Zinaida Hippius, who lived from 1869 to 1945, is considered one of Russia’s finest poets, perhaps her greatest religious poet. D. S. Mirsky speaks of the major cycle of her lyrics as “unique in Russian literature…so original that I do not know anything in any language that resembles them.” Pure in diction, unique in form, they are a despairing lament on the soul’s failure to conquer pettiness, on what Mirsky calls “the Svidrigailov theme” (the idea which, in Crime and Punishment, Svidrigailov tries out on Raskolnikov, that eternity itself may be nothing more than a dusty bathhouse filled with spiders). There is, for example, in a lyric called “She,” a sense of evil and self-hatred even more harrowing, because more articulate, than Svidrigailov’s:

She is gray as dust, as earthly ashes,

In her shameless, despicable vile- ness.

And I am perishing from just such nearness,

From this inseparable bond which joins us.And she is scabrous, yes, and she is prickly,

And she is cold. She is a serpent too.

And her repulsive, searing, over- lapping

Snake scales have wounded me as few things do.If only I could feel a sharp sting twinging!

But she is flaccid, still, with dull veneer.

She is so like a lump, so very sluggish.

One cannot get to her; she cannot hear.Coiling around me, stubborn, insinuating,

She hugs and strangles me, crush- ing me whole.

And this thing that’s so dead, so black, so frightful—

This wretched, loathsome thing is called my soul.

(translated by Merrill Sparks)

As a novelist, short story writer, and literary critic she is less remarkable. She was the wife of Dmitri Merezhkovsky, much better known but far inferior to her as an artist. In pre-revolutionary Russia and abroad she was also the exponent of a religious philosophy of her own devising; and it is with this philosophy that Professor Pachmuss is chiefly concerned, not with her art—about which there is just enough to suggest its flavor—nor with her biography.

The “philosophy” of Zinaida Hippius, one gathers, was a highly cerebral religious scheme, based on a faith in the mystic significance of numbers, especially of the holy number three, which was an attribute of the world and humanity as well as of the godhead. History was divided into three periods, the Old Testament and the New in the past, and the Third Testament of the future. Ethics was threefold: personal, sexual, and social. And the sexual act could be represented by an isosceles triangle, of which the horizontal line stood for the “earthy” union of man, the left corner, and woman, the right, while “an invisible vertical line” that ascended “from the middle of the base” to the apex symbolized their “spiritual journey” to Christ. (Without this imaginary line to Christ, the apex, men and women would be no more than beasts.)

Though Hippius adored St. Theresa, her own faith took rise not in ecstasy and visions but in a doctrine elaborated from a few mystic presuppositions and solemnized in ceremony rather than private prayer. Together with her husband and their friend Filosofov, Hippius celebrated the Eucharist in her St. Petersburg apartment in a private ritual minutely described by Professor Pachmuss: the accouterment and vestments Hippius provided for it, the tapers, silver, red satin, and gilded chalice she bought, the robes she sewed—a white cross on Filosofov’s, red buttons on the collars, with an extra one on a crimson ribbon for Merezhkovsky’s forehead—the precise order of procedure she drew up.

Private celebrations, however, were not enough. Zinaida Hippius aimed at nothing less than to arouse, in preparation for the Second Coming, “a new religious consciousness,” and thus help to establish that apocalyptic Third Testament Christianity in which all antitheses would be reconciled, and which a transformed “universal humanity” would acknowledge as “the perfect, personal faith in One Divine Personality.” To further The Cause, as she called it, she organized in 1901 a Religious-Philosophical Society which met for well over a year, until Pobedonostsev, the notorious procurator of the Holy Synod, revoked the petition he had originally granted. The Society, revived some years later when Hippius came back from France and Italy where for two years, 1906 to 1908, she propagated The Cause, reached its peak in the winter before the First World War.

The revolution of 1905, the Merezhkovskys thought, would be “a liberating storm,” sweeping away petty materialism and inaugurating “a universal union of mankind.” It was, said Hippius, “one of the elemental eruptions of the Eternal into the Temporal”; revolution and religion were “synonymous.” “But contrary to her expectations,” remarks Professor Pachmuss in splendid understatement, “the Russian intelligentsia did not succeed in establishing a religious society.” The Merezhkovskys decided the country was not yet ready for it, “Russia was politically and religiously diseased.” They went abroad.

Advertisement

The February Revolution raised hopes again. Hippius wrote manifestoes for the Socialist-Revolutionary party and declared that the idea of democracy was “the most profound, religious idea.” But with the Bolsheviks “the Kingdom of the Antichrist was established.” In 1919 the Merezhkovskys fled, first to Poland, then to Paris where, a cultural nucleus of exiled intellectuals, they remained the rest of their lives. In the Second World War, though Stalin and Hitler were “equally disgusting” to her, Hippius hoped that Hitler might crush Bolshevism. She died in 1945, four years after Merezhkovsky.

Professor Pachmuss, whose admiration of Hippius approaches worship, has been avid in her research. Her bibliography and textual references are impressive. She has interviewed or corresponded with many persons who knew Hippius, has had access to unpublished material, and seems to have read everything she ever wrote. She herself introduces her work as “a tribute to Zinaida Hippius, one of the spiritual leaders of those Russian intellectuals who actually sought a way of realizing in life their visions of a new, sublimated human society,” and concludes it as follows:

Although Hippius’ philosophy seems obsolete in view of modern existentialism, her work still has the power to stimulate the reader with a vision of eternity, of absolute reality, and, most important, all-embracing love as the basis of the Kingdom of God on earth. Hippius’ message to mankind reveals the fundamentals of Christian teaching—that love is the ultimate reality and that man must live in harmony and peace with others.

Without Zinaida Hippius the Silver Age of Russian poetry and the Russian religious renaissance would have been unthinkable. She was one of the most stimulating minds of her time, a sophisticated poet, an original religious thinker, and an inimitable literary critic. In her work the four aspects of the Russian cultural tradition—art, religion, metaphysical philosophy, and socio-political thought—receive their harmonious embodiment.

This eloquence soars high above the truth. Although Zinaida Hippius’s contribution to it was of the greatest importance, the Silver Age of Russian poetry is conceivable without her, and her literary criticism, often penetrating but limited by her doctrinaire aesthetics, has been both equaled and surpassed. (As for her “message to mankind” concerning Christian love, “There needs no ghost…come from the grave to tell us this.”) That her mind was stimulating to Russian intellectuals, who have always had a weakness for theoretical extravaganza, may very well be true, though by no means to all intellectuals: Aleksandr Blok, for one, Symbolist though he was, flew from her disputatious salon.

To Maxim Gorky, Hippius and her entourage seemed an obstruction to enlightenment. What good were people who searched for “the ‘non-existent’…beyond the bounds of the bounded,’ ” what relation could they have “to socialist art, to art that aims at educating the soul and feelings of man…to art that seeks to ennoble life?” In 1901 he called the Religious-Philosophical Society “an honorable company of holy idiots and crooks.” Nevertheless, when, in 1933, he was preparing an edition of Russian poetry, the only women poets of the twentieth century he could think of including were Hippius and Akhmatova.

While the Merezhkovskys were promoting The Cause abroad, Gorky was devoting himself to the revolutionary movement at home. He wrote prodigiously, among other things The Life of a Useless Man, a short novel, only a fragment of which could be published in Russia before 1917.1 Now it has been faithfully translated by his close friend and one-time secretary Moura Budberg. Revolutionary Russia is here obliquely seen in a provincial town through the eyes of a wretched, dull-witted government spy, Yevsey Klimkov, the “useless man” of the wholly unironic title: to decent human beings Klimkov is repellent and unnecessary, and to the police he serves, easily expendable.

Gorky draws him full length, and in damning him, damns his country. The circumstances of his life are such as traditionally would be calculated to inspire pitying affection. Orphaned in early childhood, housed and fed by his uncle, a pathetic village blacksmith, Yevsey is a puny, sluggish, sharp-nosed, round-eyed fellow, nicknamed Little Old Man, who watches others from hidden corners and seeks refuge in the village church because it is dark and quiet there, and the people who come behave meekly, not as they do outside. He likes singing in the choir when, eyes shut and his voice blending with other voices, he feels himself drifting away to a realm of peace and tenderness; and when he is maltreated by his schoolmates, he never tries to defend himself—all of which to Gorky’s mind is not the way to sainthood but to villainy.

Klimkov develops into a cringing, hypocritical sneak, who, in the most natural way in the world, falls into a job with the security police. There he is told that he “will be guarding the sacred person of the Czar” against revolutionaries and foreign agents, and although these wicked people turn out to be more attractive than any he has met before, he gives them away, without any sense of either guilt or pleasure.

Advertisement

Then news arrives that on a Sunday in St. Petersburg, an unarmed crowd with a petition to the Czar is mowed down by the police; forbidden leaflets begin to circulate; meetings are held at which revolutionary speeches are made; there is a general strike, and a demonstration provoked by the police, at which Yevsey happens to be present. He witnesses the murder of two men, one of whom is a fellow spy he knows. Why, he asks, do the police refuse to identify his body at the morgue? And is told: “We don’t need fools.” Klimkov is unexpectedly moved to a show of temper, and threatens the man who says this. But in a moment, he races off, and sure of being pursued, tries, unsuccessfully, to hang himself, then drops to the tracks in the path of an oncoming train, springs away from it in terror, and is crushed as he makes a desperate attempt to escape.

A petty coward to the end, without a trace of moral scruples, Yevsey has a vague sense, nevertheless, that things ought to be different. But how? The only lessons he has ever had amounted to this: “Do what you’re told. Keep to yourself. Never trust anybody. Remember the value of money. Make this a general rule: No one knows anything about you. And you don’t know anything about others. Happiness is ignorance.” His life is ruled by fear; and he concludes that this is the principle of all life. It explains otherwise inexplicable events: the people are poor, the Czar is rich, the people fear poverty, the Czar fears they will rob him, and so, naturally, he has them shot down when they approach his palace. Without convictions and without malice—except for a mean desire to see proud people reduced to fear when, thanks to him, they are arrested—Klimkov contributes his own nastiness to the sordid life around him, that typical Russian life which could be transformed, Gorky thought, only by a revolution.

Hippius sneered at Gorky’s lack of “culture,” “the Beautiful Lady” for whom he had “a hopeless yearning,” and who “had never reciprocated his love.” However that may be, Gorky’s love of culture was memorably expressed in his efforts to preserve art and rescue intellectuals when the hoped-for revolution came in 1917. The cultural problem was enormously difficult, how difficult one can see from Sheila Fitzpatrick’s meticulous study of the Commissariat of the Enlightenment from 1917 to 1921. Its chief, Anatoly Lunacharsky, was a Bolshevik with a difference, who had first joined the party in 1904, left it four years later on philosophic grounds, and returned in 1917, before the revolution. Together with Gorky he had once evolved a religion of “God-building” (bogostroitel’stvo), an anthropocentric theory that man himself, “raised to the height of his powers,” is God. It was on this doctrine that he broke with Lenin in 1908. His interests were philosophic, religious, and artistic. By contrast to Lenin, who was, he said, “a practical man…a real political genius,” he himself was “a philosopher…a poet of the revolution.”

He wanted the Bolsheviks to understand Marxism as a moral philosophy and recognize Marx as not merely a political thinker but a prophet in the tradition of Christ and Spinoza. Lenin thought all this “incredibly muddled, confused, and reactionary,” a kind of “scientific mysticism,” but though he once called Lunacharsky “a real charlatan,” he had sufficient respect for him to place him in charge of the country’s entire educational and artistic program, from elementary schools to universities, from the Academy of Sciences to theaters and literary organizations.

Lunacharsky had great enthusiasm and high ideals but not much ability as an organizer. “The people,” he announced in his first proclamation, “must evolve their own culture.” The Commissariat would assist, not rule, them. But the people were at each other’s throats: artists and intellectuals refused to recognize Soviet authority; proletarians demanded that bourgeois culture be totally destroyed; teachers in the capital cities went on strike and in the provinces could not understand what they were supposed to do. Meanwhile, the Commissariat proliferated into forty-two overlapping and inefficient departments, and its first, enormous budget contained a mathematical error of three million rubles. Controversy raged, intellectuals starved it was reported that teachers were reduced to begging and prostitution, and that numbers of them went mad.

Lunacharsky made compromises, now and then, in matters of administration, never in his principles. The duty of the state was to educate its people, not just provide them with technical training; to introduce them to “all human culture,” and certainly not deprive them of “the unfortunate bourgeois Beethoven, Schubert, and Tschaikovsky.” He was in consequence attacked all around, “from the left for his support of the traditional theaters, from the right for his tolerance of the left.” Bit by bit the scope of his activities was reduced; in 1922, the Commissariat was sadly disrupted when it “received only thirty-six percent of its promised allocation.” Lunacharsky, however, stayed on until 1929, when liberalism in education lost out to professionalism and technology; he refused to join those who would “trample the flower of the first hopes of the proletariat,” and resigned.

The present study, which stops with 1921—happily to be continued in a second volume—concludes, after a summary of Lunacharsky’s failures, with an estimate of his accomplishment: his Commissariat “maintained a policy of tolerance in the arts,” and in education “resisted pressure to interfere and to intimidate”—no mean triumph in the atmosphere of the times and especially in view of what was soon to follow.

Mikhail Bulgakov belonged to another generation. In 1917, he was twenty-six years old; Hippius was forty-eight, Gorky forty-nine, Lunacharsky forty-two. The White Guard was written in 1925, but its publication was stopped when the editor of the journal in which it was appearing fled abroad. The next year, at the suggestion of the Moscow Art Theater, Bulgakov made a play of it. Called Days of the Turbins, it had a great success, but in 1929 was suddenly taken off the boards, along with his other plays, and he was expelled from the Writers’ Union. He wrote Stalin, asking permission to emigrate, and Stalin, for reasons I have not seen explained, instead of granting the request, ordered the play reinstated in 1930 and is said to have gone to see it himself no less than fifteen times. After six untroubled years, Bulgakov was viciously attacked in the press, his plays were again withdrawn, he took a job as consultant and librettist for the Bolshoi Theater, and privately returned to the novel he had started and burned years earlier, the now celebrated The Master and Margarita, which was resurrected some twenty-five years after his death.

The White Guard, though not so brilliant as The Master and Margarita, is a very good novel. (A pity it could not have been more scrupulously translated!) The setting is Kiev at the end of 1918 and the beginning of 1919, with the action concentrated on three days, December 13, 14, and 15, when in the wake of the Germans’ evacuation, their puppet governor General Skuropadsky fled with his whole staff, leaving the city to the mercy of the Ukrainian Hettman Petlyura and his army of Cossacks and disaffected peasants. Bulgakov was in Kiev at the time, the family of the Turbins and even their apartment are modeled on his own, but these factual details only serve his main interest, which is, quite simply, to tell a good story, for he is not primarily a historian, nor does he want to teach, preach, or analyze. His attitude to humanity is at once sympathetic and sardonic; his gift, although more realistic here than in his other tales, runs to humor, fantasy, and the grotesque, and he is not given to abstractions. The only generalization he permits himself in this novel is the one with which he close it:

The night flowed on…. Above the bank of the Dnieper the midnight cross of St. Vladimir thrust itself above the sinful, bloodstained, snowbound earth toward the grim, black sky. From far away it looked as if the cross-piece had vanished, had merged with the upright, turning the cross into a sharp and menacing sword.

But the sword is not terrifying.[2 ] Everything passes away—suffering, pain, blood, hunger, and pestilence. The sword will pass away too, but the stars will remain when the shadows of our presence and our deeds have vanished from the earth. There is no man who does not know this. Why, then, will we not turn our eyes toward the stars? Why?

By itself this may seem weak or platitudinous, but in context, as a coda to a varied tale of bewilderment and betrayal, of loyalty, cowardice, and heroism, of pathos, comedy, and absurdity, of earthy realism and gruesome fantasy, it has a genuine and tragic ring, as if anguish, long held in check by the artist for art’s sake, now asserted its claim in a question that purports to be addressed to all men but is actually his own despairing cry; some time later it was imaginatively elaborated in the long, philosophical perspective of The Master and Margarita. And Bulgakov’s characters, amusing, delightful, dastardly or noble, are neither psychological nor ideological exhibits. Unlike Gorky’s men, who are always motivated by doctrines consciously held or painfully sought, Bulgakov’s are moved by something like “moral taste,” ingrained habits of thought, spontaneous modes of behavior.

By way of epilogue, there is a warm tribute to Bulgakov by the Soviet writer Victor Nekrasov (it first appeared in Novy Mir in 1967), who recalls how in his youth, he went countless times to see Days of the Turbins,3 how later he came upon The White Guard, and how more recently, thrilled by Bulgakov’s “resurrection,” he returned to Kiev, which was also his own native place, retraced step by step the topography of the novel, visited the apartment which the Bulgakovs had once occupied, and talked with its present inhabitants, who had known them. These are interesting biographical details, but more significant is Nekrasov’s loving appreciation of Bulgakov’s characters:

Greetings, Nikolka, old friend of my youth…. There I’ve said it. The friend of my youth, it appears, was no more and no less than a white officer-cadet. But I cannot reject him or deny him, nor his elder brother. Nor his sister, nor his brother’s friends….

For I fell in love with those people and I love them to this day. I love them for their honesty, their nobility and their bravery, and ultimately for the tragedy of their position.

In whatever political setting, then, “honesty…nobility…bravery” are still recognizable, and tragedy can elicit the sympathy even of an ideological enemy.

The cliché that Russia is a land of extremes is an excellent half-truth. Moderation, certainly, has never been a characteristic Russian virtue or its national ideal, and never less so than at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, a period very rich in art and extraordinarily violent in thought, a time of philosophic, as well as political, war. Ideologically it was a Tower of Babel in which rational debate was out of the question.

What meeting ground could there be, for example, between the symbolism and religiosity of a Hippius and the civic realism of a Gorky, when the most cherished ideals of the one were blasphemy or criminal nonsense to the other? Unwittingly, however, they did have this in common: their art at its best was independent of their theories, or only indirectly related to them. The greatness of Hippius rests on the individuality of her poems, on the intensity with which she experienced moments of dejection, not on her proclamations of universal truth; and as a literary critic her special excellence was an ability to detect and define a writer’s distinguishing quality, not the dogmatic strictures on which her judgments were based. Similarly, Gorky was at his best in portraiture and description of men he had watched, places he had seen, and at his worst in the burden of ideas with which he weighted down the men and places.

But these reflections are probably applicable to Russians by and large. They have always been better in observation, specific insights, and lyric passion than in rational theory, better in symbolic and realistic poems and novels than in theories of symbolism, realism, or any of the other doctrinal and sectarian umbrellas under which intellectuals, especially in modern times, have sought protection and companionship: Acmeism, Imaginism, Futurism, Constructivism. Tolerance, like Lunacharsky’s, or detachment, like Bulgakov’s, has been rare indeed in a period of tragic discord and usually paid for dearly. Yet the brilliant polemics of the age survive only as curiosities of intellectual history, while its art is an ageless contribution to the treasures of the world.

(The translation of “She” by Merrill Sparks is from Modern Russian Poetry: An Anthology with Verse Translations, edited by Vladimir Markov and Merrill Sparks, Bobbs-Merrill, 1967.)

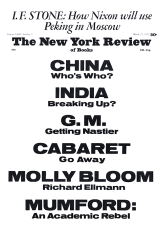

This Issue

March 23, 1972

-

1

Professor Gleb Struve has written the fullest and most accurate survey in English of Soviet Russian literature. Russian Literature under Lenin and Stalin (University of Oklahoma Press, 454 pp., $9.95), an expansion of his earlier studies, covers the period from 1917 to 1953; another volume is projected for the years following Stalin’s death. These are indispensable reference works in the field.

↩ -

2

The translation has “fearful,” which seems to me misleading.

↩ -

3

Nekrasov estimates that “not less than a million” persons have seen the play in Russia. “In the fifteen years from 1926 to 1941 the play ran for 987 performances, with an audience of at least 1,000 people each time.”

↩