Nobuyoshi Araki and Nan Goldin are good friends. This is not surprising, since the seventy-seven-year-old Japanese photographer and the younger American are engaged in something similar: they make an art out of chronicling their lives in photographs, aiming at a raw kind of authenticity, which often involves sexual practices outside the conventional bounds of respectability. Araki spent a lot of time with the prostitutes, masseuses, and “adult” models of the Tokyo demi-monde, while Goldin made her name with pictures of her gay and trans friends in downtown Manhattan.

Of the two, Goldin exposes herself more boldly (one of her most famous images is of her own battered face after a beating by her lover). Araki did take some very personal photographs, currently displayed in an exhibition at New York City’s Museum of Sex, of his wife Yoko during their honeymoon in 1971, including pictures of them having sex, and of her death from cancer less than twenty years later. But this work is exceptional—perhaps the most moving he ever made—and the kind of self-exposure seen in Goldin’s harrowing self-portrait is largely absent from Araki’s art.

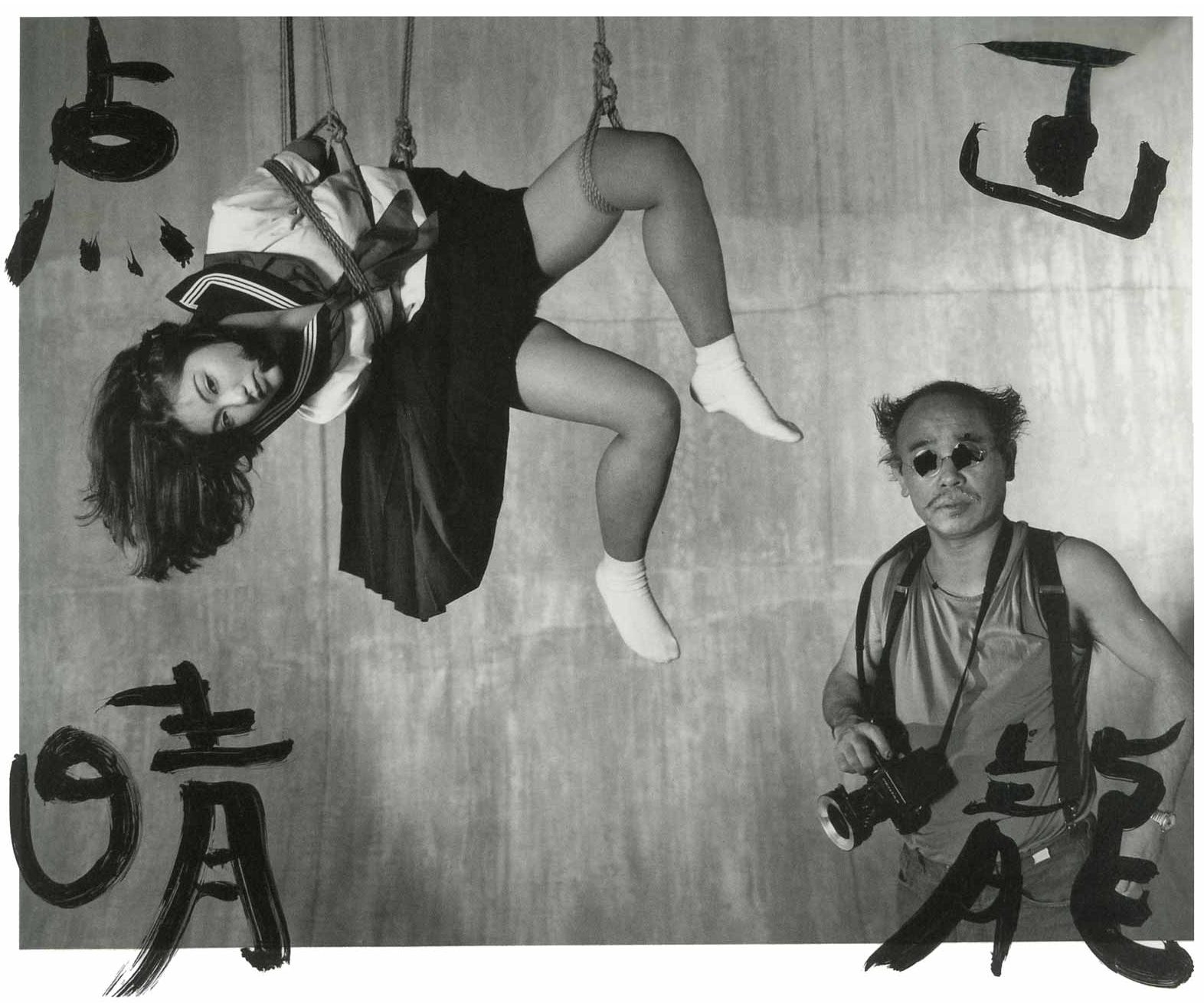

Araki is not, however, shy about his sexual predilections, recorded in thousands of pictures of naked women tied up in ropes, or spreading their legs, or writhing on hotel beds. A number of photographs, also in the current exhibition, of a long-term lover named Kaori show her in various nude poses, over which Araki has splashed paint meant to evoke jets of sperm. Araki proudly talks about having sex with most of his models. He likes breaking down the border between himself and his subjects, and sometimes will hand the camera to one of his models and become a subject himself. But whenever he appears in a photograph, he is posing, mugging, or (in one typical example in the show) holding a beer bottle between his thighs, while pretending to have an orgasm.

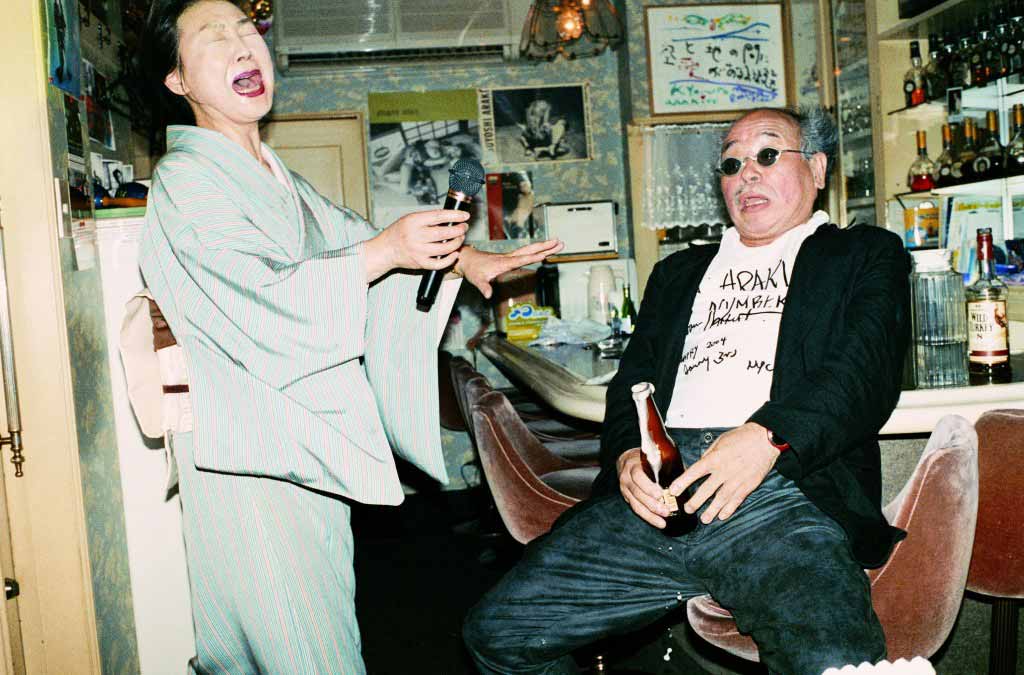

If this is authenticity, it is a stylized, theatrical form of authenticity. His mode is not confessional in the way Goldin’s is. Araki is not interested in showing his most intimate feelings. He is a showman as much as a photographer. His round face, fluffy hair, odd spectacles, T-shirts, and colored suspenders, instantly recognizable in Japan, are now part of his brand, which he promotes in published diaries and endless interviews. Since Araki claims to do little else but take pictures, from the moment he gets up in the morning till he falls asleep at night, the pictures are records of his life. But that life looks as staged as many of his photographs.

Although Araki has published hundreds of books, he is not a versatile photographer. He really has only two main subjects: Tokyo, his native city, and sex. Some of his Tokyo pictures are beautiful, even poetic. A few are on display in the Museum of Sex: a moody black-and-white view of the urban landscape at twilight, a few street scenes revealing his nostalgia for the city of his childhood, which has almost entirely disappeared.

But it is his other obsession that is mainly on show in New York. It might seem a bit of a comedown for a world-famous photographer to have an exhibition at a museum that caters mostly to the prurient end of the tourist trade, especially after having had major shows at the Musée Guimet in Paris and the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum. But Araki is the least snobbish of artists. The distinctions between high and low culture, or art and commerce, do not much interest him. In Japan, he has published pictures in some quite raunchy magazines.

The only tacky aspect of an otherwise well-curated, sophisticated exhibition is the entrance: a dark corridor decorated with a kind of spider web of ropes that would be more appropriate in a seedy sex club. I could have done without the piped-in music, too.

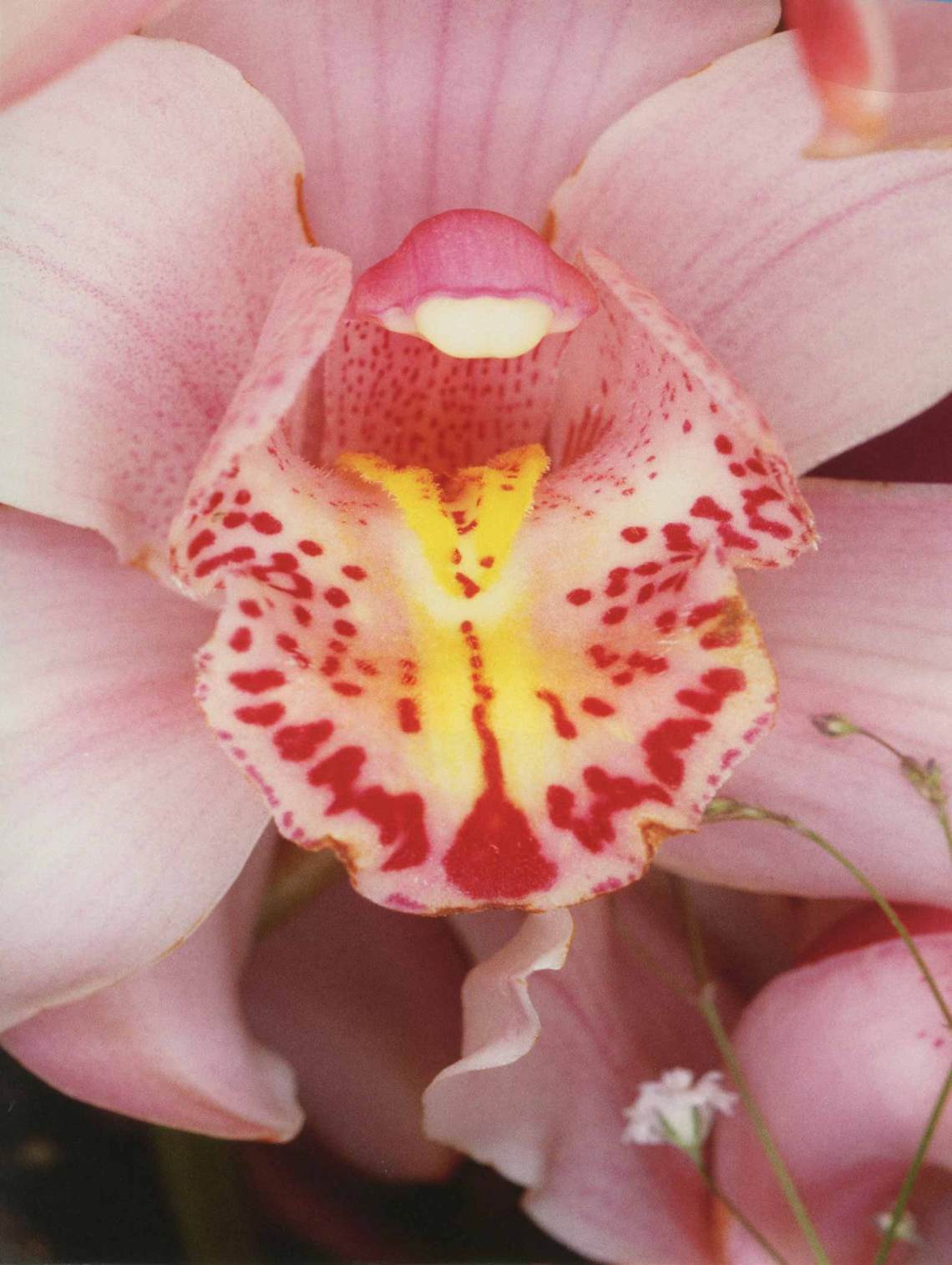

Sex is, of course, an endlessly fascinating subject. Araki’s obsessive quest for the mysteries of erotic desire, not only expressed in his photographs of nudes, but also in lubricious close-ups of flowers and fruits, could be seen as a lust for life and defiance of death. Some of these pictures are beautifully composed and printed, and some are rough and scattershot. One wall is covered in Polaroid photos, rather like Andy Warhol’s pictures of his friends and models, except that Araki’s show a compulsive interest in female anatomy.

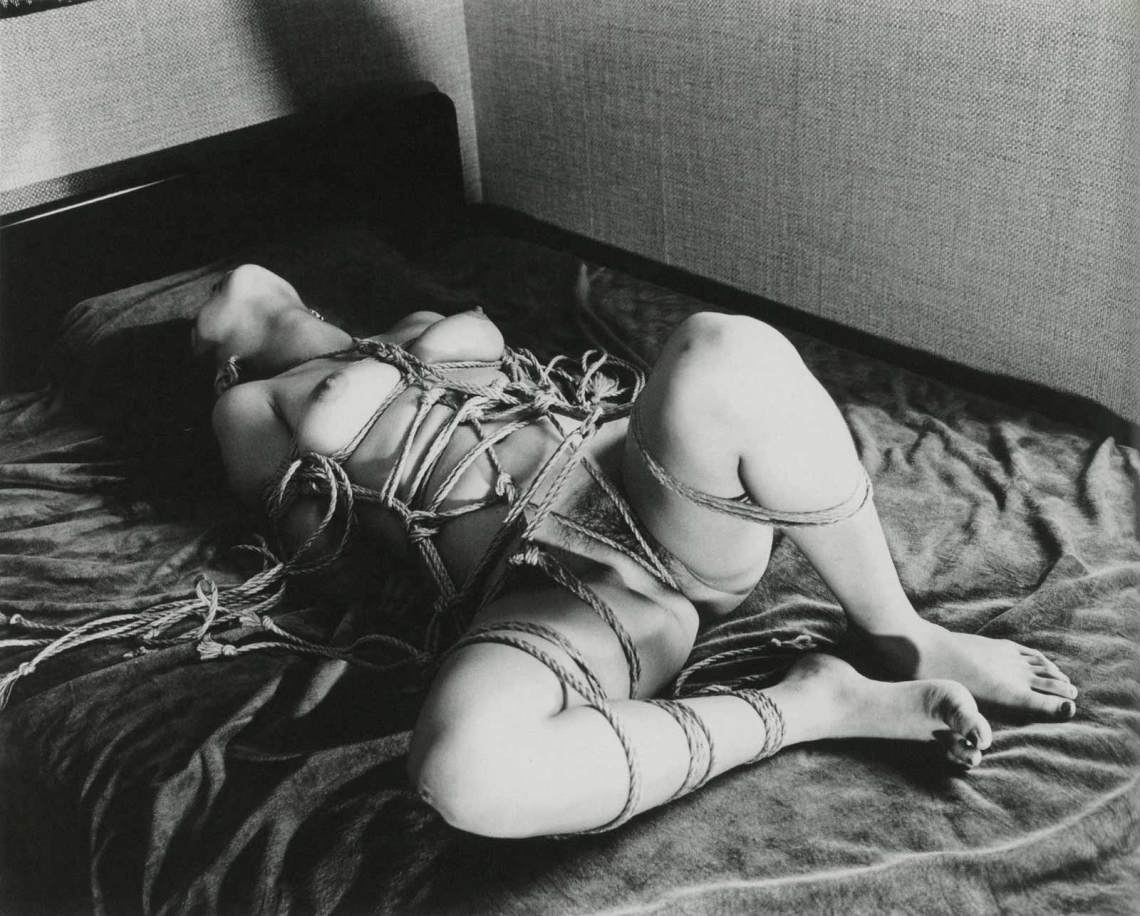

Genitalia, as the source of life, are literally objects of worship in many Japanese Shinto shrines. But there is something melancholy about a number of Araki’s nudes; something frozen, almost corpse-like about the women trussed up in ropes staring at the camera with expressionless faces. The waxen face of his wife Yoko in her casket comes to mind. Then there are those odd plastic models of lizards and dinosaurs that Araki likes to place on the naked bodies of women in his pictures, adding another touch of morbidity.

Advertisement

But to criticize Araki’s photos—naked women pissing into umbrellas at a live sex show, women with flowers stuck into their vaginas, women in schoolgirl uniforms suspended in bondage, and so on—for being pornographic, vulgar, or obscene, is rather to miss the point. When the filmmaker Nagisa Oshima was prosecuted in the 1970s for obscenity after stills from his erotic masterpiece, In the Realm of the Senses, were published, his defense was: “So, what’s wrong with obscenity?”

The point of Oshima’s movie, and of Araki’s pictures, is a refusal to be constrained by rules of social respectability or good taste when it comes to sexual passion. Oshima’s aim was to see whether he could make an art film out of hardcore porn. Araki doesn’t make such high-flown claims for his work. To him, the photos are an extension of his life. Since much of life is about seeking erotic satisfaction, his pictures reflect that.

Displayed alongside Araki’s photographs at the Museum of Sex are a few examples of Shunga, the erotic woodcuts popular in Edo Period Japan (1603–1868), pictures of courtesans and their clients having sex in various ways, usually displaying huge penises penetrating capacious vulvas. These, too, have something to do with the fertility cults of Shinto, but they were also an expression of artistic rebellion. Political protest against the highly authoritarian Shoguns was far too dangerous. The alternative was to challenge social taboos. Occasionally, government officials would demonstrate their authority by cracking down on erotica. They still do. Araki has been prosecuted for obscenity at least once.

One response to Araki’s work, especially in the West, and especially in our time, is to accuse him of “objectifying” women. In the strict sense that women, often in a state of undress, striking sexual poses, are the focus of his, and our, gaze, this is true. (Lest one assume that the gaze is always male, I was interested to note that most of the viewers at the Museum of Sex during my visit were young women.) But Araki maintains that his photographs are a collaborative project. As in any consensual sado-masochistic game, this requires a great deal of trust.

Some years ago, I saw an Araki show in Tokyo. Susan Sontag, who was also there, expressed her shock that young women would agree to being “degraded” in Araki’s pictures. Whereupon the photographer Annie Leibovitz, who was there too, said that women were probably lining up to be photographed by him. Interviews with Araki’s models, some of which are on view at the Museum of Sex, suggest that this is true. Several women talk about feeling liberated, even loved, by the experience of sitting for Araki. One spoke of his intensity as a divine gift. It is certainly true that when Araki advertised for ordinary housewives to be photographed in his usual fashion, there was no shortage of volunteers. Several books came from these sessions.

But not all his muses have turned out to be so contented, at least in retrospect.

Earlier this year, Kaori wrote in a blog post that she felt exploited by him over the years (separately, in 2017 a model accused Araki of inappropriate contact during a shoot that took place in 1990). Araki exhibited Kaori’s photos without telling her or giving her any credit. On one occasion, she was told to pose naked while he photographed her in front of foreign visitors. When she complained at the time, he told her, probably accurately, that the visitors had not come to see her, but to see him taking pictures. (The Museum of Sex has announced that Kaori’s statement will be incorporated into the exhibition’s wall text.)

These stories ring true. It is the way things frequently are in Japan, not only in relations between artists and models. Contracts are often shunned. Borderlines between personal favors and professional work are blurred. It is entirely possible that Araki behaved badly toward Kaori, and maybe to others, too. Artists often use their muses to excite their imaginations, and treat them shabbily once the erotic rush wears off.

One might wish that Araki had not been the self-absorbed obsessive he probably is. Very often in art and literature, it is best to separate the private person from the work. Even egotistical bastards, after all, can show tenderness in their art. But in Araki’s case, the distinction is harder to maintain—this is an artist who insists on his life being inseparable from his pictures. The life has dark sides, and his lechery might in contemporary terms be deemed inappropriate, but that is precisely what makes his art so interesting. Araki’s erotomania is what drives him: aside from the posing and self-promotion, it is the one thing that can be called absolutely authentic.

Advertisement

“The Incomplete Araki: Sex, Life, and Death in the Works of Nobuyoshi Araki” is at the Museum of Sex, New York, through August 31.