In response to:

An Exchange on Columbia from the July 11, 1968 issue

To the Editors:

The nub of Dwight Macdonald’s reply [NYR, July 11], if I follow the drift correctly, is that I confuse violence with illegality. With all respect I suggest that the confusion is in the mind of my eminent friend. Violence and illegality overlap, but are far from being identical. Violence, as we know all too well, can often be legal; and certainly illegal action takes many non-violent forms. Mr. Macdonald grants that the act of holding Dean Coleman hostage was unjustified (though, somewhat cavalierly, he adds that since the Dean could have freed himself by a simple telephone call, this is “not a crucial charge”); but the occupation of university buildings, though illegal, was not in his view an act of violence. Indeed the only people he believes committed real violence were the police who were summoned to remove the trespassers.

Surely the time has come to specify what violence means before we get hopelessly enmeshed in quibbles. I propose the following home-made definition: violence is the use of force on the body or mind or property of another person or group against the wishes of that person or group and to the detriment of that person’s or group’s well-being or rights or both. Thus, if I decided for the most sincere and idealistic of motives to break into Mr. Macdonald’s apartment and to barricade the door so that he could not gain access, if I then rifled Mr. Macdonald’s desk to discover what I regarded as incriminating papers and, if finally I threw open the window and used a megaphone to broadcast my loathing of Mr. Macdonald’s views to all passersby, I should be committing acts of violence just as much as if I tweaked Mr. Macdonald’s beard or struck him with my umbrella or bombarded him with spitballs; and, however noble my aims might be, he would have every right to ask the police to remove me by force. The same would apply, mutatis mutandi, if I organized an occupation of the new SDS headquarters that he has helped to finance. And the same applies to the students who forcibly occupied the Columbia buildings and disrupted the work of our University.

Can such violence ever be justified? Mr. Macdonald declares that he is opposed to violence on principle but that he has lost some of his “bourgeois inhibitions about illegality.” Here I would actually go further than him and suggest that in certain conditions even violence, repugnant as it must invariably be, is justifiable. If a person or group lives in a society where his or other people’s fundamental rights are intolerably curtailed for a protracted period of time and in which the infliction of such violence is the only remaining method that may effectively remedy the situation, then the infliction of the least necessary amount of violence is, in my view, warranted. But the insurgent students at Columbia, “dull and mediocre” as Mr. Macdonald believes their existence to have been until this spring, were definitely not justified in using violence according to this or any other reasonable criterion.

Finally I must return to the destruction of Professor Ranum’s manuscripts, a violent act that I take to be of particular symbolic importance. Mr. Macdonald says that “not many of us jumped to the soggy conclusion” that the students were responsible. I have no idea who “us” may be; but I do know that I was constantly at Columbia during the disturbances and that I never met one person, even among those most sympathetic to the demonstrators, who doubted that it was their doing. According to Mr. Macdonald, the student leaders had too much common sense to commit such an act, and he suggests that the culprits may have been “police provocateurs.” If he actually believes that, he can believe anything.

Whoever may have been responsible for the destruction, Mr. Macdonald evidently regards it as “one of the risks of any rebellious effort to shatter an undesirable status quo” or, to revert to the cozy old image, one of the eggs that must be broken to make an omelette. I take it that the right to make omelettes in this fashion is restricted to people whose objectives Mr. Macdonald happens to support.

Ivan Morris

Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures

Columbia University

New York City

Dwight Macdonald replies:

Ivan Morris now proposes a “home-made definition” of “violence” that fits his argument like a glove. But if controversialists bully words in this Humpty-Dumpty style, discussions won’t get far. “The question is who is to be master,” Mr. Dumpty explained to Alice, adding that he paid extra when he made his words work hard, as when “glory” had to mean “a nice knockdown argument.” I’d rather not think how much overtime Professor Morris had to pay “violence.” So let’s try a real, manufactured definition, one in a dictionary. The two on my desk give: “Proceeding from or marked by great physical force or roughness; overwhelmingly forceful” (Funk & Wagnalls) and “Acting with or characterized by uncontrolled, strong, rough force” (Random House). I think my eminent friend would have to agree that these don’t describe the tactics of the student strikers and do describe those of the police when they were called onto the campus, twice, by Dr. Kirk and Dean Truman to help them run their university.

Advertisement

The analogy between the taking over of President Kirk’s office and a hypothetical occupation by Professor Morris of my apartment fudges over the difference between the personal and the professional, spheres—making distinctions isn’t his forte. It takes a heap o’ living to make an office a home, and although from Dr. Kirk’s laments about the brutalization of his office—he was so shook up that he forgot to express similar regrets about the brutalization of his students by the cops he called in—one realized that to an inured bureaucrat his office is his home, still, in the real, or non-bureaucratic, world, the students took over an office, a more legitimate object of occupation because of its public, professional function. If my friend and his cronies hijacked my office, I’d temporize, partly because I’d be curious to see what their “rifling” of my disordered correspondence files turned up and partly because I would recognize an obligation to negotiate, really negotiate, not just in form.

On the burning of Dr. Ranum’s research papers: I gave three possibilities: “perhaps some nut fanatics from among the students, perhaps ditto from outside the campus, perhaps police provocateurs.” I did judge it unlikely—giving reasons—that the strike leaders had anything to do with this disgusting, and counter-productive, act of petty revenge. Now Professor Morris omits the first two categories and implies the cops were my chief suspects, adding he’s never met any one “even among those most sympathetic to the demonstrators, who doubted it was their doing.” But whose doing? The responsible leaders, or some irresponsible followers? It makes quite a difference—as noted, distinctions aren’t his strongest point—and until our police, who seem better at cracking skulls than at sleuthing, on the Columbia campus at least, solve the crime, he knows just what to do about it, which is nothing.

And why does my friend assume he’s won the argument when he triumphantly concludes: “I take it that the right to make omelettes in this particular fashion is restricted to people whose objectives Mr. Macdonald happens to support.”? Oh dear, more distinctions. As a supporter, and former board member, of the New York Civil Liberties Union, let me state the obvious: (1) There is no general moral “right” to break the law as the student strikers did when they occupied the buildings (or as the 1936 sitdown strikers did when they occupied the Detroit automobile plants). (2) Whether one supports such actions or not depends on (a) whether one agrees with the aims of the law-breakers, (b) whether one thinks the actions, the means are congruent with the ends and so won’t corrupt or subvert them, and (c) whether one believes that lawful means have been tried and have failed. I’ve recently conspired with Dr. Spock, Chaplain Coffin and many others I know as well as I do them, which is hardly at all, to give support and encouragement to young men who violate the Selective Service Act; I’m also refusing to pay 25 percent of my Federal income tax; both illegal actions that seem to me—as those of the Columbia strikers did—to satisfy requirements (a) (b) and (c) given above. (3) Therefore, if the jocks or the Birchers take over Hamilton Hall and refuse to leave until the Trustees agree to begin building again that unfortunate gym in Morningside Park (this time on a lily-white basis, no place for the black community at all, top or bottom, segregated or not) when they appeal to me for support, enclosing a marked copy of my friend’s letter, I’ll have to say sorry, all a misunderstanding, you’re on your own, baby, as far as I’m concerned.

Finally, Professor Morris’s letters do raise, in however muzzy a form, a serious problem. I tried to meet it in some of my remarks at a para-Commencement mounted by the strikers on the campus last spring while the official one was going on at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine:

“While I find your strike and your sitins productive, I don’t think these tactics can be used indefinitely without doing more damage than good to the university. It would be a pity if Columbia became another Latin American type of university in which education is impossible because student strikes and political disruptions have become chronic. Nor do I think that our universities should be degraded to service as entering wedges to pry open our society for the benefit of social revolution. I’m for such a revolution but I don’t think it is a historical possibility in the foreseeable future in this country, and premature efforts to force it will merely damage or destroy such positive, progressive institutions as we have. Their only effect—if any—will be to stimulate a counter-revolution which will have far more chances of success.

Advertisement

“An example of this kind of tactics—one can hardly call it thinking—is a recent manifesto by Tom Hayden in the June 15th issue of Ramparts. ‘The goal written on the university walls,’ he begins, ‘was “Create two, three, many Columbias” [a reference to the late Che Guevara’s “Create two, three, many Vietnams in Latin America”—one is enough for me, and also his effort didn’t turn out a very solid enterprise, speaking in terms of history, not rhetoric]. It meant expand the strike so that the US must change or send its troops to occupy American campuses…. Not only are these [Columbia] tactics already being duplicated on other campuses, but they are sure to be surpassed by even more militant tactics. In the future it is conceivable that students will threaten destruction of buildings as a last deterrent to police attack. Many of the tactics learned can also be applied in smaller hit-and-run operations between strikes; raids on the offices of professors doing weapons research could win substantial support among students while making the university more blatantly repressive…. The Columbia students…did not even want to be included in the decision-making circles of the military-industrial complex that runs Columbia…. They want a new and independent university standing against the main-stream of American society, or they want no university at all. They are, in Fidel Castro’s words, “guerrillas in the field of culture.” ‘ ”

This program might be called “Building Socialism in One University” and it would have the same effects on the campus as Stalin’s “Building Socialism in One Country” did on the Soviet Union; as in that case, the means would vitiate the ends and the result of Hayden’s “hit-and-run operations,” raids on professors’ offices and chronic guerrilla warfare would be not socialism, and certainly not culture, but a Hobbesian chaos of mindlessly reflexive “confrontations”—how he gloats over provoking the academic authorities into becoming “more blatantly repressive”!—about which a safe prediction is that it would undoubtedly be nasty, brutish—and short. An even safer prediction is that the campuses won’t be Haydenized. A lot of capital has gone into our universities, and the bourgeois trustees and state legislators who control them are not about to turn over these plants to Mr. Hayden’s, and my, revolution. He talks grandly of “the students” throughout his article, but this is as undiscriminating as Professor Morris’s references to “the demonstrators”. A majority of Columbia students responded to the SDS initiative because the demands were limited and reasonable—a brighter administration would have granted them before things got ugly, and “the military-industrial complex” wouldn’t have been even dented—but, in a recent (June 6th) poll by Columbia’s Bureau of Applied Social Research (C. Wright Mills was its co-founder) only 19 percent of the student respondents favored (as Mr. Hayden and I did) the tactics of the demonstrators, while 68 percent were against them. The actual occupation of the buildings was carried out by a large group—about 700, many of them Barnard girls—but it was still very much a minority, and even among these activists there was dissent from some of the more “militant” and uncompromising tactics of the SDS leadership, as in the big Fayerweather Hall “commune.”

The para-Commencement at which I spoke, for example, was organized not by the SDS but by the Students for a Restructured University, who had split from the SDS-dominated strike committee because they had the same objections to Building Socialism in One University that I expressed above. (The SDS was dubious up to the last day, when they did join, worried lest even a mock imitation of the real thing was not too great a concession to bourgeoisdom, since parody implies some parallelism.) The other speakers were two university chaplains, Jewish and Protestant, Dr. Ehrlich of the Economics Department, Harold Taylor, and Erich Fromm, and it was a beautiful occasion, spirited and friendly and dignified, with an audience of some 4,000, including 300 members of the graduating class in their caps and gowns.

WHEN Columbia reopens this fall, I hope there will be no more High Noon showdowns between the Kirk administration and the SDS revolutionaries, and that both will compromise their principles for the sake of Columbia—and of sanity. The SRU has received a grant of $10,000 from the Ford Foundation to study and formulate proposals for reform, and something may come of this. Before Ivan Morris writes a third letter asking why I raised funds for the SDS instead of the SRU, let me explain that the former asked me and the latter didn’t, perhaps because it wasn’t in existence at the time; also that SDS is broader, and looser, than its Haydenesque and Ruddite infantile ultra-leftists (and I even like their spirit); and finally that the strike was needed and that the SDS lit the fuse. “If we succeed in reforming Columbia,” John Thoms of the SRU is quoted in the June 10 Times, “it will be because of the radicals.” I agree with him.

The threat to Columbia this fall will come not from the SDS but from the petty, vindictive and inept policies of the Kirk-Truman administration. By refusing to drop criminal trespass charges against hundreds of demonstrators and by supplementing them with suspensions, President Kirk and the Trustees are sailing their ship into the minefield that blew it up last spring, setting the stage for a second round of student protest, police violence, and general uproar (this time, it won’t be so creative, I think, and much more unpleasant). If Columbia is ever Guevaraized, the credit will go to Dr. Kirk more than to Tom Hayden. The new undergraduate dean, Carl Hovde, wants the criminal charges dropped but is against academic amnesty for the strikers. Most of the faculty (78 percent) and even the students (70 percent) agree with him. The usual argument is that if you violate the rules, or the law, as a demonstration of principle, it is not logical to ask to be let off paying the penalty. Maybe not logical but standard procedure in the other kind of strike: the first union demand is always that strikers shall be rehired without discrimination and that illegal acts of pickets shall not be prosecuted by the company. The 1936 Detroit sit-in strikers occupied far more valuable properties than five college buildings and for a much longer time, causing losses of hundreds of millions to the automobile companies, but the settlement of the strike provided no punishment for them. Of course, they won. And the demonstrators so far have not won. But let’s be clear: the denial of amnesty is for that reason, not because of any moralistic nonsense about paying the price, etc. The Columbia bureaucrats think they can operate without settling the strike, i.e., granting amnesty. I don’t. We’ll soon see which view is right.

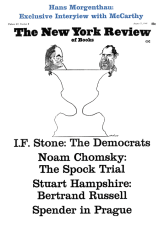

This Issue

August 22, 1968