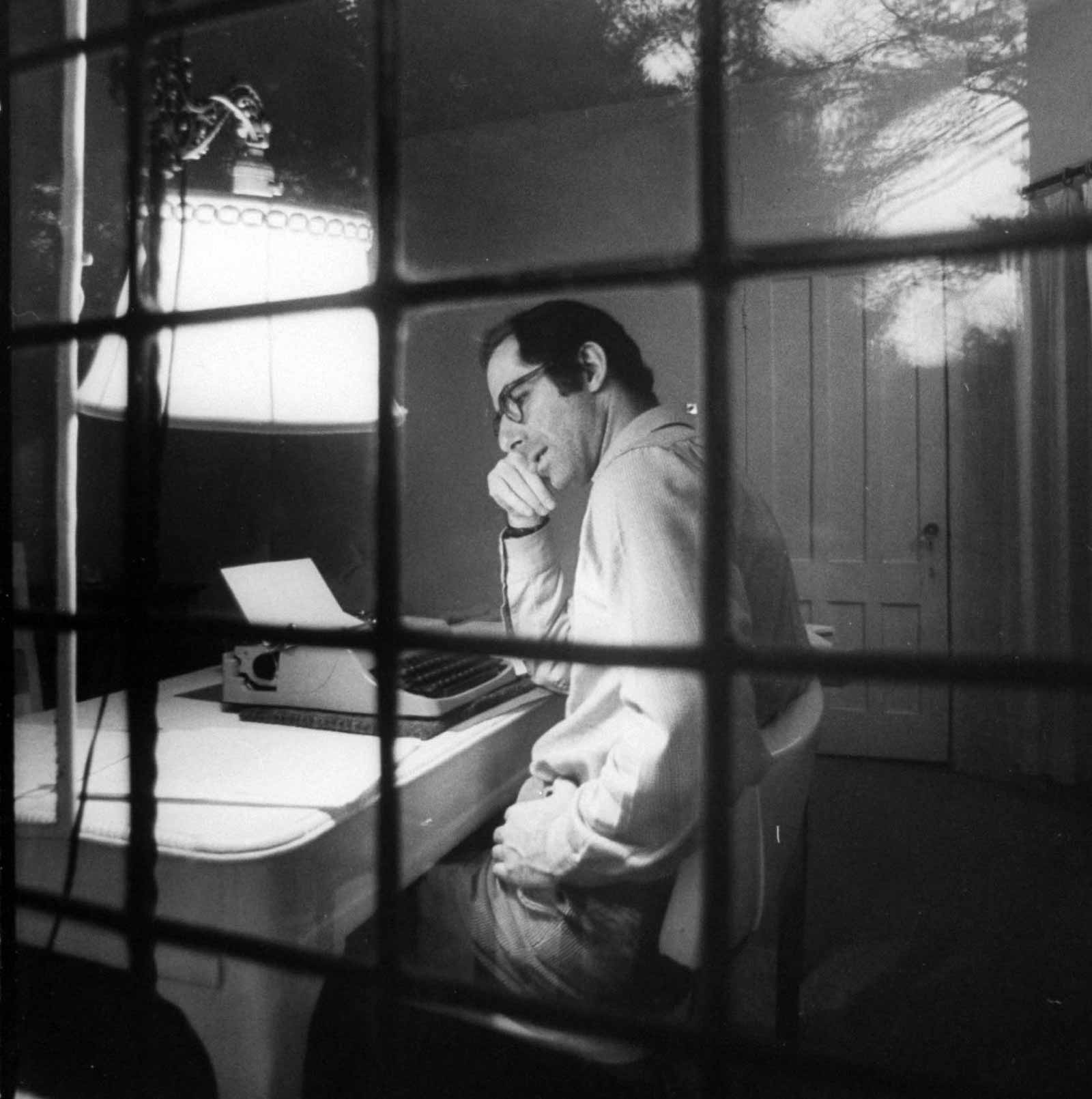

A life in literary criticism: how Review writers read and responded to the novels of Philip Roth (1933–2018).

LeRoi Jones, “Channel X,” July 9, 1964

One of the gaudiest aspects of the American Establishment, as nation, social order, philosophy, etc., and all the possible variations of its strongest moral and social emanations, its emotional core, is its need to abstract human beings. It is a process that leads to dropping bombs.

Mr. Roth, you are no brighter than the rest of America, slicker perhaps. »

Alfred Kazin, “Up Against the Wall, Mama!”, February 27, 1969

Roth is pitiless in reducing Jewish history to the Jewish voice. “Why do you suffer so much?” the Italian “assistant” jeeringly challenges the Jewish grocer in Bernard Malamud’s novel. To which the answer of course comes (with many an amen! from Jesus, Marx, Freud, and others too numerous to mention)—“I suffer for you!” “Why do I suffer so much?” Alex Portnoy has to ask himself in Newark, Rome, Jerusalem (Alex is lonely even in the most crowded bed). His answer, his only answer, the final answer, what an answer, is that to which many a misanthropic son of the covenant is now reduced in this mixed blessing of a country—“My mother! My… Jewish mother!”

This is still funny? In Portnoy’s Complaint it is extremely funny, and the reason that Roth makes it funny is that he believes this, he believes nothing else. »

Murray Kempton, “Nixon Wins!”, January 27, 1972

That Mr. Roth failed should finally interest us less than why he chose to run. But then he is particularly interesting as a novelist just because his good fairy kept his bad fairy from inflicting upon him one of those guardian angels who protect the writer from unseemly adventures and therefore from redeeming risks. Roth has continually striven, from love or hate or a bit of both, to explain America to himself; and that is why he has so steadily managed to give us work that, if it cannot always be judged as satisfactory, has been unexpected and, what is more to the point, exhilarating. »

Frederick C. Crews, “Uplift,” November 16, 1972

What makes an image telling, Roth accurately observed in his interview about The Breast, is not how much meaning we can associate to it, but the freedom it gives the writer to explore his obsessions. But has he explored his obsessions in this book, or simply referred to them obliquely before importing a deus ex machina to whisk them away? In a sense The Breast is a more discouraging work than the straightforwardly vicious Our Gang. Aspiring to make a noble moral statement, Roth quarantines his best insights into the way people are imprisoned by their impulses. What would Alex Portnoy have had to say about that? »

William H. Gass, “The Sporting News,” May 31, 1973*

So The Great American Novel is not about popcorn, peanuts, and crackerjack, or how it feels to sit your ass sore in the hot stands, but how the play is broadcast and reported, how it is radioed, and therefore it is about what gives the game the little substance it has: its rituals, its hymns, chants, litanies, the endless columns of its figures, like army ants, the total quality of its coverage, the breathless, joky, alliterating headlines which announce the doings of its mythologized creatures—those denizens of the diamond—everything, then, that goes into its recreation in the language of America: a manly, righteous, patriotic, and heroic tongue. »

Michael Wood, “Hooked,” Jun 13, 1974

My Life as a Man is a novel about not being able to write any other novel than the one you turn out to have written. The house of fiction becomes a house of mirrors, and this, presumably, is Roth’s problem as much as Tarnopol’s, since he did write thisnovel, and not another one. Fair enough: the problem is the theme, the novel enacts the problem. But then such arguments tend to fence with one’s doubts rather than make one entirely happy with the book. There remains a certain triviality there, a sense of the trap too eagerly embraced; an occasional sense of insufficient irony. »

Al Alvarez, “Working in the Dark,” April 11, 1985

What excites Roth’s verbal life—and provokes his readers—is, he seems to suggest, the opportunity fiction provides to be everything he himself is not: raging, whining, destructive, permanently inflamed, unstoppable. Irony, detachment, and wisdom are given unfailingly to other people. Even Diana, Zuckerman’s punchy twenty-year-old mistress who will try anything for a dare, sounds sane and bored and grown-up when Zuckerman is in the grip of his obsession. The truly convincing yet outlandish caricature in Roth’s repertoire is of himself. »

Gabrielle Annan, “Theme and Variations,” May 31, 1990

Roth is an aggressive writer. More aggressive than the Dadaists, or Henry Miller, or the Angry Young Men in Britain in the Fifties, or the Beat generation: he goes for the audience in the spirit of Peter Handke, who called one of his plays Offending the Audience. Roth challenges the reader to walk out, then woos him back again with cleverness and charm, and even an occasional touch of cuteness. Still, Maria walks out, and so does the mistress in Deception. »

Advertisement

Harold Bloom, “Operation Roth,” April 22, 1993

At sixty, and with twenty books published, Roth in Operation Shylock confirms the gifts of comic invention and moral intelligence that he has brought to American prose fiction since 1959. A superb prose stylist, particularly skilled in dialogue, he now has developed the ability to absorb recalcitrant public materials into what earlier seemed personal obsessions. And though his context tends to remain stubbornly Jewish, he has developed fresh ways of opening out universal perspectives from Jewish dilemmas, whether they are American, Israeli, or European. The “Philip Roth” of Operation Shylock is very Jewish, and yet his misadventures could be those of any fictional character who has to battle for his identity against an impostor who has usurped it. That wrestling match, to win back one’s own name, is a marvelous metaphor for Roth’s struggle as a novelist, particularly in his later books, Zuckerman Bound, The Counterlife, and the quasi-tetralogy culminating in Operation Shylock, which form a coherent succession of works difficult to match in recent American writing. »

Frank Kermode, “Howl,” November 16, 1995

Checking through the old Roth paperbacks, one notices how many of them make the same bid for attention: “His most erotic novel since Portnoy’s Complaint,” or “his best since Portnoy’s Complaint,” or “his best and most erotic since Portnoy’s Complaint.” These claims are understandable, as is the assumption that Roth is likely to be at his best when most “erotic,” but that word is not really adequate to the occasion. There’s no shortage of erotic fiction; what distinguishes Roth’s is its outrageousness. In a world where it is increasingly difficult to be “erotically” shocking, considerable feats of imagination are required to produce a charge of outrage adequate to his purposes. It is therefore not easy to understand why people complain and say things like “this time he’s gone over the top” by being too outrageous about women, the Japanese, the British, his friends and acquaintances, and so forth. For if nobody feels outraged the whole strategy has failed. »

Elizabeth Hardwick, “Paradise Lost,” June 12, 1997

The talent of Philip Roth floats freely in this rampaging novel with a plot thick as starlings winging to a tree and then flying off again. It is meant perhaps as a sort of restitution offered in payment of the claim that if the author has not betrayed the Jews he has too often found them to be whacking clowns, or whacking-off clowns. He bleeds like the old progenitor he has named in the title. Since he is, as a contemporary writer, always quick to insert the latest item of the news into his running comments, perhaps we can imagine him as poor Richard Jewell, falsely accused in the bombing in Atlanta because, in police language, he fit the profile; and then at last found to be just himself, a nice fellow good to his mother.

And yet, and yet, the impostor, the devil’s advocate for the Diaspora has, with dazzling invention, composed not an ode for the hardy settlers of Israel, but an ode to the wandering Jew as a beggar and prince in Western culture, speaking and writing in all its languages. »

Robert Stone, “Waiting for Lefty,” November 5, 1998

Who would have thought, forty years ago, it would be Philip Roth, the gentrified bohemian, who would bring remembered lilacs out of that dead land for us, mixing memory and desire? But the fact is that, besides doing all the other marvelous things he does, Roth has managed to turn his bleak part of Jersey and its people into a kind of Jewish Yoknapatawpha County, a singularly vital microcosm with which to address the twists and turns of the American narrative. In his most recent work, he has turned his aging New Jerseyites into some of the most memorable characters in contemporary fiction. »

David Lodge, “Sick with Desire,” July 5, 2001

One might indeed have been forgiven for thinking that Sabbath’s Theater(1995) was the final explosive discharge of the author’s imaginative obsessions, sex and death—specifically, the affirmation of sexual experiment and transgression as an existential defiance of death, all the more authentic for being ultimately doomed to failure. Micky Sabbath, who boasts of having fitted in the rest of his life around fucking while most men do the reverse, was a kind of demonic Portnoy—amoral, shameless, and gross in his polymorphously perverse appetites, inconsolable at the death of the one woman who was capable of satisfying them, and startlingly explicit in chronicling them. Even Martin Amis admitted to being shocked. Surely, one thought, Roth could go no further. Surely this was the apocalyptic, pyrotechnic finale of his career, after which anything else could only be an anticlimax.

Advertisement

How wrong we were. »

J.M. Coetzee, “What Philip Knew,” November 18, 2004

Just how imaginary, however, is the world recorded in Roth’s book? A Lindbergh presidency may be imaginary, but the anti-Semitism of the real Lindbergh was not. And Lindbergh was not alone. He gave voice to a native anti-Semitism with a long prehistory in Catholic and Protestant Christianity, fostered in numbers of European immigrant communities, and drawing strength from the anti-black bigotry with which it was, by the irrational logic of racism, entwined (of all the “historic undesirables” in America, says Roth, the blacks and the Jews could not be more unalike). A volatile and fickle voting public captivated by surface rather than substance—Tocqueville foresaw the danger long ago—might in 1940 as easily have gone for the aviator hero with the simple message as for the incumbent with the proven record. In this sense, the fantasy of a Lindbergh presidency is only a concretization, a realization for poetic ends, of a certain potential in American political life. »

Daniel Mendelsohn, “The Way Out,” June 8, 2006

And indeed, just as his allegedly ordinary hero can’t help being a vividly Rothian type, it’s hard not to see, creeping into Roth’s annihilating pessimism here, an irrepressible sentimentality. What, after all, does it mean to commune with the bones of one’s parents in a cemetery—a communication that involves not only the hero talking to them, but them talking back—if not that we like to believe in transcendence, believe that there is, in fact, something more to our experience than just the concrete, just the bones, just the bits of earth? If the scene is moving, I suspect it’s because of the nakedness with which it exposes a regressive fantasy that seems to belong to the author as much as to his main character: once again, Roth reserves his best writing and profoundest emotion for the character’s relationship with his parents. This reversion to the emotional comforts of childhood seems to me to be connected to the deep nostalgia that characterizes this latest period of Roth’s writing (it’s at the core of The Plot Against America, too); it also seems to be something that Roth himself is aware of, and which, in a moment that is moving in ways he might not have intended, his everyman articulates. “But how much time could a man spend remembering the best of boyhood?” he muses during a sentimental trip to the New Jersey shore town he visited as a boy. It’s a question some readers may be tempted to ask, too. »

Charles Simic, “The Nicest Boy in the World,” October 9, 2008

His powerful new novel, Indignation, seethes with outrage. It begins with a conflict between a father and son in a setting and circumstances long familiar from his other novels going back to Portnoy’s Complaint, but then turns into something unexpected: a deft, gripping, and deeply moving narrative about the short life of a decent, hardworking, and obedient boy who pays with his life for a brief episode of disobedience that leaves him unprotected and alone to face forces beyond his control in a world in which old men play with the lives of the young as if they were toy soldiers. Roth’s novels abound in comic moments, and so does Indignation. His compassion for his characters doesn’t prevent him from noting their foolishness. »

Elaine Blair, “Axler’s Theater,” December 3, 2009

Among all the twinned characters in Roth’s body of work there is no starker contrast than that between Axler and Roth’s other would-be suicide (and performer), Mickey Sabbath of Sabbath’s Theater (1995). Sabbath’s life too has turned to shit, but his howl of grief is driven—for hundreds of pages—by a great vital force that seems inextinguishable. With The Humbling, the scope of the novel has shrunk to accommodate a subject who is stunned nearly silent by his loss. Axler is an ordinary man and cannot turn his own grief into scathing and hilarious soliloquy, and therefore into art. And the art that Axler knows so well offers no consolation. »

*Philip Roth, “Roth’s Novel,” July 19, 1973

In response to:

The Sporting News from the May 31, 1973 issue

To the Editors:

Please advise Professor Gass that I am too old to be grown up.

Philip Roth

New York City