Douglas Brown is a conservative English journalist who lived for five years in South Africa. He has sympathy, and even admiration, for the Afrikaners, but disapproves, on grounds of Christian principle, of their practice of apartheid. He sees their predicament as tragic, its outcome as probably cataclysmic; he strongly dislikes liberal criticism of South Africa, and condemns any effort to change the system by external intervention. His divided feelings about South Africa, and the intensity of his concern with its problems and solutions, make him an exceedingly alert observer. He writes well himself, and has a good ear for the revealing word and phrase. Nobody, I think, has written more illuminatingly about his narrow but important subject: “attitudes of white South Africa.” His book has been banned in South Africa.

Edward Feit is a political scientist educated in South Africa, and now at the University of Massachusetts. His book is a “study in depth” of two passive resistance campaigns conducted by the African National Congress—that against the clearances of the “black spots” of Johannesburg in 1953-54, and that against “Bantu Education” in 1954-55. Based on newspaper material and on the documents of the 1959-61 Treason Trial, African Opposition shows why these movements failed. Tribal and class divisions; uneasy relations between different categories of non-whites; competition for scarce housing and scarce teaching; remoteness of intellectuals from the masses; real wages rising slowly, but rising; organizational weakness, resulting in part from great distances, differences in local situations and attitudes, and from poverty, defective communications, defective information, and lack of discipline—all these were sources of weakness in the African National Congress, offsetting the great numerical superiority of the constituency to which it appealed. The Nationalist Government, on the other hand, disposed of the wealth of South Africa and controlled the State’s apparatus of repression, intimidation, communication, and cajolement; it represented a community with a sense of common interest outweighing all internal differences; it had at its core Africa’s most formidable and united tribe, the Afrikaner Calvinists. These advantages more than offset the numerical inferiority of white South Africa. Mr. Feit’s analysis deserves study, and most of it carries conviction. It is not easy to see what he thinks about the wider implications of his analysis; he uses the cumbrous dialect of his trade—“the South African government…greatly lacked symbolic appeal to the Africans”—a dialect which implies a claim to impartiality. He seems, however, to be of the opinion that, on the whole, the Africans of South Africa have reason to be contented with their lot and—with the exception of intellectuals and agitators—are generally fairly contented. He notes the existence of “irksome disabilities” from which they suffer but allows for “the vast improvements of recent years.” What these vast improvements are, he does not say; all other writers, except for the propagandists of the South African Government, agree that the “disabilities” which “separate development” imposes on non-whites have become more, not less, irksome in recent years.

E. J. Kahn, Jr., the New Yorker staff writer, spent three months in South Africa in 1966, and The Separated People is the pleasantly written record of his impressions. “South Africa today,” he writes in an introductory note, “can inspire convulsive arguments, but there is surely one unarguable aspect of that many-faceted country: it stands second to none when it comes to gracious hospitality.” Basil d’Oliveira1 might possibly not find this “unarguable.” Not that Mr. Kahn is gullible, or uncritical. He has a good journalistic nose and his exposure of, for example, some of the realities of the Transkei Bantustan is all the more valuable in that his report cannot be discounted for anti-South African feeling, or any other form of zeal. As he honestly says, he liked South Africa, and in the relatively short time he was there, he got as used to apartheid as he did to “the gorgeous scenery.” This prompts the thought that the peculiar institution could probably be exploited in tourist advertisements quite as effectively as the scenery: “Come to sunny South Africa, land of injustice, oppression, and gracious hospitality. Relax on our beaches, shudder at our jails. Savor the delicious thrill of releasing your pent-up indignation. When you get home.”

John Laurence is a British advertising man who spent ten years in South Africa. The Seeds of Disaster is in great part an indictment of apartheid, and one may question the utility of such an exercise at the present stage. The evils of apartheid are generally known, vocally condemned, and quietly condoned; a renewed indictment is not likely to alter these reactions. The most interesting parts of Mr. Laurence’s book are those in which he draws on his professional experience and gives an account of South Africa’s propaganda aims and methods, both at home and abroad. He prophesies large-scale propaganda exploitation of small apparent retreats from “total apartheid,” a condition which in any case never existed in the material world. Mr. Laurence gives the best definition I have seen of what apartheid has meant in practice: “the basic rule of this policy is…that the Bantu must stay apart from the White man unless the White man wants something.”

Advertisement

The Long View is a collection of articles by Alan Paton, published mainly in the liberal South African periodical Contact—which now survives only as an occasional mimeographed publication—during the period 1958-67. The earlier pieces are relatively hopeful, reflecting the feeling of imminent liberation of the period of Macmillan’s “wind of change” speech. The later pieces are very near despair: “For how long will this future last? My answer is ‘I do not know.’ To me there is another question: ‘How long can I last?’ And there is still another question: ‘Is it worth trying to last?”‘ Alan Paton is a brave and lonely man. He has been criticized as an ineffectual liberal; and he has been ineffectual, on any but a very “long view” indeed. His “tougher” critics have been equally ineffectual. He continues to live in South Africa. His advice to the South African readers of Contact is “Beware of melancholy and resist it actively if it assails you; and give thanks for the courage of others in this fear-ridden country” (1965).

The Central African Examiner, edited by Theodore Bull, ceased publication in 1965, as a result of the strict censorship imposed by the Smith Government. Mr. Bull himself now lives in Zambia. Rhodesia: Crisis of Color is a collection of papers by the editor and staff members of the Examiner. The most interesting part of the book is the concluding section, in which it is suggested that South Africa’s sphere of influence may come to include not merely Rhodesia and Malawi, but also Zambia; and that, if Smith’s “white Rhodesia” does not prove ultimately successful, South Africa might settle for “a black government in Rhodesia…willing to cooperate with South Africa”—as the governments of Botswana and Lesotho are willing and that of Swaziland will be willing. As Angola and Mozambique are increasingly dependent on South Africa, the whole of Southern Africa, up to the borders of the Congo and perhaps beyond that would become the sphere of influence of the Republic of South Africa—with the black Bantustans standing in much the same relation to the Republic as the Caribbean states do to the US. The African “wind of change” is, for the present, blowing from the South.

“SOUTH AFRICA,” says Douglas Brown, “only mirrors the world at large” South Africa, according to John Laurence, “is a nation with a vested interest in tragedy.” Both remarks contain truth. The South African laager (defensively organized camp) is a dramatically concentrated expression of the position of whites in the world. South African whites do have a clear interest in the exacerbation of racial ill-feeling elsewhere, and specifically in encouraging and appealing to white hatred and fear of blacks, especially in America and Britain. They are fully conscious of this interest. The Chairman of the Broederbond—the Afrikaner secret society which “runs the country” (Kahn)—made a most important statement on this subject in 1965, over the radio of the South African Broadcasting Corporation, of which he also happens to be Chairman. “South Africa,” he said, “has given this group [“the Western community of peoples outside Europe”] the lead in the racial struggle of the present and the future. South Africa will make a decisive contribution to the consolidation of the entire West as a White world united in its struggle against the joint forces of the yellow and black races of the Earth…When America reaches this level of maturity in the emergent world period, overcoming the transitional sickness of the modern period and taking over the leadership of the whole White world, the West will be very favourably placed to win the racial struggle on a global scale.”

In the few years that have passed since this remarkable utterance, members of the Broederbond and their followers must have followed social and political developments in America with great and hopeful interest. From their point of view, signs that America may be approaching the desired “level of maturity” have not been lacking. Their “vested interest in tragedy” is a specific vested interest in an American tragedy. For the security of the Republic of South Africa, and the security of its expansion, the more American whites are frightened, and blacks isolated, the better it will be. South Africa does not absolutely need a fascist America, although that would of course be the ideal solution. But the emergence in America—not merely in the South but throughout the country—of an identifiable anti-black vote with a stable and effective preponderance over the black vote would suffice.

Advertisement

Such a development, it might be assumed, would be accompanied by such modifications in the area of “law and order” as to make it self-perpetuating. And American foreign policy would move from the present furtive and shame-faced collusion with South Africa to open partnership and the recognition of a sphere of influence. There would be a transitional period in which the voting pattern at the United Nations would shift in South Africa’s favor. America would not then “fly in the face of world opinion”; the pattern of what is called “world opinion” is significantly modified (though not entirely transformed) by any major shift in America’s position.

Broederbonders who cherish some such vision of the future may be over-optimistic, yet their vision now seems considerably less fantastic than it would have seemed to outsiders at the time of the Chairman’s address in 1965. White South Africa knows how a State enjoying a limited but real democracy (a democracy which was not always strictly confined to whites), an independent judiciary, and a free press can turn—while still preserving the outward forms of all this—into a one-party police state. This must give them satisfactory food for thought as they contemplate present trends in American politics; it must also give food for thought to American rightwing politicians who have considered South African precedents.

THERE HAVE BEEN relevant developments since these books were written. Thus John Laurence, having chronicled the fact that anti-apartheid demonstrators of the “Black Sash” movement were first assaulted by thugs and then arrested by the police, adds: “In future, any South African citizen peacefully protesting against his government’s policies could not depend on the police to come to his aid if he were assaulted. And if he asked the police to defend him, he was liable to be arrested.” Mr. Laurence obviously expected his American readers to be shocked by such a situation. Yet by the time his book was published it had become commonplace in America that people “peacefully protesting against their government’s policies” should be assaulted, not only by unofficial thugs but by policemen, in or out of uniform. The behavior of the Johannesburg police, as recorded by Mr. Laurence, was a model of decency and restraint by comparison with the behavior of the Chicago police, as recorded by the press of America and of the world. And the most liberal of the three Presidential candidates, present at Chicago, condemned the victims of the uniformed mob, and praised that mob’s employer.

Classical theory holds the independence of the judiciary to be a barrier to the emergence of an authoritarian state. South African practice, however, shows how this independence may be respected, preserved, and by-passed. “Most of South Africa’s judges are men genuinely dedicated to justice,” writes E. J. Kahn Jr., “but when it comes to the detention laws they have remained uncommonly silent. ‘We’re supposed to be non-political and the government tells us there is an emergency,’ one Supreme Court justice told me.” Douglas Brown tells us what happens to a man who is “banned” by the Government under the Suppression of Communism Act (1950):

The impeccable jury, the able bar, the freedom that has broadened down from precedent to precedent became, in his case, suddenly irrelevant…. The blow falls silently, in the midst of a society where the full apparatus of civil liberty2 continues to function…. A university professor, a journalist, a novelist receives a letter that quietly turns him into a no-person.

The government, after all, declares that there is an emergency, and it would be hard to say that the government is wrong. It would also be hard to say that emergencies are not threatening in other countries and may not be met by similar means, giving a new content to democratic and liberal forms.

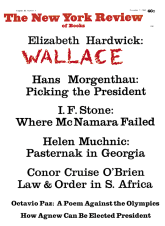

“Beware of melancholy,” says Alan Paton. Le pire, said Paul Claudel, n’est pas toujours le plus sûr. England, in 1912-14, at the time of the crisis over Home Rule for Ireland, seemed nearer to what was later to be called fascism than America does now. The comparison is not wholly encouraging. It was the holocaust of the First World War that saved liberal democracy in England, as the Second World War saved it in Western Europe. The peace of spheres-of-influence and nuclear balance may conceivably be more congenial to the rise of quieter forms of authoritarianism: liberal police states confronting socialist police states, in an unspoken racist collusion. If we feel—as this reviewer at present does—that the white world may be beginning to enter such a tunnel, with no light visible at the end of it for our generation, we must look at South Africa with a sickening sense of recognition of features which form part of our own condition and of our own future. Like Alan Paton we must derive such comfort as we can from “the long view.” Reading Paton, at first we feel sorry for him, an unwilling inhabitant of the laager, talking to the few other inhabitants3 who are also unwilling. Then we4 realize that the essentials of our position are the same as his, though our laager is larger, and less immediately threatened. The “though” is important, and so also are historical differences: if Paton in his position does not altogether give way to “melancholy,” we certainly should not do so. If, none the less, the present review is touched by nightmare, this is the natural consequence of reading six books about South Africa during a period preceding an American General Election in which the candidates are Nixon, Humphrey, and Wallace.

This Issue

November 7, 1968

-

1

The colored cricketer picked to join the England tour of South Africa. The South African government cancelled the tour, on the ground that the selection of the colored player was “political.”

↩ -

2

The “full apparatus” is now of course for the white minority only. It is surprising how often even critical commentators on South Africa fall into the white South African habit of treating non-whites as “no-persons.”

↩ -

3

The laager is, of course, exclusively white.

↩ -

4

The writer is white.

↩