In response to:

The Ultra Ultra Secret from the February 19, 1976 issue

To the Editors:

As the historian who lent his name to a laudatory dust-jacket evaluation of Anthony Cave Brown’s Bodyguard of Lies, I take exception to Professor H. R. Trevor-Roper’s criticism of the book in your pages [NYR, February 19]. Having written seven books on World War II in Europe, including three of the US Army’s official histories, I consider that I have sufficient qualifications to warrant my assessment of the historical value of the book: “This secret history of D-Day is the most important work on World War II in a quarter of a century, a triumph of revelation and presentation.” I stand by those words.

Professor Trevor-Roper errs at the start in calling the book “a general history of Anglo-American intelligence” during World War II. Any reader should be able to discern that it is instead a history of strategy and stratagem leading up to D-Day, albeit strategy and stratagem in which intelligence played a major role. If that complex subject was to be adequately handled, the book had to be of considerable size, which even if it troubles your reviewer, seems to have been of no concern to the American book-buying public.

Nor did I as a reader have any difficulty—as the reviewer says he did—in discerning from my copy of the book “the real structure of British intelligence” or, for that matter, the German Abwehr. My copy also gave no impression that the author thinks MI-6 controlled all British intelligence.

From personal knowledge, I can assure the reviewer that Mr. Cave Brown did not obtain his materials “indirectly.” Much of the material came from the US National Archives, released after considerable effort by the author under the Freedom of Information Act, and much from personal interviews, including detailed interviews with F. W. Winterbotham, author of The Ultra Secret. Indeed, it was Mr. Cave Brown who persuaded Mr. Winterbotham to write his memoirs, helped him to do so, provided some of the material, and arranged for a publisher. Although the head of MI-6, Sir Stewart Menzies, did indeed talk openly and candidly with the author on several occasions, the true circumstances of those interviews bear no resemblance to the reviewer’s misguided attempt to reconstruct them.

As to Professor Trevor-Roper’s doubt that CICERO, the spy in Ankara, was under British control, Mr. Cave Brown reflected his caution on that subject on the last page of the CICERO chapter. Since publication, however, he has uncovered documentation in the National Archives that leaves no doubt as to the validity of his thesis.

To go on at length about the other primarily trivial matters which Professor Trevor-Roper raises would be to credit a long-discredited reviewer’s method of faulting an important work by quibbling over details. It is of no real consequence, for example, whether a man was or was not a flyfisherman, except that either way he should not lie to Who’s Who. Nor am I as an American reader particularly interested in the campaign apparently underway in some British intelligence circles to denigrate retroactively the accomplishments of Sir Stewart Menzies, for I have been assured by responsible former American officials that Sir Stewart’s contributions were of the first importance. Do I not detect also a trace of that time-worn academic contention that the only true history has to be dull history?

Charles B. MacDonald

Arlington, Virginia

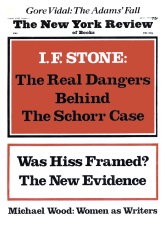

This Issue

April 1, 1976