In his introduction to Soul Murder, Dr. Shengold confesses that he is “fond of meandering designs; this book proceeds more by association than by orderly progression.” In his acknowledgements he states that in his present book, Soul Murder, and in his previous book, Halo in the Sky (1988), he has “published most of the ideas and discoveries that have been derived from my practice of psychoanalysis over the past thirty years,” and elsewhere that unspecified portions of this book have already appeared as articles in four different psychoanalytic journals.

Dr. Shengold is a distinguished psychoanalyst—he is clinical professor of psychiatry at the New York University School of Medicine—who, after being in practice for over thirty years, has now collected some of the various papers he has written and woven them into the semblance of a book, as opposed to a volume of collected papers. However, despite the patchwork, the repetitiousness, and the “meandering design,” his book does have a recurrent theme, and this theme is vividly described by its title, Soul Murder.

“Soul Murder,” writes Shengold,

is my dramatic designation for a certain category of traumatic experience: instances of repetitive and chronic overstimulation, alternating with emotional deprivation, that are deliberately brought about by another individual. The term does not define a clinical entity; it applies more to pathogenic circumstances than to specific effects.

The term was first used by Anselm von Feuerbach in 1832 to describe the case of Kaspar Hauser, the seventeen-year-old boy who, locked alone in a cellar since early childhood, had “gradually regressed into a kind of obsessive-compulsive automaton.” But it was Paul Schreber’s autobiography, written in 1902 and later the subject of one of Freud’s most famous case histories, that entrenched the expression in the psychoanalytic vocabulary and supplied some of its most powerful illustrations. Shengold draws on these and many other earlier studies of soul murder, as well as numerous instances from literature and history of people devastated by the persecutions of an impersonal and merciless authoritarian force, in reflecting on the cases of abuse he has studied over the years and their implications for psychoanalysis.

In spite of the undeniable power of this testimony, however, there are objections to be raised to the imprecision of his use of the term soul murder. Although the concept is a vivid metaphor for describing the actions of persons who deliberately abuse, batter, deprive, torment, torture, and brainwash helpless victims, often children, it is nonetheless misleading in certain respects. Actual murder leaves the victim dead, with no possibility of living or reviving to tell the tale, while the victims of what Shengold calls soul murder are still alive and may under certain circumstances or psychological constellations be able to tell the tale, thereby regaining the spirit which their “murderers” sought to crush and recover the sense of identity and personal autonomy of which their “murderers” sought to deprive them.

Some creative artists are striking examples of survivors who live to tell the tale. Shengold describes Kipling, Chekhov, Dostoevsky, and Orwell as victims of soul murder, and creates confusion—for himself and even more for his readers—by trying to explain how traumatic experience “can contribute to the strengths and talents of the suffering victim.” Part of this confusion arises, it seems to me, because he oscillates between the idea that a person either has or has not been soul-murdered, in which case he either is or is not psychically dead—which is what the murder metaphor implies—and his recognition that psychical damage, traumatic experiences, vary in their intensity from slight to extreme.

In spite of the central metaphor of murder, Shengold’s book acknowledges various degrees of emotional abuse; he identifies two characteristics that seek to distinguish soul murder from less radical forms of psychic destruction. First, unlike “normal neurotic” behavior (Shengold insists that everyone who is not psychotic is to some degree neurotic), the soul murderer’s treatment of his victims reaches such extremes of coldness and brutality that he or she no longer seems capable of empathy, or recognizing the unique humanity of the victim. Second, the reaction of the victim involves the use of such an impressive array of defenses1 that the pain he or she has suffered seems to have been obliterated, but only at the price of the loss of his freedom of emotional expression. Kaspar Hauser, for example, appeared to be completely asexual and incapable of feeling anger against his captor, whom he simply called “the Man who was always there.” Shengold writes, “It was as if some instinctual energy had been extinguished.”

The idea that there are degrees of soul murder is expressed clearly at the beginning of Shengold’s chapter on Kipling, where he writes: “Soul murder can be overwhelmingly or minimally effected; it can be partial, diluted, chronic, or subtle.”2 Just how one is to estimate the different degrees of soul murder, however, remains puzzling throughout Shengold’s book. “Kipling’s case,” for example, “involves his desertion by good parents and their replacement by bad, persecutory guardians.” But after reading this chapter more than once I am uncertain whether Shengold really believes that Kipling’s parents were as “good” as Kipling himself thought they were or the guardians as “bad” as Kipling described them in his fiction; or whether he thinks that Kipling was a great writer despite his childhood experience of abuse and deprivation or as a result of it. But this chapter does give Shengold the opportunity to give quotations from Kipling that describe with poetic clarity and intensity the predicament and the emotional scarring of the kind of patient who has been Shengold’s abiding preoccupation. For instance:

Advertisement

When young lips have drunk deep of the bitter waters of Hate, Suspicion, and Despair, all the Love in the world will not wholly take away that knowledge; though it may turn darkened eyes for a while to the light, and teach Faith where no Faith was.3

He also quotes the poem “The Mother’s Son” (1928), which describes a patient in an asylum looking at his reflection in a mirror.

And it was not disease or crime

Which got him landed there,

But because They laid on My Mother’s Son

More than a man could bear.

Shengold’s text reads “than any man could bear” and one of the interpretations he offers of this poem, viz. that the beardedness of the face in the mirror shocks the viewer because he had expected or hoped to see his childhood hairless face, is invalidated by one of the verses which he does not quote:

They pushed him into a Mental Home

And that is like the grave;

For they do not let you sleep upstairs

And you aren’t allowed to shave.

Some of the complexities and tortuousness of Shengold’s accounts of soul murder in the lives of writers arise from the fact that he both has and has not accepted Freud’s reluctant admission that “Before the problem of the creative artist analysis must, alas, lay down its arms.” He quotes it with approval, but incompletely and in a garbled way; a few pages later he can write,

In some still unanalyzable way Chekhov can transcend and transform his neurosis—at least in his art. We are confronting a magnificent psychological gift and talent, not pathology; this is terra incognita for the psychoanalyst; another Freud is needed.

And of Dickens he writes:

If one had the facts, however, one might find his talents and strengths as well as his subject matter linked genetically to his early, traumatic experiences.

At other points, as in the case of Kipling, he seems to suggest such links himself without being precise about what they are. When one remembers that Soul Murder is based on papers written for psychoanalytical journals and that some of them must also have been read to audiences of psychoanalysts, one is forced to believe that the spirit of Freud’s original analytical imperialism is alive and well in American psychoanalytic circles.

A contributing factor to Shengold’s obscurity is one which will, I suspect, baffle all readers who have not at some time immersed themselves in the history and politics of the psychoanalytic movement. In writing about child abuse and soul murder he has entered a theoretical controversy about the relative importance of fantasy and experience in the genesis of neurosis. In 1984, Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson published his The Assault on Truth: Freud’s Suppression of the Seduction Theory, in which he argued that Freud had been right when he asserted, as he had in “The Aetiology of Hysteria” (1896), that all neurotics have been abused sexually in their childhood, and he had been dishonest in abandoning this idea in favor of the socially innocuous one that children regularly have Oedipal fantasies of sexual contact with their parents. By writing this book Masson was asserting both specifically that, since neurosis is common, sexual abuse of children must also be common and, generally, that neuroses are the result of real events in childhood, and not of fantasies created in childhood as most orthodox, mainstream analysts seemed to believe.

According to Janet Malcolm’s In the Freud Archives (1984) Shengold was initially highly impressed by Masson and had even got up at a meeting Masson had been addressing to say, apparently seriously, “I’ve never heard of this man, but he’s a find. Canada has sent us a national treasure.” But as he got to know him better he became disenchanted. So although Shengold clearly believes that child abuse and soul murder are not uncommon, he is at pains to make it clear that he does not agree with Masson’s thesis that child abuse is ubiquitous or his denial of the pathogenic power of fantasy. Shengold also disassociates himself from the psychoanalyst Robert Fliess,4 by whom he has evidently been much influenced theoretically but who also believed that all his patients had been seduced in childhood and that most of their parents had been ambulant psychotics. “How frequent are the seduction and abuse of children?” Dr. Shengold asks.

Advertisement

They are certainly more common than had been realized for decades. Now that people are increasingly aware of the fact of child abuse, accounts fill our newspapers, magazines, and even television (as well as the psychiatric literature). It makes no sense to me that all neurotics (and this means everyone) have been traumatically abused and seduced in their childhood, as Freud first assumed and as Fliess and Masson assert. Soul murder has certainly not happened to everyone, but this book is evidence of my conviction that overt, substantial parental seduction and deprivation are frequent.

Although Shengold states clearly and courteously the extent of both his indebtedness to, and disagreement with, Jeffrey Masson and Robert Fliess, the same cannot be said of his attitude toward Morton Schatzman, the American psychotherapist working in London who in 1973 published Soul Murder: Persecution in the Family.

In this book Schatzman suggested that the delusions of persecution by God described by Paul Schreber in his Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (1903), which Freud in a famous paper5 had interpreted as the result of Schreber’s passive homosexual love for his father, were better interpreted as replicas and transformations of physical assaults that his father had inflicted upon him in childhood; and that his father, Moritz Schreber, far from being an admirable person “by no means unsuitable for transfiguration into a God in the affectionate memory of the son,” as Freud had described him, had been a sadistic tyrant.

This book engendered considerable controversy, with Schatzman on the one hand arguing that Schreber’s delusions of persecution were the direct result of maltreatment and abuse by his sadistic father and the orthodox analysts on the other hand defending Freud’s original thesis that delusions of persecutions are vicissitudes of passive homosexual drives. It would seem however that both parties to this controversy have been both ignorant and misguided. According to Han Israëls, the Dutch sociologist whose historical study of the Schreber family has just been translated into English (Schreber: Father and Son, 1989), Moritz Schreber was not as famous and influential as both Schatzman and Freud had assumed, was not such a paragon as Freud had assumed or as vicious as Schatzman painted him, and neither Freud’s nor Schatzman’s aetiological theories stand up to critical scrutiny.

However, despite the fact that it was Schatzman who first raised the issue of soul murder and started the controversy in which Shengold himself took part, Schatzman’s Soul Murder is not mentioned anywhere in the text of Shengold’s Soul Murder—though it is included in the bibliography.

Shengold’s reason for ignoring someone with whose work he must be familiar and the title of whose book he has borrowed must, I think, be the fact that Schatzman is an outsider, not a psychoanalyst, and, therefore, not a member of that elect group, the American (or should it be the New York?) psychoanalytic establishment, which probably makes up a large part of Shengold’s audience.

According to Janet Malcolm,

Shengold occupies a special corner in the analytic avant-garde. On the one hand, he shares the avant-garde’s concern for “people who have been unloved, ill-used and deprived,”…but on the other he does not share its (variously expressed) need to meddle with orthodox theory and practice. Almost alone among analysts who have dedicated themselves to the repair of seriously damaged souls, Shengold has remained comfortable with regular Freudian psychoanalysis.

Further, although Shengold undoubtedly is concerned with the unloved, ill-used and deprived, the clinical cases on which Soul Murder is based are not of the most extreme type. “My material,” he writes,

will seem mild indeed to those dealing with battered and sexually assaulted children who turn up in police stations and hospital emergency rooms. I will describe people who were assaulted as children and have been scarred, but who have enough ego strength to maintain their psychological development and have summoned the considerable mental strength needed to present themselves as patients for psychoanalysis…. I have not studied any of the countless number who have ended as derelicts, in madhouses, or in jails, or those who have not even survived an abused childhood.

However, the material is dramatic enough. Of the seventeen patients—twelve men and five women—Shengold discusses in some detail, twelve had been abused in childhood by their mothers, and three by their fathers. As for the other two, one was a woman who had been seduced at the age of five by a man who was not her father, and the other was a man who had been grossly neglected by both parents but not abused. Although the sample is not large enough to be statistically significant, Shengold’s findings nonetheless suggest that the popular idea that child abuse is essentially a matter of fathers abusing their daughters is something of a myth. Both sons and daughters can, it seems, be sexually abused by their mothers; the kinds of maternal abuse mentioned by Shengold include genital exhibitionism, fellatio, and anal rape masquerading as therapeutic administration of enemas.

The only incestuous relationship described by Shengold is between a mother and her adolescent son after he reached puberty; it was initiated by the mother, enjoyed by the son, but terminated by the mother after a few weeks when the son had his first ejaculation. One of the effects this brief encounter had on the son was “guilt-ridden arrogance.” In later life his wife was often provoked into saying to him, “You know, you are not of royal birth.” Not surprisingly, Shengold’s discussion of this case includes allusions to Oedipus Rex.

In addition to describing the soul murders partially inflicted on four writers and eighteen patients, Shengold also discusses a variety of related topics: the rat, both as an actual animal, which under stress kills and eats its own kind, and as an apt and much used symbol of projected oral aggression; teeth in folklore and as a symbol of cannibalistic impulses and castration anxiety; the sphinx as a symbol of what I would call a combined parent figure but which Shengold calls “the primal parent”; the Schreber case; Kaspar Hauser; autohypnosis; quasi-delusions occurring in the normal (“we neurotics all have them!”); and many others. Unfortunately, the combination of Shengold’s wish to record everything he has discovered in thirty years of analytical practice and his affection for “meandering designs” often make him hard to follow; his erudition is impressive, but also overwhelming and distracting.

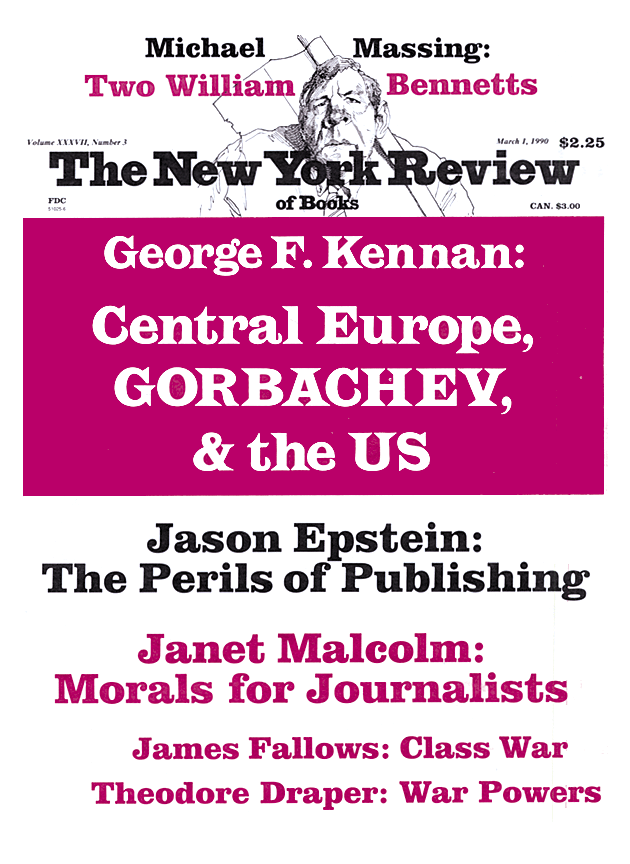

This Issue

March 1, 1990

-

1

Shengold cites such defenses as “an extraordinary power of disassociation from feeling and experience; autohypnotic states; compromised identity, with vertical ego splitting allowing for phenomena analogous to the doublethink and crimestop of Orwell’s 1984; a paranoid potentiality (if you can’t trust your parents, whom can you trust?); superego defenses with simultaneous overpermissiveness and a strong unconscious need for punishment .” ↩

-

2

Surely this sentence should read: “Soul murder can be either overwhelming or slight; it can be partial or complete, diluted or concentrated, chronic or acute, subtle or crude.” ↩

-

3

Curiously enough this passage from Kipling’s story “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep” is misquoted by Shengold, who gives “your” for “young.” ↩

-

4

Uninformed readers are warned that two Fliesses, Wilhelm and Robert, father and son, Berlin nasal surgeon and New York psychoanalyst, friend and correspondent of Freud and elder colleague of Shengold, feature in this book, but they are distinguished in neither the text nor the index. Shengold presumably assumed that his analyst readers would recognize immediately which Fliess he was referring to, while the indexer can have had no reason to suppose that there were two of them. ↩

-

5

“Psycho-analytic notes on an autobiographical account of a case of paranoia (dementia paranoides),” 1911. ↩