1.

Finche ch’e la morta, ch’e la speranza.

—Lampedusa, Il Gattopardo

So long as there is death, there is hope? That is a sentiment so singular and so rooted to its place of origin that, if you found it upon a shard in the farthest desert, you could guess that someone had tarried there who had spent most of his life in Sicily.

There is no part of Sicily less Sicilian than Ortygia, the last extremity of its southeast corner. It is all the flower and none of the thorn. And yet nowhere else does the odd notion of death as man’s last best hope press a stronger claim. For here is the most wonderful city that any of us is ever likely to see and a great piece of its wonder is that it is dying.

Ortygia is the island fortress of the old Greek Syracuse from which the new Syracuse has fled. In its abandonment it cries out to the portion of us all that cherishes its fellow creatures and deplores their aspirations. It achingly and joyously reminds us that the blessings of the modern arrive in the company of two curses: nothing speeds decay like progress and nothing preserves except neglect.

Aeschylus staged The Persians in Syracuse. The tyrant Dionysius called Plato here as instructor in the arts of government and repaid him with so valuable a lesson in the nature of governors that only an unceremonious debarkation for Athens saved him from sale into slavery. Pindar was inspired and Cicero edified here. Archimedes glared across these seas and employed their sun and his mirror to set Roman ships afire. Syracuse had broken Athens and sent the Carthaginians limping away; and, this time round, she and Archimedes came close to beating back Rome herself.

The Syracusans were moderate in their moments of aggression and implacable in their hours of resistance. Ortygia has been violated again and again, and always it has outworn its conquerors and restored its own inviolable self. And always, when the Syracusans turned at bay, their last asylum was this little island a hundred feet from their mainland.

Naturally then, the huge and formerly swarming Hotel des Etrangers stands empty, the once-arrogant crimson of its facade paled and chastened by the sun. The tourists are no longer a force in occupation; dying, Ortygia has outlived the last of its barbarian invasions.

The grandeur of the names in this great history seems rather beside the point now, because Ortygia owes so much of its command over the sensibilities for being a monument to anonymous artisans. By no means the smallest of its charms is the refuge it affords from distraction by certified masterpieces.

Aside from its Greek coins, Syracuse possesses only two works eligible for notice in college surveys of the history of art. They are the Venus Anadiomene, which could dangerously ignite the libido of a Capuchin who had lain for a century dead, and the ravaged Annunciation of Antonello da Messina. And, with perfect tact, Syracuse has spared the visitor the perturbations of awe by sending both on voyage, the Venus to Canada and the Antonello on a ramble about Sicily before being dispatched to America as part of the exhibition of a master whose work, since Sicily is the sport of foreign conquerors and alien tastes, seems far more Flemish than Italianate.

We must then happily make do with the comfortable companionship of masons and stone carvers whose names long ago were mixed into the dust toward which their buildings are exquisitely sinking. Few of them were allowed the pretension of calling themselves architects; Luciano Ali, who designed the superb Benevantano del Bosco palace, is identified merely as “a local master mason.” Still he has left a name that has endured for two centuries, and that is a distinction unique for his class and his kind. The workmen who rebuilt Ortygia after the 1693 earthquake are otherwise almost all unknown gods; and yet they have left everywhere behind them the mark of their pride of craft and their recognition of the law that cities live or die according to the opportunities they offer to those who glory in work. Ortygia never erected a palace for some Spanish proprietor without reserving its ground floor for the shops of artisans.

All those artisans are gone now and they have left no descendants, because it has been more than a century since Ortygia has had any function except to enchant the beholder and stifle the inhabitant. The Church of Rome was its last major employer; when the eighteenth century ended, this island that a laggardly wayfarer can walk all the way around in forty minutes held twenty-two parish churches, fifteen monasteries, and eleven convents.

In 1861, the new and anticlerical kingdom of Italy nationalized the monastic properties; and this triumph over superstition was followed by one of those cataclysms for the life spirit that serve to teach even the most radical temperament that it cannot keep touch with reality unless it keeps a few reactionary ideas firmly in place.

Advertisement

The monasteries had been the chief labor market for Ortygia’s lay population; and, as they declined, there was less and less use for the old skills, and the old craftsmen left when they could or withered away when they stayed. Ortygia has quarters that have lost three-fifths of their population in the last fifteen years; and, in a while, there will be no one living there except those who would rather live anywhere else if poverty had not stranded them in warrens so tortuous that appellations like via for street and vicolo for alley are inadequate to describe the extreme limits of their constriction. Ortygia’s street plan is singular for needing recourse to the word rione to designate passageways that are too narrow for the shoulders of any National Football League linebacker.

To wander past the all-but-empty palaces and to peer through the poor garments hung out to dry in the fifteenth-century courtyards of this bleached, airless but still most seigneurial of slums is to reflect how hateful to the dweller a place so lovable to the visitor must truly be and to understand that the flight to the salmon-colored cement blocks of modern Syracuse across the bridge has been the desertion of poetry in the cause of common sense.

From time to time, over the last hundred years, one or another cloud conqueror has given way to the vision of dragging Ortygia into the modern age, if only to the extent of renaming its streets Via Cavour or Via Nizza or Via Vittorio Veneto or Via Trieste, as though its inhabitants might feel at one with a greater Italy if they walked past signs affirming their community with personages and places so distant from themselves as to seem inscriptions in some foreign tongue.

The Italy of fascism undertook the last of these ventures into salvation by destruction; and its scars survive in the terrible swarth where Benito Mussolini’s engineers made hecatombs of palazzi to create an avenue fit for the local branches of Alitalia and UPIM, the department-store chain. It is only one more instance of Ortygia’s endless capacity for absorption that this Corso Littorio, the name Mussolini chose to celebrate his newest battleship, is now called Corso Matteoti as a tribute to the socialist parliamentarian murdered by the fascists.

Post-Mussolini Italy has been uniformly subject to the ministrations of governments with a philosophical commitment to leaving bad enough alone; and they have been conscientious about resisting most temptations to rescue Ortygia.

2.

Whatever is new on Ortygia’s walls is most often a reminder of death. When a soul departs, those it has left behind signify their sorrows with broadsheets plastered about the streets or, in the cases of more penurious circumstance, notepaper-sized placards on the doors of the bereaved. They run from the humble (“My Dear Husband”) to the grand (“The Marchesa Ada Gardella de Castel Lentini, 26 May, in Rome”). Of course: marchesi may give up the ghost in quite dreadful ambiences; but they don’t die in birthplaces the world has since forgotten.

Occasionally an eminence passes who is more locally familiar, and then the walls flower with memorial testaments: “The Communists of Syracuse remember the intense social and civic involvement of Comrade the Attorney Salvatore Di Giovanni,” And right next to that affirmation of a faith that has no need for God, the wife, the sons, and the daughter of this deceased Bolshevik have certified a more intimate grief on a placard bordered with lilies and crowned with the head of Christ in thorns. Sicilians are Italian only for being part of a shared community of divided souls.

One day there was a new sheet on the walls and, for once, it had to do with life, if only, Ortygia being Ortygia, with life whose liveliest claim is upon the historical memory: the next offering of the Syracuse Tourist Agency’s cultural program would be a concert by the Romano Mussolini Quintet.

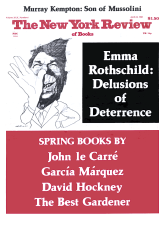

Romano Mussolini is the third and youngest son of fascism’s founder. He was, one has to think, more the fruit of policy than of passion, since Mussolini was obsessed with the acceleration of Italy’s birthrate and felt it a leader’s duty to teach by example.

Romano Mussolini was only thirteen when his father lurched into the Second World War; and, in less than three years, his family was expelled from the Rome that had felt complimented to leave its name at his christening font. His public debut as a jazz pianist returned him to transient notice twentyfive years ago; but it did not seem a career option that held much promise or was worth much attention. He had come old to his apprenticeship and had brought there a taste even more obsolescent than his name; when he began, by all accounts, time had stopped for him where it did for the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, somewhere in 1925 in the exhausted vein of “Tin Roof Blues” and “The Original Dixieland OneStep.” Still Syracuse is the attic of the world; and there could not have been conceived a more proper place to find one of history’s discards at work on a selection of jazz’s.

Advertisement

The visitor was then drawn across the bridge to mainland Syracuse’s archaeological park by the same irresistibly unsavory impulse that used to carry the crowds to watch Lola Montez in her cage or Joe Louis at Caesar’s Place; and nothing could have been less to be imagined than to have this discreditable pilgrimage end with the discovery of a piece of flesh that is Italy’s only inarguable repudiation of every vestige of the fascist spirit.

The stage had been lit for the Mussolini Quintet in the open-air amphitheater whose vegetation has immured and softened most traces of tyrants dead twenty centuries ago. Romano Mussolini would play with his back to the altar of Hieron II, a pile of stones no longer capable of evoking their original function, which is just as well, because Hieron, an otherwise temperate ruler, was accustomed to celebrating his and Syracuse’s prosperity with the annual sacrifice to Zeus of upward of 450 oxen there. The conjunction of relics of despots, varyingly benevolent, and 2,200 years apart, could have served to inspire fashionably ironic reflections if Romano Mussolini had not so startlingly turned out to have nothing whatsoever to do with that sort of thing. He was found at the soda wagon beside the gate, drinking a can of the orange pop called Fante. Fante is also the Italian word for “infantryman,” and there can still be seen in Palermo a fascist construction flourishing Benito Mussolini’s slogan: “The fante is the bud and victory is the flower.”

Romano Mussolini has let his figure go most agreeably, and his countenance is rubicund, humorous, and forever immune to his father’s itch for the display of the self as counterfeit of iron. The peaceful and the pleasant sat upon him as comfortably as the old coat over his shoulders. Somewhere back on the road, his mother’s genes had expelled his father’s; and here was the proof of her victory.

He had, he said, found his path when he was a little boy, and his inspiration had been his brother Vittorio, who is ten years older. “My brother,” he remembered, “was one of Italy’s first jazz critics. He used to contribute articles to the university reviews. I was only ten when he gave me a big picture of Duke Ellington.”

Most of what his visitor had known about Vittorio Mussolini before then had been that he had been a pilot in the Ethiopian war and that, afterward, he had published a reminiscence that included this image:

One group of cavalrymen gave me the impression of a budding rose unfolding as the bomb fell in their midst and blew them up.

But now it had become possible to wonder whether some fascist hack had not conjured up this atrocious picture and whether Vittorio Mussolini had not just signed without reading it, and turned back to Jelly Roll Morton. The brothers Mussolini were coming to sound like children whose tastes were enough better than their father’s as to make them fortunate that he came home too seldom to notice where their minds were tending.

Suddenly there arose the fantasy of some secret life of fascism in its terminal writhings: the Anglo-American fleet lowering upon the southern coast of Sicily, and, in Rome, at the Villa Torlonia, Benito Mussolini upstairs abed under assault by his ulcers and intimations that it might all be coming apart, and downstairs little Romano listening to Count Basie on the American Armed Forces Radio and rejoicing that its signal was growing louder and louder.

“Duke Ellington came to see me in 1950, the first time he got to Rome after the war.” There have been better years than 1950 to be a Mussolini in Italy; and his recital of that memory summoned up all his loneliness and the renewed recognition that, in Duke Ellington, America had raised up its only purely perfect gentleman.

Then it was time for Romano Mussolini to go about his business and he set to arranging the microphones. There was no telling him from any other workingman who, having taken his ease, is now about to return to the task he loves. If only for a little while, the spirit of its ancient artisans had come back to the neighborhood of Ortygia. After which, there occurred as the ultimate surprise the revelation that Romano Mussolini is a very good workman indeed. There were barriers to the fullest expression of his best, to be sure; his drummer and his trombonist are both Argentine imports and, to speak as kindly as possible, rather too stuck in the primeval, the one too clumsily intrusive in any vein except the Afro-Cuban, and the other too much the victim of what Henry James once called “the demoralizing influence of lavish opportunity,” in this case the open horn.

But there arrived occasions even so when Romano Mussolini worked alone with Julius Farmer, his contrabassist, and only then could there be heard vivid suggestions of high possibility.

Julius Farmer is twenty-eight and was born in New Orleans, a city that Romano Mussolini cites as the founding capital of a vast territory with the same fervor that his father brought to his invocations of imperial Rome. But Farmer does not work in the New Orleans tradition; his line is like Tommy Potter’s or Curly Russell’s, lean, spare, and thrifty of notes.

When their companions rested from their clutter, bass and piano worked alone with the entire intimacy that is the particular marvel of jazz; and there came a moment on Ellington’s “A Train” when Romano Mussolini left Julius Farmer on his own and sat there, his fingers off the keys, looking at the soloist as though this young man had some secret that he himself proposed to go to his grave pursuing, and as though this was one of those nights that bring the belief that some day he will find it.

The Mussolini family’s African empire had shrunk down to one young black American, and that one not subject but comrade. Trajan’s legions could hardly ever have marched across richer possessions than those these two were sharing then.

Near the close Romano Mussolini confessed himself so happy that he could not resist singing, and he stood up and hoarsely chanted that most dignified statement of emancipation from all forms of false pride: “All right, hokay, you win. Honey honey come back to me.”

Between whiles, he explained the music, and told jovial anecdotes about life on the road, and held a contest with a free record as prize for the first scholar to name the composer of “Honeysuckle Rose.” By then there was the most honest sweat upon his forehead and the dark blue tails of his sport shirt had worked their way free of his trouser belt and he was talking beguilingly with his hands.

He was the incarnation of all the Italy his father had tried to harden into something fierce and stern; when Benito Mussolini sought an adjective to describe the sort of Italian who most roused his contempt, he settled for “picturesque”; and that is just what his son Romano is and no less serious a man for it.

Afterward his visitor remarked, by no means insincerely, that he had detected echoes of Art Tatum in the style. “Magari,” Romano Mussolini replied. Magari is an all-purpose Italian word which the dictionaries define as meaning both “maybe” and “even,” and then collapse in despair before the whole spectrum of its nuances. In this instance, we may take magari to have meant, “If only….” His father’s dream was to be Julius Caesar; and his is to approach, in time, the level of a blind, black piano player. We old men are wrong: taste does not necessarily deteriorate from generation to generation.

History has set Benito Mussolini down as an inattentive parent. And that may have been the best gift he could have given his children; how otherwise could he have left behind a son this utterly unfascist? Ortygia turned out, after all, to be the most appropriate of places to come upon Romano Mussolini. They are both splendid examples of the sovereign uses of neglect.

This Issue

April 14, 1983