Columbus Avenue on the Upper West Side of Manhattan is a harsh streak of downtown-rushing traffic edged by project housing, high-rise urban development apartments, Spanish grocerias, bodegas, and bars, empty lots bull-dozed for new developments, condemned storefronts, and apartments with boarded and tinned-over entrances and broken windows. To the east lies Central Park, to the west the multilingual, multicolored, slovenly vitality of Amsterdam Avenue. Columbus Avenue maintains a naked, scarred, inescapably bleak air for all the ferocity of new building in the name of urban renewal.

In September, 1970, on a corner in the 90s, two school buildings stood across from each other. One was—and still is—the sleek new brick wing of an old established boys’ preparatory school.1 The other, lodged in a (now demolished) storefront bordered by an empty lot full of broken bricks and glass, didn’t look like a school at all. Over the bright blue doorway was the sign left behind by the storefront’s occupant before the building was condemned: ELIZABETH CLEANERS. Across the street a huge crane hauled building materials to the top of a half-finished high-rise. In the store-fronts next door and down the block were an assortment of grassroots community projects: a cooperative fruit store, a day-care center, a council of the dispossessed tenants squatting in the condemned buildings, a free coffee shop, a neighborhood candy store. Inside the Elizabeth Cleaners a tuition-free, alternate high school was beginning to hold classes.

In June, 1970, after checking their plans with Operation Move-In, the local squatters organization, about half a dozen parents, two prospective teachers, and about ten students broke open the entrance of the abandoned cleaners and took possession. The group had been meeting since early February, with fluctuating membership and erratic levels of hopefulness, trying to devise some alternative to the experiences the students were having in various schools around the city. The common linkage among all the families was the fact that the students, whether they were attending conventional private schools, New York City public schools, or “liberal-progressive” private schools, felt completely disaffected from their education. Some were simply sitting out the time of forced servitude in sullen misery; others were listed in their schools as underachievers, disturbers of the peace, problem students; others were frequent truants. For all—and these were bright, articulate adolescents—boredom and anxiety were the routine feelings in the classroom.

Some of the parents actively shared their discontent; others simply felt that they wouldn’t, or couldn’t, force their children to go to schools they hated. The group was amorphous in many ways but essentially white, middle-class, professional (most of the mothers work), and politically liberal. For most of them, breaking into and entering a storefront was a previously unthinkable act; and the idea of a school controlled by students—with no bureaucracy, no accreditation, no financing, and no guarantee of permanence—was a concept most of them would have difficulty grasping for some time.

Throughout the summer of 1970 a few students practically lived in the storefront, which had been cleaned up and repaired by them with parents and interested teachers assisting, and which over successive weeks accumulated donations of folding chairs, a few tables, some mattresses, posters, the beginnings of a paperback library, a secondhand refrigerator. The summer was spent in almost fruitless attempts to recruit students from other ethnic backgrounds represented on the West Side—largely black and Puerto Rican. In fact, the school is open to any student of twelve to seventeen who wants to go there. For a while it was hoped that active recruitment could make it educationally relevant to the needs of other than middle-class students; as yet this hope has not materialized. Lack of formal accreditation is a major reason why.2

Also during the summer students tried to raise money, through contributions, through the sale of food and crafts at block parties, and through letters to foundations. The decision was made to hire two paid, full-time teachers, a man and a woman, at $100 a week, and to seek volunteer teachers for special subjects who would donate their time. The students interviewed about forty prospective teachers, who were attracted through fliers, through an advertisement in The Rat, and by word of mouth. They decided on David Nasaw and Elaine Louie (who was later replaced by Jane Kinzler), and began planning a curriculum. They also became involved, as did some parents, in the crises and day-to-day life of the squatters group and the block. Some helped new squatters take possession of apartments. Some worked in the day-care center. By September, though everyone concerned still had a sense of the fragility of the operation, the school was undeniably in existence as a group of people and a place.

In the two years that have passed the school has moved three times. The first move was to a storefront a block or two away which it shared with a community youth center. Over the summer the building was left unlocked and “trashed,” and the city took possession again, tinned it up and boarded it over. The students then decided to look further afield and managed temporarily to rent a couple of rooms in the Mercer Arts Center, near Washington Square. For many of the original founders, leaving the Upper West Side was a major decision, and for some the sight of the razed block where their first storefront had stood still brings a pang. The school is now in a loft on lower Broadway. Lisa Mamis, its first “graduate,” will enter the State University at Purchase next September.

Advertisement

* * *

The following is an imaginary conversation—imaginary in that it has taken place in bits and pieces with a number of people rather than as the dialogue that follows. I have named the composite questioner Zelda.

Zelda: So your children are at a Summerhill kind of school now?

Adrienne: Well, that depends on how you mean it. It’s not a boarding school, it’s in the city. And there is no A.S. Neill character. It’s an alternate high school controlled by the students.

Z: Who is the headmaster?

A: There is no administration. There are just students and teachers and, off to the side, parents. The kids interview the teachers and make arrangements for classes with the ones they like. The teachers offer classes whose materials are agreed upon between them and the students. They also work with the kids in maintaining the storefront the school is in, relating to the community, raising money. The parents make contributions when and if they can to help pay teachers’ salaries and maintain the school. One parent acts as a kind of treasurer. The school is nominally tuition-free.

Z: How did you get recognized by the Board of Education?

A: We’re not. As far as the law is concerned, our children are dropouts. We have no charter, no accreditation.

Z (taking all this in by degrees): How do you decide about admission?

A: Anyone can come. We have an age qualification of twelve to seventeen, but even that’s not rigid. New students have been joining the school all year.

Z: Don’t you get a lot of…misfits, disturbed people, problem kids?

A: I suppose by the definition of the conventional education any or all of our children would be misfits. Some were in fact academically “successful” in the old schools but bored and miserable. Some were simply not going to class, not in any way engaged with the process of education as those schools defined it. Some were thrown out of their old schools, others refused to go back. All of them, I guess, would be labeled “problem students” in the dossiers of both private and public schools of the establishment.

I happen to feel that it’s a rather honorable and hopeful thing to be a “misfit” in this kind of educational system. And that people labeled as “problems” by this society are often people who are responding with healthy revulsion to a process which seems to have no meaning for them and is trying to package them for sale in a market place. They may show this revulsion in self-destructive ways—shooting up, for example. The students in this school seem to me to be people who have reacted by trying to create something new, something that has never existed before. That strikes me as a very healthy kind of behavior, even when they make mistakes, as they must, or get confused by the very newness of the process.

Z: But what about college? Surely some of these kids are going to regret it later if they can’t go further in their education. They may be turned off from the classroom now, but later see that it has something to offer them.

A: That was one of the first questions that came up at our earliest meetings. From kids as well as parents. But there is a growing sense that colleges will be—are already—interested in students who have not gone through the normal academic process. The alternate school, after all, is a spreading phenomenon, attracting some of the most alive, aware young people—both as students and teachers. Alternate colleges are also appearing. And interestingly you see the student who has gone dutifully and successfully through school dropping out of college when he gets there.

We do assume that if you really want to, it’s possible to make up the usual high-school curriculum in much less time, in order to get an equivalency certificate or pass Regents’ exams. If that’s important to a student, he or she would have that option. But we are clearly living through the death throes of the old educational organism—which isn’t an organism any more but a machine that is destroying itself, and destroying people as well.

Advertisement

Z: But what do you see in the future for your children? Suppose they can’t get into a good college?

A: I’m not sure we know what a “good” college means. In all sorts of institutions you find good teachers, students who are teaching each other. It’s like talking about a “good” city. The old academic degree-mill, however prestigious, isn’t a scene I feel to be necessary for the development of the mind. Finally, I expect that students from alternate schools will be demanding a more human experience in any further education they may seek out—that that will seem more important than the number of cyclotrons the university has, or how many Pulitzer Prize winners are on the faculty. They will be less interested in degrees than in the process of experiencing and knowing and giving form to their experience.

I don’t find that I can see into the future for my children any more than I can for myself. We live at a moment of intense uncertainty, none of us can really say that we know where or how we’ll be living in five, ten, or twenty years. When we broke into the storefront on Columbus Avenue and some of us spent the night squatting there, it was for a lot of us an utterly new kind of act, a new way of perceiving ourselves as parents, as citizens, as good middle-class people. And all of us have been going through similar unexpected experiences for a number of years now. It’s part of being alive today. We, the parents, are having an education in uncertainty which none of our previous schooling gave us, because it was always based on the notion that there were certain paths you could follow to reach certain prescribed goals. Even if you chose not to follow them they were there.

Z: I’m going to say something rather blunt. You yourself came out of that middle-class, academic background, took an A.B. degree at a good college, married an academic—isn’t it possible that you are just projecting onto your children your own reaction against all that academic training? Maybe you are just living out your own unlived life through your children—giving them some kind of “freedom” you feel you missed, reacting against the academy, through them.

A: That would be very sad, if true. However, I didn’t press my children to leave the conventional private school they were in and become dropouts or experimenters. For over a year I’d been hearing disturbing reports from them about their school and had actually not wanted to believe them. I only gradually relinquished my trust in that school after repeated interviews with directors and teachers, in which their shallowness of purpose and their fear and hostility toward young people became increasingly evident. The children were tremendously aware of the injustice and hypocrisy—and in many cases, hysteria—that were endemic in their private school. It took me much longer to see it, because I wanted to believe that they were safely in a liberal, enlightened, child-centered place and that I could stop worrying about schools and think about other things.

When we started meeting to talk about setting up a free school, I felt a deep ambivalence. In theory I felt Paul Goodman, Neill, Dennison were right, accorded with my own instincts about human needs and how people develop. But I also feared for my own children—fears you’ve been raising and others: Will they have the option of going to college? Will they be challenged enough? Will they really know how to organize their time? Isn’t this an extremely risky and fluid situation to let them loose in? But it was becoming clear that among the established schools in New York there was no real range of choice. The students at X School might wear blazers and those at Y School blue jeans, but certain fundamental attitudes toward adolescents and toward learning prevailed throughout. While the public high schools were either essentially custodial institutions or stressed “achievement” in terms of marks, IQ, all the things I felt were destructive of real learning and understanding. Also, I saw the students slowly beginning to coalesce into a group, with certain ideas about how the school was to be run and what they hoped it could be.

I suppose you tend to be more cautious, less radical, for your children than you would be for yourself. Until the moment when you realize that what looks like the “safe” thing for them is really a sterility, even a threat to their humanity. I would have taken a similar leap for myself with fewer qualms—because, as I say, I’d become convinced that the old schooling is deadening to the imagination, to the growth of the self, that it promotes cynicism and passivity. But it was a much bigger leap to assent to for my children. Their own inclinations were very obvious. But I also felt how young they were to have to make such choices.

Z: You didn’t feel at any point, this is a cop-out, they and I ought to stay and try to effect changes within the institutions that now exist?

A: Many of the parents had been fighting in PTAs and parents’ meetings for years. And some of the kids had tried for change in their schools. No, I didn’t feel it could be a cop-out for any of us: it was taking a very hard path, a path of tremendous personal responsibility, involving many kinds of stress and anxiety. To change the school my children were in would have necessitated bringing about profound changes in the values and aspirations of trustees and influential parents and of administrators who were determined to keep dissenting parents ignorant of how decisions were made and even what decisions were being made. That kind of struggle might seem worthwhile if you had years ahead of you. But our children had only a few more years ahead of them and as mine kept saying to me: School is my daily life, it takes up most of my week, and it shouldn’t be necessary for one’s daily life to be so oppressive.

Z: And are they—and you—satisfied with what you have now?

A: Look, this is no dream-school, no perfect solution. It’s a small, loosely knit, struggling group of people in an unheated, improvised storefront, learning about themselves, each other, community relations, plumbing, politics, how and why structures develop or crumble—all this along with more academic-sounding “subjects” like Cuba or American history or creative writing or psychology. I can say this: my children go to school this year as to a place where they want to be. They feel deeply involved even when they don’t like what’s going on. They suffer the strains of any small community, and the strains of living in an ethnically divided, politically volatile neighborhood. They’re learning to improvise, to do things for themselves, to make mistakes and survive them.

And I’ve been learning that a lot of my anxieties were groundless. The kind of constant jailerlike supervision provided by the average high school is utterly unnecessary, the checking in and out. Also, I’d feared that children who had never known this kind of educational freedom would find it paralyzing, even though it was what they’d asked for. Well, this is almost the end of the first year, and despite times when the children and I have feared the school was crumbling through lack of direction or discipline, there has been a real will to keep it going, to endure conflict, to go on. There is often confusion and lack of focus, but I’ve seen no signs of paralysis.

I think anyone—student, teacher, or parent—intending to engage in this kind of education should know from the start that it won’t be some kind of idyllic situation, free people engaged in free learning. Nobody is free in America today, and we bring to our projects a lot of old fears and habits learned in American society. It’s a far from simple process.

Z: You mentioned some of the things they study—do they study math and science?

A: There was a math class but I gather it’s recently turned into an oceanography class. We haven’t yet had enough money for scientific equipment, though I believe if a student came in wanting to study, say, chemistry, a way would be found.

Z: So none of the students will have the background to specialize in any science?

A: I think any student with a genuine interest in science can make up high-school math very quickly.

Z: But how will they even find out that science is what might interest them?

A: It’s hard to avoid hearing about science, if you’re awake and alive in New York City. I do think that for a lot of kids, math represents the paradigm of the kind of exam passing, test taking pressure that has been so destructive to them in other schools. Also of the value-free, neutral, abstract kind of science which many young people in colleges, also, are rejecting now. It may not be a fair vision of mathematics, but it is a fair comment on how math has been taught.

Z: But listen. You hope for some kind of social revolution in this country, don’t you? Suppose you have a generation of young people who are illiterate in science and technology? Who will take care of the sick, who will be the new urban engineers, who will help save the environment?

A: We had the Sputnik generation of scientists, who were fostered and encouraged in the cold war, and they cannot or will not do these things adequately or even decently. I’ve come to feel that a new kind of scientist will be needed for the next century, if man survives. Someone more complex, someone who perhaps hasn’t been channeled into science at an early age. He will need a lot of flexibility, resiliency, independence of spirit, he’ll need to be able to deal with things that don’t fit into any intellectual categories we’ve had since Aristotle. More than anything he’ll need—as we all will—a humane responsiveness to other humans. It’s true, we used to think training in the humanities could give us that kind of person, but it hasn’t—people brilliantly trained in the classics can be perfectly indifferent to the degradation of living people around them. And the scientific mind—we used to identify that with curiosity, daring, Prometheus bringing fire of the gods to man. But we’ve seen this mind to be also rigid, unimaginative, fearful of the emotions, indifferent to man.

The thing I really hope for in my children’s education is that they should experience themselves as subjects, instead of being simply acted on as objects. The old schooling talks about the former, but its methods result in the latter.

I’m not saying that the alternate high school has any formula for providing this, but from my children’s experience this year, and my own, I’d say that it’s a more likely environment for it than the old, categorical, one-way-street education.

Z: You said before you’d had grave qualms about taking this step, or letting your children take it. What makes you so sure that you did the right thing?

A: Seeing my children interested in life, in good spirits, taking on very tough problems and dealing with them pretty well, seeing them excited by ideas and people they encounter in school. But above all, seeing that they want it to continue, that for all the difficulties it seems worthwhile to them, a daily life they want to live.

Z: And for you as a parent? Has the school affected your life?

A: Indirectly, very much so. It has forced me to think a great deal about the ways adults oppress children, the stereotypes we draw of adolescents and their needs; it has helped me accept far more my children’s increasing maturity, their right to make their own mistakes. When they’ve felt discouraged and depressed by the problems of a wholly new situation, I’ve felt depressed and discouraged, too. I’ve wondered whether we as adults were not failing in our responsibility to organize and direct our children’s education for them. On the other hand, it’s given me a kind of long-range trust in what they have chosen. The problems of starting the school have certainly made me less romantic about the process of creating counter-institutions in this country to replace the ones that are failing us. As I say, it’s made me realize how much of the influence of those failed institutions we carry with us when we set out to create anything new.

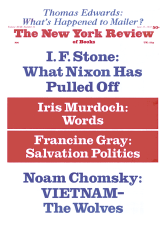

This Issue

June 15, 1972

-

1

Part of the funds for this private school’s new wing came from public appropriations for urban renewal. The community was to have shared in swimming facilities provided by the new building. Now, two years later, the community has still not been given access to the pool, and pressure is being placed on the school to open it to neighborhood youth.

↩ -

2

Black and Puerto Rican students and their parents justifiably question the value for them of a school which would place them in the jeopardy of being classified as “dropouts” and which could prove simply another roadblock to breaking the cycle of their minority status. New York City schools are hardly an alternative; the minority student who survives the brutalization of the system is still liable for “tracking” into vocational training, and if he survives even this and is admitted to the City University as an “Open Admissions” or SEEK student he has to struggle to repair the damages inflicted by twelve years of schooling. Black students on scholarship in private schools often feel that these schools want to turn them into whites, are insensitive to their needs, and politically conservative. However, it is fully understandable that, given the system of advancement via credentials, minority students and parents are mistrustful of educational experimentation.

↩