—Lisbon

…I have heard many complaints of abuses in cases of arrests, in the ordinary treatment of prisoners, and of conditions in the overcrowded prisons. Such complaints prompt the recollection that it was after all the older generation that suffered the abuses of the police under the former regime and that the young really do not know the moral, psychological, and social implications of persecution.

Take one proven fact. There are several men, who happen to be rich bankers, who have been arrested by unauthorized groups of marines and soldiers in uniform or kept in jail in spite of orders for their release. In many cases they have been rearrested, the record being now the case of a bank tycoon, the Count of Caria, who has been arrested and re-arrested five times.

Well, I remember my own shattering experience of undetermined and arbitrary imprisonment and torture and isolation under the former regime. Such a man is no longer just a rich man. He is likely to be a poor individual, deprived of the right to sleep even when he goes home to his family without knowing when he will next return to prison.

And then it is also the young, and often the very young, who point the finger and mock at the children of the former state police officers and make their life a misery. All in all, revolutions might be justified and necessary in social history, but when they are happening they can be ugly and brutal. And not all violence is marked by blood.

I have complained about this to many veteran freedom fighters whom I know well and who now hold positions of power. I have also told them that as disturbing as the events is the fact that again in Portugal no one dares or can bring them openly into the media.

I have the impression that all this is happening because the old in Portugal have their attention turned into the multiple and urgent tasks of steering the country from dictatorship into democracy. But since the young know of both only through what they read in books, I wonder whether their experience qualifies them to arrest people.

I, for one, can tell them that they are inflicting on others many of the abuses the previous regime inflicted on me and on many men of my generation. It was so bad that I lost the taste for revenge.

After the April 23 election, it is expected that conditions in Portugal will settle to allow a solution of the problems of the estimated 1,500 prisoners now held in Portuguese jails.

These are divided into the agents of the former security police PIDEDGF, and other paramilitary institutions such as the Portuguese Legion and the APN, a former regime’s single party. Among this group of prisoners are many with heavy responsibilities, but others less incriminated.

Another group of prisoners is made up of army officers and civilians alleged to be involved in plots in September last year and March this year as well as in the activities of a liberation army allegedly based in Spain.

The Portuguese Minister of Justice, Dr. Salgade Zenha, himself a well-known writer on civil rights, is not alone in complaining that too many people in Portugal are now imprisoned who do not benefit from the ordinary judicial system. He is one of the main forces pleading for higher priority to be given to human rights.

Other leading figures in the regime, namely Brigadier Otelo de Carvalho, have said that many of the prisoners should be allowed to emigrate to Latin-American countries.

But there can be no doubt that the question of political prisoners in Portugal is both a moral and political problem that makes the new regime increasingly vulnerable to international criticism and widespread resentment in Portugal.

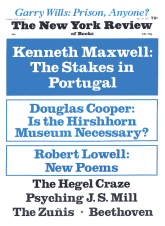

This Issue

May 29, 1975