In response to:

The Party Isn't Over from the June 15, 1978 issue

To the Editors:

Like most of his writing, Carry Wills’s “The Party isn’t Over” (NYR, June 15) is enjoyable and suggestive. His remarks on the nature of television’s importance to American politics are penetrating. He is also on solid ground in his portrayal of much of what Henry Fuirlie says in The Parties: Republicans and Democrats in this Century as nonsense.

Unfortunately, however. Mr. Wills’s eye for political misinterpretation seems hyperopic. He rightly takes Mr. Fairlic to task for reducing the South to “the-blacks, the farmers, and the rednecks.” Yet earlier in the same sentence Wills himself had reduced the white South to one category: “rednecks.” That President Carter narrowly lost the white Southern vote does not necessarily mean that he lost the “rednecks.” Contrary to popular belief, some whites in this region shade the area below their hairlines with collars, white, blue, or polkadat, Perhaps some of these whitenecks voted for Gerald Ford.

Mr. Wills’s analysis ignores two critical points: 1) to win the South it is no longer necessary to carry a majority of white voters: and 2) the South is no longer “the single largest homogeneous block of voters” in the nation. That distinction belongs to the Mountain West, with its increasingly conservative Republican representation in Congress. For several years the trend in the South has been away from the traditional racist, reactionary militarists who, with good cause, strike fear in Mr. Wills’s heart.

The significance of the 1976 Election was not that Jimmy Carter failed to win the votes of a majority of whites in the South, but that a large minority of Southern whites voted with blacks to form a new—albeit shaky—Southern Democratic majority. The poor which farmers that Mr. Wills is so quick to dismiss were an essential part of Carter’s winning margin. Carter carried the rural, predominantly white counties in most of the South.

As I have argued elsewhere (intellect, April 1978), the 1976 Election marked the South’s rejoining the union. Long solidly Democratic, more recently solidly anti-Democratic, the South censed to be solid in 1976. Instead, it spilt along economic lines much as the rest of the nation had been doing since the 1930s. Well-to-do and middle-class whites voted Republican, while the less affluent among both races tended to support Carter.

As Mr. Carter is learning, this neopopuliss coalition is even more difficult to hold together in office than it was to create in the campaign. But that fact should not be allowed to obscure the significance of building the alliance in the first place.

A final question must be raised about the Wills article. He says that “civil rights played no part in (Truman’s) famous upset” victory in 1948. It is certainly true that President Truman opposed the civil rights plank (despite his later attempt, in his memoirs, to take credit for it), but civil rights proved to be crucial in the campaign. Without the support of blacks and white liberals (many of whom would likely have voted for Henry Wallace or stayed home had the civil rights plank been rejected). Truman would have lost Ohio, California, and Illinois…and the election. Clark Clifford may have been a false prophet in assuring Truman that there would be no Southern spilt, but he was absolutely right in stressing the need for a statement on civil rights to head off the Wallace threat. The ADA. Hubert Humphrey, and other liberals forced victory on Truman against his will.

Mr. Wills goes on to say that Strom Thurmond’s 1948 Dixiecrat threat was vindicated twenty years later. This, too, is wide of the mark. What 1948 showed the Democrats was that they could win without the solid South. (Truman did have a nearly solid West, however, a blessing no Democrat is likely to enjoy in the near future.) A quick recollection of the situation a decade ago may bring to mind the fact that a war was going on and Humphrey was defeated because of it, not because of George Wallace, Indeed, Humphrey came within a few days of winning despite the war and the Wallace candidacy.

None of which is to deny Mr. Wills’s main thrust, that the Carter coalition is unstable. So it has always been for the Democratic majority since 1932. But the division of the South into two groups of roughly equal size should be seen as an aid, not a problem, for the Democratic party. It is far better to have a chance in win the votes of the South by a narrow margin composed of most blacks and less than half the whites than to concede the region, which had been the practice of the party from 1964 to 1976.

Robert S. McElvaine

Department of History

Millsaps College

Jackson, Mississippi

Garry Wills replies:

- How can I be ignoring the critical point that “to win the South, it is no longer necessary to carry a majority of white voters” when my whole argument rested on the fact that Carter did just that?

- The “mountain West”—sixteen states then went Republican in 1976—gave Ford 130 electoral votes. Over a third of that (45) came from one volatile state, California. The rest of the votes were scattered over territory hard to deal with in terms of TV money and a candidate’s time (three of the sixteen have only three electoral votes, five have four. Tiny New England’s six states have a vote equal to that of ten much larger Western states). By contrast, just twelve Southern states gave Carter 139 votes—over half those needed for election. This is still the key bloc in presidential elections—as it was in 1980. when Kennedy, using Johnson’s South as an electoral base, beat Nixon who carried fifteen mountain West states. Nixon could only win, in 1968, when Wallace denied the Democrats half the Southern states and Thurmond gave the rest to Nixon.

-

I do not reduce the South to one category after saying that even three do not embrace it. My argument was a fortlori: if Carter lost the overall white vote, clearly he lost the racial vote.

-

Anyone who thinks Wallace remained a threat to Truman by election time in 1948 must have expected McGovern to win by a landslide in 1972.

-

What 1948 showed was that the Democrats could win without part of the South, if that part did not go Republican—but, in 1968, it did go Republican.

Hyperopia remains, I believe, the distinction of Millsaps.

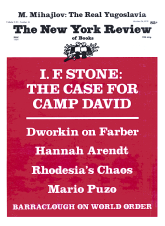

This Issue

October 26, 1978