When it comes to contemporary studies of the human brain, Professor J.Z. Young is in the position of the Master in the famous Balliol Masque. “First come I, my name is Jowett. If it’s knowledge then I know it.” The book which he has now published is based upon the series of Gifford lectures which Professor Young delivered in 1975-1977 at the University of Aberdeen. A condition of Lord Gifford’s nineteenth-century bequest to the four main Scottish universities, which still serves to endow these lectures, was that they be devoted either to ethics or to natural theology, but with the passage of time and the waning of interest, if not in moral theory, at least in the claims of natural theology, this condition has come to be very laxly interpreted.

In Professor Young’s case, moral theory figures only in the form of a mild obeisance to aesthetic and spiritual values and in the insistence that man is programmed to be a social animal. Neither is anything said about natural theology. Professor Young is too tactful to make an explicit profession of atheism, though he does speak at one point of its being “degrading to use detailed beliefs that have become inconsistent with knowledge.” It is, however, clear that he does not regard the knowledge which he has acquired about the workings of the brain as lending any support to the notion of a divine creator. At the same time he shows respect for religion as a social institution and displays what one may fairly call a religious attitude toward life itself. There is also a shadow of the argument from design, in that the terms in which he speaks about the brain, and indeed about the human body as a whole, are uncompromisingly teleological.

In my frivolous comparison of Professor Young to Dr. Jowett, I meant only to stress his mastery of his subject, not at all to suggest that he comes forward as a pundit or that he overestimates the extent of his knowledge. On the contrary. One of the most impressive features of this book is its modesty, as expressed not only in the reluctance of the author to go beyond his evidence, but in his recognition of the enormous amount of work that remains to be done before the anatomist can match the assurance of the physicist in putting forward even statistical laws. For example, there is still no established theory about so fundamental a question as that of the neural base of human memory, though Professor Young develops a convincing set of arguments for holding that a memory record is established not, as has been suggested, by a change of some specific chemical molecules, but rather by a change in the pathways between neurons within the nervous system.

Let us suppose that this is the right answer. We still need to account for the distinction between short- and long-term memories: we still need to explain the very great variations in the capacities of different persons to retain both skills and recollections of events. It still remains doubtful whether forgetting can be put down merely to the interference of subsequent learning. Professor Young has views on all these questions, but the experimental evidence allows them to be no more than tentative. Much of the evidence that there is derives from his own protracted series of experiments on the brains of octopuses, which supply what he has shown to be a fruitful analogy. He can say with confidence that “human beings, like octopuses, have the power to continue to learn the symbolic significance of external signals, even when they are adult,” but has to admit that the exact nature of the changes in the nervous system that makes this possible remains unknown.

It is not only that the relative lack of opportunity to experiment on human beings has made it more difficult for biologists than physicists to arrive at specific causal laws. This difficulty, in Professor Young’s view, resides in the very nature of his subject. He points out that if a principle of determinary reigned in chemistry it would have to imply that “given stated initial conditions a particular chemical reaction will always follow a particular course.” But biology stumbles at the first hurdle of generalizing a set of initial conditions. For “the essential feature of each living organism is its history, und this is at least partly unknown, moreover each animal consists of a great number of parts, all different and all changing rapidly.” Neither is it just a matter of excessive complexity. As Young sees it, a condition of living is the making of choices, and it is this factor of choice that limits the possibility of making precise forecasts of human or Indeed animal behavior. “There is,” he says.

Advertisement

nothing peculiar about the Individual chemical components of a living system but no two organisms contain precisely the same set of them. Every creature begins with an endowment of varied possible actions. We can never be sure what these are because they are continually subject to mutation so that the genetle make-up of an organism cannot be known with the same “certainty” as the composition of a chemical substance.

And then there is the historical factor. Different individuals experience different events and adjust their behavior to them. There is, however, a pattern which underlies these differences. The behavior varies according to the circumstances, but it is focused upon a common target. The aim of all living organisms “is to maintain the constancy of their internal environment,” and to do so in an external world to which they have continually to adapt themselves if they are to maintain their organization and so fulfill their primary urge to live. It is this need for adaptation that both illustrates and transforms the possibilities of choice. As Young puts it.

Selection has brought our ancestors from the pre-biotic soup first into single cells then through many stages to fishes, newts, reptiles, carly shrew-like mammals and on to monkeys, apos, and early man.

He implies that none of these stages is wholly without its present effect.

Young is not, however, primarily concerned with expounding the theory of natural selection. His interest lies rather in the mechanisms by which living things maintain their organization, and the originality of his treatment of this question consists in the thoroughgoing extent to which he is prepared to treat it as semantic. “We cannot repeat too often,” he says, “that the center of all our problems is the study of codes, signs, and languages.”

The idea of the genes as transmitting information has been familiar at least since the discovery of the structure and function of the DNA molecule. The instructions needed to make the proteins of every type of cell in the body are said to be encoded in the nucleus of the fertilized egg. This inherited program, which is “transcribed and translated during development and throughout life to produce the living individual,” is the first of what Young terms “the languages of life.” The second “language,” which all mammals possess, is to be found in the structure of the brain. Its units are groups of nerve cells, amounting in the human brain to more than 50,000 million in number and varying in type, and its syntax consists in the ways that these groups are organized and their relations to one another. In the case of human beings. Young lists two further languages, again described as “programs,” the first being “speech and culture…largely embodied in the organized sounds of spoken language” and the second that which finds its expression in “writing and other forms of recorded speech,” thereby enabling vital information to be stored outside the body of any actual individual.

Though it may seem a little odd to speak of a language as being itself a program, rather than as the means by which a program is formulated, there is nothing very questionable about Young’s use of the term in the second païr of cases that he lists. In these cases we have to do with systems of signs to which persons attach sense and sometimes reference, in accordance with syntactic and semantic rules. There are many problems, yet to be solved, concerning both sense and reference, and the relation between them, but there is no doubt that these problems fall within the domain of the philosophy of language. Does this domain extend, or is it profitable to extend it, to the problems concerning the genetic endowment and the cerebral operations of mammals of all types? I have to say that I do not find this altogether clear.

Let us return to the DNA molecules. According to Young, “they give us what we can only call instructions and information, providing standards indicating what to do.” But information needs to be interpreted. If instructions are to be carried out, except by accident, they need to be understood. What agency performs this task? If it is the brain how does it communicate with the cells where the proteins are made? Is there anything more to the facts than that the structure of the genes is inherited and that a correlation has been discovered between the structure of the genes and the development of the bodily cells? In short, is the reference in this context to the deciphering of a code not simply metaphorical? There is nothing objectionable in the employment of metaphor; especially if it serves to further understanding. The question is whether the model of the diffusion of information is really more enlightening than more humdrum talk of causal dependence.

Advertisement

I have a similar query about the way in which Young formulates his teleological standpoint, without at all wishing to dispute the grounds on which it is based. Thus, early in the book, he cites the example of the bacterium Escherichia coli, which lives in our intestines. It has been found that if a culture of these bacterin, living in a glucose solution which supplies them with their energy, is given the sugar lactose, they will begin to produce the enzyme ß-galactosidase, not previously present but required by them if they are to draw energy from the lactose. They thereby serve the needs of our intestines which have to be disposed to deal with whatever sort of sugar is sent down to them.

Young’s way of describing this process is to talk of the arrival of the new sugar as being “detected” by some sensory system at the surface of the cell, of a “signal” being passed through the cell, of the liberation of genes which have been “held suppressed” while they were not in use, and of the bacteria as “selecting” from the enzymes at their disposal those that “transcribe” the sequences such that ß-gulatosidase is produced. Instead of attributing to the bacteria these anthropomorphic powers of detection, signaling, suppression, and choice, would It not be simpler and equally just to the facts to speak of a series of changes, constituting a regular causal sequence? The teleological point could still be made by remarking that these sequences fitted into a pattern such that while their elements varied according to the attendant circumstances they always had the supply of energy as their terminal result.

When it comes to the language of the brain, Young’s exposition is not always easy to follow. Our brain cells are said to provide the codes in which are written both a set of hypotheses about what is likely to happen and a set of programs for dealing with these contingencies. Presumably the brain also carries out the decoding which too is necessary if the appropriate actions are to be initiated. The hypotheses are at least partly based on information obtained through the senses and here it is the cortex that acts as the interpreter.

The cortex [as Young describes it] is an immense folded sheet of layers of nerve cells, arranged in columns. The nerve fibres bringing signals from the sense organs, via the thalamus, enter the sheet from the inside. They are arranged in a regular pattern or map, which exactly reproduces every point of the receptive surface of the body…, in the correct relations with its neighbors.

There are cortical maps for vision, hearing, and touch but not for smell or taste. In the case of vision, the map is vastly enlarged. In the primary visual cortex, situated at the back of the head, “there are 5,000 cortical cells for each cell of the thalamus, which sends on the signals from the optic nerve.” And beyond this primary area there is a series of secondary areas each carrying its map of the retina and having cells with distinctive functions; for example, in some areas there are cells sensitive only to one color.

So far, so good. But even maps have to be interpreted. The mere fact that two objects are similar does not render one a sign of the other. The main difficulty that I find in Young’s account is that he has next to nothing to say about consciousness. At one point he refers approvingly to Ryle’s dismissal of the mind as “the ghost in the machine.” But much as Ryle achieved, it has since been shown that his version of logical behaviorism is not wholly adequate to its purpose. Perhaps Young would be prepared to rally to the current theory, which represents so-called mental states as being factually identical with states of the brain. But he does not advance any arguments in favor of this theory or consider the objections which have been brought against it.

This omission does not detract from the wealth of information which the book contains. I was especially fascinated by the description of the results of dividing the corpus callosum, which separates the brain’s two hemispheres; an operation which is carried out to prevent the sprend of epileptie fits. Following this operation only what is seen with the right eye can be described verbally since for the most part only the left cortex, which receives signals from the right eye, supplies the capacity for speech. But if the right hemisphere cannot produce speech, it can exhibit understanding. The left hand, which the right hemisphere controls, can obey an instruction to pick out some object, to which the verbal comments, issuing from the left hemisphere, are not appropriate. If different pictures are shown to the two eyes, only those seen by the right eye can be named but the utterance may be accompanied by a display of emotion which fits a picture shown to the left eye. The source of the emotion will not, however, be acknowledged.

This is only one of the many examples which make it right to say that even if there are serious philosophical problems which Young has failed to solve, he has provided abundant material which should greatly assist in their solution.

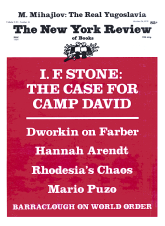

This Issue

October 26, 1978