In response to:

Ancient Incas and Modern Revolution from the March 18, 1976 issue

To the Editors:

The house copy of The New York Review of Books arrives by slowboat and train here to La Oroya in the Central Andes of Peru. So I was very happy a friend clipped the article “Ancient Incas and Modern Revolution” by Robert M. Adams and sent it to us airmail.

Upon first and second reading I kept saying to myself: “Say it isn’t so!” Unfortunately, the tone and character of Adams’s description of Peru is quite faithful to the realities as I know them after almost three years in pastoral work. The article is a little short on hard facts and data; perhaps it is not good reporting, but it does give a good journalistic overview of the situation.

If anything, Adams is too optimistic and sanguine about the agrarian reform and the new agrarian cooperatives. Numero Uno of these cooperatives is centered at Pachacaya, some thirty-five miles below La Oroya. Bureaucratic bungling and insensitivity to the cultural patterns of the people lead to a total lack of concrete positive programs for the campesinos themselves. This very day we visited a very remote rural village in these “high, sparse, cruel, and cold” Andes. Two truckloads of government people preceded us through mud and snow to conduct a three-day seminar for the villagers to “deepen the revolutionary process.” It was all well planned and organized; typically, it was all talk. When only a few people arrived for the first meeting of the seminar, the government people simply quit; they packed up their gear and returned to their warm, comfortable offices to make out their reports. Life in the pueblo goes on as before: hard, cruel, poor.

This village is part of the best and largest rural cooperative in Peru. Of course, there is no electricity, no drinking water, no toilet facilities of any kind. The large health clinic has no doctors and only a local male nurse to care for the people. In a second village the people told us that the local community had just completed a new contract with several distant villages which produce ordinary agricultural products. (Where we were it is so high the people have only flocks of sheep and llamas and a few alpacas and cows.) By this contract they would exchange live animals (meat and skins) for potatoes, beans, and various forms of wheat, rye and barley flour. In other words, after some six years of the agrarian reform, the villagers find it necessary to revert to a marginal bartering economy: they still find it impossible to survive in a market economy where money is the means of exchange.

Here in La Oroya itself CENTROMINPERU is the new government company which replaced Cerro de Pasco Corporation of New Jersey on January 1, 1974. Since then, the mining business has come upon hard times. Mostly, the whole international market for copper and other minerals has closed shop. CENTROMIN-PERU has been forced to issue public denials against the rumors that whole mining camps will be closed down.

That Adams could write a rather comprehensive report on modern Peru and include nothing about the Catholic Church is not a criticism of the report but another sad commentary of the Peruvian reality. The leaders of the Church make very balanced but very safe political and economic statements, but the Church is not very evidently active or effective in giving direction, vitality or a sense of real values to the Peruvian people as a whole….

Ernest W. Ranly

La Oroya, Peru

Robert Adams replies:

Mr. Donnelly rebukes my confidence in saying what “the real problems” of Peru are; and, on looking the article over, I’m afraid he’s right here—some of my judgments came out sounding too pat and positive for what was, after all, intended only as a travel sketch. I’m happy to have a chance to reemphasize my negatives.

To begin with a disclaimer, I don’t for a minute accept the charge that the “Brazilian model” or any other specific model of development was what I had in mind for Peru. The problem as I saw it (and I was more concerned with defining dilemmas than with offering models to solve them) was poverty. Poverty is too few goods for too many people. If one isn’t to diminish the number of people, one has to increase the quantity of goods and distribute them more equitably. There is no question that the present Peruvian regime is pursuing both these latter alternatives, as I categorically said. But there’s no question, either, that the nation needs more production to raise the still low standard of living, and that the distributive social reforms have been relatively shallow in their effects. For Peru to pull herself up by her bootstraps will be a hideously long and painful process, especially when social planning must proceed under the handicap of such immediate pressures as I described.

One alternative is outside aid. Obviously if such aid, whatever its source (and there are several), is exploitative or crippling of Peru’s interests, it shouldn’t be accepted. But First-World money is in fact being solicited and accepted by modern Peru—the question isn’t whether, but how much and on what terms. Colombia and Bolivia, both signatories to the Andean Investment Code and bound by its terms, are getting great quantities of such money. If Peru is getting less, it may well be because she’s done something less to encourage it, or more to discourage it. I’m not recommending Colombia and Bolivia as models, any more than Brazil, just pointing up dilemmas that the regime faces. The price of foreign investment may be exorbitant, though it can be (and is being) bargained over; but the price of no foreign investment may be exorbitant too—and it’s harder to extenuate.

Thus I do think two elements of a solution for Peru, as for most underdeveloped countries, are (1) to develop the productive plant fast, while mortgaging the national future as little as possible; and (2) to iron out the fearful inequalities of distribution by spreading the benefits around. In a sense Mr. Donnelly is right, this is a Western-capitalist prescription. But it’s also an Eastern-socialist prescription. Doesn’t the Soviet Union believe in expanding its productive plant and raising the living standard? Isn’t that what China is trying to do? Many of the means are different, the general objective is the same. And must be: there simply isn’t any way to support mass populations without some mass-production techniques. Peru is making a very special conscious effort to balance costs against benefits of development. My final sentence emphasized the narrow range and great difficulty of the decisions confronting modern social engineers, as contrasted with the unlimited freedom enjoyed by the Inca. The more tricks and traps turn out to be attached to foreign aid (and US aid has in the past been booby-trapped with far too many sneaky-Pete devices), the more that judgment, at least, is confirmed.

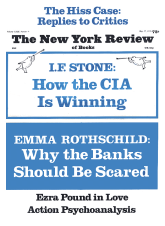

This Issue

May 27, 1976