In response to:

The Goat from the February 10, 1972 issue

To the Editors:

Lloyd George will always remain a subject of fierce contention. It is not surprising, therefore, that Noel Annan’s discussion of his career (NYR, February 12) deals with him in highly emotive terms (“…no principles, no scruples, and no heart”). Many of the issues which Lord Annan rightly raises are very much matters of opinion: there is little point in pursuing here such questions as the causes of Lloyd George’s fall from power after 1918 or the ethics of his notorious “fund.” I wonder, however, if I might comment on four issues of fact?

- Lord Annan denounces Lloyd George’s private life in the most severe terms—“a womanizer on a Gargantuan scale” who “used to have the typists in the lunch hour” and who, allegedly, finally estranged his own family by his sexual aberrations. Presumably there must be some evidence for these charges, beyond the level of clubland gossip. The only source referred to is the Second Earl’s extraordinary “life” of his father (1960), which is almost worthless as a historical account, even as a record of the Lloyd George household. A much more substantial source, the 2,000-odd letters between Lloyd George and his first wife between 1885 and 1936, gives a very different picture from the corrupted Bluebeard whom Lord Annan so graphically depicts. Apart from Lloyd George’s well-known relationship with Frances Stevenson, what is the evidence for this indictment?

- It is quite wrong to suggest that Lloyd George was a “pacifist” during the Boer War or at any other time. His speeches and letters at the time make it quite clear that he opposed that war on specific policy grounds—the maladroit diplomacy which had led to the war and the financial interests who were making money out of it during its course.

-

It is not correct to assert blankly that Lloyd George “hated the landed aristocracy.” His opposition was rather directed toward the maldistribution of political power which their position reflected: Lloyd George was in this sense a Populist. But, from his earliest ventures in Welsh politics in the 1880s, he admired the landed gentry in some ways, as a source of stability and of continuity in the rural scene. Also he suspected that the gentry might well prove more sympathetic toward social reform than were the “glorified grocers” of Liberalism. Hence, in part, his fruitful association with Churchill in the welfare programs of 1908-11. Neither Lloyd George, the Welsh neo-Populist, nor Churchill, the manqué aristocrat, was an orthodox Liberal.

-

Lord Annan’s categorizing of “the Liberal intellectuals” who were permanently alienated by Lloyd George’s policies at home and abroad is far too sweeping. It cannot include such pillars of Liberalism as C. P. Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian, or H.A.L. Fisher, later Warden of New College, nor C.F.G. Masterman and Seebohm Rowntree, two links between the prewar social reforms and the radical crusades of 1924 onward. Keynes himself, whose hostile essay on Lloyd George is quoted apparently with approval (“rooted in nothing”), worked most fruitfully on Lloyd George’s imaginative programs to combat recession and unemployment a few years after these cruel words were written.

Perhaps the truth is that Lloyd George alienated not so much the intellectual Liberals as the conventional and the orthodox of all parties. He was essentially a political outsider, rooted not in “nothing” but in a Welsh Populist democracy unknown either to Lord Keynes or to Lord Annan. He was, as Lord Annan observes, “a genuine radical,” essentially a critic of society and of institutions. And yet, unlike some other politicians of protest (e.g., Keir Hardie or William Jennings Bryan?) he had an artistry in the uses of power. “Who can paint the chameleon?” Wherever Lloyd George be placed in the political spectrum, it could never be as part of the Anglo-Saxon establishment. Perhaps this underlies Lord Annan’s hostility toward him.

Kenneth O. Morgan

The Queen’s College

Oxford, England

Noel Annan replies:

Clearly my tone of voice, as much as my facts, must have been wrong to have provoked Dr. Morgan’s scrupulous letter. In fact, I consider Lloyd George to be the most gifted man, and possibly the greatest, ever to have become Prime Minister in this century. Had I been then alive I hope I would have been among his supporters, and not among Asquith’s, when Asquith had been shown to be incompetent as a war leader and was ousted by Lloyd George.

No, I don’t think of him as a Bluebeard: just highly sexed. Many men in public life have behaved with far less consideration to their wives than he. On these matters there can often be no proof, and documentary evidence, if any, is usually destroyed; but would Dr. Morgan consult oral tradition?

Dr. Morgan is, however, wrong in thinking that I criticize Lloyd George out of respect for the Establishment. Quite the opposite. I criticize him, as so many of his admirers such as C. P. Scott did, for failing to re-emerge as the leader of radicalism. Perhaps, as I suggested, it could not have been otherwise: the impersonal forces of history were moving too strongly against him. But I think it remains true that, after the fall of the Coalition Government, which was a great administration, he was never trusted by the left. Nor did he perceive how important trade unions were to be in shaping radicalism.

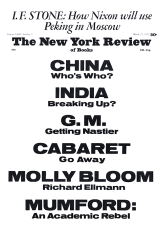

This Issue

March 23, 1972