In response to:

Veritas at Harvard from the April 28, 1977 issue

To the Editors:

I am surprised that in his “review” (NYR, April 28) of material contained on less than one page of my 278-page essay “Political Controversies at Harvard, 1636-1974,” in Education and Politics at Harvard, by David Riesman and myself, Sigmund Diamond charges that I dealt with the way he was treated at Harvard as a “deviant case” to Harvard’s proud record of defending academic freedom during the McCarthy period, and that by not detailing the story I covered up Harvard’s behavior in his case.

I would note that far from covering up Harvard’s role, my article was the first one published anywhere which challenged Harvard’s self-image as the heroic defender of academic freedom against congressional and other extramural onslaughts. Not only was I the first to ever mention in print what happened to Diamond and two others, but I also discussed for the first time anywhere the case of Stuart Hughes who was pressed to resign as associate director of the Harvard Russian Research Center for his involvement in the Henry Wallace campaign. As for the Harvard faculty, I reported a poll taken in the spring of 1949 in which the “professors voted by two to one against Communists on the faculty, while the students cast a similar large majority in favor of the academic rights of Communist party members…. Men present at Harvard at the time recall that the faculty support for the rights of Communists to serve as teachers appeared to come largely from the ranks of the younger non-tenured staff.” So much for my cover-up of Harvard’s heroic record of resistance.

Why did I not go into detail in analyzing what happened to Professor Diamond and other colleagues? The answer is very simple: I assumed that neither he nor others (one of whom has since died) wanted their past relationships to the Communist Party discussed publicly. In Professor Diamond’s case I had very good reason to so believe for I had been informed by a mutual friend, in the context of telling me a great deal about the episode, that for many years Diamond had withheld all information about his political past and the Harvard events from his own children. Before I began working on this essay, I twice had occasion to talk to Professor Diamond about what happened to him at Harvard, once at some length, and somewhat obtusely as it now seems, I received the impression that he did not want his past political associations known publicly. Subsequent to the publication of my essay, two years ago, I learned that Professor Diamond was annoyed at the fact that I had not gone into detail about his case, particularly with regard to the role of McGeorge Bundy. Consequently, in a recent article, this one an as yet unpublished essay on the Columbia Sociology Department, which Professor Diamond himself can attest was written before I knew of the existence of his “review” for your journal, I wrote about his treatment for a second time.

In that article which is very short and is a personal recounting of events which occurred during my stay at Columbia as graduate student and faculty member, I reported that, “during the end of my stay at Columbia, the department unanimously nominated Sigmund Diamond to be an assistant professor of sociology. Diamond had been notified by McGeorge Bundy, the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, that Harvard would not back him up in his intended refusal to testify before Congressional Committees about Communist activities. Diamond, who had broken with the Communist Party, had voluntarily told the Dean of his past affiliations. I had learned of Diamond’s situation from friends at Harvard and I suggested him for a post in Sociology, since the department was looking for a historical sociologist, and Diamond’s doctoral dissertation, later published as a book, was basically a sociological work dealing with the changing image of the American businessman. To my recollection and knowledge, no one in the department voiced any concern about the possible ramifications of the fact that Diamond might gain publicity as a recalcitrant witness, and the Columbia administration, also informed of Diamond’s past, confirmed his appointment. Diamond, in fact, was never called before any Committee of the Congress.”

To conclude, I remain puzzled as to why I should be accused of a “cover-up,” when I was the first person to ever expose in print the contradiction between Harvard’s words and actions in this and a number of other cases, while Professor Diamond remained totally silent for well over two decades, and then two years after the first public presentation of what happened to him and others finally went public. Professor Diamond could not understand that the constraints on my report lay in my desire to let people know the main gist of what Harvard did—namely to fire non-tenured persons, or withdraw appointments for political action or positions—while protecting him and others. Professor Diamond, better than most people, should have understood why someone chose not to name names and following up the logic of that decision could not go into great detail.

Seymour Martin Lipset

Stanford University

Stanford, California

Sigmund Diamond replies:

In a letter of five paragraphs Professor Lipset uses the word cover-up four times. Once the word is placed in quotation marks, as if it were being quoted from my article; once he says that “Sigmund Diamond charges” that Lipset “covered up Harvard’s behavior in his case”; in his concluding paragraph he is “puzzled as to why” he “should be accused of a ‘cover-up’….” Nowhere in my article in The New York Review do I use the word “cover-up.” If Professor Lipset feels compelled to deny the charge of cover-up, he is responding to an indictment I never made. I wrote about his analysis, not his motives.

Professor Lipset is disturbed that my article deals with “material contained on less than one page” of his 278-page essay. As to that he is right. The McCarthy period was a major event in the history of academic freedom at Harvard, and it seemed to me that Lipset’s essay was seriously flawed in its treatment of that episode. In my article I raised a number of questions about Harvard’s policy during that period, questions that Professor Lipset did not raise; inquiry into those questions casts doubt on the Harvard administration’s explanation of its own behavior and makes Lipset’s account bland and complacent. Professor Lipset seems to be suggesting that it is unfair to make so much of a matter that is dealt with in less than one page of a 278-page essay. Surely he must understand that the issue is the adequacy of his treatment. It was Professor Lipset’s obligation as a scholar to inquire into the cases he merely mentions. He did not do so; therefore I did. Only to mention those cases, as Professor Lipset did, is disarming; it suggests scholarly analysis without providing that analysis and leads the reader to believe that the matter has been dealt with. Lipset’s treatment of the episode in the book is insufficient; so is his present statement.

Professor Lipset claimed to know of three cases. Why didn’t he investigate them? Because, he tells us, he “assumed” that neither I nor the others wanted our past relationship to the Communist Party discussed publicly; I, “better than most people, should have understood why someone chose not to name names and following up the logic of that decision could not go into great detail.” In short, it was to protect me and others that he showed such restraint.

But to name names is one thing; to discuss cases is quite another. Professor Lipset is a member of a profession in which it is a standard practice to protect the anonymity of informants and even of the site of one’s research. Muncie, Indiana, becomes Middletown; Newburyport, Massachusetts, becomes Yankee City; particular people become A, B, or C or are referred to by generic names. Not mentioning names does not prevent questions from being asked or the story from being told.

Professor Lipset “learned” that I was particularly annoyed that he had not gone into “the role of McGeorge Bundy.” He did not learn that from me. In any case, why should his desire to protect the victims lead him to protect the anonymity of the victimizer? From what did Mr. Bundy need to be protected? Professor Lipset either preserves Mr. Bundy’s anonymity or reveals his identity when it suits him. He concludes his book ringingly:

…as McGeorge Bundy once explained of Harvard “the extraordinary freedom…was sustained…more by the universal commitment to the ideal of excellence,” than by anything else. The price of freedom and innovation is often disturbing; the rewards are very high. In February-March 1971, the International Gallup Poll asked leaders in 70 nations: “What university do you regard as the best in the world—all things taken in consideration?” The poll reported that Harvard topped the list.

Nor do I think it sufficient for Lipset to say that he “assumed” I would not want to be mentioned publicly. It was his obligation as a scholar to find out if his assumption was valid.

In his letter to The New York Review Professor Lipset quotes from an as yet unpublished essay dealing with the Sociology Department at Columbia University. He says in the brief excerpt he quotes that: (1) I had been notified by Bundy that “Harvard would not back [me] up in [my] intended refusal to testify before Congressional Committees about Communist activities”; (2) he suggested me for a post in the Columbia Sociology Department because he had heard of my situation “from friends at Harvard.” I received a copy of that unpublished essay from Professor Lipset on March 28, 1977; on March 29 I wrote to him saying that “there is a world of difference” between not supporting me in my decision not to inform and requiring that I name names as a condition of employment. Though I wrote him that “I had never heard until I read your MS of your having suggested me for the position at Columbia” and pointed out that Professor Paul F. Lazarsfeld had interviewed me for a possible position at Columbia before I had been dismissed at Harvard, I also said that I wanted “to take this occasion to thank you for having done whatever you did to help bring me to Columbia.” On April 8, 1977, in a letter to me acknowledging what he called his relatively minor role in the Columbia job offer, Professor Lipset asked if he might publish a corrected version of the account. The sentences he now quotes are unchanged from the version he originally sent me.

Two minor points:

(1) I have no memory of having talked to Professor Lipset about this situation on any occasion prior to the publication of his book. How could he have so misconstrued the situation at Harvard if we had talked? In two letters Professor Lipset has sent to me since the publication of my New York Review article, he makes no mention of his having talked to me about the situation at any time. I did not know he was writing a book on the subject until I saw it in print.

(2) It is true that I “withheld” information about these matters “for many years” from my “own children.” In 1954, when the episode at Harvard occurred, my children were eight and six years old.

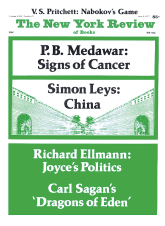

This Issue

June 9, 1977