In response to:

'Invitation to an Inquest': An Exchange from the September 29, 1983 issue

To the Editors:

In the Schneir-Radosh exchange on the Rosenberg case [NYR, Sept. 29], I’m mentioned as one of three ex-Communists who denied telling Ronald Radosh what he attributed to us in his book, The Rosenberg File (co-authored by Joyce Milton).

I have so denied, emphatically and outraged. Both in the book and in his NYR exchange with the Schneirs, Radosh attributes to me the opposite of what I told him. He declares, in the exchange: “Max Gordon gave us background on how Communists in general who had been recruited for spying were handled by the American CP.” In the book, he quotes me directly as saying that anyone who became a Soviet spy was separated from the Party.

What is the actual fact? Radosh called me some five years ago, as a friend I thought, to ask if I knew anything about the Rosenbergs. He indicated he was preparing an article, as I recall it, marking the 25th anniversary of the execution; no mention was made of an interview for a book. I replied that I knew nothing of the Rosenbergs and had not heard of them before their arrest in 1950. To a more general question about party policy concerning separation of spies from membership, I responded that I had never heard of any association of the party with spying, never came across it in any fashion and doubted the existence of such an association. I had been an active communist for nearly thirty years and left early in 1958 for reasons I’ve amply described elsewhere.

Radosh pressed me with a hypothetical question: supposing a party member should become a spy, would he drop out of the party? Having established that I had never heard of any association between the party and spying, I responded idly that I would assume so. Note that this bit of abstract speculation, unrelated to any knowledge or experience, is translated by Radosh into a statement of party policy on spying. It thus infers that I knew of such spying, and that I was aware that the party had such knowledge, when I told him unequivocally that I did not.

Since I also told Radosh, as he acknowledges, that I knew nothing of the Rosenbergs, he proceeded to fashion a general principle of party behavior: “Party leaders were generally aware of the existence of these illegal activities and sometimes condoned them at a distance but looked the other way when it came to the specifics.” No evidence is needed, of course, for such glib generalizations, in which Radosh indulges freely. And again, it contradicts directly what I told him of my own experience.

In further speculative chit-chat during our 1978 phone conversation, Radosh and I agreed that the Soviet Union no doubt recruited spies among non-communists and that during World War II, when the USSR bore the brunt of the fighting against Nazi Germany, a dedicated Soviet sympathizer in the party might conceivably have been moved to offer his services.

Plainly, this is not the stuff of historical evidence; my 1978 speculations about hypothetical situations in the 1940s were no more informed or related to fact than those of anyone who had never had a party association. Yet in his book, Radosh uses my past association to invest these speculations with a spurious authority in order to prop up his case against the Rosenbergs.

His burden is a heavy one. By his distortions he charges me with lending credence to what I’ve always considered a large witch-hunting canard about the Communists and Soviet spying. The dramatic propagation of this canard was, I believe, a major cold war motive for the Rosenberg case and the death penalty. I can only speculate about Radosh’s motive in so distorting my words to the same end today.

Max Gordon

New York City

To the Editors:

In his riposte to the Schneirs’ rebuttal in these pages, Ronald Radosh tries to explain away his illegitimate and suspicious footnoting system in The Rosenberg File by asserting that he was denied access to the Meeropol copy of the FBI files on the Rosenberg case by the Fund for Open Information and Accountability, Inc. (FOIA, Inc.) and was forced to use the documents in the FBI Reading Room in Washington, D.C.

The denied access part of this tale is true but requires some explanation. The suggestion that this denial has any bearing on footnoting is utterly false. The documents are the same whichever copy is consulted. The FBI’s numbering system was devised by the FBI and is affixed to each document by them. Scholars who are prepared to submit their work to the scrutiny of competent professionals cite these serial numbers. Those who don’t invite the conclusion that they want to make source checking as difficult as possible.

As to the matter of access to the Meeropol copy of the FBI files on the Rosenberg case, it is true that after they had been given access to the files for a few weeks during the summer of 1978, FOIA, Inc.’s Research Director denied them further access for the following reason.

Advertisement

During that summer, shipments of FBI field office files on ninety-one individuals were arriving every few days in the tiny one-room office of our fledgling organization. Part of the volunteer research team was working pellmell to get each shipment inspected, inventoried, and shelved. Other volunteers were analyzing the files for purposes of the ongoing FOIA lawsuit. Within the limitations of these two critical pieces of work for which the Research Director was responsible, we tried to accommodate requests from the media and academia.

We explained to all those who requested to use the files, however, (1) that until the lawsuit was over, the Meeropols’ attorneys had first claim and primary use of the documents; (2) that FOIA, Inc. did not possess the documents, but merely organized research on them to serve the needs of the lawsuit (in fact, since 1980 all of the documents have been housed in the lawyer’s office); (3) that FOIA, Inc. was not a public library and the documents were not processed and prepared for use by the public, although we hoped to serve this function once the lawsuit was over; and (4) that in practical terms, our physical space was so small that extended use by outsiders impeded the primary task of research for the lawsuit and other work of FOIA, Inc.

Because of these realistic constraints, our policy was to grant access to projects that were short and well-defined so that our own work could go on unimpeded. Those with longer, more diffuse research interests we regretfully referred to the FBI Reading Room.

Of the dozen or so journalists and researchers who used our files in those early days, only two violated the necessary ground rules and were asked to leave. In Radosh’s own terms, one was pro-Rosenbergs, the other was Radosh and his then-collaborator, Saul Stern.

Radosh and Stern were asked to leave because their initial request for two or three days’ use of the files turned into two or three weeks with no end in sight. In short, FOIA, Inc. was not at that time able to accommodate long-term research projects such as theirs, and thus they were asked to leave.

Readers may be interested in the Fall double issue of FOIA, Inc.’s Our Right To Know, which is devoted to analysis by various researchers of the Radosh/Milton book, and the FBI case against the Rosenberg….

Dr. Ann Mari Buitrago

Dr. Gerald Markowitz

On behalf of the FOIA, Inc.

Executive Committee

New York City

Ronald Radosh replies:

Max Gordon’s letter fits a pattern described accurately by Victor Navasky, who pointed out that “it is not uncommon for a subject to disown even the most accurate verbatim reportage once he sees what he said in cold print, especially when it is used in a way which compromises or embarrasses a cause or a friend.”1

Such, I am afraid, is precisely Max Gordon’s response to seeing his own words in print. When I spoke with Gordon on July 10, 1978, I told him I was calling for the purpose of gathering material for a published interview—that his words turned up eventually in a book rather than in an article does not seem relevant. Moreover, I took accurate and verbatim notes—to be careful that nothing he said would turn up in a distorted form.

Sadly, Gordon does not seem to have the courage of his true convictions—of owning up to what he told me during that interview. He now writes: “I replied that I knew nothing of the Rosenbergs and had not heard of them before their arrest in 1950,” and later, that I supposedly acknowledge “that [he] knew nothing of the Rosenbergs.”

What we acknowledged, and wrote in our book, was that “Gordon told us that he had no specific knowledge of whether the Rosenbergs had ever been engaged in espionage but that their abrupt departure from the Party ranks was consistent with this interpretation” (p. 56). But Gordon also told me—and we left this out of our book—the following:

We knew that the Rosenbergs had for some time not been active in the Party. Now, what that was due to we had no way of knowing. There are people we knew who had gone underground for various reasons… There was no way of telling why they had become inactive. That they had become inactive, that we knew. There was some discussion of the fact that they had not been active in the Party for some time.

And later on in the same conversation, Gordon added: “The discussions at that time were along those lines; a lot of people knew it, because we talked about it. It was no secret that [the Rosenbergs] had dropped out of activity some years earlier.” And Gordon stressed that “anyone who became a spy for the Soviet Union was completely separated from the Party”; and he acknowledged that the Soviets may well have “recruited some Party people too,” particularly someone involved in electronics who “might have felt he was useful in that regard.”

Advertisement

It is Gordon, not us, who says this is a statement about “party policy on spying.” Frankly, I wonder why the concept gives Gordon so much of a problem. In his classic study of American Communism, the late Joseph Starobin wrote that “some Americans who called themselves Communists were…involved in this form of service [espionage] to the Soviet Union.”2 Why can’t Gordon acknowledge this as well?

As for those noble souls at FOIA, Inc., their own pamphlet heralded as an “answer” to The Rosenberg File informs its audience that Joyce Milton and I are “apologizing for anti-Semitism” and that we are defenders of “the government, the FBI, and the capitalist class.” And one of their authors, who dubs our book “The Fraud of the Century,” proclaims in print that our book “has all the earmarks and objective consequences of an FBI Cointelpro operation.”3 One has to pause before believing one word from these people about why they refused Sol Stern and me permission to use their files in 1978. Unfortunately for them, in a fit of anger, their founder and counsel, Marshall Perlin, boasted to Curt Suplee of The Washington Post (Sept. 10, 1983), “I kicked them out,” and came forth with a reason: “Before even looking at the files, they had already come to a conclusion.” In fact we had not, but Perlin clearly disapproved when we found indications of espionage during our two weeks of work on the files. Perlin’s act, we must note, violated the tax exempt statute of FOIA, Inc., which stresses that its repository of files are open to all working scholars and journalists—not only those who agree with the views of its board of directors.

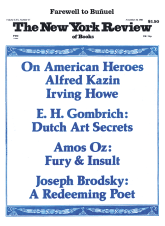

This Issue

November 10, 1983

-

1

Victor Navasky, “Weinstein, Hiss and the Transformation of Historical Ambiguity into Cold War Verity,” in Beyond the Hiss Case, Athan Theoharis, ed. (Temple University Press, 1982), p. 222. ↩

-

2

Joseph Starobin, American Communism in Crisis, 1943-1957 (Harvard University Press, 1972), p. 312. ↩

-

3

FOIA, Inc., Our Right to Know, “Special Issue—the Rosenberg Controversy Thirty Years Later.” See especially: Norman Markowitz, “The Witch-Hunter’s ‘Truth,”‘ p. 11, and Ann Mari Buitrago, “The Fraud of the Century,” p. 18. ↩