Forty-nine years ago last October Al Jolson not only filled with hideous song the sound track of a film called The Jazz Singer, he also spoke. With the words “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet” (surely the most menacing line in the history of world drama), the age of the screen director came to an end and the age of the screenwriter began.

Until 1927, the director was king, turning out by the mile his “molds of light” (André Bazin’s nice phrase). But once the movies talked, the director as creator became secondary to the writer. Even now, except for an occasional director-writer like Ingmar Bergman,1 the director tends to be the one interchangeable (if not entirely expendable) element in the making of a film. After all, there are thousands of movie technicians who can do what a director is supposed to do because, in fact, collectively (and sometimes individually) they actually do do his work behind the camera and in the cutter’s room. On the other hand, there is no film without a written script.

In the Fifties when I came to MGM as a contract writer and took my place at the Writers’ Table in the commissary, the Wise Hack used to tell us newcomers, “The director is the brother-in-law.” Apparently the ambitious man became a producer (that’s where the power was). The talented man became a writer (that’s where the creation was). The pretty man became a star.

Even before Jolson spoke, the director had begun to give way to the producer. Director Lewis Milestone saw the writing on the screen as early as 1923 when “baby producer” Irving Thalberg fired the legendary director Erich von Stroheim from his film Merry Go Round. “That,” wrote Milestone somberly in New Theater and Film (March 1937), “was the beginning of the storm and the end of the reign of the director….” Even as late as 1950 the star Dick Powell assured the film cutter Robert Parrish that “anybody can direct a movie, even I could do it. I’d rather not because it would take too much time. I can make more money acting, selling real estate and playing the market.”2 That was pretty much the way the director was viewed in the Thirties and Forties, the so-called classic age of the talking movie.

Although the essential creator of the classic Hollywood film was the writer, the actual master of the film was the producer, as Scott Fitzgerald recognized when he took as protagonist for his last novel Irving Thalberg. Although Thalberg himself was a lousy movie-maker, he was the head of production at MGM; and in those days MGM was a kind of Vatican where the chief of production was Pope, holding in his fists the golden keys of Schenck. The staff producers were the College of Cardinals. The movie stars were holy and valuable objects to be bought, borrowed, stolen. Like icons, they were moved from sound stage to sound stage, studio to studio, film to film, bringing in their wake good fortune and gold.

With certain exceptions (Alfred Hitchcock, for one), the directors were, at worst, brothers-in-law; at best, bright technicians. All in all, they were a cheery, unpretentious lot, and if anyone had told them that they were auteurs du cinéma, few could have coped with the concept, much less the French. They were technicians; proud commercialites, happy to serve what was optimistically known as The Industry.

This state of affairs lasted until television replaced the movies as America’s principal dispenser of mass entertainment. Overnight the producers lost control of what was left of The Industry and, unexpectedly, the icons took charge. Apparently, during all those years when we thought the icons nothing more than beautifully painted images of all our dreams and lusts, they had been not only alive but secretly greedy for power and gold.

“The lunatics are running the asylum,” moaned the Wise Hack at the Writers’ Table, but soldiered on. Meanwhile, the icons started to produce, direct, even write. For a time, they were able to ignore the fact that with television on the rise, no movie star could outdraw the “$64,000 Question.” During this transitional decade, the director was still the brother-in-law. But instead of marrying himself off to a producer, he shacked up, as Jimmy Carter would say, with an icon. For a time each icon had his or her favorite director and The Industry was soon on the rocks.

Then out of France came the dreadful news: all those brothers-in-law of the classic era were really autonomous and original artists. Apparently each had his own style that impressed itself on every frame of any film he worked on. Proof? Since the director was the same person from film to film, each image of his oeuvre must then be stamped with his authorship. The argument was circular but no less overwhelming in its implications. Much quoted was Giraudoux’s solemn inanity: “There are no works, there are only auteurs.”

Advertisement

The often wise André Bazin eventually ridiculed this notion in La Politique des Auteurs, but the damage was done in the pages of the magazine he founded, Cahiers du cinéma. The fact that, regardless of director, every Warner Brothers film during the classic age had a dark look owing to the Brothers’ passion for saving money in electricity and set-dressing cut no ice with ambitious critics on the prowl for high art in a field once thought entirely low.

In 1948, Bazin’s disciple Alexandre Astruc wrote the challenging “La Caméra-stylo.” This manifesto advanced the notion that the director is—or should be—the true and solitary creator of a movie, “penning” his film on celluloid. Astruc thought that caméra-stylo could

tackle any subject, any genre…. I will even go so far as to say that contemporary ideas and philosophies of life are such that only the cinema can do justice to them. Maurice Nadeau wrote in an article in the newspaper Combat: “If Descartes lived today, he would write novels.” With all due respect to Nadeau, a Descartes of today would already have shut himself up in his bedroom with a 16mm camera and some film, and would be writing his philosophy on film: for his Discours de la Méthode would today be of such a kind that only the cinema could express it satisfactorily.3

With all due respect to Astruc, the cinema has many charming possibilities but it cannot convey complex ideas through words or even, paradoxically, dialogue in the Socratic sense. Le Genou de Claire is about as close as we shall ever come to dialectic in a film and though Rohmer’s work has its delights, the ghost of Descartes is not very apt to abandon the marshaling of words on a page for the flickering shadows of talking heads. In any case, the Descartes of Astruc’s period did not make a film; he wrote the novel La Nausée.

But the would-be camera-writers are not interested in philosophy or history or literature. They want only to acquire for the cinema the prestige of ancient forms without having first to crack, as it were, the code. “Let’s face it,” writes Astruc:

between the pure cinema of the 1920s and filmed theater, there is plenty of room for a different and individual kind of film-making.

This of course implies that the scriptwriter directs his own scripts; or rather, that the scriptwriter ceases to exist, for in this kind of film-making the distinction between author and director loses all meaning. Direction is no longer a means of illustrating or presenting a scene, but a true act of writing.

It is curious that despite Astruc’s fierce will to eliminate the scriptwriter (and perhaps literature itself), he is forced to use terms from the art form he would like to supersede. For him the film director uses a pen with which he writes in order to become—highest praise—an author.

As the French theories made their way across the Atlantic, bemused brothers-in-law found themselves being courted by odd-looking French youths with tape recorders. Details of longforgotten Westerns were recalled and explicated. Every halting word from the auteur’s lips was taken down and reverently examined. The despised brothers-in-law of the Thirties were now Artists. With new-found confidence, directors started inking major pacts to meg superstar thesps whom the meggers could control as hyphenates: that is, as director-producers or even as writer-director-producers. Although the icons continued to be worshipped and overpaid, the truly big deals were now made by directors. To them, also, went the glory. For all practical purposes the producer has either vanished from the scene (the “package” is now put together by a talent [!] agency) or merged with the director. Meanwhile, the screenwriter continues to be the prime creator of the talking film, and though he is generally paid very well and his name is listed right after that of the director in the movie reviews of Time, he is entirely in the shadow of the director just as the director was once in the shadow of the producer and the star.

What do directors actually do? What do screenwriters do? This is difficult to explain to those who have never been involved in the making of a film. It is particularly difficult when French theoreticians add to the confusion by devising false hypotheses (studio director as auteur in the Thirties) on which to build irrelevant and misleading theories. Actually, if Astruc and Bazin had wanted to be truly perverse (and almost accurate), they would have declared that the cameraman is the auteur of any film. They could then have ranked James Wong Howe with Dante, Braque, and Gandhi. Cameramen do tend to have styles in a way that the best writers do but most directors don’t—style as opposed to preoccupation. Gregg Toland’s camera work is a vivid fact from film to film, linking Citizen Kane to Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives in a way that one cannot link Citizen Kane to, say, Welles’s Confidential Report. Certainly the cameraman is usually more important than the director in the day-to-day making of a film as opposed to the preparing of a film. Once the film is shot the editor becomes the principal interpreter of the writer’s invention.

Advertisement

Since there are few reliable accounts of the making of any of the classic talking movies, Pauline Kael’s book on the making of Citizen Kane is a valuable document.4 In considerable detail she establishes the primacy in that enterprise of the screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz. The story of how Orson Welles saw to it that Mankiewicz became, officially, the noncreator of his own film is grimly fascinating and highly typical of the way so many director-hustlers acquire for themselves the writer’s creation. Few directors in this era possess the modesty of Kurosawa, who said, recently, “With a very good script, even a second-class director may make a first-class film. But with a bad script even a first-class director cannot make a really first-class film.” The badness of so many of Orson Welles’s post-Mankiewicz films ought to be instructive.

A useful if necessarily superficial look at the way movies were written in the classic era can be found in the pages of Some Time in the Sun. The author, Mr. Tom Dardis, examines the movie careers of five celebrated writers who took jobs as movie-writers. They are Scott Fitzgerald, Aldous Huxley, William Faulkner, Nathanael West, and James Agee.

Mr. Dardis’s approach to his writers and to the movies is that of a deeply serious and highly concerned lowbrow, a type now heavily tenured in American Academe. He writes of “literate” dialogue, “massive” biographies. Magisterially, he misquotes Henry James on the subject of gold. More seriously, he misquotes Joan Crawford. She did not say to Fitzgerald, “Work hard, Mr. Fitzgerald, work hard!” when he was preparing a film for her. She said “Write hard….” There are many small inaccuracies that set on edge the film buff’s teeth. For instance, Mr. Dardis thinks that the hotel on Sunset Boulevard known, gorgeously, as The Garden of Allah is “now demolished and reduced to the status of a large parking lot….” Well, it is not a parking lot. Hollywood has its own peculiar reverence for the past. The Garden of Allah was replaced by a bank that subtly suggests in glass and metal the mock-Saracen façade of the hotel that once housed Scott Fitzgerald. Mr. Dardis also thinks that the hotel was “demolished” during World War II. I stayed there in the late Fifties, right next door to funloving, bibulous Errol Flynn.

Errors and starry-eyed vulgarity to one side, Mr. Dardis has done a good deal of interesting research on how films were written and made in those days. For one thing, he catches the ambivalence felt by the writers who had descended (but only temporarily) from literature’s Parnassus to the swampy marketplace of the movies. There was a tendency to play Lucifer. One was thought to have sold out. “Better to reign in hell than to serve in heaven,” was more than once quoted—well, paraphrased—at the Writers’ Table. We knew we smelled of sulphur. Needless to say, most of the time it was a lot of fun if the booze didn’t get you.

For the Parnassian writer the movies were not just a means of making easy money; even under the worst conditions, movies were genuinely interesting to write. Mr. Dardis is at his best when he shows his writers taking seriously their various “assignments.” The instinct to do good work is hard to eradicate.

Faulkner was the luckiest (and the most cynical) of Mr. Dardis’s five. For one thing, he usually worked with Howard Hawks, a director who might actually qualify as an auteur. Hawks was himself a writer and he had a strong sense of how to manipulate those clichés that he could handle best. Together Faulkner and Hawks created a pair of satisfying movies, To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep. But who did what? Apparently there is not enough remaining evidence (at least available to Mr. Dardis) to sort out authorship. Also, Faulkner’s public line was pretty much: I’m just a hired hand who does what he’s told.

Nunnally Johnson (as quoted by Mr. Dardis) found Hawks’s professional relationship with Faulkner mysterious. “It may be that he simply wanted his name attached to Faulkner’s. Or since Hawks liked to write it was easy to do it with Faulkner, for Bill didn’t care much one way or the other….” We shall probably never know just how much Bill cared about any of the scripts he worked on with Hawks. Yet it is interesting to note that Johnson takes it entirely for granted that the director wants—and must get—all credit for a film.

Problem for the director: how to get a script without its author? Partial solution: of all writers, the one who does not mind anonymity is the one most apt to appeal to an ambitious director. When the studio producer was king, he used to minimize the writer’s role by assigning a dozen writers to a script. No director today has the resources of the old studios. But he can hire a writer who doesn’t “care much one way or the other.” He can also put his name on the screen as co-author (standard procedure in Italy and France). Even the noble Jean Renoir played this game when he came to direct The Southerner. Faulkner not only wrote the script, he liked the project. The picture’s star Zachary Scott has said that the script was entirely Faulkner’s. But then other hands were engaged and “the whole problem,” according to Mr. Dardis, “of who did what was neatly solved by Renoir’s giving himself sole credit for the screenplay—the best way possible for an auteur director to label his films.”

Unlike Faulkner, Scott Fitzgerald cared deeply about movies; he wanted to make a success of movie writing and, all in all, if Mr. Dardis is to be believed (and for what it may be worth, his account of Fitzgerald’s time in the sun tallies with what one used to hear), he had a far better and more healthy time of it in Hollywood than is generally suspected.

Of a methodical nature, Fitzgerald ran a lot of films at the studio. (Unlike Faulkner, who affected to respond only to Mickey Mouse and Pathé News). Fitzgerald made notes. He also did what an ambitious writer must do if he wants to write the sort of movie he himself might want to see: he made friends with the producers. Rather censoriously, Mr. Dardis notes Fitzgerald’s “clearly stated intention to work with film producers rather than with film directors, here downgraded to the rank of ‘collaborators.’ Actually, Fitzgerald seems to have had no use whatsoever for directors as such.” But neither did anyone else.

During much of this time Howard Hawks, say, was a low-budget director known for the neatness and efficiency of his work. Not until the French beatified him twenty years later did he appear to anyone as an original artist instead of just another hired technician. It is true that Hawks was allowed to work with writers but then he was at Warner Brothers, a frontier outpost facing upon barbarous Burbank. At MGM, the holy capital, writers and directors did not get much chance to work together. It was the producer who worked with the writer, and Scott Fitzgerald was an MGM writer. Even as late as my own years at MGM (1956-1958), the final script was the writer’s creation (under the producer’s supervision). The writer even pre-empted the director’s most important function by describing each camera shot: Long, Medium, Close, and the director was expected faithfully to follow the writer’s score.

One of the most successful directors at MGM during this period was George Cukor. In an essay on “The Director” (1938), Cukor reveals the game as it used to be played. “In most cases,” he writes, “the director makes his appearance very early in the life story of a motion picture.” I am sure that this was often the case with Cukor but the fact that he thinks it necessary to mention “early” participation is significant.

There are times when the whole idea for a film may come from [the director], but in a more usual case he makes his entry when he is summoned by a producer and it is suggested that he should be the director of a proposed story.5

Not only was this the most usual way but, very often, the director left the producer’s presence with the finished script under his arm. Cukor does describe his own experience working with writers but Cukor was something of a star at the studio. Most directors were “summoned” by the producer and told what to do. It is curious, incidentally, how entirely the idea of the working producer has vanished. He is no longer remembered except as the butt of familiar stories: fragile artist treated cruelly by insensitive cigar-smoking producer—or Fitzgerald savaged yet again by Joe Mankiewicz.

Of Mr. Dardis’s five writers, James Agee is, to say the least, the lightest in literary weight. But he was a passionate film-goer and critic. He was a child of the movies just as Huxley was a child of Meredith and Peacock. Given a different temperament, luck, birthdate, Agee might have been the first American cinema auteur: a writer who wrote screenplays in such a way that, like the score of a symphony, they needed nothing more than a conductor’s interpretation,…an interpretation he could have provided himself and perhaps would have provided if he had lived.

Agee’s screenplays were remarkably detailed. “All the shots,” writes Mr. Dardis, “were set down with extreme precision in a way that no other screenwriter had ever set things down before….” This is exaggerated. Most screenwriters of the classic period wrote highly detailed scripts in order to direct the director but, certainly, the examples Mr. Dardis gives of Agee’s screenplays show them to be remarkably visual. Most of us hear stories. He saw them, too. But I am not so sure that what he saw was the reflection of a living reality in his head. As with many of today’s young directors, Agee’s memory was crowded with memories not of life but of old films. For Agee, rain falling was not a memory of April at Exeter but a scene recalled from Eisenstein. This is particularly noticeable in the adaptation Agee made of Stephen Crane’s The Blue Hotel, which, Mr. Dardis tells us, no “film director has yet taken on, although it has been televised twice, each time with a different director and cast and with the Agee script cut to the bone, being used only as a guidepost to the story.” This is nonsense. In 1954, CBS hired me to adapt The Blue Hotel. I worked directly from Stephen Crane and did not know that James Agee had ever adapted it until I read Some Time in the Sun.

At the mention of any director’s name, the Wise Hack at the Writers’ Table would bark out a percentage, representing how much, in his estimate, a given director would subtract from the potential 100 percent of the script he was directing. The thought that a director might add something worthwhile never crossed the good gray Hack’s mind. Certainly he would have found hilarious David Thomson’s A Biographical Dictionary of Film, whose haphazard pages are studded with tributes to directors.

Mr. Thomson has his own pleasantly eccentric pantheon in which writers figure hardly at all. A column is devoted to the dim Micheline Presle but the finest of all screenwriters, Jacques Prévert, is ignored. There is a long silly tribute to Arthur Penn; yet there is no biography of Penn’s contemporary at NBC television, Paddy Chayefsky, whose films in the Fifties and early Sixties were far more interesting than anything Penn has done. Possibly Chayefsky was excluded because not only did he write his own films, he would then hire a director rather the way one would employ a plumber—or a cameraman. For a time, Chayefsky was the only American auteur, and his pencil was the director. Certainly Chayefsky’s early career in films perfectly disproves Nicholas Ray’s dictum (approvingly quoted by Mr. Thomson): “If it were all in the script, why make the film?” If it is not all in the script, there is no film to make.

Twenty years ago at the Writers’ Table we all agreed with the Wise Hack that William Wyler subtracted no more than 10 percent from a script. Some of the most attractive and sensible of Bazin’s pages are devoted to Wyler’s work in the Forties. On the other hand, Mr. Thomson does not like him at all (because Wyler lacks those redundant faults that create the illusion of a Style?). Yet whatever was in a script, Wyler rendered faithfully: when he was given a bad script, he would make not only a bad movie, but the script’s particular kind of badness would be revealed in a way that could altogether too easily boomerang on the too skillful director. But when the script was good (of its kind, of its kind!), The Letter, say, or The Little Foxes, there was no better interpreter.

At MGM, I worked exclusively with the producer Sam Zimbalist. He was a remarkably good and decent man in a business where such qualities are rare. He was also a producer of the old-fashioned sort. This meant that the script was prepared for him and with him. Once the script was ready, the director was summoned; he would then have the chance to say, yes, he would direct the script or, no, he wouldn’t. Few changes were made in the script after the director was assigned. But this was not to be the case in Zimbalist’s last film.

For several years MGM had been planning a remake of Ben-Hur, the studio’s most successful silent film. A Contract Writer wrote a script; it was discarded. Then Zimbalist offered me the job. I said no, and went on suspension. During the next year or two S.N. Behrman and Maxwell Anderson, among others, added many yards of portentous dialogue to a script which kept growing and changing. The result was not happy. By 1958 MGM was going bust. Suddenly the remake of Ben-Hur seemed like a last chance to regain the mass audience lost to television. Zimbalist again asked me if I would take on the job. I said that if the studio released me from the remainder of my contract, I would go to Rome for two or three months and rewrite the script. The studio agreed. Meanwhile, Wyler had been signed to direct.

On a chilly March day Wyler, Zimbalist, and I took an overnight flight from New York. On the plane Wyler read for the first time the latest of the many scripts. As we drove together into Rome from the airport, Wyler looked gray and rather frightened. “This is awful,” he said, indicating the huge script that I had placed between us on the back seat. “I know,” I said. “What are we going to do?”

Wyler groaned: “These Romans…. Do you know anything about them?” I said, yes, I had done my reading. Wyler stared at me. “Well,” he said, “when a Roman sits down and relaxes, what does he unbuckle?”

That spring I rewrote more than half the script (and Wyler studied every “Roman” film ever made). When I was finished with a scene, I would give it to Zimbalist. We would go over it. Then the scene would be passed on to Wyler. Normally, Wyler is slow and deliberately indecisive; but first-century Jerusalem had been built at enormous expense; the first day of shooting was approaching; the studio was nervous. As a result, I did not often hear Wyler’s famous cry, as he would hand you back your script, “If I knew what was wrong with it, I’d fix it myself.”

The plot of Ben-Hur is, basically, absurd and any attempt to make sense of it would destroy the story’s awful integrity. But for a film to be watchable the characters must make some kind of psychological sense. We were stuck with the following: the Jew Ben-Hur and the Roman Messala were friends in childhood. Then they were separated. Now the adult Messala returns to Jerusalem; meets Ben-Hur; asks him to help with the Romanization of Judea. Ben-Hur refuses; there is a quarrel; they part and vengeance is sworn. This one scene is the sole motor that must propel a very long story until Jesus Christ suddenly and pointlessly drifts onto the scene, automatically untying some of the cruder knots in the plot. Wyler and I agreed that a single political quarrel would not turn into a lifelong vendetta.

I thought of a solution, which I delivered into Wyler’s good ear. “As boys they were lovers. Now Messala wants to continue the affair. Ben-Hur rejects him. Messala is furious. Chagrin d’amour, the classic motivation for murder.”

Wyler looked at me as if I had gone mad. “But we can’t do that! I mean this is Ben-Hur! My God….”

“We won’t really do it. We just suggest it. I’ll write the scenes so that they will make sense to those who are tuned in. Those who aren’t will still feel that Messala’s rage is somehow emotionally logical.”

I don’t think Wyler particularly liked my solution but he agreed that “anything is better than what we’ve got. So let’s try it.”

I broke the original scene into two parts. Charlton Heston (Ben-Hur) and Stephen Boyd (Messala) read them for us in Zimbalist’s office. Wyler knew his actors. He warned me: “Don’t ever tell Chuck what it’s all about, or he’ll fall apart.” I suspect that Heston does not know to this day what luridness we managed to contrive around him. But Boyd knew: every time he looked at Ben-Hur it was like a starving man getting a glimpse of dinner through a pane of glass. And so, among the thundering hooves and clichés of the last (to date) Ben-Hur, there is something odd and authentic in one unstated relationship.

As agreed, I left in early summer and Christopher Fry wrote the rest of the script. Before the picture ended, Zimbalist died of a heart attack. Later, when it came time to credit the writers of the film, Wyler proposed that Fry be given screen credit. Then Fry insisted that I be given credit with him since I had written the first half of the picture. Wyler was in a quandary. Only Zimbalist (and Fry and myself—two interested parties) knew who had written what, and Zimbalist was dead. The matter was given to the Screenwriters Guild for arbitration and they, mysteriously, awarded the credit to the Contract Writer whose script was separated from ours by at least two other discarded scripts. The film was released in 1959 (not 1959-1960 as my edition of The Filmgoer’s Companion by Leslie Halliwell states) and saved MGM from financial collapse.

I have recorded in some detail this unimportant business to show the nearimpossibility of determining how a movie is actually created. Had Ben-Hur been taken seriously by, let us say, those French critics who admire Johnny Guitar, then Wyler would have been credited with the unusually subtle relationship between Ben-Hur and Messala. No credit would ever have gone to me because my name was not on the screen, nor would credit have gone to the official scriptwriter because, according to the auteur theory, every aspect of a film is the creation of the director.

The twenty-year interregnum when the producer was supreme is now a memory. The ascendancy of the movie stars was brief. The directors have now regained their original primacy, and Milestone’s storm is only an echo. Today the marquees of movie houses feature the names of directors and journalists (“A work of art,” J. Crist); the other collaborators are in fine print.

This situation might be more acceptable if the film directors had become true auteurs. But most of them are further than ever away from art—not to mention life. The majority are simply technicians. A few have come from the theater; many began as editors, cameramen, makers of television series, and, ominously, of television commercials. In principle, there is nothing wrong with a profound understanding of the technical means by which an image is impressed upon celluloid. But movies are not just molds of light any more than a novel is just inked-over paper. A movie is a response to reality in a certain way and that way must first be found by a writer. Unfortunately, no contemporary film director can bear to be thought a mere interpreter. He must be sole creator. As a result, he is more often than not a plagiarist, telling stories that are not his.

Over the years a number of writers have become directors, but except for such rare figures as Cocteau and Bergman, the writers who have gone in for directing were generally not much better at writing than they proved to be at directing. Even in commercial terms, for every Joe Mankiewicz or Preston Sturges there are a dozen Xs and Ys, not to mention the depressing Z.

Today’s films are more than ever artifacts of light. Cars chase one another mindlessly along irrelevant freeways. Violence seems rooted in a notion about what ought to happen next on the screen to help the images move rather than in any human situation anterior to those images. In fact, the human situation has been eliminated not through any intentional philosophic design but because those who have spent too much time with cameras and machines seldom have much apprehension of that living world without whose presence there is no art.

I suspect that the time has now come to take Astruc seriously…after first rearranging his thesis. Astruc’s camérastylo requires that “the script writer ceases to exist…. The filmmaker/author writes with his camera as a writer writes with his pen.” Good. But let us eliminate not the screenwriter but that technician-hustler—the director (a.k.a. auteur du cinéma). Not until he has been replaced by those who can use a pen to write from life for the screen is there going to be much of anything worth seeing. Nor does it take a genius of a writer to achieve great effects in film. Compared to the works of his nineteenth-century mentors, the writing of Ingmar Bergman is second-rate. But when he writes straight through the page and onto the screen itself his talent is transformed and the result is often first-rate. (As was very often the work of René Clair.)

As a poet, Jacques Prévert is not in the same literary class as Valéry, but Prévert’s Les Enfants du Paradis and Lumière d’été are extraordinary achievements. They were also disdained by the French theoreticians of the Forties who knew perfectly well that the directors Carné and Grémillon were inferior to their scriptwriter; but since the Theory requires that only a director can create a film, any film that is plainly a writer’s work cannot be true cinema. This attitude has given rise to some highly comic critical musings. Recently a movie critic could not figure out why there had been such a dramatic change in the quality of the work of the director Joseph Losey after he moved to England. Was it a difference in the culture? the light? the water? Or could it—and the critic faltered—could it be that perhaps Losey’s films changed when he…when he—oh, dear!—got Harold Pinter to write screenplays for him? The critic promptly dismissed the notion. Mr. Thomson prints no biography of Pinter in his Dictionary.

I have never much liked the films of Pier Paolo Pasolini but I find most interesting the ease with which he turned to film after some twenty years as poet and novelist. He could not have been a filmmaker in America because the costs are too high; also, the technician-hustlers are in total charge. But in Italy, during the Fifties, it was possible for an actual auteur to use for a pen the camera (having first himself composed rather than stolen the narrative to be illuminated).

Since the talking movie is closest in form to the novel (“the novel is a narrative that organizes itself in the world, while the cinema is a world that organizes itself into a narrative”—Jean Mitry), it strikes me that the rising literary generation might think of the movies as, peculiarly, their kind of novel, to be created by them in collaboration with technicians but without the interference of The Director, that hustler-plagiarist who has for twenty years dominated and exploited and (occasionally) enhanced an art form still in search of its true authors.

This Issue

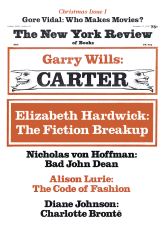

November 25, 1976

-

1

Questions I am advised to anticipate: What about such true auteurs du cinéma as Truffaut? Well, Jules et Jim was a novel by Henri-Pierre Roché. Did Truffaut adapt the screenplay himself? No, he worked with Jean Gruault. Did Buñuel create The Exterminating Angel? No, it was “suggested” by an unpublished play by José Bergamin. Did Buñuel take it from there? No, he had as co-author Luis Alcorisa. So it goes.

↩ -

2

Robert Parrish, Growing Up in Hollywood (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976).

↩ -

3

Astruc’s essay is reprinted in Peter Graham, ed., The New Wave (Doubleday, 1968).

↩ -

4

The Citizen Kane Book (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1971).

↩ -

5

Cukor’s essay is reprinted in Richard Koszarski, ed., Hollywood Directors 1914-1940 (Oxford University Press, 1976).

↩