In response to:

A Doll's House from the March 11, 1971 issue

To the Editors:

Since Elizabeth Hardwick has sought to marshal the relevant facts regarding Ibsen in his relation to women [NYR, March 11], perhaps you may be interested in a footnote, which however seems to me of very considerable importance.

The fact is not reported by Koht in his landmark biography; and so far as I know, it is not stated in any other convenient reference, either. Nonetheless, our understanding of Ibsen’s motives will be greatly helped if we know that during his years of apprenticeship in a provincial Norwegian pharmacy, he had an affair with a servant woman ten or so years older than himself, also employed there. A child, a boy, was born of this sexual encounter. Whatever ultimately became of this illegitimate son has never been made clear—perhaps it is not known. As for the legitimate son of Ibsen; he went on to become the Norwegian Foreign Minister and thus was a most respectable credit to the poet and playwright, who was ostentatiously proper for public consumption.

But not only had Ibsen his sexual fling with the liveborn result that he never brought himself to acknowledge. Through twenty-one years, until the illegitimate child reached his majority, the sheriff would be at Ibsen’s door every month to collect the support payment.

When we read Ibsen with or without the women’s movement in mind, and we come across the specters of guilty secrets, and the revenge of the past, the destruction of precious possessions, or the loss of a child—this suppressed fact of the illegitimate and rejected child in Ibsen’s own life should be granted the biographical weight it undoubtedly calls for.

Lee Baxandall

New York City

Elizabeth Hardwick replies:

In the revised edition of Halvdan Koht’s Life of Ibsen, the incident Baxandall mentions is very briefly stated: “These years brought many humiliations to the young man, but worst of all was the shame he felt when a servant girl, fully ten years older than he, bore him a child. Ibsen was just eighteen then, and for the next fourteen or fifteen years had to pay for the support of his son.” I am sure, as Baxandall says, that this incident was far more important than the brief account of it would suggest and I am grateful to him for pointing that out.

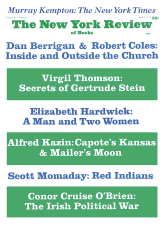

This Issue

April 8, 1971