The statement that clothing is a language, though occasionally made with the air of a man finding a flying saucer in his Queens backyard, is not new. Balzac, in Une Fille d’Eve (1839), observed that for a woman dress is “une manifestation constante de la pensée intime, un langage, un symbole.” More recently Roland Barthes, in “The Diseases of Costume,”1 speaks of theatrical dress as a kind of writing, of which the basic element is the sign. As far as I can discover, however, neither the structuralists nor other, earlier theorists have gone on to remark that the language of dress, like other languages, has a vocabulary and a grammar. In different places different “languages” are spoken, some (like Dutch and German) closely related and others (like Basque) almost unique; and within every language there are many different dialects, some almost unintelligible to members of the mainstream culture. In the language of dress, too, each individual speaker employs subtly personal variations of tone and construction.

The vocabulary of dress consists of items of clothing and styles of makeup, hairdo, body painting, and the like. Occasionally, of course, practical considerations enter into the choice of these items: considerations of comfort, durability, availability, or price. Especially in the case of persons of limited ward-robe, an article may be worn mainly because it is warm or rainproof or handy to cover up a wet bathing suit—in the same way that persons of limited vocabulary use the phrase “you know” or adjectives like “fantastic.” Yet, just as with the spoken language, such choices give some information, even if it is only equivalent to the statement “I don’t give a hoot in hell what I look like.” And there are limits even here. For instance, most American men, however cold or wet they might be, would not put on a woman’s dress.

A complete costume, deliberately chosen, on the other hand, may convey many different messages at once, providing us simultaneously with information about the age, sex, occupation, beliefs, tastes, desires, and mood of its wearer. In America a so-called “fashion leader” will have several hundred “words” at his or her disposal, many of them rare or specialized in other ways, and thus be able to form literally millions of “sentences” expressing a wide range and subtle variations of meaning, qualified with a great many elegant “adjectives” or accessories. The sartorial vocabulary of a migrant farm worker, by contrast, may be limited to some five or ten colloquial terms, from which it is mathematically possible to create only a comparatively few “sentences,” almost bare of decoration and expressing the simplest concepts.

It is quite true that nowadays the extensive dress vocabulary of expensive persons is apt to include some slang or colloquial items: a red windbreaker printed with football numerals, or a mechanic’s white jumpsuit. But their use is always carefully regulated to make certain that the total effect will be sporty, piquant, or “sincere” rather than in either sense vulgar. The rule, as with the spoken language, is that only one or at most two such “words” may be used in a “sentence” or total costume, which must be otherwise impeccably fashionable. The red wind-breaker is worn with obviously expensive pants and shoes, the jumpsuit is hung with a dozen heavy gold chains.

Articles of clothing from the past are used in somewhat the same way, just as a writer or speaker might employ archaisms: always a single “word”—a pair of 1940s platform shoes or an Edwardian waistcoat—never a complete costume, which instead of suggesting sophistication or wit would merely convey the information that one was on one’s way to a masquerade, acting in a play or film, or—far worse—ignorantly out-of-date. The sight of a white plastic Courrèges raincoat and boots (in 1963 the height of fashion) at a New York party or gallery opening today would produce the same shiver of ridicule and revulsion as the use of words like “groovy,” “negro,” or “self-actualizing.”

Dress also contains terms the impact of which moderates with time. Just as words like “naughty” and “mischievous,” once applied to the blackest thoughts and deeds, now describe endearingly childish misbehavior, so heavy eye-makeup is no longer the sign of the man-eating vamp but of the flirtatious teenager. Similar evolutionary changes occur in the sartorial equivalent of “dirty words”: the skin-tight sweater, the man’s shirt open to the waist, etc.

In Taste and Fashion,2 one of the best and most original books on costume, James Laver proposed a timetable for such changes. According to him, the same costume will be:

Mr. Laver’s timetable possibly over-emphasizes the shock value of incoming fashion, which may sometimes be seen merely as weird or ugly. And, of course, he is speaking of the complete costume, or “sentence”; the speed with which a single item passes in and out of fashion may vary, just as in spoken and written languages. Etymological rules remain to be worked out, but it has already been suggested that foreign “words” become and remain popular in rough relation to the international power of their native land. So Madison Avenue has recently seen a flurry of Communist Chinese quilted jackets, followed by a more serious and probably longer-lasting out-break of Arab caftans and turbans, and Russian embroidered blouses and shawls and skirts—the latter passing under the euphemism “rich peasant look.” (The related fondness of counterculture types for items of East or American Indian origin speaks equally clearly, with the number of Indian articles worn at once corresponding fairly accurately to the depth of commitment to vegetarian cookery, transcendental meditation, yoga, astrology, etc.)

Advertisement

In general, items which enter the fashionable vocabulary from a working-class or rural source seem to have a longer life span than those which originate in the underworld. The thigh-high patent leather boot, first worn by the most obvious variety of rentable female as a sign that she was willing to help act out certain male fantasies, shot with relative speed into and out of high fashion; while blue jeans made their way upward much more gradually from sport to daytime to evening use, and are only now beginning a slow descent.

The “grammar” of clothing, or study of the functions and relations of individual items in a “sentence” or costume, is a more difficult subject, one that needs an analyst skilled both in structural linguistics and the history of clothing. Such a scholar might, for instance, be able to explain the current function of blue jeans. Ninety percent of middle-class high school and college students of both sexes are now identical below the waist, though above it they may wear anything from a lumberjack shirt to a lace blouse. One possibility is that this costume is a sign that in their lower or emotional and physical natures these persons are alike, however dissimilar they may be aesthetically, intellectually, or socially. The opposite of such a statement can be imagined, and was actually made by my college classmates thirty years ago. During the daytime we wore identical baggy sweaters over a wide range of slacks, plaid and fringed kilts, full cotton or straight tweed or slinky jersey skirts, and ski pants. “We’re all nice coeds from the waist up,” this costume proclaimed, “but as women we are infinitely various.”

One problem in studying the grammar of dress is the bewildering profusion, not only of languages, but of regional, racial, occupational, and other dialects, some of which are intelligible only to a small in-group—like the knotted-towel code of sexual signals for habitués of public baths recently described in The Village Voice. What is more, all these languages and dialects are continually changing, altering the meaning of individual “words.” Some of these changes may operate according to rules which can be discovered. For example, nearly fifty years ago J.G. Flugel, in The Psychology of Clothes (1930), claimed that the focus of interest gradually shifts from one part of the body to another. And more recently Alison Gernsheim,3 one of the best British historians of costume, pointed out that fashion alternates between bright and neutral colors. When bright colors are in style, muted tints seem drab and dowdy; when soft colors are preferred, as now, brilliant hues and patterns seem vulgar. Rummage-sale racks today are full of splashy ruby and purple and sunset orange and emerald-green imitation Paisley and Art Nouveau print dresses that nobody wants.

Moreover a costume, like a sentence, does not appear in a vacuum, but in association with a specific person in specific circumstances, any change in which will alter its meaning. Like the remark “Let’s get on with this damn business,” the three-piece tan business suit and boldly striped shirt and tie which signify casual conformity at an office meeting will have quite another resonance at a funeral or picnic. And the meaning of this costume will alter according to whether it is worn by a fifty-year-old man, a thirty-year-old woman, or a ten-year-old child.

We must also consider the intonation in which the sentence “‘Let’s get on with this damned business” is spoken; and in the same way we will observe whether the suit fits well or is too large or small; whether it is old or new; and whether it is clean and pressed, slightly rumpled, or definitely filthy. We will take into account the physical attributes of the individual who is wearing this costume, assessing him or her according to height, weight, posture, physical type, and facial features and expression. The same suit will look different on a person whose face and body we consider attractive than on one whom we think ugly. (Of course, the idea of “attractiveness” is also subject to the historical and geographical vagaries of fashion, as Sir Kenneth Clark has brilliantly demonstrated in The Nude.)

Advertisement

Finally, there is the problem that any language which is able to convey information4 can also convey misinformation. A costume may be a lie, either conscious—Cinderella’s ballgown and the radical disguise of the FBI informant—or unconscious. It may be involuntary—as when a child is forced into party clothes by a parent—or voluntary. The long and complex history of the uniform, from boy scout and waitress to priest and five-star general, probably belongs here.

The serious study of costume has largely concentrated on what has been worn by the well-to-do classes in Western Europe and America over the last three centuries, probably because of its high visibility and the wide availability of sources. Several very good books have been written on the subject, and many theories proposed to explain why fashions change. J.G. Flugel saw it as an attempt to stimulate the opposite sex by exposing first one and then another area of the body. James Laver, while partly endorsing this view, also believes that styles in dress reflect what he, though with British reluctance, calls a Zeitgeist: “The Republican yet licentious notions of the Directoire find their echo in the plain transparent dresses of the time. Victorian modesty expressed itself in the multiplicity of petticoats; the emancipation of the post-War flapper in short hair and short skirts.”

Recently Laver’s theories have been elegantly applied to European costume from 1560 to 1860 by Geoffrey Squire. (The title of his large, attractive, and agreeably written book, Dress and Society, 1560-1970, is misleading: all the illustrations show clothes worn before 1860, and the subsequent 110 years are squeezed into a few pages at the end.) Geoffrey Squire is particularly good on the relation of costume to the fine and applied arts, comparing the artificial forms and fine detailing of Elizabethan dress to Mannerist poetry and painting, for instance, and the full rounded forms of seventeenth-century costume to the paintings of Van Dyke and Rubens.

Quentin Bell, whose erudite and witty On Human Finery is now reissued in a revised and expanded edition, follows Thorstein Veblen in designating economic competition as the principal force behind the vicissitudes of fashion. According to him, the purpose of dress in the middle and upper classes is to display wealth upon the person. This is done, as Veblen suggested, through Conspicuous Consumption (mink, diamonds, superfluous petticoats, etc.), Conspicuous Leisure (platform shoes, trailing skirts, white linen suits, and any other “visible evidence that one is leading an honorably futile existence”), and Conspicuous Waste. To these three categories he adds one of his own, Conspicuous Outrage. This usually takes the form of deliberately appearing in clothes which do not conform to the current rules of “good taste”—which, as a recent textbook remarks, “is a measure of [an individual’s] ability to live up to the group standard.”5

It is Conspicuous Outrage which causes persons to appear at parties given by those to whom they feel (or wish to feel) superior in casual or strikingly untidy dress, thus silently announcing to all who see them that they are slumming. The same ploy is frequently, and perhaps more understandably, adopted by artists who have been invited to dinner by their patrons—whose ward-robes are sure to offer much more in the way of conspicuous consumption, leisure, and waste.

On Human Finery is full of entertaining insights into such things as the costumes in “historical” paintings, the use of the domestic animal as a fashion accessory (“expense and futility are the criteria”), and the relative prestige of various sports and hence of the clothes associated with them (“the most English of sports and that which has had the most decided effect upon clothes [consists] in the pursuit of an ‘inedible animal,’ with an expensive pack of hounds, a great assembly of expensive horses and expensive ladies and gentlemen, many of them wearing a kind of uniform and with a stiff bill for damages at the end”).

Professor Bell ends his book with the declaration that “fashion in clothes, as we know it, is coming to an end,” basing this view on observation of the sartorial “anarchy” of his students at Sussex University, and the belief that “the death of fashion in the universities will presently lead to its destruction everywhere.” Unless English campuses are very different from American ones, this seems to me an error. Statements made in a strange language always sound like anarchic nonsense, and though not by any means fluent in this tongue, I know that student costume obeys its own grammatical rules. “The young woman who came draggle-haired, barefoot, in mended trousers and plebeian shirt to voice the doctrines of Chairman Mao at last Tuesday’s tutorial” and “appears at Wednesday’s seminar prim and pretty with flounces down to her ankles and her hair neatly bound in a knot” is not as he suggests rejecting fashion, but following it, carefully suiting her costume to her role just as Professor Bell himself might do. And there are rules within rules: according to my teenage son, the very brand of blue jeans worn in junior high school is a sign: “freaks always wear Lees, greasers wear Wranglers, and everyone else wears Levis.”

The voice of fashion has not fallen silent; rather it screams in a thousand languages and dialects.6 As for conspicuous consumption, it literally speaks louder than ever, as in those T-shirts worn by my students which have the name of their maker stamped across the chest in letters two inches high. “Addidas are the best T-shirts,” my son explains. “Well, they’re pretty much like other T-shirts really, but they cost more, and they have the name on them.”

This reliance on the printed brand name is now widespread, and not only in schools and colleges. Fashionable men and women used to be able to recognize London tailoring or real lace and hand embroidery at a glance. But the wish and economic ability to consume conspicuously now extends to millions of people who are ignorant of such subtleties. Therefore the most desirable articles of dress are clearly marked with the names of their manufacturers. There has, for instance, been a great boom in the sale of very ugly brown plastic handbags which, because they are boldly stamped with the letters “LV,” are known even by the semi-ignorant to cost much more than other ugly brown plastic handbags. It is difficult to imagine a more blatant display of wealth, short of working the price tag itself into the design.

Possibly Professor Bell, a man of considerable aesthetic sensitivity, simply does not recognize this sort of thing as fashion. Or perhaps he has been misled by the claim, made rather often of late in magazines like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, that fashion is dead. As Tom Wolfe points out in “Funky Chic,”7 this is merely a rhetorical gesture. Rich women may declare in interviews that they chose their clothes for “ease, comfort, convenience, practicality, simplicity,” etc., but these practical simple clothes always turn out to have been bought very recently from the most expensive designers.

In modern times the obvious showplace for conspicuous consumption has been the films. Waste on a grand scale is one of the characteristics of movie making: waste of talent, waste of energy, waste of materials, waste of money, and waste of time—as anyone who has spent even a couple of hours on a movie set knows. From a Veblenite point of view, what could be more attractive and generate more prestige?

Theatrical extravagance, of course, has a long history. Yet it has been exceeded by the extravagance of the film industry. Stage costume, however elaborate, is made to be worn: if a play is successful, each garment will get many more hours of vigorous use than it would in real life. In the movies, however, months of work and thousands of dollars can be spent on something that will be worn for only a few minutes. Perhaps the most famous example is Edith Head’s dance outfit for Ginger Rogers in Lady in the Dark (1943), billed in publicity releases as the most expensive costume in the world: it was paved with red and gold sequins and trimmed in mink, and cost $35,000.

Granted, the principles of theatrical costuming could not be transferred directly to films. Clothes for the stage must be designed for large-scale effect: subtle tailoring and delicate patterns are invisible beyond the second row; everything must be exaggerated so that it can be seen at the back of the auditorium. In a movie, on the other hand, an inch of ribbon can appear ten feet long on screen, showing every stitch. Yet the importance given to costume in Hollywood, almost from the start, was well beyond the requirements of the medium. It may be no coincidence that most of the early movie magnates started out in the fashion business, as Dale McConathy points out. Louis B. Mayer was a shoemaker, Samuel Goldwyn a glovemaker, and Adolph Zukor a furrier before they got to Hollywood, and all three men brought friends and colleagues from the garment trade with them into the film industry.

Because of dramatic convention and the visual distance from performer to viewer, stage costume has been able to emphasize appearance rather than reality. Great theater, as Barthes remarks in “The Diseases of Costume,” relies on the imaginative power of the spectator, who is capable of “transforming rayon into silk and lies into illusion,” rather than attempting to overwhelm his disbelief with authentic historical detail, formal beauty, or obvious expenditure. Even at Stratford-on-Avon the king’s ermine and sable robes are either dyed rabbit or synthetic fur, which not only costs less but is lighter to carry on stage; and the jewelry is paste.

The Hollywood producers, however, were not content with appearance; they demanded the use of the most expensive materials even when a cheaper substitute would completely deceive the camera. Adolph Zukor, for instance, insisted on real fur trimmings for all the costumes in his films, declaring that it was “good for the business.” And in some of the film extravaganzas of the Thirties and Forties even the extras were dressed like kings and queens. For Marie Antoinette (1938), Adrian designed 4,000 lavishly authentic costumes, using real eighteenth-century bits of silk, velvet, lace, and embroidery. Norma Shearer, the star, had thirty-four costume changes and eighteen wigs, one frosted with real diamonds. In these get-ups her mobility, like Marie Antoinette’s, was severely limited; but this was no novelty for Hollywood films, where skirts were often so wide that it was impossible to get in or out of a dressing-room. Or, at the other extreme, so tightly fitted to the body and armored with beads and embroidery that one could not sit down or even walk naturally.

Clothes like this, in their elaborate decoration, fantastic cost, physical inconvenience, and infrequency of use, recall not so much stage costume as the extravagantly embroidered and bejeweled vestments of religion, assumed only for a few moments of supernatural importance. And this is as it should be, for (as has often been said) the stars of Hollywood are our demigods and goddesses—the deities of what is in more ways than one a pagan society. Pure monotheism has always been a difficult and abstract faith. The popular mind is uncomfortable with the idea of a single God who embodies all known qualities. What it wants is something closer to the Greek pantheon, with appropriate gods and goddesses for each admired virtue—or admired vice: a Venus, a Diana, a Vulcan, a Mars. (We also need local and minor deities: the Brilliant American Novelist, Christmas Seal Child of the Year, or Tompkins County Dairy Princess.) And, like some pagans, we destroy our gods, or rather their human avatars, at frequent intervals, replacing them with new ones—thus even in our spiritual life following Veblen’s principle of Conspicuous Waste.

Some of the record of this process can be found in Dale McConathy’s Hollywood Costume—Glamour! Glitter! Romance! which in spite of its unpromising title is full of striking facts and figures (both kinds), entertaining anecdotes, and shrewd analysis of the style and careers of many Hollywood goddesses from Theda Bara to Barbra Streisand (and a few gods), with special attention to their appearance and dress, both on and off camera. The book itself is designed like a camp Hollywood production: huge, lavishly pictorial in both black-and-white and technicolor, and bound in a flowered pink and gold brocade which, like some film costumes, gives the effect of being both stylishly expensive and vulgarly cheap at the same time. It is protected, appropriately, by a dust jacket of what appears to be celluloid.

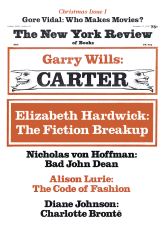

This Issue

November 25, 1976

-

1

In Critical Essays (Northwestern University Press, 1972).

↩ -

2

Harrap, London, 1945.

↩ -

3

Fashion and Reality (Faber and Faber, London, 1963).

↩ -

4

A current paperback, Dress for Success, by John T. Molloy, tells businessmen how to choose their clothes so that they will look efficient, authoritative, and reliable, even when they are inefficient, weak, and shifty.

↩ -

5

Mary Ellen Roach and Joan B. Eicher, The Visible Self: Perspectives on Dress (Prentice-Hall, 1973).

↩ -

6

In addition, its symbolic language has now become overlaid with printed verbal messages. T-shirts advertise favorite products, cultural tastes (VILLAGE VOICE, JEFFERSON STAR-SHIP), political opinions, membership in real or imaginary organizations (HARVARD UNIVERSITY, OLYMPIC SCREWING TEAM), real or imaginary personality (FOXY LADY, MALE CHAUVINIST PIG), sexual preference (GAY POWER, EAT ME), and current mood (SMILE, BLUE MONDAY).

↩ -

7

In Mauve Gloves & Madmen, Clutter & Vine (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1976).

↩