above. Painted as if au premier coup (in one go), Fragonard’s congenial sitters are caught mid-stream in a range of pleasurable, intimate activities. The spontaneity and speed of his performance are palpable: hues are blended wet on wet; brush strokes retain their traces; the tip of his brush inscribes zig-zag scribbles deep into the impasto of ruffs, collerettes, and sleeves.

While the term “fantasy portrait,” coined by Georges Wildenstein in 1960, is a useful shorthand, it is in some ways an unfortunate one. In Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, Voltaire had defined the portrait de fantaisie as a portrait that is “not made after an actual model”—something decidedly not the case here. Since their reappearance in the mid-nineteenth century, Fragonard’s canvases have formed a corpus in search of its identity. Like many of the protagonists of Watteau’s fêtes galantes, painted half a century earlier, Fragonard’s youthful figures—the majority in their late thirties or forties—appear in the costumes and accoutrements of a bygone era. The sartorial coherence of the series raises the possibility that Fragonard, again like Watteau, may have kept a box of costumes and props in his studio to be used by his models and, in this instance, by his sitters.

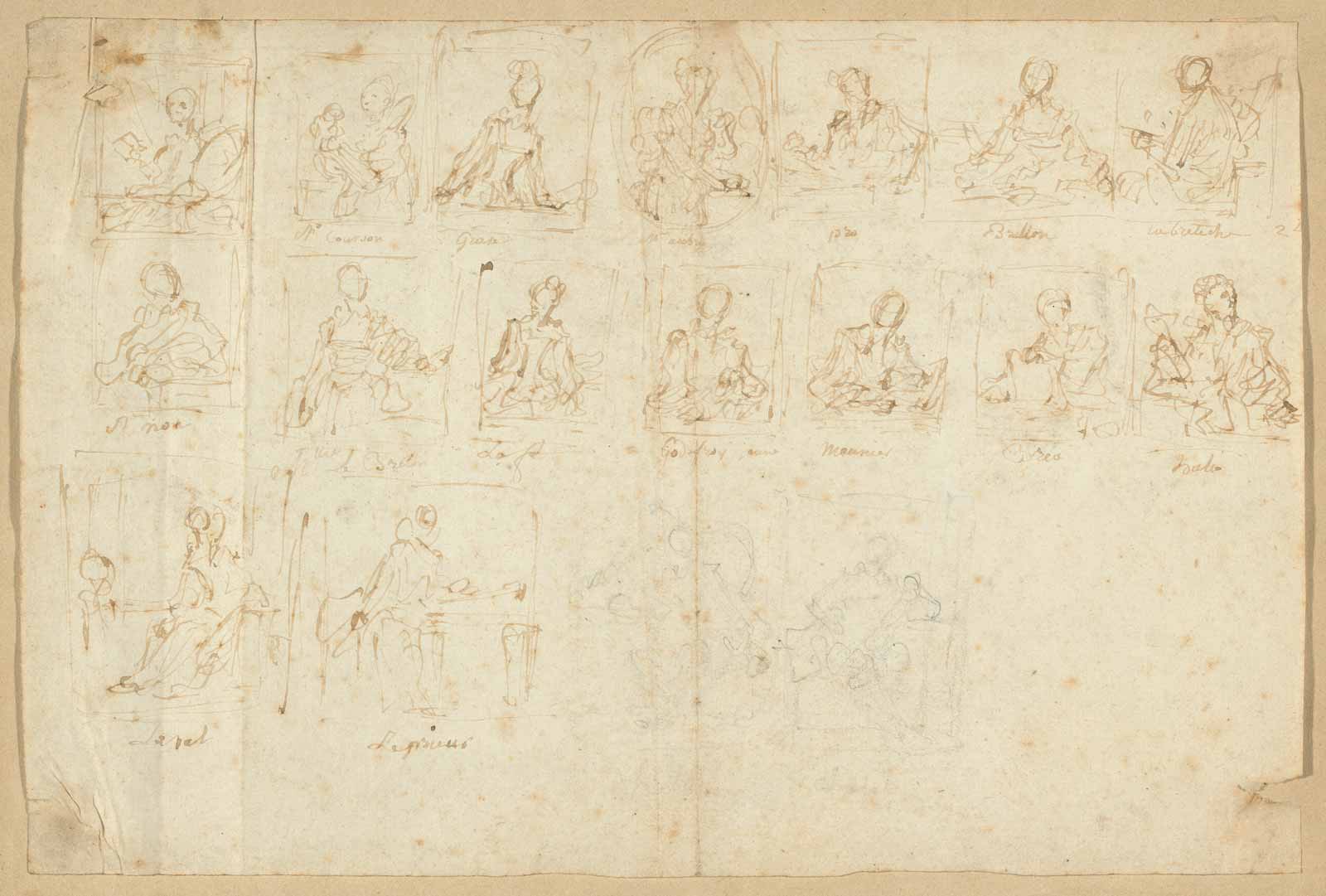

In the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Fragonard’s fourteen oil paintings were accompanied by a somewhat nondescript drawing by him, containing eighteen thumbnail sketches. This sheet had been completely unknown until it appeared at auction in Paris in June 2012, where it caused a minor sensation. These rapid sketches are Fragonard’s record of eighteen of his “fantasy portraits”—fifteen of which can be located today—with the names of his sitters hastily scribbled in casual, phonetic spelling. Not all of the known fantasy portraits are illustrated on this sheet (four of the core group do not appear) and, somewhat unexpectedly, the central sketch on the top row shows a vestal draped in white and identified as a certain “madame Aubry”: an oval canvas by Fragonard that until this time had never been associated with the series. In his haste to copy the group of canvases, perhaps, Fragonard may have run out of ink: his last two sketches, barely legible today, were done in graphite.

Fragonard’s annotations confirmed the traditional identities of only two of the fantasy portraits: the art-loving cleric and patron, Jean-Claude Richard, abbé de Saint-Non, and his brother, Louis Richard de La Bretèche. The remaining fifteen annotations revealed new, and more obscure, identities for the sitters, including two of the most celebrated portraits. The painting in the Louvre long thought to have been of the courtesan and dancer Marie-Madeleine Guimard is now identified as the comtesse Marie-Anne Éléanore de Grave, from venerable Burgundian aristocracy, whose youngest son would become Louis XVI’s last minister of war. Far more sensational, and reported in both Le Monde and Le Figaro, Fragonard’s canonical Portrait of Diderot no longer represents the esteemed philosophe, but instead a minor and forgotten author, pornographer, and publisher, Ange-Gabriel Meusnier de Queron: at sixty-seven, the oldest sitter in Fragonard’s gallery of worthies.

Advertisement

The primary revelation of Fragonard’s summary and—at times, barely decipherable—annotations is to introduce a socially variegated and unfamiliar world of patrons, clients, and (perhaps) friends into his orbit, from the high aristocracy and Norman bluebloods, to a harpsichord-loving salonnière who corresponded with Benjamin Franklin, to a publisher whose father had owned several works by Fragonard, and a miniaturist who may have been a colleague of the artist’s wife. Fragonard’s drawing is a Rosetta stone whose implications are still to be fully interpreted and absorbed, despite the pioneering scholarship of several of the authors who have previously published on the series, many of whom contributed to the excellent volume under the direction of Yuriko Jackall, curator of the exhibition.

Is Fragonard’s drawing an installation plan for an ensemble that was commissioned for a gallery by one of the figures represented in Fragonard’s pantheon? (An unlikely hypothesis, but forcefully argued by the scholar Marie-Anne Dupuy Vachey.) Is it possible that the drawing was made from memory, and not in the presence of the pictures themselves, as a riccordo (souvenir)—perhaps after the ensemble was dispersed, since at least three of the “fantasy portraits” appeared on the Parisian art market by the mid-1770s? (This is suggested, implausibly in my view, by Jean-Pierre Cuzin, one of the doyens of Fragonard scholarship). Does the first sketch on the newly discovered sheet show the protagonist of the National Gallery of Art’s Reader—the only fantasy portrait not identified in this drawing—looking directly at the viewer, as in the original composition known from x-radiography (as argued by Jackall and her colleagues)? Or, as seems the most likely, does it indeed represent the young sitter in profile, exactly as she appears in the final version of the painting? Finally, what weight should be given to the proposition advanced in the 1840s by Fragonard’s grandson, Théophile (and developed by Pierre Rosenberg in his discussion of the series in 1988), that the artist had decorated his living quarters on the first floor of the Louvre’s Cour carrée with a gallery of his own paintings to be admired by the distinguished art lovers and collectors who visited him there, which he later sold for a considerable sum? While no further evidence has yet emerged to support this argument, it still seems the most likely explanation.

Like his spontaneity and bravura, Fragonard’s sociability—a rather overused term in current arthistorical scholarship—is willfully, if effortlessly, constructed. He is known to have enjoyed a close relationship with only one of the eighteen figures that comprise the series: the dashing abbé de Saint-Non, whom he had first met in Rome a decade earlier, and with whom he had travelled throughout the Italian peninsula between March and September 1761. As has often been noted, after Fragonard returned to Paris following a four-year stint as a royal pensionnaire at the French Academy in Rome, his relations with his patrons—the crown, the Academy, collectors of modern art—were generally uneasy, lacking the expected (and customary) deference. Fragonard failed to complete any of the decorative commissions awarded by the Crown, suffered the humiliation of having his series for Madame du Barry’s pavilion at Louveciennes rejected, and was obliged to take legal action against the Maecenas with whom he and his wife travelled to Italy between October 1773 and October 1774, because his patron had expected to keep possession of all the drawings that Fragonard made during that year.

Advertisement

Unlike what is known about Fragonard’s turbulent relationships with some of his most prominent patrons, the fantasy portraits communicate a far more reassuring cordiality. In them, Fragonard is indulging in the rich vein of nostalgia for a chivalric age, the bon vieux temps of the reign of Henri IV, also to be found in certain aristocratic theatricals of his day. Charles Collé (1709-1783), a now forgotten playwright and song writer attached to the Duc d’Orléans’s household, evoked a similar world in his three-act comedy, La Partie de Chasse, published in 1766. Here a cast of courtesans prepares for the hunt, attending the beloved monarch who radiates “an adorable bonhomie, which moreover, when present in a Prince, has a special dignity of its own.” A similar bonhomie adorable—real or imaginary—permeates every participant of Fragonard’s merry company.

“Fragonard: The Fantasy Figures” was on display at the National Gallery of Art through December 3, 2017. The largest group of fantasy portraits, seven in all, is on permanent display at the Musée du Louvre, Paris. In public institutions in America, The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and the Art Institute of Chicago each own one fantasy portrait by the artist.