In response to:

Deep Language from the February 8, 1973 issue

To the Editors:

George Lakoff’s response [NYR, February 8] to John Searle’s article on linguistics [NYR, June 29, 1972] is largely a criticism of views he attributes to me. In fact, there is little resemblance between my views and what he believes them to be. More important, Lakoff presents a very confused picture of the issues that have been under discussion in the work to which he refers and an entirely fanciful account of the interests and concerns of various individuals and groups working in the field. I cannot take the space to disentangle each confusion and correct every misrepresentation, but a few examples may suffice to illustrate the intellectual level of Lakoff’s attempt to correct “nonspecialist articles about linguists.”

Lakoff’s first and major example is what he calls “the behaviorist vs. rationalist dispute.” He states that I have “characterized structural linguistics as being fundamentally behavioristic” and “necessarily tied to behaviorism,” and that my argument for rationalism “is based on the existence of linguistic universals.” But structuralist theories have “incorporated claims for extremely complex and sophisticated linguistic universals” and these, Lakoff argues, are “more than complex enough” to refute behaviorism.

The relevant background facts are, briefly, as follows. I and others have suggested that it is useful to distinguish two approaches to the study of language acquisition, call them E and R, where E incorporates (inter alia) the variety of proposals within structural linguistics and behaviorist psychology that bear on the issue, and R differs in fundamental respects. We have also argued that E and R express certain leading ideas of empiricism and rationalism, respectively, and that the results of transformational generative grammar support R over any variety of E. I will not try to explain or defend these views here (see Alan Gewirth, NYR, February 22, for some illuminating comment). Details are given in publications that Searle cites. I am concerned here merely with the logic of the argument.

Notice first that the dispute is not between rationalism and behaviorism, but between R and E. Lakoff is, I believe, correct in stating that the universals postulated in one subvariety of E (structural linguistics) are “complex enough” to refute the claims of another subvariety (behaviorism). True or false, the matter has no bearing on the question at issue, namely, whether E or R is correct. Since Lakoff gives no citations, I cannot comment on his belief that I have characterized structural linguistics as “fundamentally behavioristic,” except to say that I hold no such view and have not “conveyed the impression” (as he claims) that there is a necessary connection between the two. I have clearly differentiated the two schools in discussing this issue (see, e.g., Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, 1965, p. 51f). Lakoff asserts that my “portrayal of structural linguistics” is “inaccurate,” but he seems to be quite unaware of what this portrayal actually is (cf. ibid.; Language and Mind, 1968, chapter 1; Current Issues in Linguistic Theory, 1964). Perhaps Lakoff is misled by the fact that I and others have subsumed structural linguistic and behaviorist approaches along with others under E, while making it quite clear that this general approach incorporates many diverse and sometimes conflicting views.

Lakoff’s statement that the argument against behaviorism “is based on the existence of linguistic universals” is completely wrong. Behaviorist approaches, obviously, imply the existence of linguistic universals. What is at issue is not whether there are linguistic universals but rather what they are—specifically, whether they bear on the choice between E and R. If one wanted to show that the results of structural linguistics refute behaviorism, he would consider the most “complex and sophisticated” structures investigated in the former and argue that these violate behaviorist universals, i.e., cannot be attained by mechanisms postulated by behaviorists. The natural candidate would be the class of structures given by Harris’s morpheme-to-utterance procedures (Methods of Structural Linguistics 1951). However, in a further misrepresentation, Lakoff describes Harris (quite falsely) as “an extreme case of a behavioristically oriented taxonomist,” thus neatly closing off the best method for establishing his irrelevant claim. At this point, confusion is complete.

Lakoff next turns to my “account of so-called Cartesian linguistics.” He claims that this account is refuted by work of Robin Lakoff’s which showed that “what Chomsky called Cartesian linguistics had nothing whatever to do with Descartes, but came directly from an earlier Spanish tradition”; and specifically, that the Grammaire générale et raisonnée (GGR) of Port-Royal derives from the work of Sanctius. But Robin Lakoff, in the 1969 review of the GGR that George Lakoff cites, reaches a very different conclusion. She concludes that “although Cartesian philosophy was undoubtedly an influence on L & A [Lancelot and Arnauld] in their writing of the GGR, as well as in their coming to hold the ideas of language exemplified in the GGR, the actual form of their theory originated in other sources…[viz., Sanctius]…. Descartes, I would say, created in L & A a favorable mental climate for them to accept these linguistic ideas.”

Furthermore, both Lakoffs fail to mention that in introducing the GGR in my Cartesian Linguistics (1966, note 67) I stated: “Apart from its Cartesian origins, the Port-Royal theory of language…can be traced to scholastic and renaissance grammar; in particular, to the theory of ellipsis and ‘ideal types’ that reached its fullest development in Sanctius’s Minerva” (see also p. 50, where the essential point is reiterated, and note 101, where still earlier antecedents are discussed). Thus George Lakoff’s assertions not only misrepresent my account, but are also strikingly inconsistent with Robin Lakoff’s position (which he claims to be reproducing); the latter, in the matter at hand, is close to that of Cartesian Linguistics, as the quotes indicate.

Confusing the matter further, George Lakoff asserts that I base my claim “that Cartesian rationalism gave birth to a linguistic theory like transformational grammar in its essential respects” on the GGR. This is, again, a serious misrepresentation. In the first place, as just noted, I did not describe the GGR as simply a product of Cartesian rationalism (though others have). Secondly, Lakoff has misstated the thesis of Cartesian Linguistics; cf. pp. 1-3 and note 3, where I emphasize that I am reviewing varied and divergent traditions including some “antagonistic to Cartesian doctrine,” and that I was explicitly not concerned “with the transmission of certain ideas and doctrines, but with their content and, ultimately, their contemporary significance.” Furthermore, the thesis that Lakoff misstates was not based on the GGR but on a grammatical tradition that develops from it (and other quite separate developments).

In the sole reference that Lakoff cites in this connection, namely Robin Lakoff’s review, the still stronger claim is made that one may “speak of a Cartesian school, with the GGR as a seminal influence.” Compare this with George Lakoff’s rendition: the school in question “had nothing whatever to do with Descartes.” Actually my position is intermediate between those expressed by the two Lakoffs, on this issue: the tradition developing from the GGR did have something to do with Descartes, but it was not, in my view, “a Cartesian school.” Rather, leading figures were directly influenced by scholastic and renaissance grammar, as they themselves indicate “with abundant references” (see Cartesian Linguistics, p. 50). The relevant point here is that George Lakoff has thoroughly misunderstood the references he cites, and his account of the issues is confused beyond repair.

There are differences between Robin Lakoff’s interpretation of the real issues and my own; see Harry Bracken, “Chomsky’s Cartesianism,” Language Sciences, October, 1972, for an informed and I believe accurate account. But these differences are far from what George Lakoff presents in his hopelessly garbled version.

Still more surprising is Lakoff’s reference to the “devastating critiques” of my “treatment of…Locke.” Lakoff overlooks the fact that for there to be a devastating critique of X, it is necessary to X to exist. The condition is not satisfied, in this case. I have written virtually nothing on Locke, and my few marginal comments have been subjected to no “devastating critiques,” which is not surprising, given their character.

When Lakoff turns to what he takes to be my views on language, his comments are at about the same level of accuracy. Thus he claims that it is necessary to reject certain of my “fundamental assumptions,” of which the first is “that syntax is independent of human thought and reasoning.” The reader who searches for some expression of this “fundamental assumption” will, no doubt, be surprised to discover what I have actually written about the matter. My position has always been that: “A decision as to the boundary separating syntax and semantics (if there is one) is not a prerequisite for theoretical and descriptive study of syntactic and semantic rules. On the contrary, the problem of delimitation will clearly remain open until these fields are much better understood than they are today. Exactly the same can be said about the boundary separating semantic systems from systems of knowledge and belief. That these seem to interpenetrate in obscure ways has long been noted….” (Aspects, p. 159); “…it is not entirely obvious whether or where one can draw a natural bound between grammar and ‘logical grammar,’ in the sense of Wittgenstein and the Oxford philosophers….” (Current Issues in Linguistic Theory, 1964, p. 51); “there are striking correspondences between the structures and elements that are discovered in formal, grammatical analysis and specific semantic functions…. These correspondences should be studied in some more general theory of language that will include a theory of linguistic form and a theory of the use of language as subparts…. An investigation of the semantic function of level structure, as suggested briefly in section 8, might be a reasonable step toward a theory of the interconnections between syntax and semantics….” (Syntactic Structures, 1957, p. 101f.). Again, there are real issues in this area, but one would not be able to guess what they are from Lakoff’s account.

The preceding is a limited but fair sample. Lakoff seems to have virtually no comprehension of the work he is discussing. In fact, there are certain respects in which his position diverges from mine, and it would be interesting to pursue these differences (for my own views of the matter, see my Studies on Semantics in Generative Grammar, 1972, particularly chapter 3). It is unfortunate that instead of making the effort to discover what the issues are and then trying to deal with them, Lakoff has—in the guise of an expert response to a “nonspecialist article”—discussed views that do not exist on issues that have not been raised, confused beyond recognition the issues that have been raised, and severely distorted the contents of virtually every source he cites.

Noam Chomsky

Cambridge, Massachusetts

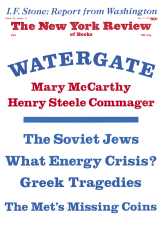

This Issue

July 19, 1973